Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

Last week Google sent out a notice reminding domain administrators that the end of the classic version of Google Sites is near. That prompted me to publish directions for transition from the classic version of Google Sites to the current version. I also shared a set of tutorials for building your first website with the current version of Google Sites. Once you've made the switch to the current version of Google Sites, you might want to go beyond the basics to add some interesting features to your site to make it a one-stop shop for all of your students' and parents' needs. Here are some things you can do to enhance your Google Site with additional features.

Via Elizabeth E Charles

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from blended learning

April 11, 2021 12:48 PM

|

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Edumorfosis.Work

April 11, 2021 12:37 PM

|

When the coronavirus pandemic took hold in early 2020, organizations across the globe had to quickly transition their employees to a remote work environment.

Roughly a year later, full-scale telework is still a reality for many organizations, especially so in the United States. Research from Mursion, Inc., a virtual reality training platform, found that most companies will stay in a remote or hybrid work environment, as just 9% of managers and 13% of employees plan to go back to the office full-time in the next six months.

Teleperformance, a customer experience management company, recently announced a shift to a hybrid work model across its global operations, a decision based on its telework success during the pandemic.

“Work from anywhere is not a pandemic play,” said Jose Guereque, executive vice president of infrastructure and chief information officer at Teleperformance. “We will keep the hybrid scheme forever as our permanent model.”

Via Edumorfosis

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Educational Technology News

March 30, 2021 4:00 PM

|

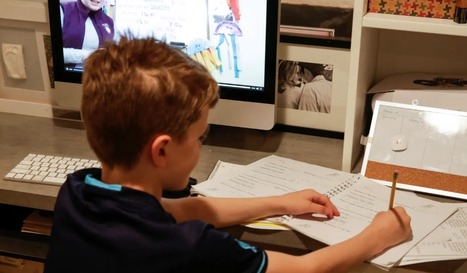

"Could greater public approval of homeschooling be an unexpected result of the pandemic’s forced experiment in remote online learning? Two surveys make it look that way."

Via EDTECH@UTRGV

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Online Marketing Tools

February 27, 2021 3:16 AM

|

By their very nature, pandemics shake the systems of society, and that is certainly true for the global educational system right now. Institutions have had to adjust their entire structures, and fo…

Via Online Marketing

The printing press and social media democratized communication in their respective times. They both turned the order of things on its head — for good, for ill, and forever. The printing press and social media democratized communication in their respective times. They both turned the order of things on its head — for good, for ill, and forever. CLAY S. JENKINSON, EDITOR-AT-LARGE | FEBRUARY 19, 2021 You can listen to the companion audio version of this and other essays in the series using the player below or on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Stitcher or Audible.

