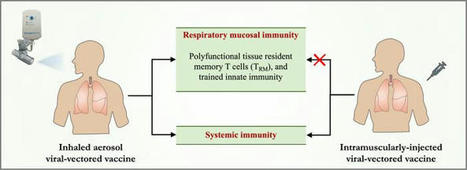

During the period of March 2019 to February 2021, we enrolled 36 BCG-vaccinated healthy adults between 18 and 55 years of age at McMaster University Medical Centre. Four participants were excluded (2 withdrew consent and 2 were withdrawn before vaccination because they were unable to comply with the study visit requirements) and 1 did not complete any follow-up visits after vaccination because of COVID restrictions. Thirty-one participants completed the study: 11 in the low-dose (LD) aerosol group, 11 in the high-dose (HD) aerosol group, and 9 in the i.m. group (Figure 1). The demographic and baseline characteristics of the study participants were similar among study groups (Table 1). Figure 1Trial profile. PPD, purified protein derivative; LD, low-dose aerosol; HD, high-dose aerosol; i.m.-intramuscular injection; PFU, plaque-forming unit. Table 1Demographics of participants. Characterization of inhaled aerosol delivery method and aerosol droplets using Aeroneb Solo device. The Aeroneb Solo Micropump was selected to be part of the device set up for aerosol generation and delivery in our study (Supplemental Figure 1; supplemental material available online with this article; https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.155655DS1). A fill volume (FV) of 0.5 mL in the nebulizer was determined to be optimal for vaccine delivery in saline. Subjects completed inhalation of this volume containing the vaccine via tidal breathing in approximately 2.5 minutes (Table 2). The emitted dose (ED) of vaccine available at the mouth was found to be approximately 50% of the loaded dose in the nebulizer (Table 2). The majority of aerosol droplets containing the vaccine were < 5.39 μm (85%), or between 2.08 and 5.39 μm in diameter, conducive to vaccine deposition in major airways. Thus, the amount of aerosol available at the mouth and subsequently deposited in the lung was 42.5% (16). The estimated rate of viable vaccine from aerosol droplets generated by the nebulizer was 17.4%. The dose loaded in the nebulizer for aerosol inhalation was, thus, corrected according to the estimated losses of vaccine within the device. Table 2Characterization of aerosol device and aerosol droplets. Safety of inhaled aerosol and i.m.-injected AdHu5Ag85A vaccine. Both LD (1 × 106 PFU) and HD (2 × 106 PFU) of AdHu5Ag85A administered by aerosol inhalation or the i.m. injection were safe and well tolerated. Respiratory adverse events were infrequent, mild, transient, and similar among groups (Table 3). I.m. injection was associated with a mild local injection site reaction in 2 participants. Systemic adverse events were also infrequent, mild, transient, and similar among groups (Table 3). One participant who received LD aerosol vaccine developed genital lesions consistent with primary HSV-1 infection the day following the week-2 bronchoscopy, and this condition resolved without complication with oral valacyclovir; one participant developed plantar fasciitis on day 13 following vaccination, which was attributed to mechanical strain and resolved with acetominophen. There were no grade 3 or 4 adverse events reported, nor any serious adverse events. Table 3Adverse events. There were no clinically significant abnormalities of laboratory tests at weeks 2, 4, and 12 following vaccination. Follow-up respiratory functional determinations forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1)and forced vital capacity (FVC) were similar to baseline values in all participants across all 3 groups (Figure 2, A and B). Figure 2Respiratory function and bronchoalveolar cellular responses following aerosol or intramuscular vaccination. (A and B) Lung function was assessed as FEV1 and FVC at baseline and 2 weeks after LD aerosol (n = 11), HD aerosol (n = 11), or i.m. (n = 9) vaccination. (C–F) Frequencies of differential cells including macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and epithelial cells in BALF from LD aerosol, HD aerosol, and i.m. vaccine cohorts. Violin plots show the median and quartiles. Data in dot plots are expressed as the mean value (horizontal line) with 95% CI. Wilcoxon matched pairs signed-rank test was used to compare various time points with baseline values within the same vaccination group. Bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage were generally well tolerated in all participants. As expected, in