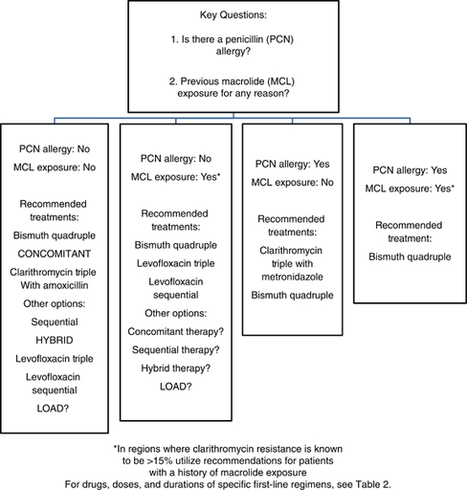

Download PDF William D. Chey, MD, FACG1, Grigorios I. Leontiadis, MD, PhD2, Colin W. Howden, MD, FACG3 and Steven F. Moss, MD, FACG4 1Division of Gastroenterology, University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA; 2Division of Gastroenterology, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; 3Division of Gastroenterology, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, Tennessee, USA; and 4Division of Gastroenterology, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112: 212–238; doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.563; published online 10 January 2017 Received 28 June 2016; accepted 7 October 2016 Correspondence: William D. Chey, MD, FACG, Timothy T. Nostrant Professor of Gastroenterology and Nutrition Sciences, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Michigan Health System, 3912 Taubman Center, SPC 5362, Ann Arbor, Michigan 49109-5362, USA. E-mail: wchey@umich.edu Abstract Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is a common worldwide infection that is an important cause of peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer. H. pylori may also have a role in uninvestigated and functional dyspepsia, ulcer risk in patients taking low-dose aspirin or starting therapy with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication, unexplained iron deficiency anemia, and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. While choosing a treatment regimen for H. pylori, patients should be asked about previous antibiotic exposure and this information should be incorporated into the decision-making process. For first-line treatment, clarithromycin triple therapy should be confined to patients with no previous history of macrolide exposure who reside in areas where clarithromycin resistance amongst H. pylori isolates is known to be low. Most patients will be better served by first-line treatment with bismuth quadruple therapy or concomitant therapy consisting of a PPI, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, and metronidazole. When first-line therapy fails, a salvage regimen should avoid antibiotics that were previously used. If a patient received a first-line treatment containing clarithromycin, bismuth quadruple therapy or levofloxacin salvage regimens are the preferred treatment options. If a patient received first-line bismuth quadruple therapy, clarithromycin or levofloxacin-containing salvage regimens are the preferred treatment options. Details regarding the drugs, doses and durations of the recommended and suggested first-line and salvage regimens can be found in the guideline. Introduction Helicobacter pylori infection remains one of the most common chronic bacterial infections affecting humans. Since publication of the last American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Clinical Guideline in 2007, significant scientific advances have been made regarding the management of H. pylori infection. The most significant advances have been made in the arena of medical treatment. Thus, this guideline is intended to provide clinicians working in North America with updated recommendations on the treatment of H. pylori infection. For the purposes of this document, we have defined North America as the United States and Canada. Whenever possible, recommendations are based upon the best available evidence from the world’s literature with special attention paid to literature from North America. When evidence from North America was not available, recommendations were based upon data from international studies and expert consensus. This guidance document was developed using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system (1), which provides a level of evidence and strength of recommendation for statements developed using the PICO (patient population, intervention or indicator assessed, comparison group, outcome achieved) format. At the start of the guideline development process, the authors developed PICO questions relevant to Helicobacter pylori infection. The authors worked with research methodologists from McMaster University to conduct focused literature searches to provide the best available evidence to address the PICO questions. Databases searched included MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane CENTRAL from 2000 to 11 September 2014. Search terms included “pylori, treat*, therap*, manag*, eradicat*”. The full literature search strategy is provided as Supplementary Appendix 1 online. After assessing the risk of bias, indirectness, inconsistency, and imprecision, the level of evidence for each recommendation was reported as “high” (further research is unlikely to change the confidence in the estimate of effect), “moderate” (further research would be likely to have an impact on the confidence in the estimate of effect), “low” (further research would be expected to have an impact on the confidence in the estimate of effect), or “very low” (any estimate of effect is very uncertain). The strength of recommendations was determined to be “strong” or “conditional” based on the quality of evidence, the certainty about the balance between desirable and undesirable effects of the intervention, the certainty about patients’ values and preferences, and the certainty about whether the recommendation represents a wise use of resources. A summary of the recommendation statements for this management guideline is provided in Table 1. The justification for the assessments of the quality of evidence for each statement can be found in Supplementary Appendix 2 online. Table 1. Recommendation statements What is known about the epidemiology of H. pylori infection in North America? Which are the high risk groups? H. pylori infection is chronic and is usually acquired in childhood. The exact means of acquisition is not always clear. The incidence and prevalence of H. pylori infection are generally higher among people born outside North America than among people born here. Within North America, the prevalence of the infection is higher in certain racial and ethnic groups, the socially disadvantaged, and people who have immigrated to North America (Factual statement, low quality of evidence). What are the indications to test for, and to treat, H. pylori infection? Since all patients with a positive test of active infection with H. pylori should be offered treatment, the critical issue is which patients should be tested for the infection (strong recommendation; quality of evidence not applicable). All patients with active peptic ulcer disease (PUD), a past history of PUD (unless previous cure of H. pylori infection has been documented), low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, or a history of endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer (EGC) should be tested for H. pylori infection. Those who test positive should be offered treatment for the infection (Strong recommendation; quality of evidence: high for active or history of PUD, low for MALT lymphoma, low for history of endoscopic resection of EGC). In patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia who are under the age of 60 years and without alarm features, non-endoscopic testing for H. pylori infection is a consideration. Those who test positive should be offered eradication therapy (conditional recommendation; quality of evidence: high for efficacy, low for the age threshold). When upper endoscopy is undertaken in patients