The Gutenberg Revolution To put it in a nutshell. No Gutenberg, no Luther. No Luther, no Reformation. At one point, Luther (1483-1546) was publishing a book (more like a pamphlet) every three or four weeks. The advent of moveable type and the printing press (ca. 1440) made it possible for an obscure monk’s critique of late medieval Catholicism to travel all over Europe. The printing press made it relatively easy to disseminate the Bible, particularly the New Testament and the Psalms, more widely than ever before — by magnitudes. RELATED A Lesson from Jefferson on How the Nation Can Heal The Double Edge of Our Digital Revolution It is no coincidence that just at that time Luther published his Bible in German (1522-1534) — thus essentially inventing the modern German language — and Erasmus of Rotterdam produced the first printed New Testament in Greek in 1516, the Reformation rocked European civilization to the core. Vernacular editions of the Bible soon became available in all the languages of Europe. In fact, the proliferation of vernacular Bibles helped break the hegemony of Latin as the language of theology and intellectual discourse — a language that only a tiny and well-educated percentage of the European population could read. Gutenberg and his moveable type printing press. Literacy soared. As presses proliferated and the cost of publishing tracts, treatises, commentaries and books declined, an explosion of printed discourse transformed Europe from a hierarchical culture where subordination and deference prevailed and ancient authority was determinative, to a more fluid culture in which previously unheard-of thoughts and ideas could attempt to take their place in what, by the Enlightenment, was called a “free marketplace of ideas.” Just think of the importance in the American Revolution of the Declaration of Independence, first printed on July 4, 1776, the same day it was adopted by the Second Continental Congress, or Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, America’s first bestseller (Jan. 10, 1776), or the Federalist Papers (1787-88), which “sold” the new Constitution to a skeptical American public. In 1823, just three years before his death, Thomas Jefferson explained to his old friend John Adams that the proliferation of inexpensive printing would help liberate oppressed peoples all over the world. If books can be smuggled into nations living under despotic rule, and people can see their natural rights articulated by individuals like John Locke or Voltaire, they will never rest until they have secured the blessings of liberty. Jefferson wrote, “The light which has been shed on mankind by the art of printing has eminently changed the condition of the world . . . And, while printing is preserved, it can no more recede than the sun return on his course.” If a book clandestinely carried into Persia or Russia or Turkey in 1804 could have a liberating impact, imagine the breathtaking capacity of electronic discourse (or Radio Free Europe for that matter) can have in an era of nearly infinitely more sophisticated communication. That was then. The printing press changed everything. The Digital Revolution Now we are in the early adolescent phase of a more profound revolution, and it too is rocking the world. It’s hard for us to measure the disruption (though we can intuit it) and the revolutionary potency of digital communication. But it is clear that the Internet and social media are essential elements in the bewildering cultural and political wars of our time. Marshall McLuhan was right: In many respects, the medium is the message. If you wanted to voice your political views or your discontentment with the state of things before 1995, you could write a letter to your local newspaper that would be scrutinized by a copy editor for civility, grammar, and diction, and whittled down to manageable size before ever appearing in print. If you wrote something incendiary or abusive, the editor would either throw your letter in the trash or call you on the telephone — back then you had to provide actual name, address and phone number to get a letter considered — and talk you down off the ledge of your strongest pronouncements. Or you had to get yourself to a mimeograph machine. The inexpensive ones were cranked by hand. The best versions had an electric motor. You had to use a typewriter (not a keyboard) to pound out your screed on a persnickety form — on which correction was very difficult, usually by way of blotting — and then attach one part of the form to the drum of the mimeograph machine, make sure the well had plenty of copy fluid (a somewhat addicting smell) and paper, and then crank out five, ten, fifty or five hundred copies of your op ed piece. And that’s when the hard work began, because the only way to get the document into the hands of the public was to mail copies (fold, insert in envelope, add address and stamp, and drop in a post box), hand them out at Hyde Park Corner, or leave them at the back of the room of some public event. If you wanted to include an illustration, well, that was next to impossible given mimeograph technology. The resulting document looked like something cooked up in someone’s basement. The mimeograph machine. “Platform” as Both Noun and Verb Publishing your views to the world was, in short, tedious and time consuming, and if you wanted your opinions to reach the world through a “platform,” there was a gatekeeper to see to it that you played by basic rules of civility. Today, if you want to voice your political views or your discontentment with the state of things, you sit down at your computer, choose your platform (Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, Tik-Tok, your blog) and key in your perspective, whether it is brief (“Lock Her Up!”) or a 75-page manifesto. Thanks to the amazing revolution in design options and user-friendly software, you can now perform all sorts of nifty formatting tricks, add cartoons, photographs, even video packages, and make your dissertation on fluoridating water or the need for universal health care look better (slicker, cleaner, clearer, seemingly “professional,” with more bells and whistles) than the most handsomely printed book of 1743, the year Thomas Jefferson was born in the outback of Virginia. No censorious editor stands between you and your pronouncements. Nobody edits for length. The only grammar and usage cop now is your autocorrect and color-coded grammar warning system on the word processor. Nobody urges you to tone it down (unless you are married) or cut out the name calling. After spending a fraction of the time it would have taken to prepare the old mimeograph version of your dissertation on the evils of hog confinement barns, you can create a professional-looking “publication,” better illustrated than any magazine of the 20th century, and all you have to do is push “send” or “post.” Care to illustrate your thesis? Google Images will serve you up tens of millions of photographs, cartoons, graphs or maps for the price of a couple of keystrokes. Do you want to include a half-remembered quotation from Abraham Lincoln or Leon Trotsky? Five or ten minutes on Google (or another search engine) will not only refine your search, but allow you to cut and paste the quotation without bothering to retype it. The Digital Democracy of Publishing We live in the