some participants, the procedures were associated with mild cough, sore throat, low-grade fever, headache, and a transient drop in FEV1. The appearance of the bronchial mucosa was judged as normal in all participants at each time point. Adequate bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) volumes were obtained following bronchoalveolar lavage, and on average, 10 to 20 million total cells were obtained. Aerosol AdHu5Ag85A vaccination induces robust and sustainable Th1 responses in the airway. Bronchoalveolar lavage was obtained successfully at baseline and at 2 and 8 weeks after vaccination from all participants with a median return volume of 87.5 mL (IQR, 72.5–98) from a total of 160 mL saline instilled and a median total cell number of 0.14 million/mL BALF (IQR, 0.1–0.2). Cellularity in the airway significantly increased 2 weeks after both LD and HD aerosol vaccination, and in the LD aerosol group, cellularity remained significantly heightened up to 8 weeks after vaccination compared with baseline (Figure 2C). Both LD and HD aerosol vaccination led to a transient reduction in airway macrophages, but the lymphocyte counts significantly increased only in LD cohort (Figure 2, D and E). Importantly, both neutrophils and epithelial cells in the airway remained either absent or unaltered following aerosol vaccination (Figure 2, D and E), indicating no significant airway inflammation except vaccine-induced lymphocytic responses. In comparison, there were no marked changes in total cellularity and any leukocyte subsets in the airway after i.m. vaccination (Figure 2, C and F). Evaluation of Th1 responses in the airways (BALF) cells was performed by intracellular cytokine immunostaining and flow cytometry (the gating strategy shown in Supplemental Figure 2). It showed that both LD and HD aerosol AdHu5Ag85A markedly increased Ag85A peptide pool–specific (Ag85A p. pool–specific) or reactive, IFN-γ–, TNF-α–, and/or IL-2–producing CD4+ T cells in the airways at 2 weeks after vaccination compared with the respective baseline responses (Figure 3, A–C). On average, the total Ag-specific cytokine-producing CD4+ T cells represented approximately 25% of all CD4+ T cells at 2 weeks after LD or HD aerosol, and they remained significantly elevated up to 8 weeks in the airways of LD cohort (Figure 3, A and B). In contrast, i.m. AdHu5Ag85A vaccination failed to induce Ag-specific CD4+ T cells in the airways (Figure 3A). Compared with CD4+ T cells, although the levels of airway CD8+ T cell responses were much smaller, they were significantly increased at both 2 and 8 weeks, particularly following LD aerosol vaccination (Figure 3D). Of interest, there was also a small but increased number of CD8+ T cells at 2 weeks after i.m. vaccination. Figure 3Induction of multifunctional T cells in the airways following aerosol or i.m. vaccination. (A) Frequencies of airway antigen–specific combined total-cytokine–producing CD4+ T cells at various time points in LD aerosol, HD aerosol, and i.m. cohorts. (B) Frequencies of airway single-cytokine–producing CD4+ T cells at various time points in LD aerosol cohort. (C) Frequencies of airway single-cytokine–producing CD4+ T cells at various time points in HD aerosol cohort. (D) Frequencies of airway antigen–specific combined total-cytokine–producing CD8+ T cells at various time points in LD aerosol, HD aerosol, and i.m. cohorts. (E) Representative dot plots of airways CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 at wk2 from LD aerosol participants. (F) Frequencies of airways polyfunctional (triple/3+, double/2+, and single/1+ cytokine+) antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at various time points in LD aerosol group. (G) Median proportions displayed in pie chart of antigen-specific airways CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing a specific single or combination of 2 or 3 cytokines at various time points in LD aerosol group. Data in dot plots are expressed as the mean value (horizontal line) with 95% CI. Box plots show mean value (horizontal line) with 95% CI (whiskers), and boxes extend from the 25th to 75th percentiles. Wilcoxon matched pairs signed-rank test was used to compare various time points with baseline values within the same vaccination group. Analysis of polyfunctionality of vaccine-activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells reactive to Ag85A