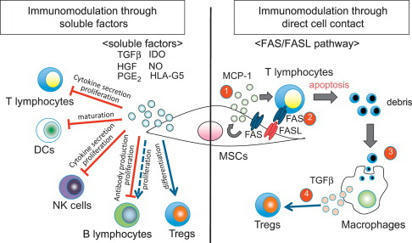

T Cell Proliferation T cell proliferation leads to formation of millions of T cells expressing specific cell membrane TCRs, capable of binding the most diverse antigens, including self-antigens. From: Epigenetic Principles of Evolution (Second Edition), 2019 Related terms: View all Topics Stem Cell-Based Approach to Immunomodulation Kathryn J. Wood, ... Ou Li, in Regenerative Medicine Applications in Organ Transplantation, 2014 61.3.4 Modulation of T-Cell Responses in Rejection by MSCs T-cell proliferation and activation are prerequisites for allograft rejection [2,85]. A large body of data demonstrate that MSCs can modulate T-cell proliferation, activation, and function both in vitro and in vivo[28,44,86–89]. Moreover, the capacity for MSCs to inhibit Th17 cell differentiation [90,91] or to shift the T-helper cell balance in favor of a more anti-inflammatory phenotype has been demonstrated in vitro [92–96]. The mechanisms utilized by MSCs in mediating these effects vary between in vitro and in vivo models. However, the secretion of soluble factors by MSCs is a common feature (English, 2012). IDO and PGE-2 have been implicated in MSC inhibition of Th17 differentiation [90,91]. In the case of PGE-2, the steps involved in the process require contact-dependent COX-2 induction of PGE-2 and direct inhibition through EP4 [90]. MSCs can also mediate this effect through suppressing the Th17 transcription factor RORγt and upregulating Foxp3 to induce a Treg phenotype producing IL-10 [96]. MSC-derived TGF-β has been shown to play a partial role in shifting the balance of Th1/Th2/Th17 and Treg in an autoimmune disease model [31]. A role for matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)2 and MMP9 secreted by MSCs facilitating cleavage of CD25 expressed on CD4+ T cells thereby inhibiting alloantigen driven proliferation and so preventing islet allograft rejection has also been described [44]. Other evidence suggests that MSC-derived MMPs also cleave CCL2 which subsequently inhibits Th17 activation via a STAT3-dependent pathway [97]. MSCs also have the capacity to expand or induce Treg in the setting of an alloimmune response [43,45,98,99] and in some cases can generate a state of Treg-dependent tolerance [30,45]. Both of these studies elegantly demonstrate the importance of Treg in MSC-induced tolerance using Treg depletion strategies with IDO potentially playing a significant role [30]. In vitro, MSC induction of Treg is thought to involve cell contact, PGE-2, and TGF-β [94]. In vivo, MSC-derived TGF-β was required for the generation of antigen-specific Treg and overall, TGF-β seems to be the major soluble factor involved in MSC promotion of Treg in vivo [29,31,100,101]. T-Cell Activation and Tolerance Erik J. Peterson, Jonathan S. Maltzman, in Clinical Immunology (Fifth Edition), 2019 Coreceptors Transduce Signals That Are Integrated With TCR Signals T-cell proliferation and the initiation of effector function require that the T cell must receive signals in addition to the TCR via other cell surface receptors.18 This requirement for multiple signals allows the T cell to be extremely sensitive to TCR binding while protecting against the inappropriate activation of potentially dangerous effector cells. Because T cells respond to antigens presented on APCs, stimulation under physiological conditions involves the potential engagement of multiple coreceptors on the T cell by cognate ligands on the APCs. Some coreceptors may function to increase the avidity of T cells for interacting APCs. However, many coreceptors exhibit intrinsic signal-transducing capacity. Some signal independently of the TCR; others intersect with TCR-driven signaling machinery. Additionally, coreceptors may function as recruiters of cytoplasmic signaling molecules, including adaptor proteins, as described above. The most intensively studied coreceptors are CD4 and CD8 (Chapter 4). CD4 or CD8 expression on peripheral T cells define subsets that respond to MHC class II- or class I-bound peptide antigens, respectively (Chapter 6). Either CD4 or CD8 can contribute to enhanced TCR signal strength because they each associate with LCK.19 This constitutive interaction, which occurs via specific residues within the CD4 and CD8 cytoplasmic domains, localizes a key effector enzyme to the TCR complex. Cytokines in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Kate