first time in human history when everyone who has access to a laptop and the Internet can publish. No wonder it’s a little anarchic. The digital revolution has given everyone a printing press, a darkroom and a distribution network, at essentially no cost. The result is Whitmanesque. Discourse is not merely produced by the kind of people who gravitate to newspaper offices and the ivory tower, but by the people who frequent NASCAR, professional sports stadiums, the local tavern, Rotary Clubs, professional wrestling arenas, church suppers, farm implement shows, cowboy poetry gatherings, offbeat political organizations, chamber of commerce dinners, fight clubs, flea markets, book clubs and motorcycle rallies. All of these Americans have something to say and what they have to say would not always pass muster with their high school English teacher. Let freedom ring! But it also jangles. Peer review was a kind of mixed blessing. At its best, it served as a filter that weeded out demonstrably false propositions, bad science, libelous pronouncements and various forms of extremism. Peer review still matters, at least in academic circles, especially science, and in the major journals, including online journals. But it also gave a relatively small number of individuals, often self-important individuals, the power to decide what gets shared with a wider world and what never sees the light of day. The established cultural gatekeepers not only were often blind to important ideas they had no lens to recognize, but they often protected bigotry, injustice, racism and patriarchy against the winds of change. The digital revolution represents a radical democratization of human discourse and expression. It’s heady and intoxicating. Now everyone can publish. Not everyone has something useful to say, but of course that doesn’t prevent them from entering the arena on their own terms. Time After Time of Great Disruption Traditional political discourse has been disrupted and, in some ways, destabilized by the capacity not just of political factions but every individual to weigh in on public policy instantaneously. Howard Dean’s Internet strategy cleared the way for Barack Obama to use social media to prevail in the 2008 presidential election at a time when the establishment of both parties was still wedded to what turned out to be shopworn communication vehicles. Donald Trump rode his Twitter account into the White House, disrupting a Republican establishment that seemed otherwise ready to nominate Jeb Bush in 2016. Twitter’s controversial decision to de-platform – that is, to ban Mr. Trump permanently from its platform (Jan. 8, 2021) has temporarily rendered the former president silent — for the first time in at least five hectic years. Whatever else is true, Twitter’s decision will be economically costly because Trump drove traffic to Twitter in unprecedented and indeed unpredictable ways. It seems inevitable that he will be back on some other platform. The digital revolution might potentially help create what the Enlightenment’s “free marketplace of ideas,” or a meritocracy in which cultural products, including expressions of political opinion, can attract their market share without the various filters that have constrained freedom of expression (except on soap boxes) for most of the history of western civilization. The “silent majority” and the “forgotten Americans” now have a potent megaphone, and they know how to use it. As with most breathtaking new technologies, the early history and adolescence of the digital revolution enable a fairly large level of chaos. Who knew that one of the prime beneficiaries of the Internet would be digital pornography? How did Facebook become the heartland of cat memes? It is truly a brave new world. But it comes at a cost. It turns out people have a lot to get off their chests! Which is to put it lightly. Give the millions of people who were effectively without a public voice for most of their lives — for most of civilization — the opportunity to get into the discourse arena, and at so convenient, inexpensive and unpunishable a manner, and they are going to do some catching up and say things to the wider world that perhaps they were only able to express at the Saturday coffee klatch previously. And if they really want to let it rip, they can create an anonymous or unidentifiable online persona, a kind of no-holds-barred platform to say all the dark or crazy or unpopular things they have been thinking all these years. In fact, the exhilaration of such access to “publishing” is so great that it sometimes prompts otherwise reasonable people to break social, political, religious and cultural taboos just for the secret pleasure of transgression. Just to stir the pot. Just to see their words in print. Adolescence Is Painful: Is Our Democracy Too Old for This? So far, it appears that the American people have not yet developed the critical thinking skills to sort truth from nonsense online, plausible argument from baseless conspiracy theory, science from wishful thinking. Because advanced design programs that are now built into all social media platforms produce discourse that is so polished, beautifully formatted, colorful, engaging and entertaining, it is not possible on the surface to tell the difference between a carefully reasoned argument and what Theodore Roosevelt called “the lunatic fringe.” At a glance, the “look” of an essay about the philosophy of Bertrand Russell is identical to the look of a claim that the Parkland and Sandy Hook school shootings were “false flag” operations perpetrated by the anti-Second Amendment conspirators. On the surface, an article commemorating the Holocaust looks no different in polish and formatting from one denying that the Holocaust even happened. Spellcheck, wraparound text formatting, colorful borders and boxed illustrations give whatever is published the look of serious professionalism, whether the author spent years researching the subject or knocked it out after hearing something annoying on the morning talk shows. The medium is the message, and the message (at least superficially) is that all discourse is born equal. We are going to have to be patient, endure a great deal of noise, and cultural and political catharsis, before the sons and daughters of the digital revolution begin to address the world in less chaotic and less extreme ways. A good Jeffersonian will argue that the cultural “establishment” should not despair over this phenomenon or predict the apocalypse, but simply allow the “yeasty stuff of democracy” to have its day, so that when everyone has had the chance to vent in an unencumbered way, the currently wild and crazy discourse will yield to a saner and more reasonable market of ideas in which, for example, actual evidence, might matter. We can at least hope for the advent of greater civility and maturity in our political discourse. My sense is that these growing pains will diminish over time. The early anarchic phase of unfiltered publishing will give way to a more refined and chastened discourse. The sooner the better if you love American democracy. You can hear more of Clay Jenkinson's views on American history and the humanities on his long-running nationally syndicated public radio program and podcast, The Thomas Jefferson Hour, and the new Governing podcast, The Future In Context.