in the airways revealed that LD aerosol vaccination led to induction of a higher magnitude of CD4+ T cells that coexpressed IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 (3+) and any of 2 cytokines (2+) compared with those producing single cytokine (1+) (Figure 3, E and F). Importantly, polyfunctional CD4+ T cells remained significantly increased over the baseline up to 8 weeks. Similarly, LD aerosol vaccination also significantly increased the polyfunctional CD8+ T cells, particularly at 8 weeks, in the airways, though at a much lower overall magnitude compared with CD4+ T cells (Figure 3F). In comparison, HD aerosol vaccination led to significantly increased polyfunctional CD4+ but not CD8+ T cells reactive to Ag85A (Supplemental Figure 3, A and B). Given that the LD aerosol AdHu5Ag85A was consistently highly immunogenic, we profiled the polyfunctional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the airways of the LD cohort in greater detail. While at 2 weeks, a greater proportion of Ag85A-reactive CD4+ T cells were polyfunctional (IFN-γ+TNF-α+IL-2+, IFN-γ+TNF-α+, or IFN-γ+IL-2+), with some of them also being single cytokine producers, at 8 weeks, the vast majority of them (>95%) became polyfunctional (Figure 3G). In comparison, most of the CD8+ T cells at 2 weeks were single-cytokine producers (TNF-α+), but at 8 weeks, the majority of them turned to be polyfunctional, mostly being IFN-γ+TNF-α+ (Figure 3G). Since the trial participants were previously BCG vaccinated, we examined the overall T cell reactivity to stimulation with multimycobacterial antigens. We found considerable CD4+ T cells present in the airways to be reactive to a cocktail of mycobacterial antigens even prior to vaccination, and they remained unaltered after LD, HD, or i.m. vaccination (Supplemental Figure 3C). These BCG-specific CD4+ T cells in the airways of LD group were mostly polyfunctional (Supplemental Figure 3, D and E). Similarly, small numbers of preexisting BCG-specific CD8+ T cells in the airways were not altered by aerosol or i.m. vaccination (Supplemental Figure 3F). The above data suggest that inhaled aerosol, but not i.m., AdHu5Ag85A vaccination can induce robust antigen-specific T cell responses within the respiratory tract. Furthermore, a LD (1 × 106 PFU) aerosol vaccination is superior to a HD (2 × 106 PFU) aerosol in inducing robust and sustainable respiratory mucosal immunity. The mucosal responses induced by AdHu5Ag85A vaccine are predominantly polyfunctional CD4+ T cells in nature, with some levels of polyfunctional CD8+ T cells. The preexisting CD4+ T cells of multimycobacterial antigen specificities in the airway of BCG-vaccinated trial participants were not significantly impacted by AdHu5Ag85A aerosol vaccination. Aerosol vaccination induces airway TRM expressing the lung-homing molecule α4β1 integrin. Lung tissue TRM are critical to protective mucosal immunity (17). Hence, we next determined whether antigen-specific T cells induced by aerosol AdHu5Ag85A vaccination were of tissue-resident memory phenotype and compared them with those induced by i.m. vaccination. BALF cells obtained before and at select time points after vaccination were stimulated with Ag85A p. pool and immunostained for coexpression of 2 key TRM surface markers CD69 and CD103 by antigen-specific IFN-γ–producing CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (Figure 4A). Marked increases in Ag85A-specific IFN-γ+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells coexpressing CD69 and CD103 were seen only in the airway of LD and HD aerosol vaccine groups and not in i.m. group (Figure 4, B and C). Although TRM increases at 8 weeks after aerosol vaccination, compared with the baseline, were only marginally statistically significant (95% CI) probably due to small sample sizes, remarkable proportions of Ag85A-specific CD4 T cells (~20%) and CD8+ T cells (~54%) present in the airways of aerosol vaccine groups were TRM (Figure 4D). As expected, there was no detectable antigen-specific TRM in the peripheral blood before and after vaccination. Figure 4Induction of airway tissue TRM following aerosol or i.m. vaccination. (A) Representative dot plots of airway antigen–specific CD4+ and CD8+ TRM at wk2 in LD aerosol participants. (B) Frequencies of airway antigen–specific IFN-γ+CD4+ TRM coexpressing CD69 and CD103 surface markers at various time points in LD