Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Charles Tiayon

October 21, 2021 8:29 AM

|

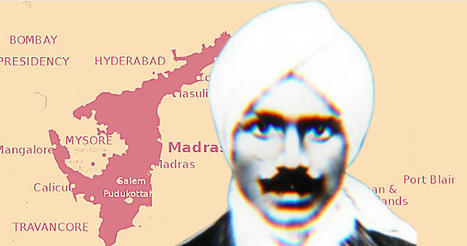

'The Coming Age' offers readers insight into the Tamil writer's nuanced discourse, his strike at the heart of social ills and his unique linguistic capabilities. Subramania Bharati. In the background is a map of the Madras Presidency. Photos: Public domain. Illustration: The Wire Mahakavi Subramania Bharati’s English writings, which includes his journalistic pieces, letters and translations, edited by Meera T. Sundara Rajan, the poet’s great-granddaughter and brought out by Penguin, is a sincere attempt to place him within the literary atlas of ‘Indian’ literature. The publication of Bharati’s English writings assumes significance today when our literary and academic spheres move more towards Indian regional literature translated in English. Although these English writings have already appeared, the present volume demands our attention as it comes from Bharati’s lineage. ‘The Coming Age: Collected English Writings,’ C. Subramania Bharati, New Delhi: Penguin Modern Classics, 2021. Each of these attempts offers a new perspective on Bharati’s English writings. Additionally, the descriptive notes on each piece and those on culture-specific terms may help non-native readers within and outside India to grasp the depth and force of Bharati’s poetics and politics. The contents of the book have been divided into writings pertaining to ‘The National Movement’ and his reflections on linguistic, philosophical and social issues. While celebrating the leaders of the National Movement like Gokhale and Tilak, he was also conscious of securing a place for the struggles of leaders in the Madras Presidency. The final section includes his English translations of Tamil Bhakti poetry as well as translations of his own poems. The English writings display the relation between the uniqueness of his prose style and his immediate (colonial or native) environment on the one hand, and the relation between his English writings and Tamil oeuvre on the other. Poetics of prose The subtitle ‘Collected English Writings’ invites the reader to the relatively unfamiliar side of the Tamil poet. Any reader would notice his forceful diction, syntax, admire his perspicacity and wonder at the ease with which he has used the coloniser’s language to criticise their administration. In his letter to Ramsay Macdonald of the British Labour Party, about the police surveillance on him in French-occupied Pondicherry in connection with the killing of the then Tirunelveli collector, Ashe, by Vanchinathan, he writes: ”The lower police – to whom, by the way, political motives and political crimes were, still are, as strange and unfamiliar as differential calculus – at once imagined that the newspapermen who had been talking swadeshi on the sands of the Madras Beach three years before must be at the bottom of the whole thing…” (55). Also read: Subramania Bharati: One Hundred Years of Revolution Hinting at the administrative coalition between the two rival powers (British and French), he closes the letter, saying: “I wish I had sufficient power of language to depict the whole absurdity and injustice of the thing… But I am beginning to fear that His Excellency’s hands are stayed in this matter by the reactionary elements in his new environment” (61). These English pieces cannot be seen in isolation as they carry traces of mockery and sarcasm that is typical of his Tamil writings. The inherent comic possibilities of prose have been explored to a great extent in these English writings. However, it has been achieved partly by its inter-textual connections with his Tamil writings. A postage stamp issued by the Indian government to honour Bharati. In his reflection on World War I, he says: “The affairs of cawing crows and of ‘civilised nations’, of cats and of ‘supermen’, are all determined by divine laws…” The tone is too close to his allegorical tale, ‘Kaakkai Parliament’ (‘crow parliament’) in which he ridicules the colonial mechanism. Any Tamil reader would recognise the tone and rhythm of the piece, ‘New Birth’ as an English rendering of his canonical Tamil song “Aaduvome pallu paduvome.” While reading ‘The Fox with the Golden Tail: A Fable with an Esoteric Significance,’ the contemporary reader is likely to wonder whether George Orwell modelled his novel, Animal Farm, based on this tale. But, unlike Orwell, who makes his critique of communism explicit, this tale is subtly narrated as to move beyond the particular colonial context, inviting responses from other cultural contexts. This constitutes, we can say, the poetics of our Mahakavi’s prose. Such rewarding pieces also offer the possibilities of reading them within contemporary debates on language, culture and the discourses of modernity. Also read: Was Hindi Really Created by India’s British Colonial Rulers? They spring from his deep sense of awareness of Tamil literature, grammar and tradition without being confined to his admiration for European Romantics as well as Indian nationalists like Tagore. Philosophical aesthetics Bharati’s reflections on religion and spirituality also carry his deep sense of Tamil language and aesthetic concerns. Saying that “mystic books are of value where they deal with ordinary things and cease to be mystic,” he lays his criticism against Brahminical claims. It is this ‘ordinariness’ or the ability to relate with common humans that Bharati regards as the chief feature that distinguishes a Siddha from Nietzsche’s highly rationalised “supermen.” This social consciousness helps him place the woman question as part of the national question. He says: “The situation is nauseating. We are men, that is to say, thinking beings. Our chief work in this world is the understanding and glorification of God’s ways, and not the enslaving of God’s