with dyspepsia, gastric biopsies should be taken to evaluate for H. pylori infection. Infected patients should be offered eradication therapy (strong recommendation; high quality of evidence). Patients with typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) who do not have a history of PUD need not be tested for H. pylori infection. However, for those who are tested and found to be infected, treatment should be offered, acknowledging that effects on GERD symptoms are unpredictable (strong recommendation; high quality of evidence). In patients taking long-term, low-dose aspirin, testing for H. pylori infection could be considered to reduce the risk of ulcer bleeding. Those who test positive should be offered eradication therapy to reduce the risk of ulcer bleeding (conditional recommendation; moderate quality of evidence). Patients initiating chronic treatment with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) should be tested for H. pylori infection. Those who test positive should be offered eradication therapy (Strong recommendation; Moderate quality of evidence). The benefit of testing and treating H. pylori in a patient already taking an NSAID remains unclear (conditional recommendation; low quality of evidence). Patients with unexplained iron deficiency anemia despite an appropriate evaluation should be tested for H. pylori infection. Those who test positive should be offered eradication therapy (conditional recommendation; low quality of evidence). Adults with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) should be tested for H. pylori infection. Those who test positive should be offered eradication therapy (conditional recommendation; very low quality of evidence). There is insufficient evidence to support routine testing for and treatment of H. pylori in asymptomatic individuals with a family history of gastric cancer or patients with lymphocytic gastritis, hyperplastic gastric polyps, and hyperemesis gravidarum (no recommendation; very low quality of evidence). What are evidence-based first-line treatment strategies for providers in North America? Patients should be asked about any previous antibiotic exposure(s) and this information should be taken into consideration when choosing an H. pylori treatment regimen (conditional recommendation; moderate quality of evidence). Clarithromycin triple therapy consisting of a PPI, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin or metronidazole for 14 days remains a recommended treatment in regions where H. pylori clarithromycin resistance is known to be <15% and in patients with no previous history of macrolide exposure for any reason (Conditional recommendation; low quality of evidence (for duration: moderate quality of evidence)). Bismuth quadruple therapy consisting of a PPI, bismuth, tetracycline, and a nitroimidazole for 10–14 days is a recommended first-line treatment option. Bismuth quadruple therapy is particularly attractive in patients with any previous macrolide exposure or who are allergic to penicillin (strong recommendation; low quality of evidence). Concomitant therapy consisting of a PPI, clarithromycin, amoxicillin and a nitroimidazole for 10–14 days is a recommended first-line treatment option (strong recommendation; low quality of evidence (for duration: very low quality of evidence)). Sequential therapy consisting of a PPI and amoxicillin for 5–7 days followed by a PPI, clarithromycin, and a nitroimidazole for 5–7 days is a suggested first-line treatment option (conditional recommendation; low quality of evidence (for duration: very low quality of evidence)). Hybrid therapy consisting of a PPI and amoxicillin for 7 days followed by a PPI, amoxicillin, clarithromycin and a nitroimidazole for 7 days is a suggested first-line treatment option (conditional recommendation; low quality of evidence (For duration: very low quality of evidence)). Levofloxacin triple therapy consisting of a PPI, levofloxacin, and amoxicillin for 10–14 days is a suggested first-line treatment option (conditional recommendation; low quality of evidence (For duration: very low quality of evidence)). Fluoroquinolone sequential therapy consisting of a PPI and amoxicillin for 5–7 days followed by a PPI, fluoroquinolone, and nitroimidazole for 5–7 days is a suggested first-line treatment option (conditional recommendation; low quality of evidence (for duration: very low quality of evidence)). What factors predict successful eradication when treating H. pylori infection? The main determinants of successful H. pylori eradication are the choice of regimen, the patient’s adherence to a multi-drug regimen with frequent side-effects, and the sensitivity of the H. pylori strain to the combination of antibiotics administered (Factual statement; moderate quality of evidence). What do we know about H. pylori antimicrobial resistance in the North America? Data regarding antibiotic resistance among H. pylori strains from North America remains scarce. Organized efforts are needed to document local, regional, and national patterns of resistance in order to guide the appropriate selection of H. pylori therapy (strong recommendation; low quality of evidence). What methods can be used to evaluate for H. pylori antibiotic resistance and when should testing be performed? Although H. pylori antimicrobial resistance can be determined by culture and/or molecular testing, (strong recommendation; moderate quality of evidence), these tests are currently not widely available in the United States. Should we test for teatment success after H. pylori eradication therapy? Whenever H. pylori infection is identified and treated, testing to prove eradication should be performed using a urea breath test, fecal antigen test or biopsy-based testing at least 4 weeks after the completion of antibiotic therapy and after PPI therapy has been withheld for 1–2 weeks. (Strong recommendation; Low quality of evidence (for the choice of methods to test for eradication: Moderate quality of evidence)). When first-line therapy fails, what are the options for salvage therapy? In patients with persistent H. pylori infection, every effort should be made to avoid antibiotics that have been previously taken by the patient (unchanged from previous ACG guideline (1)) (Strong recommendation; moderate quality of evidence). Bismuth quadruple therapy or levofloxacin salvage regimens are the preferred treatment options if a patient received a first-line treatment containing clarithromycin. Selection of best salvage regimen should be directed by local antimicrobial resistance data and the patient’s previous exposure to antibiotics (Conditional recommendation; for quality of evidence see individual statements below). Clarithromycin or levofloxacin-containing salvage regimens are the preferred treatment options, if a patient received first-line bismuth quadruple therapy. Selection of best salvage regimen should be directed by local antimicrobial resistance data and the patient’s previous exposure to antibiotics (Conditional recommendation; for quality of evidence see individual statements below). The following regimens can be considered for use as salvage treatment: Bismuth quadruple therapy for 14 days is a recommended salvage regimen. (Strong recommendation; low quality of evidence) Levofloxacin triple regimen for 14 days is a recommended salvage regimen. (Strong recommendation; moderate quality of evidence (For duration: low quality of evidence) Concomitant