A. Markey, Geoffrey R. Hill, in Cytokine Effector Functions in Tissues, 2017 IL-6 IL-6 promotes T cell proliferation, the differentiation of cytotoxic T lymphocyte populations, and, when present in combination with TGF-β, promotes Th-17 development.65,66 Preclinical studies of IL-6 in GVHD and GVL confirm its key role as a pathogenic cytokine in GVHD. The absence of IL-6 in the donor T cell pool (using IL-6 deficient donor mice) or systemic blockade of IL-6 with an anti-IL-6R antibody results in decreased aGVHD with no loss of GVL effects in the models used.9,67 Recent data demonstrate that IL-6 is the major cytokine detectable in patient plasma early after BMT and that it appears to play a dominant role in conditioning-related pathology.68 Blockade of IL-6 with tocilizumab (soluble IL-6R) has now progressed through a successful phase I/II clinical trial with low levels of acute GVHD in comparison to historical controls.68 This represents a promising new strategy for GVHD prevention. Macrophages Galen B. Toews, in Asthma and COPD (Second Edition), 2009 Macrophages and Initiation of Antigen-specific T2 Immune Responses in Asthma Resident pulmonary AMs actively suppress T-cell proliferation induced by antigen or polyclonal stimuli [73]. Changes occur within the local inductive milieu of the lung in patients with asthma. AM suppression is reduced after exposure to allergens [106–108]. The tissue microenvironment is a crucial regulator of specific immune response generation (Fig. 11.1). The presence of IgE on APCs likely promotes the uptake and the processing of allergens and their eventual presentation to naïve T-cells. DCs express both FcεR I and FcεR II. These two receptors could function to capture allergen bound to allergen-specific IgE and thus focus the immune response through facilitated antigen presentation [109]. Antigens also deliver signals via quantitative variation in ligand density on APC. Peptide/MHC class II complexes that interact strongly with the TCR favor T1 responses, whereas weak interactions result in the priming of T2 responses. The overall binding affinity can be varied by modifying the peptide, which results in different signals. The mechanisms by which signals delivered via the TCR control differentiation is uncertain; differential TCR aggregation may result in differential intracellular signals that favor distinct cytokine gene expression or certain MHC–TCR interactions may favor differential co-receptor expression [110]. As noted above, co-stimulatory molecules may direct the polarization of T-cells into T1 or T2 cells; B7.2 provides only a moderate signal for T2 cell differentiation; and co-stimulatory signals may be delivered either by the APC that presents the antigen or by the bystander APC. Thus, macrophages may serve as bystander APC and influence DC-induced T-cell proliferation [111]. Soluble cytokines produced by cells of the innate immune response are likely the major regulators of T-cell differentiation (see “Innate Control of Adaptive Immune Responses” section). Immunotherapy in Transplantation Kentaro Akiyama, ... Takuo Kuboki, in Stem Cell Biology and Tissue Engineering in Dental Sciences, 2015 61.2.1.1 Interaction with T-Lymphocytes MSCs are known to inhibit T-cell proliferation by arresting the cell cycle in the G1/G0 phase and down-regulating cyclin D2 expression [6]. As part of the mechanisms involved in this process, MSCs produce a large number of soluble factors that work as anti-inflammatory agents. Di Nicola M et al. reported that human bone marrow MSCs inhibit both CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocyte proliferation by secreting transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFβ1), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in vitro [7]. Another study showed that MSCs inhibit stimulated lymphocyte proliferation and mitogenic response independently of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) [8]. MSCs also produce indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), which accelerates tryptophan degradation and kynureine synthesis resulting in inhibition of T-lymphocyte proliferation [9]. Nitric oxide (NO) is another immune regulation factor secreted by MSCs [10,11]. NO inhibits proliferation of T-lymphocytes by suppressing phosphorylation of transcription factor, signal transducer, and activator transcription-5 (STAT-5) [12]. Human leucocyte