creatures. If any man or nation forgets this, that man or nation is doomed to perdition” (75). This is why his political vision remains inseparable from a social concern, which, he says, needs to be inculcated: “We must spread the contagion of greatness among the people” (42). It is this nuanced discourse, which does not naively talk of women, that demands our attention today. This discourse is closely connected to his views on Europe overcoming a strict anti-colonialism: “We have a special love for Europe, in spite of her blunders and faults” (19). This was extended as a general critique of Western discourses on the ‘Other’ and its root in the Enlightenment. Hence, he says, “Reasoning is not the endless quibbling and hair-splitting of the professional logicians and critics. These are abusers of Reason”(167). This critique of the European Enlightenment arises out of his deep awareness of the “occult element in Tamil speech” which he tried to capture in his exploration of the genre of Tamil ‘prose poems’. But this does not remain purely Tamil as he continuously contemplates on the concepts of Sanskrit tradition and says: “All truth is inspired” (86). He reformulates the same in the Romantic idiom as: “Truer words were never written…Imagination makes a nation’s seers, its poets, and its builders of all types” (104). This critical perception of religion and spirituality led to his contempt for the ‘godmen,’ irrespective of religion: “Three-fourths of the spiritualities trumpeted among men have been proved to be ways of earning money, practiced by clever scoundrels or self-deluded charlatans”(166). For him, ‘spiritual’ is something that pervades all walks of life: “True, patriotism must be spiritual, but that does not mean that differences of belief concerning the nature of the other world should be brought into the theater of secular nation-building”(47). The fact that he said it more than two decades before the partition of India makes him a political messiah, anticipating Frantz Fanon’s warnings of the pitfalls of national consciousness. Such an interest in the sociology of nation-building is articulated in clear terms when he says: “When men bring into political life the bitterness of religious sectarianism, or the spirit which ordained the untouchable and unapproachable castes–well, they commit political suicide; that is all” (44). Bharati could give this warning to the Indian National Congress thanks to his exposure to the anti-caste tradition in Tamil culture and the anti-Brahmin movement of early 20th century Tamil Nadu. This critique of caste, if read in the light of Tamil scholars’ questioning of his affiliation with Brahmin associations, may be fruitful in the context of Dalit studies. While claiming that the practice of caste is “leagues away from the Gita theory,” he says: “Brahmanas have long ceased to think seriously of eternal verities or the sciences of this earth” (78). This is how he differs from Gandhi and other leaders of his time who choose to condemn untouchability without critiquing the caste system. Also read: ‘Never a Mahatma’: A Look at Ambedkar’s Gandhi If his reflections on colonialism and nationalism suggest a possibility of evolving a poetics of prose, his translations and his continuous fascination with the form of fables draw attention to philosophical aesthetics. Reading this volume would definitely help present day readers ponder over theoretical and aesthetic issues thanks to Bharati’s balancing act between form and content. Claims to legacy The editor of this collection identifies Vijaya Bharati, Bharati’s grand-daughter and her own mother, as the first scholar who worked on his works. She claims that Vijaya Bharati “learned the poet’s verses as Bharati, in keeping with the Indian tradition that unites poetry and music, originally sang them to his family… One of her cherished goals was to publish Bharati’s original English writings in a new edition” (xii). Subramanya Bharati and his wife, Chellamma. Photo: Public domain/Wikipedia The editor of this volume has no one to acknowledge except the publishing desk. There is an ethical flaw in this. In addition to the efforts of Bharati’s wife Chellamma and his brother Viswanatha Iyer to get his works published, there was a scholarly tradition which unearthed and published the sources. It includes writer Va. Ra, poet Pe. Thooran, scholars like Ra. A. Paananaban, A.K. Chettiyar, Ilasai Maniyan, C.S. Subramaniyan, V.G. Seenivasan, The. Mu. C. Ragunathan and Pe. Su. Maniyan. The history of each one’s efforts has been so well-documented that any interested reader can get a clear picture of Tamil scholarship on Bharati in early and mid-20th century Tamil Nadu. Consolidating these efforts, Seeni. Viswanathan brought out a classic edition in 2012, authenticating the periodisation of Bharathiyar’s works, including his English writings and translations. Earlier, the All India Subramania Bharati Centenary Celebrations Committee also brought out a good collection of Bharati’s works, adding to his English works a scholarly introduction by K. Swaminathan in 1984. In our own time, we have scholars like Venkatachalapathy, Manigandan and a few others whose work on Bharathiyar have received honours from the government of Tamil Nadu. Anyone who is acquainted with Bharati scholarship would feel hurt at this total neglect, in the book, of the scholarly tradition that has toiled to preserve and publish Bharati’s works over time. Translation ethics Readers who compare Bharati’s translations (of Tamil Bhakti poems and his own), with the translations of Bharati by others, would definitely find in Bharati an able translator with an enormous confidence in the source and target languages, though Bharati was a little apprehensive about his English translations. A sample translation from Nammalwar’s Tiruvaymoli may stand as a proof of this: O dear soul of Mine,