therapy for 10–14 days is a suggested salvage regimen. (conditional recommendation; very low quality of evidence) Clarithromycin triple therapy should be avoided as a salvage regimen. (conditional recommendation; low quality of evidence) Rifabutin triple regimen consisting of a PPI, amoxicillin, and rifabutin for 10 days is a suggested salvage regimen (conditional recommendation; moderate quality of evidence (For duration: very low quality of evidence)). High-dose dual therapy consisting of a PPI and amoxicillin for 14 days is a suggested salvage regimen (conditional recommendation; low quality of evidence (For duration: very low quality of evidence)). When should penicillin allergy testing be considered in patients with H. pylori infection? Most patients with a history of penicillin allergy do not have true penicillin hypersensitivity. After failure of first-line therapy, such patients should be considered for referral for allergy testing since the vast majority can ultimately be safely given amoxicillin-containing salvage regimens (strong recommendation; Low quality of evidence). Question 1: What Is Known About the Epidemiology of H. pylori Infection in North America? Which Are the High-Risk Groups? Recommendation H. pylori infection is chronic and is usually acquired in childhood. The exact means of acquisition is not always clear. The incidence and prevalence of H. pylori infection are generally higher among people born outside North America than among people born here. Within North America, the prevalence of the infection is higher in certain racial and ethnic groups, the socially disadvantaged, and people who have immigrated to North America (factual statement, low quality of evidence). H. pylori infection is usually acquired during childhood (2, 3, 4, 5, 6) although the exact means of acquisition is not always clear. Risk factors for acquiring the infection include low socioeconomic status (6, 7, 8) increasing number of siblings (9) and having an infected parent—especially an infected mother (10). In the Ulm (Germany) Birth Cohort Study, the odds ratio (OR) for acquiring H. pylori infection if a child’s mother was infected was 13.0 (95% confidence interval (CI) 3.0–55.2) (10) Apart from intra-familial spread, the infection may also be transmitted through contaminated water supplies (11) particularly in developing countries. Although infection rates for male and female children are similar (3, 12) there may be a slight male preponderance of the infection in adulthood. In a meta-analysis of observational, population-based studies, men were slightly more likely to be H. pylori-positive than women; OR=1.16 (95% CI 1.11–1.22) (12) This was confirmed in a study of adults in Ontario, Canada, in which the overall seroprevalence was 23.1% but higher in men (29.4%) than women (14.9%) (13). One explanation that has been proposed for the lower seroprevalence in women is that they may be more likely to clear H. pylori infection because of higher rates of incidental antibiotic use for other indications (12). There is evidence for a birth cohort effect on H. pylori prevalence; for example, people who were born in the 1930s are more likely to have been infected during childhood than people born in the 1960s. In a study conducted among 7310 US veterans with gastrointestinal symptoms, seroprevalence was 73% among those born before 1920 and 22% in those born after 1980 (14). The overall prevalence of the infection in these US veterans fell from 70.8% in 1997 to a plateau of around 50% after 2002. Within North America, the prevalence of H. pylori infection varies with socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity (14, 15, 16, 17). In general, the prevalence is lower among non-Hispanic whites than among other racial/ethnic groups including African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Native Americans, and Alaska natives (5, 14, 15, 18). African Americans with a higher proportion of African ancestry have been reported to have higher rates of H. pylori infection than African Americans with a lower proportion of African ancestry suggesting that racial/genetic factors may have some role in predisposition to the infection unrelated to socioeconomic factors (16). Higher prevalence rates have been found among those living close to the US/Mexico border (19, 20); in one study (19), prevalence of H. pylori assessed by stool antigen testing was 38.2%. Prevalence has also been reported to be high among Alaska natives (18) and Canadian First Nations populations (21). The prevalence of H. pylori infection is generally lower in the United States than in many other parts of the world, particularly in comparison to Asia and Central and South America (8, 22). There is, however, preliminary evidence that it may be falling in some previously high prevalence areas (22). People immigrating to North America from Asia and other parts of the world have a much higher prevalence of the infection than people born in North America (23). In one study, the seroprevalence among immigrants from East Asia was 70.1% (24). Hispanic immigrants to North America have higher rates of the infection than first- or second-generation Hispanics who were born here (25). Question 2: What Are the Indications to Test For, and to Treat, H. pylori Infection? Recommendations Since all patients with a positive test of active infection with H. pylori should be offered treatment, the critical issue is which patients should be tested for the infection (strong recommendation, quality of evidence: not applicable), All patients with active peptic ulcer disease (PUD), a past history of PUD (unless previous cure of H. pylori infection has been documented), low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, or a history of endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer (EGC) should be tested for H. pylori infection. Those who test positive should be offered treatment for the infection (strong recommendation, quality of evidence: high for active or history of PUD, low for MALT lymphoma, low for history of endoscopic resection of EGC). In patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia who are under the age of 60 years and without alarm features, non-endoscopic testing for H. pylori infection is a consideration. Those who test positive should be offered eradication therapy (conditional recommendation, quality of evidence: high for efficacy, low for the age threshold). When upper endoscopy is undertaken in patients with dyspepsia, gastric biopsies should be taken to evaluate for H. pylori infection. Infected patients should be offered eradication therapy (Strong recommendation, high quality of evidence). Patients with typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) who do not have a history of PUD need not be tested for H. pylori infection. However, for those who are tested and found to be infected, treatment should be offered, acknowledging that effects on GERD symptoms are unpredictable (strong recommendation, high quality of evidence). In patients taking long-term low-dose aspirin, testing for H. pylori infection could be considered to reduce the risk of ulcer bleeding. Those who test positive should be offered eradication therapy (conditional recommendation, moderate quality of evidence). Patients initiating chronic treatment with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) should be tested for H. pylori infection (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence). Those