Via Charles Tiayon

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Edumorfosis.Work

February 19, 2021 3:04 PM

|

The evidence for the harm the pandemic has caused is all around us, but if there is one characteristic that defines humankind it’s our ability to adapt and learn from adversity: over the last year we have carried out the largest experiment in remote working in history. What we now need to do is build on that achievement, instead of just waiting for the pandemic to subside before we go back to working like we did before.

Via Edumorfosis

|

Scooped by

Dennis Swender

February 11, 2021 2:29 PM

|

Unlocking knowledge, empowering minds. Free course notes, videos, instructor insights and more from MIT.

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Anat Lechner's My 2 Cents

January 13, 2021 12:47 PM

|

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Anat Lechner's My 2 Cents

January 13, 2021 12:41 PM

|

To gain business agility, leaders must deconstruct jobs into tasks and deploy workers based on their skills.

Via Anat Lechner PhD

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from IELTS, ESP, EAP and CALL

December 29, 2020 6:09 AM

|

As Robin Wall Kimmerer harvests serviceberries alongside the birds, she considers the ethic of reciprocity that lies at the heart of the gift economy.

Via Dot MacKenzie

At the core of every culture, within their respective holidays and customs lie an almost inherent tradition of gift-exchange. From striped-ribbon boxes that sleep under a tree, to envelopes that don a rich red hue, the idea of “gifts” has manifested itself across nearly every nation and culture, simultaneously embedding itself at the heart of Read More

Via Charles Tiayon

|

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Edumorfosis.Work

April 24, 2021 11:24 AM

|

Founders and executives around the globe have taken lessons learned over the past year to inform their view of what their workplace will look like in the future. At this week's Collision conference, the future of the workplace was top-of-mind--though founders had a wide diversity of expectations about how their companies will work coming out of the pandemic. Here are a few of the most fascinating.

Via Edumorfosis

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Online Marketing Tools

April 11, 2021 12:49 PM

|

Knowledge process outsourcing (KPO) is the outsourcing of core, information-related business activities. KPO involves contracting out work to individuals that typically have advanced degrees and ex…

Via Online Marketing

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Education 2.0 & 3.0

April 11, 2021 12:38 PM

|

Numbers are up across the board for employer-based credential programs as companies develop a robust parallel higher education infrastructure. Research out of credentialing platform Credly found that the number of organizations building their own curriculum and issuing credentials is up 83% since the start of COVID in 2020.

Via Edumorfosis, Yashy Tohsaku

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Edumorfosis.Work

April 11, 2021 12:35 PM

|

The rapid advancement of technology, combined with increased uncertainty, is making the most important career logic of the past counterproductive going forward. The world, to put it bluntly, has changed, but our philosophy around skills development has not. Today's dynamic complexity demands an ability to thrive in ambiguous and poorly defined situations, a context that generates anxiety for most, because it has always felt safer to generalize. Just think about some of the buzzwords that characterized the business advice over the past 40 to 50 years: Core competence, unique skills, deep expertise. For as far back as many of us can remember, the key to success was developing a specialization that allowed us to climb the professional ladder.

Via Edumorfosis

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Edumorfosis.Work

March 25, 2021 3:16 PM

|

By now, it’s clear that the office isn’t going away. And yet, with the rise in remote work and an increasing number of companies adopting hybrid work models, it is just as clear that the role of the office has evolved and the workplace is not likely to ever operate the same as it did prior to the coronavirus pandemic.

While there are still many people that are questioning not only when, but also why should employers bring back employees to the office, the truth is that most workers don’t want to work from home all day, every day. Gensler’s 2020 Workplace Survey found that only 12% of workers want to work from home all the time, while the rest still chose the office as their preferred place to work.