O great Life that made and pierced and ate and spouted and measured

All this immense space,

O Glorious Life that made the oceans, dwelt therein and churned

And stopped and broke them,

Thou who art unto the Gods what the gods are unto men,

O Soul unique of all the worlds, whither shall I go to meet Thee? (139) In addition, the inclusion of his translations in this collection will push the readers to see the mutual illumination of his English and Tamil writings. It is here that Bharati remains a frontrunner of the tradition of bilingual writers like Ayyappa Panicker, U.R. Ananthamurthy, Girish Karnad, and Dilip Chitre who have continued to inspire us in mother-tongue scholarship. Acknowledging this scholarly tradition and reading Bharati’s English writings in relation to his Tamil work may help the readers understand and appreciate why we call him ‘Mahakavi’. R. Azhagarasan is professor of English, University of Madras.

Researchers across Africa, Asia and the Middle East are building their own language models designed for local tongues, cultural nuance and digital independence

"In a high-stakes artificial intelligence race between the United States and China, an equally transformative movement is taking shape elsewhere. From Cape Town to Bangalore, from Cairo to Riyadh, researchers, engineers and public institutions are building homegrown AI systems, models that speak not just in local languages, but with regional insight and cultural depth.

The dominant narrative in AI, particularly since the early 2020s, has focused on a handful of US-based companies like OpenAI with GPT, Google with Gemini, Meta’s LLaMa, Anthropic’s Claude. They vie to build ever larger and more capable models. Earlier in 2025, China’s DeepSeek, a Hangzhou-based startup, added a new twist by releasing large language models (LLMs) that rival their American counterparts, with a smaller computational demand. But increasingly, researchers across the Global South are challenging the notion that technological leadership in AI is the exclusive domain of these two superpowers.

Instead, scientists and institutions in countries like India, South Africa, Egypt and Saudi Arabia are rethinking the very premise of generative AI. Their focus is not on scaling up, but on scaling right, building models that work for local users, in their languages, and within their social and economic realities.

“How do we make sure that the entire planet benefits from AI?” asks Benjamin Rosman, a professor at the University of the Witwatersrand and a lead developer of InkubaLM, a generative model trained on five African languages. “I want more and more voices to be in the conversation”.

Beyond English, beyond Silicon Valley

Large language models work by training on massive troves of online text. While the latest versions of GPT, Gemini or LLaMa boast multilingual capabilities, the overwhelming presence of English-language material and Western cultural contexts in these datasets skews their outputs. For speakers of Hindi, Arabic, Swahili, Xhosa and countless other languages, that means AI systems may not only stumble over grammar and syntax, they can also miss the point entirely.

“In Indian languages, large models trained on English data just don’t perform well,” says Janki Nawale, a linguist at AI4Bharat, a lab at the Indian Institute of Technology Madras. “There are cultural nuances, dialectal variations, and even non-standard scripts that make translation and understanding difficult.” Nawale’s team builds supervised datasets and evaluation benchmarks for what specialists call “low resource” languages, those that lack robust digital corpora for machine learning.

It’s not just a question of grammar or vocabulary. “The meaning often lies in the implication,” says Vukosi Marivate, a professor of computer science at the University of Pretoria, in South Africa. “In isiXhosa, the words are one thing but what’s being implied is what really matters.” Marivate co-leads Masakhane NLP, a pan-African collective of AI researchers that recently developed AFROBENCH, a rigorous benchmark for evaluating how well large language models perform on 64 African languages across 15 tasks. The results, published in a preprint in March, revealed major gaps in performance between English and nearly all African languages, especially with open-source models.

Similar concerns arise in the Arabic-speaking world. “If English dominates the training process, the answers will be filtered through a Western lens rather than an Arab one,” says Mekki Habib, a robotics professor at the American University in Cairo. A 2024 preprint from the Tunisian AI firm Clusterlab finds that many multilingual models fail to capture Arabic’s syntactic complexity or cultural frames of reference, particularly in dialect-rich contexts.

Governments step in

For many countries in the Global South, the stakes are geopolitical as well as linguistic. Dependence on Western or Chinese AI infrastructure could mean diminished sovereignty over information, technology, and even national narratives. In response, governments are pouring resources into creating their own models.

Saudi Arabia’s national AI authority, SDAIA, has built ‘ALLaM,’ an Arabic-first model based on Meta’s LLaMa-2, enriched with more than 540 billion Arabic tokens. The United Arab Emirates has backed several initiatives, including ‘Jais,’ an open-source Arabic-English model built by MBZUAI in collaboration with US chipmaker Cerebras Systems and the Abu Dhabi firm Inception. Another UAE-backed project, Noor, focuses on educational and Islamic applications.

In Qatar, researchers at Hamad Bin Khalifa University, and the Qatar Computing Research Institute, have developed the Fanar platform and its LLMs Fanar Star and Fanar Prime. Trained on a trillion tokens of Arabic, English, and code, Fanar’s tokenization approach is specifically engineered to reflect Arabic’s rich morphology and syntax.

India has emerged as a major hub for AI localization. In 2024, the government launched BharatGen, a public-private initiative funded with 235 crore (€26 million) initiative aimed at building foundation models attuned to India’s vast linguistic and cultural diversity. The project is led by the Indian Institute of Technology in Bombay and also involves its sister organizations in Hyderabad, Mandi, Kanpur, Indore, and Madras. The programme’s first product, e-vikrAI, can generate product descriptions and pricing suggestions from images in various Indic languages. Startups like Ola-backed Krutrim and CoRover’s BharatGPT have jumped in, while Google’s Indian lab unveiled MuRIL, a language model trained exclusively on Indian languages. The Indian governments’ AI Mission has received more than180 proposals from local researchers and startups to build national-scale AI infrastructure and large language models, and the Bengaluru-based company, AI Sarvam, has been selected to build India’s first ‘sovereign’ LLM, expected to be fluent in various Indian languages.

In Africa, much of the energy comes from the ground up. Masakhane NLP and Deep Learning Indaba, a pan-African academic movement, have created a decentralized research culture across the continent. One notable offshoot, Johannesburg-based Lelapa AI, launched InkubaLM in September 2024. It’s a ‘small language model’ (SLM) focused on five African languages with broad reach: Swahili, Hausa, Yoruba, isiZulu and isiXhosa.

“With only 0.4 billion parameters, it performs comparably to much larger models,” says Rosman. The model’s compact size and efficiency are designed to meet Africa’s infrastructure constraints while serving real-world applications. Another African model is UlizaLlama, a 7-billion parameter model developed by the Kenyan foundation Jacaranda Health, to support new and expectant mothers with AI-driven support in Swahili, Hausa, Yoruba, Xhosa, and Zulu.

India’s research scene is similarly vibrant. The AI4Bharat laboratory at IIT Madras has just released IndicTrans2, that supports translation across all 22 scheduled Indian languages. Sarvam AI, another startup, released its first LLM last year to support 10 major Indian languages. And KissanAI, co-founded by Pratik Desai, develops generative AI tools to deliver agricultural advice to farmers in their native languages.