who test positive should be offered eradication therapy. The benefits of testing and treating H. pylori in patients already taking NSAIDs remains unclear (conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence). Patients with unexplained iron deficiency (ID) anemia despite an appropriate evaluation should be tested for H. pylori infection. Those who test positive should be offered eradication therapy (conditional recommendation, high quality of evidence). Adults with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) should be tested for H. pylori infection. Those who test positive should be offered eradication therapy (conditional recommendation, very low quality of evidence). There is insufficient evidence to support routine testing and treating of H. pylori in asymptomatic individuals with a family history of gastric cancer or patients with lymphocytic gastritis, hyperplastic gastric polyps and hyperemesis gravidarum (no recommendation, very low quality of evidence). The ACG’s 2007 treatment guideline on the management of H. pylori infection (26) listed the following as established indications for diagnosis and treatment: Active PUD (gastric or duodenal). Confirmed history of PUD (not previously treated for H. pylori). Gastric MALT lymphoma (low grade). After endoscopic resection of EGC. The current guideline extends the list of potential indications to test patients for H. pylori infection. There are varying levels of evidence in support of the different potential indications for testing that are listed below. For some of these, the decision to test an individual patient for H. pylori will be influenced by clinical judgment and considerations of a patient’s general medical condition. Not all of these potential indications are given a definite recommendation, so that clinicians may exercise their judgment for individual patients. There is no justification in North America for universal or population-based screening. PUD The evidence in support of the 2007 recommendation was substantive at that time and these broad recommendations are still pertinent. All patients with a new diagnosis or a past history of PUD should be tested for H. pylori infection. Ideally, tests which identify active infection such as a urea breath test, fecal antigen test, or when endoscopy is performed, mucosal biopsy-based testing should be utilized. Because of the higher pretest probability of infection, patients with documented PUD represent a rare group, where it is acceptable to utilize an IgG H. pylori antibody test. In most other circumstances where the pretest probability of infection is lower, tests which identify active disease are preferred over antibody testing. Patients with a history of PUD who have previously been treated for H. pylori infection should undergo eradication testing with a urea breath test or fecal antigen test. Patients with evidence of ongoing infection should be treated appropriately. Gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma The term “MALT lymphoma” has largely been supplanted by “marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type”. Identification of this neoplasm remains a key indication to test for, and to eradicate, H. pylori infection. A review published in 2009 identified and summarized six prospective cohort studies of treatment for H. pylori infection in patients with gastric MALT lymphoma (also referred to as “localized B-cell lymphoma of the stomach”) but found no systematic reviews or randomized controlled trials (27). Tumor regression was reported in 60–93% of patients after eradication of H. pylori infection, but response was inconsistent, with some patients showing a delayed response and some showing tumor relapse within a year of treatment. More recent studies have confirmed these observations. In a Japanese series, 77% out of 420 patients treated for H. pylori infection showed either complete histological response or probable minimal residual disease (the investigators’ definition of response), although 10 (3%) responders relapsed in a mean of 6.5 years (28). Among infected patients who did not respond to eradication treatment, there was progression of the disease in 27%. Among 120 patients in Germany followed for a median of 122 months, there was initial complete remission in 80% following treatment of H. pylori infection (29). Out of these, 3% had macroscopic recurrence of disease within 24 months, and another 17% had histological residual disease found after a median of 48 months. A recent review has suggested that treatment of H. pylori infection may also be beneficial for patients diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the stomach (30). Early gastric cancer Three recent meta-analyses have each found that the incidence of metachronous gastric cancer following the endoscopic resection of a gastric neoplasm was reduced by the eradication of H. pylori infection (31, 32, 33). The most inclusive analysis by Yoon et al. (33) included 13 studies (three prospective and 10 retrospective) comprising 6687 patients. The pooled OR of gastric cancer in patients successfully cured of H. pylori was 0.42 (95% CI 0.32–0.56); in a subgroup analysis of the three prospective studies, the OR was 0.39 (95% CI 0.20–0.75) (33, 34). The other two meta-analyses yielded similar results (31, 32). Most recently, a meta-analysis comprising 24 studies (22 out of which were conducted in Asia) confirmed a lower rate of metachronous EGC following treatment of H. pylori infection; the incidence rate ratio was 0.54 (95% CI 0.46–0.65) (34). Dyspepsia (uninvestigated) Dyspepsia (defined as pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen) is highly prevalent in North America and elsewhere. In North America, most patients with dyspepsia will not have serious underlying, organic disease to explain their symptoms. That is, most will be found to have functional dyspepsia (FD), which is discussed elsewhere in this guideline. The ACG’s 2007 guideline on H. pylori management (26) included uninvestigated dyspepsia (depending upon H. pylori prevalence) in its list of established indications for diagnosis and treatment of H. pylori infection. The test and treat strategy for H. pylori infection was endorsed for patients under age 55 with dyspeptic symptoms and without alarm features. In the UK, the Bristol Helicobacter Project randomized 1517 H. pylori-positive adults to treatment for H. pylori infection or placebo and followed them prospectively (35). Among those treated for the infection, of whom over 90% achieved successful eradication, there was a small but statistically significant (P<0.05) reduction in subsequent consultations at the primary care level for dyspeptic complaints. The Cochrane Collaboration’s review on initial management strategies for dyspepsia was published in 2005 (36). As of early 2016, it had not been updated. A “test and treat” strategy for H. pylori had been found to be more effective than empirical acid suppression with either a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) or H2-receptor antagonist in managing dyspepsia (relative risk (RR) 0.59; 95% CI 0.42–0.83). This conclusion differs from an individual patient data meta-analysis which included three RCTs of 1537 patients randomized to the “test and treat” strategy or empirical acid suppression for the management of dyspepsia in the primary care setting (37). Although there was no significant difference between the groups in terms