aerosol, HD aerosol, and i.m. vaccine cohorts. (C) Frequencies of airway antigen–specific IFN-γ+CD8+ TRM coexpressing CD69 and CD103 at various time points in LD aerosol, HD aerosol, and i.m. vaccine cohorts. (D) Comparison of frequencies of airway antigen–specific CD4+ and CD8+ TRM coexpressing CD69 and CD103 at 8 weeks after LD and HD aerosol vaccination. (E) Representative dot plots of peripheral blood antigen–specific IFN-γ+CD4+ T cells expressing CD49d at wk2 from LD aerosol participants, and frequencies of circulating antigen-specific CD4+ T cells expressing CD49d at various time points in LD aerosol, HD aerosol, and i.m. vaccine cohorts. (F) Representative dot plots of airway antigen–specific IFN-γ+CD4+ T cells expressing CD49d at wk2 from LD aerosol participants, and frequencies of airway antigen–specific CD4+ T cells expressing CD49d at various time points in LD aerosol, HD aerosol, and i.m. vaccine cohorts. (G) Comparison of frequencies of airway antigen–specific IFN-γ+CD4+ T cells coexpressing CD49d at the peak time point in LD aerosol, HD aerosol, and i.m. vaccine cohorts. Data in dot plots are expressed as the mean value (horizontal line) with 95% CI. Wilcoxon matched pairs signed-rank test (B, C, E, and F) was used to compare various time points with baseline values within the same vaccination group. Mann-Whitney U test (D and G) was used when comparing between vaccination groups. We also studied T cell surface expression of α4β1 integrin (VLA-4; or CD49d for α4), known to be expressed on memory CD4+ T cells in human airways (18). Since CD49d may be involved in the homing of circulating T cells to the airway, we first examined CD49d expression on Ag85A-specific CD4+ T cells in the circulation. There were small but significantly increased frequencies of circulating CD49d-expressing IFN-γ+CD4+ T cells, particularly at 2 weeks following LD or HD aerosol vaccination (Figure 4E). In comparison, there were much greater frequencies of CD49d-expressing IFN-γ+CD4+ T cells (out of total CD4+ T cells) in the airways induced by aerosol vaccination (Figure 4F), compared with their frequencies in the circulation (Figure 4E) and in contrast with the lack of such T cells in the airways of i.m. group (Figure 4G). In fact, the majority of Ag85A-specific CD4+ T cells in the airways of LD and HD groups expressed CD49d (57% and 74%, respectively). The data indicate that aerosol AdHu5Ag85A vaccination, but not i.m. route of vaccination, is uniquely capable of inducing antigen-specific T cells in the airways endowed with respiratory mucosal homing and TRM properties. Since, besides mucosal adaptive immunity, respiratory delivery of AdHu5Ag85A vaccine in experimental animals induced a trained phenotype in airway macrophages (6, 19), we examined whether aerosol vaccination could also alter the immune property of human alveolar macrophages (AM). To this end, we elected to examine the transcriptomics of BALF cells obtained from 5 participants before (week 0 [wk0]) and after (week 8 [wk8]) LD aerosol vaccination. Before RNA isolation, the cells, upon revival from frozen stock, were enriched for AM and cultured with or without stimulation with M. tuberculosis lysates and transcriptionally profiled by RNA-Seq analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that unstimulated and stimulated AM populations were separated away from each other (Figure 5A). We then identified the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) by comparing wk0-stimulated (Group 3–stimulated) and wk8-stimulated (Group 4–stimulated) AM with respective unstimulated AM (wk0/Group 1) and wk8/Group 2). A total of 2726 genes was differentially expressed upon stimulation in pairwise analysis, of which 1667 genes (61%) were shared between the baseline (wk0) Group 3/Group 1 and aerosol vaccine (wk8) Group 4/Group 2 (Figure 5B). As expected, the shared genes were significantly enriched in biological processes associated with immune response and regulation of cell death (Figure 5C). Furthermore, by pairwise analysis, we identified 191 and 426 genes uniquely upregulated and downregulated, respectively, in stimulated aerosol (Group 4) AM (Figure 5D). The uniquely upregulated genes in stimulated wk8 aerosol AM showed enrichment in a number of biological processes including response to anoxia (OXTR, CTGF), inflammatory response to antigenic stimuli (IL-2RA, IL-1B, IL-20RB), tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT protein (IFN-γ, F2R, OSM), regulation of IL-10 production (CD83, IRF4, IL-20RB, IDO1), response to IL-1 (RIPK2, SRC, IRAK2, IL-1R1, XYLT1, RELA), and histone demethylation (KDM6B, KDM5B, KDM1A, KDM7A, JMJD6; Figure 5E). In comparison, the uniquely downregulated genes in wk8 aerosol AM did not appear significantly enriched for any biological processes. These data suggest that LD aerosol vaccination leads to persisting transcriptional changes in airway-resident AM poised for defense responses. Figure 5Transcriptomic analysis of alveolar macrophages (AM) following LD aerosol vaccination. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) of gene expression in AM obtained before (wk0) and after (wk8) LD aerosol vaccination cultured with (S) or without (US) stimulation. (B) Venn diagram comparing all DEGs in pairwise comparison. (C) Significantly enriched functional categories of biological processes by GO associated with DEGs shared between the baseline (wk0) Group 3/1 and aerosol vaccine (wk8) Group 4/2. (D) Venn diagram comparing up- and downregulated DEGs in pairwise comparison. Heatmap shows DEG uniquely up- and downregulated, in stimulated aerosol (Group 4) AM. (E) Significantly enriched functional categories of biological processes by GO associated with uniquely upregulated DEGs in stimulated aerosol (Group 4) AM. Statistical differences in functional categories of biological processes was performed using BINGO plugin, which uses a hypergeometric test with Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction. Both aerosol and i.m. vaccination induce systemic Th1 responses. Assessment of overall antigen-specific reactivity of T cells in the circulation before and after vaccination by using whole blood samples incubated with Ag85A peptides indicated that both aerosol, particularly LD aerosol, and i.m. AdHu5Ag85A vaccination induced significant systemic immune responses, as shown by raised IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 levels in plasma (Figure 6, A–C). AUC analysis, which reflects the overall magnitude of responses, did not differ between LD aerosol and i.m. groups in cytokine production in response to Ag85A p. pool stimulation (IFN-γ, P = 0.0910; TNF-α, P = 0.6207; IL-2, P = 0.8703). However, i.m. vaccine–induced systemic T cell responses appeared to remain significantly increased over a longer duration (Figure 6C). In comparison, the HD aerosol group had significantly lower IFN-γ production than i.m. group (AUC compared with i.m., P = 0.0117) whereas they did not differ from each other in the production of TNF-α and IL-2 (Figure 6, B and C). Figure 6Induction of antigen-specific T cell responses in the peripheral blood following aerosol or intramuscular vaccination. (A–C) Antigen-specific cytokine production in whole blood culture at various time points after LD aerosol, HD aerosol, and i.m. vaccine groups. The measurements were subtracted from unstimulated control values. (D) Frequencies of peripheral blood antigen–specific combined total-cytokine-producing CD4+ T cells at various time points in LD aerosol, HD aerosol, and i.m. cohorts. (E) Frequencies of peripheral blood polyfunctional (triple/3+, double/2+, and single/1+ cytokine+) antigen-specific CD4+ T cells at various time points in LD aerosol, HD aerosol, and i.m. vaccine groups. (F) Frequencies of peripheral blood antigen–specific combined total-cytokine–producing CD8+ T cells at various time points in LD aerosol, HD aerosol, and i.m. groups. (G) Frequencies of peripheral blood polyfunctional (triple/3+, double/2+ and single/1+ cytokine+) antigen-specific CD8+ T cells at various time points in LD aerosol, HD aerosol, and i.m. groups. Data in dot plots are expressed as the mean value (horizontal line) with 95% CI. Box plots show mean value (horizontal line) with 95% CI (whiskers), and boxes extend from the 25th to 75th percentiles. Line graphs show median with IQR. Wilcoxon matched pairs signed-rank test (A, B, E, and G) was used to compare various time points with baseline values within the same vaccination group. Mann-Whitney U test (D and F) was used when comparing vaccination groups. Further examination of relative activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by aerosol and i.m. vaccinations using intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) revealed that, compared with the