The data dilemma

Yet building LLMs for underrepresented languages poses enormous challenges. Chief among them is data scarcity. “Even Hindi datasets are tiny compared to English,” says Tapas Kumar Mishra, a professor at the National Institute of Technology, Rourkela in eastern India. “So, training models from scratch is unlikely to match English-based models in performance.”

Rosman agrees. “The big-data paradigm doesn’t work for African languages. We simply don’t have the volume.” His team is pioneering alternative approaches like the Esethu Framework, a protocol for ethically collecting speech datasets from native speakers and redistributing revenue back to further development of AI tools for under-resourced languages. The project’s pilot used read speech from isiXhosa speakers, complete with metadata, to build voice-based applications.

In Arab nations, similar work is underway. Clusterlab’s 101 Billion Arabic Words Dataset is the largest of its kind, meticulously extracted and cleaned from the web to support Arabic-first model training.

The cost of staying local

But for all the innovation, practical obstacles remain. “The return on investment is low,” says KissanAI’s Desai. “The market for regional language models is big, but those with purchasing power still work in English.” And while Western tech companies attract the best minds globally, including many Indian and African scientists, researchers at home often face limited funding, patchy computing infrastructure, and unclear legal frameworks around data and privacy.

“There’s still a lack of sustainable funding, a shortage of specialists, and insufficient integration with educational or public systems,” warns Habib, the Cairo-based professor. “All of this has to change.”

A different vision for AI

Despite the hurdles, what’s emerging is a distinct vision for AI in the Global South – one that favours practical impact over prestige, and community ownership over corporate secrecy.

“There’s more emphasis here on solving real problems for real people,” says Nawale of AI4Bharat. Rather than chasing benchmark scores, researchers are aiming for relevance: tools for farmers, students, and small business owners.

And openness matters. “Some companies claim to be open-source, but they only release the model weights, not the data,” Marivate says. “With InkubaLM, we release both. We want others to build on what we’ve done, to do it better.”

In a global contest often measured in teraflops and tokens, these efforts may seem modest. But for the billions who speak the world’s less-resourced languages, they represent a future in which AI doesn’t just speak to them, but with them."

Sibusiso Biyela, Amr Rageh and Shakoor Rather

20 May 2025

https://www.natureasia.com/en/nmiddleeast/article/10.1038/nmiddleeast.2025.65

#metaglossia_mundus

"(Re)traduire les autrices du XIXe s. aujourd’hui : d’Emilia Pardo Bazán à la redécouverte d’un matrimoine européen (La Main De Thôt)

Date de tombée (deadline) : 15 Novembre 2025

À : UT2J

Voir sur Twitter

Publié le 18 Juin 2025 par Marc Escola (Source : Carole Fillière)

La Main De Thôt 2026 - N° 14

(Re)traduire les autrices du XIXe siècle aujourd’hui :

d’Emilia Pardo Bazán à la redécouverte d’un matrimoine européen

Amélie Florenchie, Emilie Guyard et Carole Fillière (éds.)

La circulation des textes dans l’espace public est un enjeu politique majeur. L’invisibilisation systématique des textes d’autorité féminine est un phénomène qui a largement été constaté et qui est désormais réparé grâce à un processus dit de réhabilitation [1]. Il s’agit de récupérer tout un patrimoine féminin -un matrimoine [2]- et de le faire connaître au-delà des frontières quelles qu’elles soient, réelles ou symboliques.

Du cas Emilia…

A l’instar d’autres auteurs espagnols du XIXe siècle, mais plus encore parce que c’était une femme et une personnalité publique polémique, Emilia Pardo Bazán n’a été que peu traduite en français [3] : on compte aujourd’hui seulement deux romans traduits (Los pazos de Ulloa et Un viaje de novios [4]) et une quarantaine de nouvelles traduites, réparties dans cinq recueils [5], alors qu’elle est l’autrice d’une œuvre prolifique : plus de 40 romans, plus de 600 nouvelles, des pièces de théâtre, des recueils de poésie, des centaines d’articles de presse, de nombreuses conférences, une autobiographie, plusieurs essais, biographies, hagiographies, carnets de voyage, livres de cuisine, etc.

Emilia Pardo Bazán est née en 1851 à La Corogne, en plein règne d’Isabelle II, et décédée en 1921 dans son pazo de Meirás, non loin de sa ville natale. Elle est également l’autrice d’une œuvre moderne, car elle fut pionnière dans bien des domaines, comme le naturalisme (La cuestión palpitante) ou du le genre policier (« La gota de sangre », « La cana », etc.). Elle fut enfin une femme moderne, engagée dans la défense des droits des femmes puis ouvertement féministe. Autant d’éléments qui ont contribué, par la suite, à une invisibilisation partielle de son œuvre.

De nombreux travaux ont été menés sur l’œuvre d’Emilia Pardo Bazán, sur sa réception à l’étranger, et notamment en France, mais nous proposons d’aborder cette œuvre à cheval sur le XIXe et le XXe siècles sous l’angle de sa traduction pour la faire (re)découvrir à un public francophone. Le projet NUMILIA [6] s’est ainsi donné pour objectif de « réhabiliter » une partie de l’œuvre de l’autrice avec la publication de la traduction inédite en français de « La gota de sangre » coordonnée par Emilie Guyard chez Un@éditions et la prochaine publication de la traduction d’une sélection de nouvelles féministes inédites en français coordonnées par Amélie Florenchie et Catherine Orsini, chez le même éditeur [7]. Une journée d’études organisée en avril 2025 autour de ces deux publications est à l’origine de ce nouveau numéro de LMDT dont la première partie est consacrée au cas d’Emilia Pardo Bazán et la seconde aux autrices européennes.