antigen-G5 (HLA-G5) from MSCs is a trigger for inhibition of T-lymphocyte function, followed by up-regulation of T-helper type 2 (Th2) and regulatory T-cell (Tregs) [13,14]. On the other hand, MSCs are able to inhibit T-lymphocyte proliferation by direct cell-to-cell contact [15–17]. Krampera et al. reported that MSCs physically hinder T-lymphocytes from contacting antigen presenting cells in a non-cognate fashion [18]. T-lymphocytes have several subsets. CD8+CTL plays an important role in MHC-dependent allogenic or virus- infected cell depletion. MSCs showed reducing CTL cytotoxicity by inhibiting CTL formation [19]. It has been indicated that the relationship between gamma-delta T-lymphocytes (γδT) and acute graft-vs-host disease (GvHD). MSCs suppress γδT-lymphocyte proliferation without any functional inhibition in vitro (Figure 61.1) [20]. Furthermore, some reports indicated that immunomodulation of MSCs are not only through inhibition of T-lymphocyte proliferation, but also by induction of T-lymphocyte apoptosis. A previous study demonstrated that MSCs secrete IDO, induce 3-Hydroxyanthranilic acid (HAA) synthesis during tryptophan metabolism, and induce cell apoptosis by inhibiting the NFκB pathway in T-lymphocytes [21]. Augello et al. reported that MSCs induce apoptosis of T-lymphocytes by activation of the programmed death 1 pathway [22]. More recently, MSCs have been demonstrated to induce T-lymphocyte apoptosis through the FAS/FAS ligand (FASL) pathway, and consequently lead to immunotolerance (Figure 61.1) [23]. Neuropeptides for Mucosal Immunity David W. Pascual, Kenneth L. Bost, in Mucosal Immunology (Third Edition), 2005 Tachykinins and VIP as costimulation factors for T lymphocytes Early studies showed that SP supports T-cell proliferation (Payan et al., 1983; Stanisz et al., 1986), suggesting that T lymphocytes can express NK1-R. In support of this possibility, recent investigations by several laboratories have demonstrated in vitro and in vivo expression of NK1-R by T lymphocytes. NK1-R mRNA expression by cultured murine (McCormack et al., 1996) and human T cells (Li et al., 2000) or T-cell lines has been reported. In addition, the functionality of NK1-R expression by T lymphocytes has been demonstrated in co-cultures with SP-producing dendritic cells (Lambrecht et al., 1999). It is interesting that NK1-R mRNA expression was observed in intraepithelial and lamina propria T lymphocytes but not in splenic T cells (Qian et al., 2001a). During the host response against respiratory syncytial virus, NK1-R expression was markedly increased in CD4+ T lymphocytes (Tripp et al., 2002). However, the most compelling evidence to date for the importance of NK1-R expression on T lymphocytes comes from studies by Weinstock and colleagues, using a murine model of schistosomiasis. Using NK1-R−/– mice, they observed significant reductions in the size of schistosome-induced granulomas in comparison with disease in wild-type mice (Blum et al., 1999). The limited IFN-γ production by infected NK1-R−/– mice suggested that T cells may be an important target for SP during schistosomiasis. Additional studies clearly demonstrated that the presence of NK1-R on T lymphocytes was largely responsible for schistosome antigen–induced IFN-γ production (Blum et al., 2003). Mechanistic studies demonstrated that schistosome antigen, as well as IL-12, could induce expression of NK1-R during murine schistosomiasis (Blum et al., 2001). Collectively, these studies clearly demonstrate the importance of NK1-R expression and activity during the host response to a parasitic infection. To further address the role of SP contribution to S-IgA responses, NK1-R−/– mice were orally immunized with an attenuated Salmonella construct expressing colonization factor antigen I (CFA/I). This vaccine construct has been shown to elicit a biphasic Th cell response (Pascual et al., 1999) supported by early robust IL-4- and IL-5-producing CD4+ T cells. When such a construct was used to orally immunize NK1-R−/– mice, a significant increase in antigen-specific S-IgA antibody titers was obtained (Trunkle et al., 2003). Surprisingly, no significant differences in IFN-γ production were observed between NK1-R/+/+ and NK1-R−/– mice, but increased production to IL-6 was obtained. This evidence suggests, minimally, that some intracellular infections are resolvable in the absence of NK1-R function, perhaps