respective baseline, aerosol vaccination activated the circulating Ag85A-specific CD4+ T cells to significant levels, while i.m. vaccination moderately increased such responses (Figure 6D). However, the overall magnitude of responses did not differ significantly between aerosol and i.m. groups (AUC: LD aerosol, P = 0.1961; HD aerosol, P = 0.3545 compared with i.m.). Both LD/HD aerosol and i.m. vaccination also significantly increased Ag85A-specific polyfunctional CD4+ T cells coexpressing 3 (3+) or any 2 (2+) cytokines in the circulation (Figure 6E). Consistent with the airway Ag85A-specific CD4+ T cell responses (Figure 3, A–C) in both LD and HD aerosol groups, circulating polyfunctional CD4+ T cells also generally peaked at 2 weeks after vaccination and remained significantly increased up to 8 weeks (Figure 6E). In comparison, 3+ polyfunctional CD4+ T cells in the i.m. group significantly increased at 4 weeks and remained increased up to 8 weeks (Figure 6E). The overall magnitude of circulating 3+ polyfunctional CD4+ T cells in the i.m. group was, however, significantly higher than those in aerosol groups (AUC: LD aerosol, P = 0.0144; HD aerosol, P = 0.0393 compared with i.m.). Circulating 2+ polyfunctional CD4+ T cells did not differ significantly between these groups (AUC not significantly different). Consistent with our previous observation (8), besides its activating effects on circulating CD4+ T cells, i.m. vaccination also significantly increased Ag85A-specific CD8+ T cells up to 16 weeks (Figure 6F). By comparison, aerosol vaccination minimally induced such CD8+ T cells in the circulation (Figure 6F). Compared with circulating CD4+ T cells (Figure 6E), similar to the overall kinetics of total-cytokine+ CD8+ T cells (Figure 6F), circulating Ag85A-specific polyfunctional CD8+ T cells peaked behind the peak CD4+ T cell responses in all vaccine groups (Figure 6G). The kinetics of polyfunctional profiles of circulating CD4+ T cells were further examined in greater detail with a focus on the LD aerosol vaccine group and its comparison with the i.m. group. There existed considerable differences in the polyfunctional profile of circulating Ag85A-specific CD4+ T cells between LD aerosol and i.m. groups (Supplemental Figure 4A). In the LD aerosol group, the proportion of IFN-γ+TNF-α+IL-2+ progressively shrank, and at 16 weeks, approximately 75% of the population were TNF-α+IL-2+ and IFN-γ+TNF-α+ together with single TNF-α+ CD4+ T cells. In comparison, in the i.m. group, the proportion of IFN-γ+TNF-α+IL-2+ progressively expanded, constituting approximately 75% of the population at 16 weeks (Supplemental Figure 4A). Upon examination of circulating BCG-specific CD4+ T cells (reactive to M. tuberculosisCF+ rAg85A stimulation), we found that they were not strikingly increased in aerosol and i.m. vaccine groups, although the trend was higher in i.m. group (Supplemental Figure 4, B and C), and AUC values did not differ significantly between aerosol and i.m. groups (LD aerosol, P = 0.0870; HD aerosol, P = 0.2666, compared with i.m.). However, LD and HD aerosol vaccination had a significant enhancing effect on the polyfunctionality of preexisting circulating BCG-specific CD4+ T cells (Supplemental Figure 4C). Similar to BCG-specific circulating CD4+ T cells (Supplemental Figure 4B), BCG-specific circulating CD8+ T cells were not significantly increased by either aerosol or i.m. vaccination (Supplemental Figure 4D). These data indicate that, besides markedly induced mucosal T cell immunity (Figures 3 and 4), respiratory mucosal vaccination via inhaled aerosol, particularly LD aerosol, can also induce systemic polyfunctional CD4+ T cell responses, similar to i.m. route of vaccination in previously BCG-vaccinated humans. Preexisting and vaccine-induced anti-AdHu5 Ab in the circulation and airways. The high prevalence of circulating preexisting antibodies (Ab) against AdHu5 in human populations may negatively impact the potency of AdHu5-vectored vaccines following i.m. administration (20). However, little is known about its effect on the potency of AdHu5-vectored vaccine delivered via the respiratory mucosa. To address this question, we first examined the levels of AdHu5-specific total IgG in the circulation and airways (BALF) before and after vaccination (wk0 versus wk4 in circulation; wk0 versus wk8 in BALF). In keeping with our previous findings (8), there were