… à l’Europe du XIXe (re)traduite de nos jours

Dans ce numéro, il s’agira d’entamer un dialogue avec d’autres chercheur.euses sur ce que signifie (re)traduire au XXIe siècle l’œuvre d’écrivaines européennes du XIXe siècle et réhabiliter un matrimoine encore largement méconnu en tant que tel, depuis une perspective qui ne peut ignorer ni l’évolution de la condition des femmes ni celle du regard qui est porté sur leurs productions culturelles et artistiques. Voici quelques lignes de recherche :

1. Qui sont les autrices du matrimoine européen du XIXe siècle à (re)traduire ?

2. Quels sont les enjeux de la retraduction d'une autrice du canon ?

3. Qu'implique aujourd’hui la traduction d’un texte écrit par une femme du XIXe siècle ? Et la traduction d’un texte écrit par une féministe du XIXe siècle ?

4. Quelles stratégies utiliser pour traduire aujourd'hui un texte qui s’inspire de courants et tendances esthétiques du XIXe siècle (romantisme, réalisme, naturalisme, modernisme, mais aussi genres émergents comme le genre policier, le genre fantastique, etc.) ?

5. Qu’est-ce qu’une traduction féministe ? Quels en sont les objectifs et les éventuelles limites ?

—

BIBLIOGRAPHIE indicative

Emilia Pardo Bazán

Bieder, Maryellen, (1995) « Emilia Pardo Bazán y la emergencia del discurso feminista » in Zavala, Iris M. (coord.), Breve historia feminista de la literatura española (en lengua castellana). V. La literatura escrita por mujer (Del s. XIX a la actualidad). Barcelone, Anthropos, pp. 76-97.

Burdiel, Isabel, (2021 [2019]) Emilia Pardo Bazán. Madrid, Taurus. Col. Españoles eminentes.

Freire López, Ana María, (2005) « Las traducciones de la obra de Emilia Pardo Bazan en vida de la escritora », La Tribuna: cadernos de estudios da Casa Museo Emilia Pardo Bazán. Nº 3, pp. 21-38, disponible sur : https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/las-traducciones-de-la-obra-de-emilia-pardo-bazan-en-vida-de-la-escritora/html/020e2b4a-82b2-11df-acc7-002185ce6064_10.html#I_0

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (1883 [1975]) La tribuna. Édition de Benito Varela Jácome. Madrid, Cátedra.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2008 [1990]) Le château d’Ulloa. Traduction de Nelly Clémessy. Paris, Viviane Hamy.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (1992a) Nouvelles de Galice. Édition bilingue. Préface et traduction d’Isabelle Dupré & Caroline Pascal. Nantes, Le Passeur-Cecofop.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2016) « Feminista, d’Emilia Pardo Bazán ». Traduction de Carole Fillière, in Hibbs, Solange et Ramon, Viviane (coords.), Voix de femmes. Hommage à Karen Meschia. Toulouse, Presses du Mirail, p. 40-43.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2018) El encaje roto. Antología de cuentos de violencia contra las mujeres. Édition et prologue de Cristina Patiño Eirín. Saragosse, Contraseña.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2021 [1999]) La mujer española y otros escritos. Édition de Guadalupe Gómez-Ferrer. Madrid, Cátedra, colección « Clásicos del feminismo ».

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2021a) Algo de feminismo y otros textos combativos. Sélection, édition et notes de Marisa Sotelo Vázquez. Madrid, Alianza editorial.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2021b) Contes d’amour. Traduction d’Isabelle Taillandier. Clamecy, La Reine Blanche.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2022a) La dentelle déchirée. Traduction d’Isabelle Taillandier. Clamecy, La Reine Blanche.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2022b) Naufragées. Traduction d’Isabelle Taillandier. Clamecy, La Reine Blanche.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2025) Une goutte de sang. Traduction collective coordonnée par Emilie Guyard. Bordeaux, Un@éditions. Disponible sur : https://una-editions.fr/une-goutte-de-sang/

Thion Soriano-Mollá, Dolores, (2021) « Emilia Pardo Bazán, una intelectual moderna, también de la Edad de Plata », Feminismo/s. Nº 37, pp. 53-80.

Traduction féministe

Brufau Alvira, Nuria, (2011) “Traducción y género: el estado de la cuestión en España = Translation and gender: the state of the art in Spain” @ MonTI 3, 181-207.

Castro Vázquez, Olga & Emek Ergun, (2017) Feminist Translation Studies. Local and Transnational Perspectives. London, Routledge.

Flotow, Luise von, (1997) Translation and Gender. Translating in the ‘Era of Feminism’. Manchester: St. Jerome.

Flotow, Luise von & Farzaneh Farahzad (eds.), (2017) Translating Women. Different Voices and New Horizons. New York: Routledge.

Flotow, Luise von & Hala Kamal, (2020), The Routledge Handbook of Translation, Feminism and Gender. London: Routledge.

Federici, Eleonora, (2011), Translating Gender. Bern: Peter Lang.

Godayol Nogué, Pilar, (2017) Tres escritoras censuradas. Simone de Beauvoir, Betty Friedan y Mary McCarthy. Granada: Comares. ISBN 9788490454893. [2016. Tres escriptores censurades. Simone de Beauvoir, Betty Friedan & Mary McCarthy. Lleida: Punctum. ISBN 9788494377990]

Godayol Nogué, Pilar, (2019) “Translation and Gender” @ Valdeón, Roberto & África Vidal (eds.) 2019. Routledge Handbook of Spanish Translation Studies, 102-117. London: Routledge.

Godayol Nogué, Pilar, (2019b) “Feminist translation” @ Wyke, Ben Van & Kelly Washbourne (eds.) 2019. Routledge Handbook of Literary Translation Studies, 468-481. London: Routledge.