of symptom cure at 12 months, there was a trend for reduced overall costs in those assigned to “test and treat”. An individual patient data meta-analysis included five RCTs of 1924 patients randomized to “test and treat” or to prompt upper endoscopy for the evaluation of dyspeptic symptoms (38). After 1 year, the RR of remaining symptomatic was 0.95 (95% CI 0.92–0.99) in favor of prompt endoscopy. However, costs were lower with the “test and treat” approach. Prompt endoscopy for all patients with dyspepsia is neither feasible nor cost-effective. Functional dyspepsia A Cochrane systematic review published in 2006 concluded that there was a small but statistically significant benefit of treating H. pylori infection in patients with FD (39). In 17 RCTs comprising over 3500 patients, the RR reduction seen with treatment of H. pylori infection was 10% (95% CI 6–14%) and the number needed to treat (NNT) to cure one patient with FD was 14 (95% CI 10–25) (39). A subsequent update of that Cochrane review included 21 trials comprising 4331 patients (40). Most trials assessed patients’ symptoms 12 months after treatment. This study validated the NNT of 14 but with a narrower 95% CI (10–20). The Rome IV criteria have suggested subgrouping patients with FD into two groups, epigastric pain syndrome (epigastric pain and/or burning) or post-prandial distress syndrome (meal-related early satiation and/or fullness), while acknowledging that there may be considerable overlap between these (41). Although treatment trials have not utilized these newest criteria, improvement has been shown for patients with either predominant epigastric pain or predominant dysmotility-type symptoms following eradication of H. pylori infection (40). Since some FD patients with H. pylori infection experience durable benefit following eradication therapy, we recommend testing for, and treating, H. pylori in patients with FD. This aligns with a recent guideline by the American Gastroenterological Association, which recommends collecting biopsies of normal-appearing gastric mucosa to test for H. pylori when performing endoscopy in patients with dyspeptic symptoms (42). At the time of preparing this guideline, the ACG and the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology were in the process of preparing a joint guideline on management of uninvestigated dyspepsia and FD (43). Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) There is no proven causal association between H. pylori infection and GERD. On a geographical basis, there is a negative association between the prevalence of H. pylori infection and the prevalence and severity of GERD (44). Barrett’s esophagus is more common among individuals who are not infected with H. pylori (45). The risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus is lower among those with H. pylori infection (45). The ACG’s 2007 guideline on H. pylori (26) reviewed the evidence for any change in GERD symptoms or severity following eradication of H. pylori infection. In North Americans who acquire H. pylori infection, the most likely phenotype is antral-predominant gastritis, hypergastrinemia, parietal cell hyperplasia, and increased gastric acid secretion. Such individuals who also have GERD may experience an improvement in GERD symptoms following eradication of H. pylori infection as gastric acid secretion slowly decreases in association with resolution of antral-predominant gastritis and hypergastrinemia (46). In a post hoc analysis of eight RCTs of the treatment of H. pylori infection in duodenal ulcer patients, there was no significant difference in the development of erosive esophagitis or GERD symptoms between those with successful and failed eradication (47). Among patients with pre-existing GERD, there was a worsening of symptoms in 7% of those cured of the infection and in 15% of those with persistent infection (OR=0.47; 95% CI 0.24–0.91; P=0.02). It is theoretically possible, however, that patients with corpus-predominant gastritis may experience onset or worsening of GERD symptoms following H. pylori eradication as a consequence of restitution of parietal cell mass and increased gastric acid secretion. However, this scenario should be relatively uncommon in North America. In a community-based study from the UK (the Bristol Helicobacter Project), treatment for H. pylori infection was not associated with an increase in the prevalence of heartburn or other reflux symptoms (48). Similarly, treatment for H. pylori infection did not improve reflux symptoms in patients with pre-existing symptoms. A systematic review of 27 published studies concluded that eradication of H. pylori infection from patients with duodenal ulcer did not predispose to the development of GERD (49) or worsen symptoms in patients with established GERD (49). Others have reported that cure of H. pylori infection in patients with erosive esophagitis before starting PPI therapy does not influence healing rates or symptom response (50, 51, 52). Therefore, based upon currently available evidence, there is no indication to test a patient with typical GERD symptoms for H. pylori infection unless that patient also has a history of PUD or dyspeptic symptoms. Patients with GERD who are tested for H. pylori infection for any reason and who are found to be positive should be offered treatment for the infection acknowledging that GERD symptoms are unlikely to improve. Long-term treatment with PPIs in H. pylori-positive individuals with corpus-predominant gastritis may promote the development of atrophic gastritis (53, 54). Although eradication of the infection before initiating PPI therapy may prevent the progression to atrophic gastritis (55), the clinical relevance of this is unclear. Low-dose aspirin use Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid, ASA) is frequently recommended for patients with cardiovascular risk factors or following a major cardiovascular event (56). ASA use increases the risk of upper GI tract ulceration. H. pylori infection is a recognized risk factor for the development of ulcers and for ulcer bleeding during low-dose ASA treatment (57, 58). In a study conducted in Canada, Australia, the UK and Spain, the prevalence of peptic ulcer at endoscopy among 187 middle-aged and elderly patients taking ASA in doses of 75–325 mg daily was 10.7% (95% CI 6.3–15.1%) (59). H. pylori infection was a significant risk factor for ASA-related duodenal ulcer (OR=18.5; 95% CI 2.3–149.4) but not for gastric ulcer (OR=2.3; 95% CI 0.7–7.8). In a study from Hong Kong, patients with an episode of peptic ulcer bleeding while on low-dose ASA were studied according to H. pylori status (60). Those who were cured of H. pylori infection and subsequently re-started on ASA, had a similar rate of recurrent ulcer bleeding as in a previously ASA-naive cohort without bleeding who were started on low-dose ASA. Thus, eradication of H. pylori infection from patients with ASA-associated ulcer bleeding reduces the risk of recurrent bleeding. Regarding other anti-platelet agents, the 2010 expert consensus document jointly prepared by the ACG, the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association acknowledged that H. pylori infection was an established risk factor for upper GI bleeding among patients using thienopyridine anti-platelet agents (61) but made no specific recommendations concerning testing for, or treating, the infection in patients taking these medicines. However, testing for H. pylori will commonly be indicated in patients using these agents since most will also be taking ASA. In the absence of a prospective randomized study addressing H. pylori eradication in North American patients at increased risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes, we suggest testing for H. pylori when starting prophylactic low-dose aspirin, while acknowledging that the evidence base for this recommendation is weak. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use H. pylori infection is an independent risk factor for NSAID-induced ulcers and ulcer bleeding (62, 63). Eradication of H. pylori infection before starting NSAID treatment reduces the development of ulcers and risk of ulcer bleeding (64, 65). A 2005 meta-analysis of five RCTs suggested that eradication of H. pylori infection among patients taking NSAIDs was associated with a 57% reduction in the incidence of peptic ulcer (OR=0.43; 95% CI 0.20–0.93) (66). The benefits of H. pylori eradication were greatest in patients who were previously NSAID-naive. Eradication of H. pylori infection before starting NSAID therapy may be the single most cost-effective strategy for the primary prevention of NSAID-associated ulcers in adult patients (67). The benefit of H. pylori eradication in patients already taking NSAIDs is less clear (68). RCTs suggest that H. pylori eradication does not reduce the incidence of new peptic ulcers in chronic NSAID users (69) and that PPI therapy provides a more effective ulcer risk reduction strategy than H. pylori eradication in patients on chronic NSAIDs (66). The ACG’s most recent practice guideline on the prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications (63) concluded that H. pylori infection increases the risk of NSAID-related GI complications, that there would be at least a potential advantage of testing for the infection in patients requiring long-term NSAID therapy, and that the infection should be eradicated when identified. Iron deficiency anemia H. pylori infection has been associated with ID and iron deficiency anemia (IDA). In a meta-analysis of observational studies, the pooled ORs for ID and IDA in H. pylori-infected individuals were 1.4 (95% CI 1.2–1.6) and 2.0 (95% CI 1.5–2.9), respectively. A separate meta-analysis of 15 observational studies also found that IDA was more prevalent in H. pylori-infected individuals compared with H. pylori-negative controls (OR=2.2; 95% CI 1.5–3.2) (70). Adolescents with IDA have been reported to have a higher prevalence of H. pylori infection than non-anemic controls (71). H. pylori-infected adolescents and adults with IDA respond to oral iron therapy whether or not accompanied by treatment for H. pylori infection. However, the response to iron therapy in H. pylori-infected patients with IDA may be enhanced by the concomitant eradication of the infection (71, 72). A meta-analysis of 16 RCTs conducted among patients with IDA and H. pylori infection found statistically significant differences in favor of H. pylori eradication with oral iron over oral iron alone for increases in hemoglobin (Hgb), serum iron and serum ferritin (SF) levels (P<0.00001 for each) (73). In a separate meta-analysis of four interventional trials, the weighted mean difference in Hgb levels in favor of combined eradication treatment and oral iron vs. oral iron alone was 4.1 g/dl (95% CI −2.6–10.7); that for SF levels in five trials was 9.5 μg/l (95% CI −0.5–19.4) (70). A Cochrane systematic review is being conducted on the topic of the eradication of H. pylori infection for ID but its findings have not yet been reported (74). Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) There is evidence from small randomized and non-randomized trials for a sustained improvement in platelet counts after eradication of H. pylori infection in a proportion of adult patients with ITP (75, 76, 77). The evidence is less compelling for children with ITP (78). A systematic review of 25 studies (1555 adult patients), all of which included at least 15 patients, found that platelet counts in ITP patients tended to increase after H. pylori eradication (79). Among 696 evaluable patients, 43% achieved a complete response (defined as a platelet count ≥100 × 109/l), and an additional 50% had an overall response (defined as a platelet count ≥30 × 109/l and at least a doubling of the baseline platelet count). Response rates were lower in patients with a baseline platelet count of <30 × 109/l. In general, response rates were higher in regions with high background H. pylori prevalence and in patients with mild degrees of thrombocytopenia. In their practice guideline published in 2011 (80), the American Society of Hematology (ASH) suggested that “screening for H. pylori infection be considered in adults with ITP in whom eradication therapy would be used if testing is positive” (evidence grade 2C). The ASH also recommended that eradication therapy be administered to adults with ITP who were found to have H. pylori based on a test of active infection (evidence grade 1B). The ASH has recommended against testing children with ITP for H. pylori infection (80). Asymptomatic individuals and the risk of gastric cancer Evidence that eradication of H. pylori infection reverses the gastric premalignant changes of gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia is conflicting. A meta-analysis of 12 studies (2658 patients) published up until 2009 reported that eradication was associated with a significant reduction in atrophic gastritis in the corpus (P=0.006) but not in the antrum (P=0.06); there was no evidence for a significant effect on intestinal metaplasia in either the corpus (P=0.42) or antrum (P=0.76) (81). A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis examined six RCTs (five of which were in Asian populations) that studied the effects of H. pylori eradication treatment against either placebo or no treatment on the subsequent development of gastric cancer among asymptomatic and otherwise healthy-infected adults (82). All trials followed subjects for at least 2 years. The quality of evidence was assessed as moderate. The subsequent incidence of gastric cancer was 1.6% among 3294 treated individuals and 2.4% among 3203 untreated controls (RR=0.66; 95% CI 0.46–0.95). The overall NNT was 124 (95% CI 78–843). However, assuming that the benefits of H. pylori eradication persist for life, the NNT could be as low as 15 among Chinese men. Since the lifetime risk of gastric cancer is lower in the United States, the corresponding NNT to prevent one case here would be 95 for men and 163 for women. A recent meta-analysis of 24 studies, 22 of which were conducted in Asia, showed that treatment of H. pylori infection in asymptomatic, infected adults led to a reduced incidence of gastric cancer. The greatest benefit was seen in people living in regions with the highest incidence of gastric cancer; reported RRs for regions of low, intermediate and high incidence of gastric cancer were, respectively, 0.80, 0.49, and 0.45 (34). Other gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal disorders Associations have been proposed between H. pylori infection and numerous other disorders (83). In most cases, biological plausibility and the level of evidence to support a causal association has been weak to non-existent. Thus, no formal recommendation can be offered. Controlled trials have suggested a benefit of H. pylori eradication in healing lymphocytic gastritis (84) and inducing regression of hyperplastic gastric polyps (85). There is some data to suggest a weak association between H. pylori infection and hyperammonemia and hepatic encephalopathy (HE) in patients with cirrhosis (86); trials evaluating H. pylori therapy in patients with HE have yielded conflicting results. In a meta-analysis of observational studies, the prevalence of H. pylori infection in pregnant women with hyperemesis gravidarum was higher than in matched controls (87). An association between H. pylori infection and major cardiovascular events including myocardial infarction and stroke has been postulated. However, evidence is of low quality and insufficient to establish causality (88). A Cochrane systematic review of H. pylori infection in Parkinson’s disease (89) identified three clinical trials and concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support screening for H. pylori infection in this population. Limited evidence suggests that symptoms of Parkinson’s may improve with H. pylori eradication, perhaps due to increases in the absorption and bioavailability of levodopa. Further randomized, controlled trials were encouraged. An evidence-based review of treating H. pylori infection in patients with urticaria found only low-quality evidence (90); nine out of 10 trials identified showed no benefit from H. pylori eradication. A meta-analysis has reported higher levels of glycosylated hemoglobin in H. pylori-positive patients with type 1 diabetes compared with non-infected patients (91). However, glycemic control did not improve in the short term following eradication of H. pylori. An inverse association has been reported between the prevalence of H. pylori infection and obesity (92). There may also be a weak inverse association between H. pylori infection and allergic or atopic disorders (93, 94) including eosinophilic esophagitis (95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100) as well as celiac disease (101) and inflammatory bowel disease (102). Question 3: What Are Evidence-Based First-Line Treatment Strategies for Providers in North America? Recommendations Patients should be asked about any previous antibiotic exposure(s) and this information should be taken into consideration when choosing an H. pylori treatment regimen (conditional recommendation, moderate quality of evidence). Clarithromycin triple therapy consisting of a PPI, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin or metronidazole for 14 days remains a recommended treatment option in regions where H. pylori clarithromycin resistance is known to be <15% and in patients with no previous history of macrolide exposure for any reason (conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence (for duration: moderate quality of evidence)). Bismuth quadruple therapy consisting of a PPI, bismuth, tetracycline, and a nitroimidazole for 10–14 days is a recommended first-line treatment option. Bismuth quadruple therapy is particularly attractive in patients with any previous macrolide exposure or who are allergic to penicillin (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence). Concomitant therapy consisting of a PPI, clarithromycin, amoxicillin and a nitroimidazole for 10–14 days is a recommended first-line treatment option (Strong recommendation, low quality of evidence (for duration: very low quality of evidence)). Sequential therapy consisting of a PPI and amoxicillin for 5–7 days followed by a PPI, clarithromycin, and a nitroimidazole for 5–7 days is a suggested first-line treatment option (conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence (for duration: very low quality of evidence). Hybrid therapy consisting of a PPI and amoxicillin for 7 days followed by a PPI, amoxicillin, clarithromycin and a nitroimidazole for 7 days is a suggested first-line treatment option (conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence (For duration: very low quality of evidence)). Levofloxacin triple therapy consisting of a PPI, levofloxacin, and amoxicillin for 10–14 days is a suggested first-line treatment option (conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence (for duration: very low quality of evidence)). Fluoroquinolone sequential therapy consisting of a PPI and amoxicillin for 5–7 days followed by a PPI, fluoroquinolone, and nitroimidazole for 5–7 days is a suggested first-line treatment option (conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence (For duration: very low quality of evidence)). H. pylori is an infectious disease that is typically treated with combinations of 2–3 antibiotics along with a PPI, taken concomitantly or sequentially, for periods ranging from 3 to 14 days. In clinical practice, the initial course of eradication therapy, heretofore referred to as “first-line” therapy, generally offers the greatest likelihood of treatment success. Thus, careful attention to the selection of the most appropriate first-line eradication therapy for an individual patient is essential. There is no treatment regimen which guarantees cure of H. pylori infection in 100% of patients. Indeed, there are currently few, if any regimens which consistently achieve eradication rates exceeding 90% (103). In developing this guideline for North America, we conducted comprehensive literature searches to identify randomized, controlled trials which have evaluated the efficacy of treatment regiments in the United States and Canada. Wherever possible, we have tried to highlight these data and use them to develop treatment recommendations. Unfortunately, although H. pylori was the subject of many randomized, controlled trials conducted in North America during the first decade of this century, the number of treatment trials assessing modern regimens is modest to non-existent. As such, we were forced to rely upon clinical trial data generated in other parts of the world when considering a number of regimens. Development of this guideline has made clear the need for clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of modern treatment regimens and organized efforts to monitor H. pylori antibiotic resistance in North America. To provide readers a sense of the author’s preferences, we have taken the liberty of utilizing the words “recommended” vs. “suggested” in the italicized statements that address each of the treatment regimens. A listing of available first-line treatment options can be found in Table 2. A schema to assist providers to choose the best therapy for an individual patient can be found in Figure 1. Table 2. Recommended first-line therapies for H pylori infection Regimen Drugs (doses) Dosing frequency Duration (days) FDA approval Clarithromycin triple PPI (standard or double dose) BID 14 Yesa Clarithromycin (500 mg) Amoxicillin (1 grm) or Metronidazole (500 mg TID) Bismuth quadruple PPI (standard dose) BID 10–14 Nob Bismuth subcitrate (120–300 mg) or subsalicylate (300 mg) QID Tetracycline (500 mg) QID Metronidazole (250–500 mg) QID (250) TID to QID (500) Concomitant PPI (standard dose) BID 10–14 No Clarithromycin (500 mg) Amoxicillin (1 grm) Nitroimidazole (500 mg)c Sequential PPI (standard dose)+Amoxicillin (1 grm) BID 5–7 No PPI, Clarithromycin (500 mg)+Nitroimidazole (500 mg)c BID 5–7 Hybrid PPI (standard dose)+Amox (1 grm) BID 7 No PPI, Amox, Clarithromycin (500 mg), Nitroimidazole (500 mg)c BID 7 Levofloxacin triple PPI (standard dose) BID 10–14 No Levofloxacin (500 mg) QD Amox (1 grm) BID Levofloxacin sequential PPI (standard or double dose)+Amox (1 grm) BID 5–7 No PPI, Amox, Levofloxacin (500 mg QD), Nitroimidazole (500 mg)c BID 5–7 LOAD Levofloxacin (250 mg) QD 7–10 No PPI (double dose) QD Nitazoxanide (500 mg) BID Doxycycline (100 mg) QD BID, twice daily; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; TID, three times daily; QD, once daily; QID, four times daily. a Several PPI, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin combinations have achieved FDA approval. PPI, clarithromycin and metronidazole is not an FDA-approved treatment regimen. b PPI, bismuth, tetracycline, and metronidazole prescribed separately is not an FDA-approved treatment regimen. However, Pylera, a combination product containing bismuth subcitrate, tetracycline, and metronidazole combined with a PPI for 10 days is an FDA-approved treatment regimen. c Metronidazole or tinidazole. Figure 1. Selection of a first-line H. pylori treatment regimen. With very few exceptions, the most common adverse events associated with antibiotics used to treat H. pylori infection are gastrointestinal in origin (for example: nausea, dysgeusia, dyspepsia/abdominal pain, diarrhea). As such, we have not listed adverse events for most of the therapies. Where unusual adverse events can occur with a specific therapy, we have tried to point that out. Clarithromycin triple therapy The previous ACG guideline from 2007 recommended 14 days of treatment with a PPI, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin (clarithromycin-based triple therapy) or—in patients with an allergy to penicillin—metronidazole as an alternative to amoxicillin. At that time, eradication rates for clarithromycin triple therapy were reported to be 70–85% and were highly influenced by the underlying rate of clarithromycin resistance (26). However, there has been growing concern regarding the efficacy of clarithromycin triple therapy. Key questions which were considered while preparing this document included the expected eradication rate of clarithromycin triple therapy in North America, the most appropriate duration of therapy, and whether eradication rates have been dropping over time. There are data from other parts of the world to suggest that eradication rates for clarithromycin triple therapy are below 80% (103). In preparing this updated guideline, we identified all randomized, controlled trials conducted in the United States or Canada which have assessed the efficacy of this regimen since 2000 (100, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119). Consistent with other meta-analyses, eradication rates with 7 or 10 days of clarithromycin triple therapy in studies from the US or Canada were indeed below 80%. Eradication rates with 14 days of triple therapy were higher, but only two study arms with 195 subjects were included. This finding is consistent with the most recent and most complete meta-analysis or the world’s literature on this topic which was published by the Cochrane Collaboration (120). For clarithromycin triple therapy, higher eradication rates were reported with 14 vs. 7 days of treatment (34 studies, RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.57–0.75; NNT 12, 95% CI 9–16), and with 14 vs. 10 days (10 studies, RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.52–0.91). Based upon the available data, when triple therapy is utilized in North America, it should be given for 14 days. The lack of recent RCT data on clarithromycin triple therapy makes it difficult to confidently report on temporal trends in eradication rates. To address this issue, we conducted a retrospective analysis of eradication rates for clarithromycin triple therapy at the University of Michigan from 2001–15. Data was divided into 5-year blocks and eradication rates for 10–14 days of triple therapy when given first-line were calculated. In 662 patients, the overall eradication rate was 79.5% (95% CI 77.2–82.4%) with no significant difference in eradication rates for the 3, 5-year blocks (Figure 2, unpublished data). Figure 2. Eradication rates with first-line clarithromycin triple therapy at the University of Michigan (2001–2015). The impact of clarithromycin resistance on the efficacy of clarithromycin triple therapy is well documented. A 2010 meta-analysis reported an eradication rate of 22% for clarithromycin-resistant H. pylori strains compared with 90% for clarithromycin-sensitive strains (121). As such, clarithromycin triple therapy should not be utilized in areas where the rate of clarithromycin resistance is known to be high. The Maastricht/Florence Consensus document published in 2012 recommended against using triple therapy when the rate of underlying clarithromycin resistance exceeds 15–20% (55). Although current large scale data on H. pylori antibiotic resistance in North America are unavailable, recent data from Houston suggest that clarithromycin resistance rates may now fall within that range (122). In the absence of local or even regional H. pylori antibiotic resistance data, it is very important to ask patients about previous exposure to antibiotics for any reason, particularly macrolides and fluoroquinolones, as this provides a proxy for underlying H. pylori antibiotic resistance (123, 124). A recent study confirmed an association between number of previous antibiotic exposures and an increasing risk for antibiotic resistance (125). Similarly, duration of previous macrolide therapy for greater than 2 weeks is also associated with a greater risk of treatment failure with clarithromycin triple therapy (126). Based upon the available data, we conclude that clarithromycin triple therapy consisting of a PPI, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin or metronidazole for 14 days remains a first-line treatment option in regions where H. pylori clarithromycin resistance is known to be low. In regions where clarithromycin resistance exceeds 15%, as may well be the case in many parts of North America, clarithromycin triple therapy should be avoided. All patients should be asked about previous macrolide exposure for any reason. In those with previous macrolide exposure, clarithromycin triple therapy should be avoided. Bismuth quadruple therapy The previous ACG guideline also endorsed the use of 10–14 days of bismuth quadruple therapy composed of a PPI or histamine-2 receptor antagonist, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline. There is very limited data on the efficacy or comparative effectiveness of bismuth quadruple therapy in North America. A literature search identified only two RCTs which included a bismuth quadruple therapy arm (n=172). The mean eradication rate with this regimen given for 10 days was 91% (95% CI; 81–98%). A meta-analysis of studies from around the world comparing clarithromycin triple and bismuth quadruple therapies suggested that the two treatments had similar efficacy, compliance, and tolerability (121). An updated meta-analysis, which included 12 RCTs and 2753 patients, reported intention-to-treat (ITT) eradication rates of 77.6% with bismuth quadruple therapy vs. 68.9% with clarithromycin triple therapy (risk difference=0.06, 95% CI; −0.01 to 0.13). There was significant heterogeneity in the data set, in part attributable to differences in trea

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

onto Allergy (and clinical immunology) September 18, 2018 12:05 PM

|

No comment yet.

Sign up to comment

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...