significant levels of preexisting circulating AdHu5-specific total IgG in most of the trial participants (1 × 104 to 1 × 105), and the levels were comparable between the groups (using Kruskal-Wallis test P = 0.2048; Table 4). These titres significantly increased after HD aerosol or i.m. AdHu5Ag85A vaccination but not after LD aerosol vaccination. In comparison, preexisting levels of anti-AdHu5 total IgG in the airways were 1 to 1.5 log less than the levels in the circulation and were comparable between groups (using Kruskal-Wallis test, P = 0.2048). Of interest, LD and HD aerosol, as well as i.m. vaccination, did not alter the preexisting anti-AdHu5 total IgG levels in the airways (Table 4), but the data from HD aerosol and i.m. groups should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size at 8 weeks. Table 4Anti-Ad5 antibody titers before and after LD aerosol, HD aerosol, and i.m. vaccination. Because the total anti-AdHu5 Ab titres may not always correlate with AdHu5-neutralizing capacity in the circulation (8), we further assessed the AdHu5-neutralizing Ab (nAb) titres before and after vaccination in the circulation and airways by using a bioassay. The preexisting AdHu5 nAb titres in the circulation were comparable between groups (using Kruskal-Wallis test, P = 0.3588) with 27%, 54%, and 66% of participants in LD, HD, and i.m. groups having > 1 × 102 AdHu5 nAb titres, respectively. Of interest, while i.m. vaccination with AdHu5Ag85A significantly increased the circulating AdHu5 nAb titers by an average of 1.5 logs, LD or HD aerosol vaccination had no such effect (Table 4). On the other hand, similar to total anti-AdHu5 IgG levels, preexisting AdHu5 nAb titers in the airways were ~1 log less than those in the circulation (Table 4). Of importance, 63%, 36%, and 33% of participants in LD, HD., and i.m. groups, respectively, had no detectable baseline AdHu5 nAb titers in their airways, which remained unaltered following vaccination (Table 4). We further found a significant positive correlation between AdHu5 nAb and total AdHu5 IgG titres both in the circulation and airways (Supplemental Figure 5, A and B). Given that many of the trial participants had moderate to significant levels of AdHu5 nAb titers in the circulation and ~50% of them also had a small but detectable level of preexisting AdHu5 nAb titres in the airways, we next examined whether such nAbs present in the airways and blood may have negatively impacted the immunopotency of LD aerosol and i.m. vaccination, respectively. To this end, the percentage of airways or blood with total-cytokine+ Ag85A-specific CD4+ T cells at the peak response time (2 weeks post-vaccination) for individual participants was plotted against corresponding preexisting AdHu5 nAb titres, and Spearman rank correlation test was performed. There was no significant correlation between preexisting airways AdHu5 nAb titers and the magnitude of vaccine-induced CD4+ (Supplemental Figure 5C) and CD8+ (Supplemental Figure 5D) T cell responses in the airways following LD aerosol vaccination. Of note, one participant who hardly responded to aerosol vaccine did have the highest neutralization titers in the cohort (Supplemental Figure 5, C and D). On the other hand, consistent with our previous observation (8), there was no significant correlation between preexisting circulating AdHu5 nAb titers and the magnitude of antigen-specific CD4+ (Supplemental Figure 5E) and CD8+ (Supplemental Figure 5F) T cell responses in the blood following i.m. vaccination. The above data suggest that, while there is high prevalence of preexisting circulating anti-AdHu5 nAb in humans enrolled in our study, most trial participants have either undetectable or very low levels of preexisting anti-AdHu5 nAb titers in the airways. I.m. AdHu5Ag85A vaccination increases AdHu5 nAb titers in the circulation, whereas aerosol vaccination does not do so either in the airways or in the circulation. Although the presence of AdHu5 nAb in the airways does not seem to have a significant impact on aerosol vaccine immunogenicity, the data should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size and very few BALF samples with significant AdHu5 nAb titers.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

onto Mucosal Immunity October 12, 2022 10:22 AM

|

No comment yet.

Sign up to comment

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...