Hurtado Albir, Amparo, (2001) Traducción y traductología. Madrid, Ediciones Cátedra.

Massardier-Kenney, Françoise, (1997), « Towards e Redifinition of Feminist Translation Practice », The Translator. Nº3 (1), pp. 55-69.

Oster, Corinne, (2013) « La traduction est-elle une femme comme les autres ? – ou à quoi servent les études de genre en traduction ? », La main de Thôt. Nº1, disponible sur : http://interfas.univ-tlse2.fr/lamaindethot/127

Panchón Hidalgo, Marian & Gora Zaragoza Ninet, (2023) « Recuperación (de textos censurados de escritoras) ». Dictionnaire du genre en traduction / Dictionary of Gender in Translation / Diccionario del género en traducción. Disponible sur https://worldgender.cnrs.fr/es/entradas/recuperacion-de-textos-censurados-de-escritoras/

Riley, Catherine, (2018) Feminism and Women’s Writing. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Santaemilia Ruiz, José (ed.), (2017) Traducir para la igualdad sexual / Translating for sexual equality. Granada: Comares.

Sardin, Pascale, (2009) Traduire le genre : femmes en traduction. Paris (France) : Presses Sorbonne nouvelle.

Simon, Sherry, (2023) Le genre en traduction : identité culturelle et politiques de transmission. Traduction de Corinne Oster. Arras, Artois Presses Université.

Matrimoine

Caeymaex, Florence, (2021) « Reprise. Mémoire, histoire et espace public à l’épreuve du matrimoine », Matrimoine. Quand des femmes occupent l’espace public. Cahiers du Centre Pluridisciplinaire de la Transmission de la Mémoire, #2, MNEMA- Cité Miroir, Liège, p. 177-191.

Chabod, France, (2023) « En quête du matrimoine au Centre des archives du féminisme », Bulletin des Bibliothèques de France, 2, p.1-9.

Donadille, Julien, (2019) « Un "matrimoine de raison" Que faire des fonds patrimoniaux non classés dans une bibliothèque territoriale ? », Bulletin des Bibliothèques de France, 21 novembre 2019, p.1-7.

Évain, Aurore, (2008) « Histoire d’‘autrice’, de l’époque latine à nos jours », Femmes et langues, numéro spécial de la revue Sêméion. Travaux de sémiologie, Anne-Marie HOUDEBINE (dir.), 2008, pp. 53-62, réédition numérique, http://siefar.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Histoire-dautrice-A_-Evain.pdf , SIEFAR (Société Internationale pour l'Étude des Femmes de l'Ancien Régime).

Hertz, Ellen, (2002) « Le matrimoine » dans M.-O. GONSETH, J. HAINARD et KAEHR R. (dir.), Le musée cannibale, Neuchâtel, Musée d’ethnographie, p. 153-168.

Moreau, Antoine, (2018) « Matrimoine, le patrimoine à l’ère de l’internet et du numérique ». Hyperheritage International Symposium (HIS) 5, Patrimoines et design d’expérience à l’ère numérique., May, Constantine, Algérie.

Riuz, Geneviève, (2020) « Non, “matrimoine” n’est pas un néologisme », Hémisphères, revue suisse de la recherche et de ses applications, no18.

—

Les propositions (10 lignes maximum, comprenant un titre, un résumé et des mots-clés, en français ou en espagnol) doivent être envoyées au plus tard le 15 novembre 2025 aux adresses suivantes : carole.filliere@univ-tlse2.fr, emilie.guyard@univ-pau.fr et aflorenchie@u-bordeaux-montaigne.fr

Les articles sélectionnés sur proposition seront à envoyer aux mêmes adresses pour le 1er mars 2026.

Responsable :

Amélie Florenchie, Emilie Guyard, Carole Fillière

Url de référence :

https://interfas.univ-tlse2.fr/lamaindethot/

https://www.fabula.org/actualites/128303/la-main-de-thot-2026-n-14-re-traduire-les-autrices.html

#metaglossia_mundus

"(Re)traduire les autrices du XIXe s. aujourd’hui : d’Emilia Pardo Bazán à la redécouverte d’un matrimoine européen (La Main De Thôt)

Date de tombée (deadline) : 15 Novembre 2025

À : UT2J

Publié le 18 Juin 2025 par Marc Escola (Source : Carole Fillière)

La Main De Thôt 2026 - N° 14

(Re)traduire les autrices du XIXe siècle aujourd’hui :

d’Emilia Pardo Bazán à la redécouverte d’un matrimoine européen

Amélie Florenchie, Emilie Guyard et Carole Fillière (éds.)

La circulation des textes dans l’espace public est un enjeu politique majeur. L’invisibilisation systématique des textes d’autorité féminine est un phénomène qui a largement été constaté et qui est désormais réparé grâce à un processus dit de réhabilitation [1]. Il s’agit de récupérer tout un patrimoine féminin -un matrimoine [2]- et de le faire connaître au-delà des frontières quelles qu’elles soient, réelles ou symboliques.

Du cas Emilia…

A l’instar d’autres auteurs espagnols du XIXe siècle, mais plus encore parce que c’était une femme et une personnalité publique polémique, Emilia Pardo Bazán n’a été que peu traduite en français [3] : on compte aujourd’hui seulement deux romans traduits (Los pazos de Ulloa et Un viaje de novios [4]) et une quarantaine de nouvelles traduites, réparties dans cinq recueils [5], alors qu’elle est l’autrice d’une œuvre prolifique : plus de 40 romans, plus de 600 nouvelles, des pièces de théâtre, des recueils de poésie, des centaines d’articles de presse, de nombreuses conférences, une autobiographie, plusieurs essais, biographies, hagiographies, carnets de voyage, livres de cuisine, etc.

