Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

March 31, 2015 6:14 AM

|

Author Summary Plants possess multi-layered immune recognition systems. Early in the infection process, plants use receptor proteins to recognize pathogen molecules. Some of these receptors are present in only in a subset of plant species. Transfer of these taxonomically restricted immune receptors between plant species by genetic engineering is a promising approach for boosting the plant immune system. Here we show the successful transfer of an immune receptor from a species in the mustard family, called EFR, to rice. Rice plants expressing EFR are able to sense the bacterial ligand of EFR and elicit an immune response. We show that the EFR receptor is able to use components of the rice immune signaling pathway for its function. Under laboratory conditions, this leads to an enhanced resistance response to two weakly virulent isolates of an economically important bacterial disease of rice.

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

March 25, 2015 7:13 AM

|

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

March 20, 2015 7:44 AM

|

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

March 17, 2015 6:04 AM

|

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

March 9, 2015 7:05 AM

|

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

March 6, 2015 4:17 AM

|

Plant innate immunity depends on the function of a large number of intracellular immune receptor proteins, the majority of which are structurally similar to mammalian nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor (NLR) proteins. CHILLING SENSITIVE 3 (CHS3) encodes an atypical Toll/Interleukin 1 Receptor (TIR)-type NLR protein with an additional Lin-11, Isl-1 and Mec-3 (LIM) domain at its C-terminus. The gain-of-function mutant allele chs3-2D exhibits severe dwarfism and constitutively activated defense responses, including enhanced resistance to virulent pathogens, high defence marker gene expression, and salicylic acid accumulation. To search for novel regulators involved in CHS3-mediated immune signaling, we conducted suppressor screens in the chs3-2D and chs3-2D pad4-1 genetic backgrounds. Alleles of sag101 and eds1-90 were isolated as complete suppressors of chs3-2D, and alleles of sgt1b were isolated as partial suppressors of chs3-2D pad4-1. These mutants suggest that SAG101, EDS1-90, and SGT1b are all positive regulators of CHS3-mediated defense signaling. Additionally, the TIR-type NLR-encoding CSA1 locus located genomically adjacent to CHS3 was found to be fully required for chs3-2D-mediated autoimmunity. CSA1 is located 3.9[emsp14]kb upstream of CHS3 and is transcribed in the opposite direction. Altogether, these data illustrate the distinct genetic requirements for CHS3-mediated defense signaling.

|

Rescooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

from Publications

March 2, 2015 9:36 AM

|

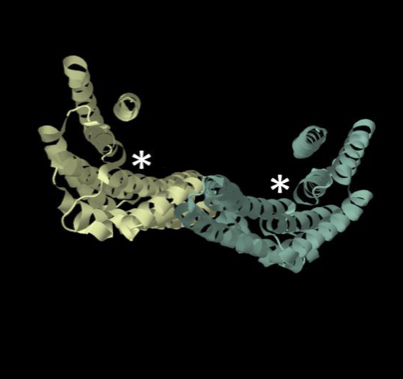

Our conceptual and mechanistic understanding of how plant nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR or NB-LRR) proteins perceive pathogens continues to advance. NLRs are intracellular multidomain proteins that recognize pathogen-derived effectors either directly or indirectly (Jones and Dangl, 2006; van der Hoorn and Kamoun, 2008; Dodds and Rathjen, 2010; Cesari et al., 2014). In the direct model, the NLR protein binds a pathogen effector or serves as a substrate for the effector’s enzymatic activity. In the indirect model, the NLR recognizes modifications of additional host protein(s) targeted by the effector. Such intermediate host protein(s) are often called effector targets (ETs). However, given that effectors can act on multiple host targets, the specific protein that mediates recognition by the NLR may not be the effector’s operative target and may have evolved to function as a decoy dedicated to pathogen detection. This “decoy” model contrasts with the “guard” model in which the NLR perceives the effector via its action on its operative target (van der Hoorn and Kamoun, 2008).