via increases in S-IgA antibody responses. VIP-containing nerve fibers also extend into the T-cell regions of the Peyer's patches (Ottaway et al., 1987) to affect the CD4+ T cells, whereby stimulation of CD4+ T cells by SP or VIP can affect Ig synthesis. While SP has been shown to exert stimulatory effects upon T cells, VIP has the opposite effect and will inhibit mitogen-induced T-cell proliferation (Stanisz et al., 1986; Ottaway and Greenberg, 1984). This effect apparently occurs through a reduction of IL-2 synthesis (Ottaway, 1987; Metawali et al., 1993) and an inhibition of IL-4 in anti-CD3-stimulated T cells incubated with VIP (Wang et al., 1996). These early studies suggested that VIP exhibited anti-inflammatory properties, but this was not confirmed until recently. As stated earlier, VPAC1 is constitutively expressed, whereas VPAC2 is inducible when T cells are stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody (Delgado et al., 1996). Upon stimulation, VPAC1 levels decrease, while VPAC2 levels are induced. This evidence suggests that VIP action on CD4+ T cells is via the effect of VPAC2 acting specifically upon Th2 cells. To begin to address the regulation of VPAC1 and VPAC2, a mouse deficient in VPAC2 was derived and exhibited enhanced delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) responses supported by increased IFN-γ production (Goetzl et al., 2001). To exacerbate Th2 cell function, a transgenic mouse was derived in which CD4+ T cells express the human VPAC2 (Voice et al., 2001). These mice showed increased serum IgE and IgG1 but not IgA antibodies. This Th2 cell bias was evidenced as enhanced susceptibility to TNP-induced cutaneous anaphylaxis and depressed DTH responses. Studies have yet to determine whether VPAC1 and VPAC2 are regulated in a similar fashion by Peyer's patch Th cells, in a manner analogous to that seen with splenic Th cells. Bone Marrow DANIEL A. ARBER, in Modern Surgical Pathology (Second Edition), 2009 T-CELL PROLYMPHOCYTIC LEUKEMIA T-PLL is a clonal T-cell proliferation that occurs most commonly in elderly patients and has a slight male predominance.328,372,373 The disease also occurs frequently in younger patients with ataxia telangiectasia.374 Patients have a markedly elevated white blood cell count as well as organomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Nodular or maculopapular skin lesions are also common. The peripheral blood white blood cell count is usually greater than 100 × 109/L with a predominance of medium-sized cells with abundant basophilic cytoplasm and a single prominent nucleolus (Fig. 43-27). These cells are similar to B-cell prolymphocytes but may have a more convoluted nucleus than in B-PLL. Normocytic anemia and thrombocytopenia are common. The bone marrow may not be involved to the degree that would be expected by the marked elevation in peripheral blood prolymphocytes. The pattern of involvement may be interstitial, diffuse, or mixed and reticulin fibrosis is frequently present (Fig. 43-28).353 In general, T-PLL is an aggressive disease with short survival. However, a subpopulation of patients with T-PLL, including many with ataxia telangiectasia, have an initial, indolent disease course that eventually transforms to the more typical aggressive disease.375 Immunophenotyping is necessary to distinguish T-PLL from B-PLL and is often helpful in excluding acute leukemia. T cell-associated antigens CD2, CD3, CD5, and CD7 are expressed by T-PLL and surface CD3 is present. Most cases are CD4+, but a subset of cases expresses CD8 or both CD4 and CD8. The absence of both CD20 and immunoglobulin light-chain expression excludes B-PLL. The lack of TdT and CD1a expression and the presence of surface CD3 exclude most cases of T-cell ALL. T-cell receptor gene rearrangements are uniformly detectable in T-PLL. Cytogenetic abnormalities in T-PLL include inv(14)(q11q32) and t(14;14)(q11;q32), involving the TCL1 gene in the region of the T-cell receptor α/β locus, iso(8q), trisomy 8, 12p13 deletions, and t(X;14)(q28;q11).375,376 Abnormalities of chromosome region 11q22-23, involving the ATM tumor suppressor gene that is consistently mutated in ataxia telangiectasia are present in some patients with T-PLL even in the absence of ataxia telangiectasia.377 Some T-cell chronic lymphoproliferative disorders have cells with morphologic features similar to those of B-CLL without the prominent