Emilia Pardo Bazán est née en 1851 à La Corogne, en plein règne d’Isabelle II, et décédée en 1921 dans son pazo de Meirás, non loin de sa ville natale. Elle est également l’autrice d’une œuvre moderne, car elle fut pionnière dans bien des domaines, comme le naturalisme (La cuestión palpitante) ou du le genre policier (« La gota de sangre », « La cana », etc.). Elle fut enfin une femme moderne, engagée dans la défense des droits des femmes puis ouvertement féministe. Autant d’éléments qui ont contribué, par la suite, à une invisibilisation partielle de son œuvre.

De nombreux travaux ont été menés sur l’œuvre d’Emilia Pardo Bazán, sur sa réception à l’étranger, et notamment en France, mais nous proposons d’aborder cette œuvre à cheval sur le XIXe et le XXe siècles sous l’angle de sa traduction pour la faire (re)découvrir à un public francophone. Le projet NUMILIA [6] s’est ainsi donné pour objectif de « réhabiliter » une partie de l’œuvre de l’autrice avec la publication de la traduction inédite en français de « La gota de sangre » coordonnée par Emilie Guyard chez Un@éditions et la prochaine publication de la traduction d’une sélection de nouvelles féministes inédites en français coordonnées par Amélie Florenchie et Catherine Orsini, chez le même éditeur [7]. Une journée d’études organisée en avril 2025 autour de ces deux publications est à l’origine de ce nouveau numéro de LMDT dont la première partie est consacrée au cas d’Emilia Pardo Bazán et la seconde aux autrices européennes.

… à l’Europe du XIXe (re)traduite de nos jours

Dans ce numéro, il s’agira d’entamer un dialogue avec d’autres chercheur.euses sur ce que signifie (re)traduire au XXIe siècle l’œuvre d’écrivaines européennes du XIXe siècle et réhabiliter un matrimoine encore largement méconnu en tant que tel, depuis une perspective qui ne peut ignorer ni l’évolution de la condition des femmes ni celle du regard qui est porté sur leurs productions culturelles et artistiques. Voici quelques lignes de recherche :

1. Qui sont les autrices du matrimoine européen du XIXe siècle à (re)traduire ?

2. Quels sont les enjeux de la retraduction d'une autrice du canon ?

3. Qu'implique aujourd’hui la traduction d’un texte écrit par une femme du XIXe siècle ? Et la traduction d’un texte écrit par une féministe du XIXe siècle ?

4. Quelles stratégies utiliser pour traduire aujourd'hui un texte qui s’inspire de courants et tendances esthétiques du XIXe siècle (romantisme, réalisme, naturalisme, modernisme, mais aussi genres émergents comme le genre policier, le genre fantastique, etc.) ?

5. Qu’est-ce qu’une traduction féministe ? Quels en sont les objectifs et les éventuelles limites ?

—

BIBLIOGRAPHIE indicative

Emilia Pardo Bazán

Bieder, Maryellen, (1995) « Emilia Pardo Bazán y la emergencia del discurso feminista » in Zavala, Iris M. (coord.), Breve historia feminista de la literatura española (en lengua castellana). V. La literatura escrita por mujer (Del s. XIX a la actualidad). Barcelone, Anthropos, pp. 76-97.

Burdiel, Isabel, (2021 [2019]) Emilia Pardo Bazán. Madrid, Taurus. Col. Españoles eminentes.

Freire López, Ana María, (2005) « Las traducciones de la obra de Emilia Pardo Bazan en vida de la escritora », La Tribuna: cadernos de estudios da Casa Museo Emilia Pardo Bazán. Nº 3, pp. 21-38, disponible sur : https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/las-traducciones-de-la-obra-de-emilia-pardo-bazan-en-vida-de-la-escritora/html/020e2b4a-82b2-11df-acc7-002185ce6064_10.html#I_0

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (1883 [1975]) La tribuna. Édition de Benito Varela Jácome. Madrid, Cátedra.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2008 [1990]) Le château d’Ulloa. Traduction de Nelly Clémessy. Paris, Viviane Hamy.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (1992a) Nouvelles de Galice. Édition bilingue. Préface et traduction d’Isabelle Dupré & Caroline Pascal. Nantes, Le Passeur-Cecofop.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2016) « Feminista, d’Emilia Pardo Bazán ». Traduction de Carole Fillière, in Hibbs, Solange et Ramon, Viviane (coords.), Voix de femmes. Hommage à Karen Meschia. Toulouse, Presses du Mirail, p. 40-43.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2018) El encaje roto. Antología de cuentos de violencia contra las mujeres. Édition et prologue de Cristina Patiño Eirín. Saragosse, Contraseña.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2021 [1999]) La mujer española y otros escritos. Édition de Guadalupe Gómez-Ferrer. Madrid, Cátedra, colección « Clásicos del feminismo ».

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2021a) Algo de feminismo y otros textos combativos. Sélection, édition et notes de Marisa Sotelo Vázquez. Madrid, Alianza editorial.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2021b) Contes d’amour. Traduction d’Isabelle Taillandier. Clamecy, La Reine Blanche.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2022a) La dentelle déchirée. Traduction d’Isabelle Taillandier. Clamecy, La Reine Blanche.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2022b) Naufragées. Traduction d’Isabelle Taillandier. Clamecy, La Reine Blanche.

Pardo Bazán, Emilia, (2025) Une goutte de sang. Traduction collective coordonnée par Emilie Guyard. Bordeaux, Un@éditions. Disponible sur : https://una-editions.fr/une-goutte-de-sang/

Thion Soriano-Mollá, Dolores, (2021) « Emilia Pardo Bazán, una intelectual moderna, también de la Edad de Plata », Feminismo/s. Nº 37, pp. 53-80.