In a recent article, Cesari et al. (2014) elegantly synthesized the literature to propose a novel model of how NLRs recognise effectors termed the “integrated decoy” hypothesis. Based on new data from several pathosystems, it appears that some NLRs recognize pathogen effectors through extraneous domains that have evolved by duplication of an ET followed by fusion into the NLR. This NLR-integrated domain mimics the effector binding/substrate property of the original ET to enable pathogen detection. In addition, these “receptor” or “sensor” NLRs typically partner with NLR proteins with a classic architecture that function as signalling partners required for the resistance response (Eitas and Dangl, 2010; Cesari et al., 2013; Cesari et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2014).

Here, we expand on the Cesari et al. (2014) model and introduce the possibility that NLR-integrated domains do not have to be decoys (as in defective mimics) of the effector’s operative target. Indeed, in addition to binding effectors or serving as their substrates, operative targets carry a biochemical activity that is modulated by the effector. The perturbation of this activity by the effector leads to effector-triggered susceptibility, an activity often related to immunity (Boller and He, 2009; Dodds and Rathjen, 2010; Win et al., 2012). Clearly NLR-integrated domains must retain the “sensor” activity of the ancestral ET, but they could also retain their biochemical activity, continuing to function in the effector-targeted pathway even as an extraneous domain within a classic NLR architecture. At present, this possibility cannot be discounted given that the biochemical activities of the ancestral ETs and their NLR-integrated counterparts are generally unknown. Additionally, when NLR-fusions occurred recently, there may not have been enough time for the integrated ET to lose its original function and evolve into a decoy. We therefore propose to refer to the extraneous domains of classic NLR proteins described by Cesari et al. (2014) as sensor domains (SD), a term that is agnostic to any potential biochemical activities of the integrated module.

How to test whether or not SDs are decoys? We propose a straightforward genetic test that can reject the decoy hypothesis. Isogenic plants either carrying or lacking the NLR-SD can be challenged with a pathogen strain that lacks the matching avirulence effector (Figure 1). There are several possible outcomes. If the NLR-SD isogenic lines do not differ in their response to the pathogen without the matching effector, the result is inconclusive and the null decoy hypothesis cannot be rejected. If the presence of NLR-SD without the known matching effector shows higher levels of resistance, and there are no signs of typical effector-triggered immunity, then the SD is likely to have retained the ET biochemical activity and contributes to basal immunity in a manner analogous to the ancestral ET. An even more interesting result would be if in the absence of the matching effector, the NLR-SD line is more susceptible as has been shown for several ETs (van Schie and Takken, 2014). In this scenario, another (unrecognized) effector might still be targeting the original biochemical activity of the SD domain. It would be conceptually fascinating if an NLR that functions as a resistance (R) gene against certain strains of a pathogen becomes a susceptibility (S) gene when exposed to other strains. Once again, this concept emphasizes how the outcome of plant-pathogen interactions is so critically dependent on the genotypes of the interacting organisms – a gene that has a certain impact in a particular genetic combination can have the exact opposite effect in another (Jones and Dangl, 2006; van der Hoorn and Kamoun, 2008; Dodds and Rathjen, 2010; Win et al., 2012).

Our goal is not to engage in an exercise in semantics. However, we wish to avoid conceptually restrictive terminology and urge the plant-microbe interactions community to test a rich spectrum of models and hypotheses. The proposed sensor domain terminology would accommodate this breadth of ideas. Ultimately, it may very well turn out that the majority, if not all, of the NLR integrated domains have lost their biochemical activities and have evolved into decoys. Also, it is possible that the sensor domain has already evolved into a decoy prior to recombination into a NLR. Nonetheless, further genetic and biochemical experiments are required to determine whether sensor domains of NLR-SDs are decoys or biochemically functional duplicates of their ancestral ETs.