nucleolus typical of usual-type PLL.378,379 Cases of this type are considered small cell variants of T-PLL, and the term T-cell CLL should no longer be used. Although the median age and white blood cell count are lower in these patients than in usual-type T-PLL, these cases have immunophenotypic and cytogenetic features similar to those of T-PLL and a similarly aggressive clinical course. Development of T Cell Immunity Jeong M. Kim, in Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, 2010 E Granzyme Dependent Cytotoxicity Treg cell mediated inhibition of in vitro effector T cell proliferation was demonstrated to require cell-to-cell contact. Although the molecular basis for contact-mediated suppression is largely unknown, recent reports have revealed that Tregs also require cellular contact for target cell killing via the granule exocytosis pathway.150,151 Granule-mediated cytoxicity is dependent on granzymes, granule resident proteases, which initiate a cascade of apoptosis-promoting cleavage events. As in effector T cells, granzyme expression is induced in Tregs in response to T cell receptor signaling. While granzyme A is primarily expressed by activated human Tregs,151 granzyme B is the predominant granzyme induced in murine Tregs.150 Granzyme A and B differ in substrate specificity and the kinetics of cell death induction, but activated murine and human Tregs comparably induce effector T cell death at 1:1 ratio of regulatory to effector T cells. In vitro cytotoxicity was dependent on granzyme function, as suppression of effector T cell proliferation was severely compromised in cultures containing granzyme B deficient Tregs.150 Cytolytic granules also contain perforin, which is essential for target cell lysis in CD8+ CTLs and NK cells. The deposited perforin polymerizes on the target cell plasma membrane in a calcium dependent manner and generates holes that were hypothesized to serve as granzyme conduits into the target cell. However, accurate measurements of pores formed by perforin suggest that the diameter of polyperforin channels do not accommodate granzyme passage.152 Although the exact function of perforin remains unknown, phenotypic similarities in mice deficient in either perforin or granzyme B provide evidence that perforin plays a nonredundant role in targeted cytolysis by lymphocytes. In support of this idea, inhibiting perforin by either EDTA or concanamycin A treatment abrogates target cell killing by human Tregs. In contrast to these findings, perforin deficient murine Tregs were equally suppressive as its wild-type counterparts in vitro, suggesting that perforin is not essential for granzyme B dependent target cell lysis in murine Treg cells. These discrepant results may reflect the usage of different granzymes for target cell killing in mouse versus human Tregs. In this regard, granzyme A may be more dependent on perforin for killing that granzyme B. Alternatively, calicium chelators or concanamycin A may not be specific for perforin inhibition, affecting target cell cytolysis independent of perforin function. Human Tregs, additionally, have been demonstrated to kill monocytes, DCs, and activated CD8+ T cells151 (Fig. 3B). Murine Tregs are also capable of killing B cells in vitro.114 Assay for Antigen-Specific T-Cell Proliferation in Mice Şefik Ş. Alkan, in Immunological Methods, 1979 Publisher Summary This chapter discusses the assay for antigen-specific T-cell proliferation in mice. While lymphocyte proliferative responses to allogeneic cells or to mitogens in the mouse can be readily measured, the reliable assay of antigen-induced T-lymphocyte proliferation in culture has proved to be substantially more difficult to establish. The uncontrolled nature of proliferation and the contribution of B-cell responses have made these methods of questionable value as a T-cell assay. The novel features of the method are the use of only draining lymph node cells of primed mice instead of spleen cells and the use of horse serum in the culture medium instead of fetal calf serum. Only draining lymph node cells rich for antigen-reactive cells are used. Animals are sensitized by injecting antigen into the tail or footpads, the draining lymph nodes are removed, the cells are cultured in microculture plates in the presence or absence of antigens (and/or mitogens), and proliferation is measured by [3H] thymidine uptake. This technique can be used for