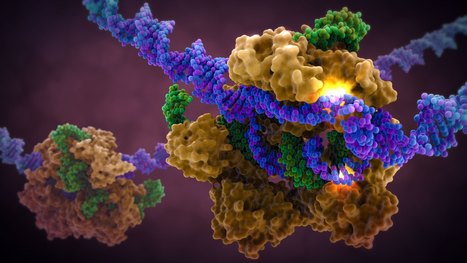

A landmark study published in Cell has shown that prime editing, a cutting-edge form of gene editing, can correct mutations causing Alternating Hemiplegia of Childhood (AHC) with a single in-brain injection. The research team fixed the most prevalent ATP1A3 gene mutations in mouse models, reducing symptoms and more than doubling survival, a first-of-its-kind success in treating a neurological disease directly in the brain. CRISPR-based gene editing was delivered through an harmless adeno-associated virus called AAV9. In parallel, patient-derived cells (iPSCs) responded similarly, reinforcing the method’s promise for human translation. Importantly, this success opens the door to targeting other genetic brain disorders previously deemed untreatable. Although results are preliminary, this study provides robust proof‑of‑concept for personalized gene editing in the brain and opens doors toward potential treatments for other intractable genetic neurological disorders.

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

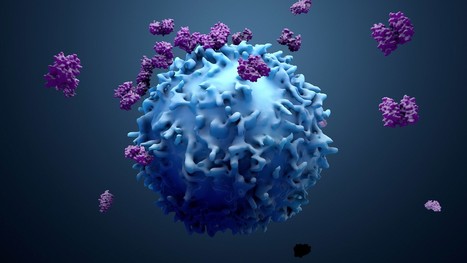

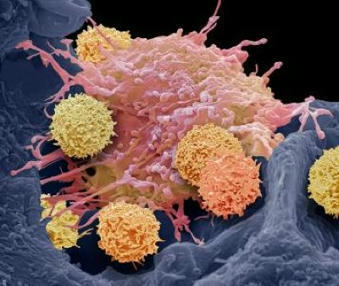

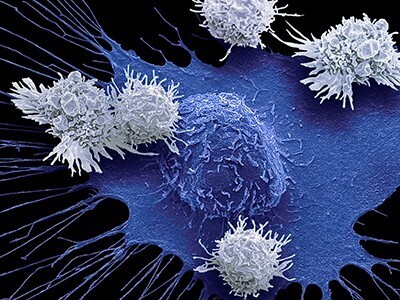

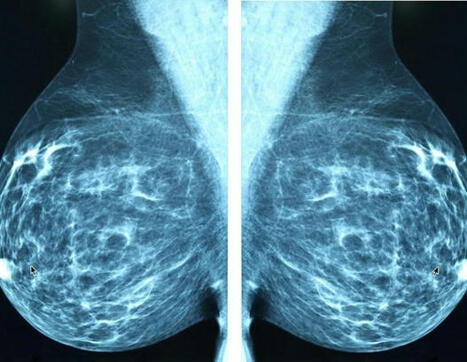

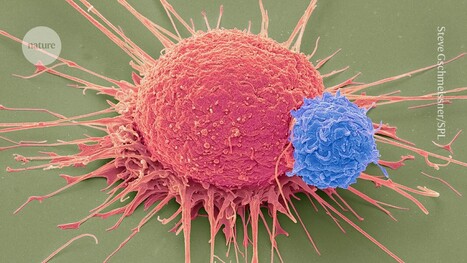

Following the approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), doctors at the University of Washington's Siteman Cancer Center will administer tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy to treat certain adult patients with metastatic melanoma, an aggressive skin cancer that has spread to other areas of the body. The treatment is intended for patients with metastatic melanoma that cannot be treated by surgery and has continued to grow and spread despite having already been heavily treated with other approved strategies, including chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors. The first centers to administer TIL therapy are those with extensive expertise in treating patients with cellular immunotherapies, such as CAR-T cell therapy for blood cancers. For the therapy, doctors at an approved treatment center take a sample of the tumor and send the tissue to an Iovance manufacturing facility, where tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are isolated from the tumor and then expanded outside the body. This TIL therapy cell product is then cryopreserved and returned to the patient. When returned to the patient's body via intravenous infusion, the tumor-specific T cells, now numbering in the billions, are much more effective at killing tumor cells throughout the body.