Via Kamoun Lab @ TSL

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

March 2, 2015 6:56 AM

|

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

January 29, 2015 4:57 AM

|

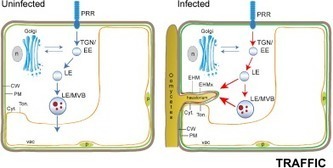

Pests and diseases cause significant agricultural losses. Plants recognize pathogen-derived molecules via plasma membrane-localized immune receptors (called pattern recognition receptors or PRRs), resulting in pathogen resistance. In recent years, the transfer of PRRs across plant species has emerged as a promising biotechnological approach to improve crop disease resistance. Successful transfers of PRRs suggest that immune signaling components are conserved across plant species. In this study, we demonstrate that the PRR XA21 from the monocot plant rice is functional in the dicot plant Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis) and that it confers quantitatively enhanced resistance to bacteria. Furthermore, we show that the rice XA21 and the Arabidopsis EFR, which are evolutionary-distant but phylogenetically closely related, recruit similar signaling components for their function, revealing an overall conservation of immune pathways across monocots and dicots. These findings demonstrate evolutionary conservation of downstream signaling from PRRs and indicate that transfer of PRRs is possible between different plant families, but also between monocots and dicots.

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

January 16, 2015 4:15 AM

|

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

December 8, 2014 5:30 AM

|

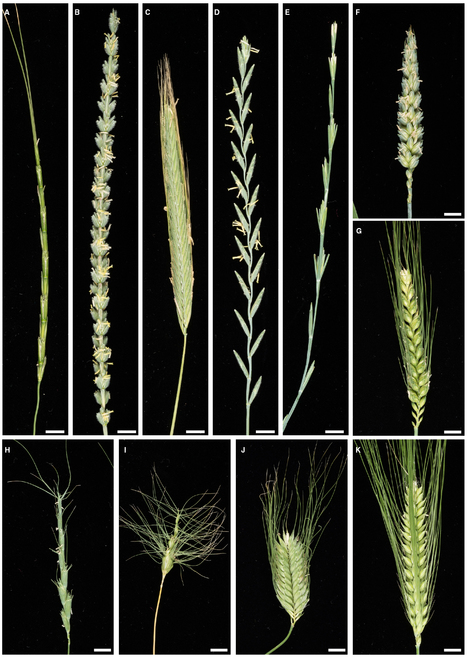

The domestication of wheat in the Fertile Crescent 10,000 years ago led to a genetic bottleneck. Modern agriculture has further narrowed the genetic base by introducing extreme levels of uniformity...

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

November 29, 2014 5:46 AM

|

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

November 14, 2014 5:48 AM

|

|

|

Rescooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

from Plants and Microbes

March 31, 2015 4:18 AM

|

Potato late blight, caused by the destructive Irish famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans, is a major threat to global food security1,2. All late blight resistance genes identified to date belong to the coiled-coil, nucleotide-binding, leucine-rich repeat class of intracellular immune receptors3. However, virulent races of the pathogen quickly evolved to evade recognition by these cytoplasmic immune receptors4. Here we demonstrate that the receptor-like protein ELR (elicitin response) from the wild potato Solanum microdontum mediates extracellular recognition of the elicitin domain, a molecular pattern that is conserved in Phytophthora species. ELR associates with the immune co-receptor BAK1/SERK3 and mediates broad-spectrum recognition of elicitin proteins from several Phytophthora species, including four diverse elicitins from P. infestans. Transfer of ELR into cultivated potato resulted in enhanced resistance to P. infestans. Pyramiding cell surface pattern recognition receptors with intracellular immune receptors could maximize the potential of generating a broader and potentially more durable resistance to this devastating plant pathogen.

Via Kamoun Lab @ TSL

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

March 24, 2015 5:39 AM

|

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

March 19, 2015 7:41 AM

|

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

March 12, 2015 5:48 AM

|

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

March 6, 2015 3:09 PM

|

|

Rescooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

from Publications

March 3, 2015 5:59 AM

|

Intracellular immune receptors of the nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NB-LRR or NLR) proteins often function in pairs, with "helper" proteins required for the activity of "sensors" that mediate pathogen recognition. The NLR helper NRC1 (NB-LRR protein required for HR-associated cell death 1) has been described as a signalling hub required for the cell death mediated by both cell surface and intracellular immune receptors in the model plant Nicotiana benthamiana. However, this work predates the availability of the N. benthamiana genome and whether NRC1 is indeed required for the reported phenotypes has not been confirmed. Here, we investigated the NRC family of solanaceous plants using a combination of genome annotation, phylogenetics, gene silencing and genetic complementation experiments. We discovered that a paralog of NRC1, we termed NRC3, is required for the hypersensitive cell death triggered by the disease resistance protein Pto but not Rx and Mi-1.2. NRC3 may also contribute to the hypersensitive cell death triggered by the receptor-like protein Cf-4. Our results highlight the importance of applying genetic complementation to validate gene function in RNA silencing experiments.