several antigens, such as monovalent antigens and protein antigens. The Digestive Involvement in Systemic Autoimmune Diseases A.J. Czaja, in Handbook of Systemic Autoimmune Diseases, 2017 4.4 Regulatory T Cells Regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells modulate CD8 T cell proliferation by exerting a direct suppressive effect on the production of IFN-γ while increasing secretion of IL-4, IL-10, and TGF-β [143–146]. They can also induce the apoptosis of inflammatory and immune cells [147], inhibit hepatic stellate cells [148], impair the secretion of IL-17 [149], and limit the proliferation of Th17 lymphocytes [149]. These cells have been decreased in number and function in the peripheral blood of patients with autoimmune hepatitis [144,150,151], and they have been less evident in the portal tracts of liver specimens (Table 2.3) [151]. A signaling defect that influences the function of the regulatory T cells may also contribute to regulatory failure [5]. Galectin 9 is a beta galactosidase–binding protein expressed on regulatory T cells, and its ligation with the mucin domain-3 receptor (TIM-3) on Th1 cells and dendritic cells induces the apoptosis of Th1 lymphocytes and dendritic cells [152,153]. In autoimmune hepatitis, the expression of galectin 9 on regulatory T cells and TIM-3 on Th1 cells is reduced, and these deficiencies may limit the ability of the regulatory T cells to restore immune tolerance [153]. Deficiencies in the function of regulatory T cells have also been described in the siblings and children of patients with PBC, and the suppressor activity of this subset may be modulated by genetic factors [146]. Regulatory T cells can be defined more rigidly by the phenotype CD4+CD25+CD127+(low)Foxp3+, and cells with this phenotype have had normal function in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Furthermore, increased numbers of these cells have been described in the peripheral circulation and liver tissue of patients with autoimmune hepatitis [154]. These findings have challenged the hypothesis that perturbations in the regulatory T cell population are critical for the development of autoimmune hepatitis. The discrepant findings between studies may relate to differences in the phenotypic definition of the regulatory T cells, methods for the detection and evaluation of these cells, and the severity and treatment of the liver disease in the study population [155]. The abnormalities associated with regulatory T cells may be transient and improved by medications (corticosteroids, mycophenolate mofetil, or rapamycin) and the resolution of inflammatory activity [5,144]. Relative imbalances between the number and functions of the regulatory T cells and effectors cells may be the critical factor affecting the autoreactive response rather than the absolute number and function of an individual cell population.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

onto Immunology April 25, 2021 3:38 AM

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/buy-2-c-b-drug/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/buy-4-aco-dmt/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/buy-5-meo-dmt/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/ayahuasca-tea/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/buy-changa/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/dmt-vape-pen/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/golden-teacher-mushrooms/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/ibogaine-for-sale/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/ketamine-drug/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/buy-khat-plant-online/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/buy-kratom-powder-online/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/liberty-caps-mushrooms/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/liquid-lsd/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/buy-lsd-gel-tabs/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/buy-lsd-gummies/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/buy-lsd-tabs/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/mdma-drug/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/peyote-cactus/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/buy-pcp-drug/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/penis-envy-mushrooms/

https://vaporwavepsychedelic.com/product/buy-dmt/