Via Edumorfosis

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Edumorfosis.Work

February 21, 2021 3:47 PM

|

We’re in the midst of the 4th Industrial Revolution—exponential changes in the way we work, live, and interact with one another as a result of the combination of technologies such as machine learning and artificial intelligence intermingling with the physical world to create cyber-physical systems. It could be argued that the 4th Industrial Revolution, also known as Industry 4.0, was already evolving at an exponential rate, but as the world responded to the COVID-19 pandemic, the revolution accelerated. While many are anxious to “return to normal” post-pandemic, the reality is that we are creating a new normal. Let’s take a look at the changes the 4th Industrial Revolution is responsible for and how businesses must re-think their business models and also consider the skills individuals must focus on building to succeed in the new reality.

Via Edumorfosis

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Soup for thought

February 19, 2021 3:07 PM

|

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Talks

February 13, 2021 1:48 PM

|

Last April, states began to sporadically reopen after weeks of being shut down. Georgia was among the first to begin the process, while some states didn’t start lifting restrictions until June.

The uncoordinated reopening caused chaos, according to Sinan Aral, director of MIT’s Initiative on the Digital Economy. Why? Because Georgia pulled in hundreds of thousands of visitors from neighboring states - folks hoping to get a haircut or go bowling.

Aral was tracking Americans on social media, and it became clear to him that having uncoordinated coronavirus policies doesn’t make sense. As people watched their social feeds fill with images of people heading back outside, they stepped out too — even if their state wasn’t at the same phase.

Via Complexity Digest

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Criminology and Economic Theory

February 10, 2021 6:51 AM

|

It takes more than a decent constitution to build a democracy, as anyone who has tried to steer a country out of anarchy or tyranny can attest. And it takes more than well-turned commercial laws to make a healthy market economy. For either to happen, certain values must be widely accepted—yet defining them can be tricky.

Listen to this story

Enjoy more audio and podcasts on iOS or Android.

Joseph Henrich, a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard, has devised a teasing term to describe societies where rules and values have come together with benign results: Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic. The acronym, weird, neatly makes his point that these attributes, and the mindset that goes with them, are the exception not the rule in human history.

The values that underpin weirdness, he writes, include a tough-minded belief in the rule of the law, even at the risk of personal disadvantage; an openness to experimentation in matters of scientific knowledge or social arrangements; and a willingness to trust strangers, from politicians offering new policies to potential business partners. These may not seem original insights, but Mr Henrich’s work is distinguished by the weight he places on the extended family as an obstacle to healthy individualism, and on religious norms as the determinant of family obligations. He reinforces this theme with a welter of polling data and sweeping historical arguments, mostly about medieval Europe.

Via Rob Duke

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from Anat Lechner's My 2 Cents

January 13, 2021 12:44 PM

|

at its first ever fully digital AR/VR-focused conference, facebook introduced 'infinite office' – a platform that offers a virtual working environment.

Via Anat Lechner PhD

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from :: The 4th Era ::

January 11, 2021 4:58 PM

|

For the purposes of this site, the history of human interaction with information may be divided into 4 eras. The first (spoken) era ended with the invention of writing around 3000-4000 BC. The second era ended with the invention of the printing press in 1440. The third era ended, and the fourth began, with the invention of the Internet (depending how one defines its operational beginning) somewhere between 1969 and 1982. We now exist early, but decidedly, in the fourth era. All readers may not agree with this interpretation of the history of information, especially with the division and numbering of the eras. That is not the main point. Rather, it is that humankind presently exists in an era distinctly different from the one that preceded it -- that in fact, this new era is accompanied with, and characterized by, a new - and quite different - information landscape. This new Internet information landscape will challenge, disrupt, and overpower the print-oriented one that came before it. It will not completely obliterate that which preceded it, but it will render it to a subsidiary, rather than primary, level of influence. Just as the printing press altered humanity's relationship with information, thereby resulting in massive restructuring of political, religious, economic, social, educational, cultural, scientific, and other realms of life; so too will the advance of digital technology occasion analogous transformations in the corresponding universe of present and future human activity. This site will concern itself primarily with how K-20 education in the US, and the people who comprise its constituencies, may be affected by this transformative movement from one era to the next. All ideas considered here appear, to me at least, to impact the learning enterprise in some way. Accordingly, this work looks at the present and the future through a lens that is predominantly, but far from entirely, a digital one. -JL

Via Jim Lerman

|

Rescooped by

Dennis Swender

from digital divide information

December 14, 2020 7:54 AM

|

The world no longer rewards us just for what we know — Google knows everything — but for what we can do with what we know.

Via Bonnie Bracey Sutton

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...