Via Kamoun Lab @ TSL

|

Rescooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

from Plant Pathogenomics

March 2, 2015 6:59 AM

|

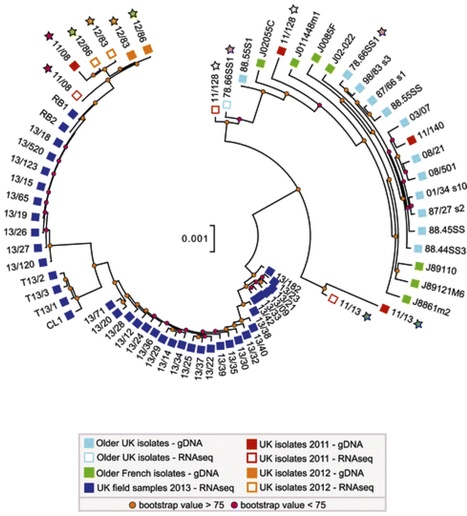

Background Emerging and re-emerging pathogens imperil public health and global food security. Responding to these threats requires improved surveillance and diagnostic systems. Despite their potential, genomic tools have not been readily applied to emerging or re-emerging plant pathogens such as the wheat yellow (stripe) rust pathogen Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici (PST). This is due largely to the obligate parasitic nature of PST, as culturing PST isolates for DNA extraction remains slow and tedious. Results To counteract the limitations associated with culturing PST, we developed and applied a field pathogenomics approach by transcriptome sequencing infected wheat leaves collected from the field in 2013. This enabled us to rapidly gain insights into this emerging pathogen population. We found that the PST population across the United Kingdom, UK, underwent a major shift in recent years. Population genetic structure analyses revealed four distinct lineages that correlated to the phenotypic groups determined through traditional pathology-based virulence assays. Furthermore, the genetic diversity between members of a single population cluster for all 2013 PST field samples was much higher than that displayed by historical UK isolates, revealing a more-diverse population of PST. Conclusions Our field pathogenomics approach uncovered a dramatic shift in the PST population in the UK, likely due to a recent introduction of a diverse set of exotic PST lineages. The methodology described herein accelerates genetic analysis of pathogen populations and circumvents the difficulties associated with obligate plant pathogens. In principle, this strategy can be widely applied to a variety of plant pathogens.

Via Kamoun Lab @ TSL

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

February 5, 2015 7:23 AM

|

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

January 16, 2015 4:30 AM

|

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

January 5, 2015 9:26 AM

|

|

Rescooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

from Publications

November 29, 2014 5:49 AM

|

• Cas9 is an RNA-guided DNA endonuclease innate to prokaryotic immune systems.

• CRISPR/Cas9 has recently emerged as a powerful genome editing tool.

• CRISPR/Cas9 has been successfully applied in many organisms, including model and crop plants.

• CRISPR/Cas9 is a cheap, robust and easy to implement technology. CRISPR/Cas9 is a rapidly developing genome editing technology that has been successfully applied in many organisms, including model and crop plants. Cas9, an RNA-guided DNA endonuclease, can be targeted to specific genomic sequences by engineering a separately encoded guide RNA with which it forms a complex. As only a short RNA sequence must be synthesized to confer recognition of a new target, CRISPR/Cas9 is a relatively cheap and easy to implement technology that has proven to be extremely versatile. Remarkably, in some plant species, homozygous knockout mutants can be produced in a single generation. Together with other sequence-specific nucleases, CRISPR/Cas9 is a game-changing technology that is poised to revolutionise basic research and plant breeding.

Via Kamoun Lab @ TSL

|

Scooped by

The Sainsbury Lab

November 22, 2014 4:43 AM

|

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...