Traduction féministe

Brufau Alvira, Nuria, (2011) “Traducción y género: el estado de la cuestión en España = Translation and gender: the state of the art in Spain” @ MonTI 3, 181-207.

Castro Vázquez, Olga & Emek Ergun, (2017) Feminist Translation Studies. Local and Transnational Perspectives. London, Routledge.

Flotow, Luise von, (1997) Translation and Gender. Translating in the ‘Era of Feminism’. Manchester: St. Jerome.

Flotow, Luise von & Farzaneh Farahzad (eds.), (2017) Translating Women. Different Voices and New Horizons. New York: Routledge.

Flotow, Luise von & Hala Kamal, (2020), The Routledge Handbook of Translation, Feminism and Gender. London: Routledge.

Federici, Eleonora, (2011), Translating Gender. Bern: Peter Lang.

Godayol Nogué, Pilar, (2017) Tres escritoras censuradas. Simone de Beauvoir, Betty Friedan y Mary McCarthy. Granada: Comares. ISBN 9788490454893. [2016. Tres escriptores censurades. Simone de Beauvoir, Betty Friedan & Mary McCarthy. Lleida: Punctum. ISBN 9788494377990]

Godayol Nogué, Pilar, (2019) “Translation and Gender” @ Valdeón, Roberto & África Vidal (eds.) 2019. Routledge Handbook of Spanish Translation Studies, 102-117. London: Routledge.

Godayol Nogué, Pilar, (2019b) “Feminist translation” @ Wyke, Ben Van & Kelly Washbourne (eds.) 2019. Routledge Handbook of Literary Translation Studies, 468-481. London: Routledge.

Hurtado Albir, Amparo, (2001) Traducción y traductología. Madrid, Ediciones Cátedra.

Massardier-Kenney, Françoise, (1997), « Towards e Redifinition of Feminist Translation Practice », The Translator. Nº3 (1), pp. 55-69.

Oster, Corinne, (2013) « La traduction est-elle une femme comme les autres ? – ou à quoi servent les études de genre en traduction ? », La main de Thôt. Nº1, disponible sur : http://interfas.univ-tlse2.fr/lamaindethot/127

Panchón Hidalgo, Marian & Gora Zaragoza Ninet, (2023) « Recuperación (de textos censurados de escritoras) ». Dictionnaire du genre en traduction / Dictionary of Gender in Translation / Diccionario del género en traducción. Disponible sur https://worldgender.cnrs.fr/es/entradas/recuperacion-de-textos-censurados-de-escritoras/

Riley, Catherine, (2018) Feminism and Women’s Writing. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Santaemilia Ruiz, José (ed.), (2017) Traducir para la igualdad sexual / Translating for sexual equality. Granada: Comares.

Sardin, Pascale, (2009) Traduire le genre : femmes en traduction. Paris (France) : Presses Sorbonne nouvelle.

Simon, Sherry, (2023) Le genre en traduction : identité culturelle et politiques de transmission. Traduction de Corinne Oster. Arras, Artois Presses Université.

Matrimoine

Caeymaex, Florence, (2021) « Reprise. Mémoire, histoire et espace public à l’épreuve du matrimoine », Matrimoine. Quand des femmes occupent l’espace public. Cahiers du Centre Pluridisciplinaire de la Transmission de la Mémoire, #2, MNEMA- Cité Miroir, Liège, p. 177-191.

Chabod, France, (2023) « En quête du matrimoine au Centre des archives du féminisme », Bulletin des Bibliothèques de France, 2, p.1-9.

Donadille, Julien, (2019) « Un "matrimoine de raison" Que faire des fonds patrimoniaux non classés dans une bibliothèque territoriale ? », Bulletin des Bibliothèques de France, 21 novembre 2019, p.1-7.

Évain, Aurore, (2008) « Histoire d’‘autrice’, de l’époque latine à nos jours », Femmes et langues, numéro spécial de la revue Sêméion. Travaux de sémiologie, Anne-Marie HOUDEBINE (dir.), 2008, pp. 53-62, réédition numérique, http://siefar.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Histoire-dautrice-A_-Evain.pdf , SIEFAR (Société Internationale pour l'Étude des Femmes de l'Ancien Régime).

Hertz, Ellen, (2002) « Le matrimoine » dans M.-O. GONSETH, J. HAINARD et KAEHR R. (dir.), Le musée cannibale, Neuchâtel, Musée d’ethnographie, p. 153-168.

Moreau, Antoine, (2018) « Matrimoine, le patrimoine à l’ère de l’internet et du numérique ». Hyperheritage International Symposium (HIS) 5, Patrimoines et design d’expérience à l’ère numérique., May, Constantine, Algérie.

Riuz, Geneviève, (2020) « Non, “matrimoine” n’est pas un néologisme », Hémisphères, revue suisse de la recherche et de ses applications, no18.

—

Les propositions (10 lignes maximum, comprenant un titre, un résumé et des mots-clés, en français ou en espagnol) doivent être envoyées au plus tard le 15 novembre 2025 aux adresses suivantes : carole.filliere@univ-tlse2.fr, emilie.guyard@univ-pau.fr et aflorenchie@u-bordeaux-montaigne.fr

Les articles sélectionnés sur proposition seront à envoyer aux mêmes adresses pour le 1er mars 2026.

Responsable :

Amélie Florenchie, Emilie Guyard, Carole Fillière

Url de référence :

https://interfas.univ-tlse2.fr/lamaindethot/

https://www.fabula.org/actualites/128303/la-main-de-thot-2026-n-14-re-traduire-les-autrices.html

#metaglossia_mundus

"Two Welsh councils could work closer together on translating documents into Welsh, including using AI technology.

Councils, and other public bodies, are legally required to produce documents and provide services in Welsh.

Monmouthshire County Council looked at alternatives to its current use of external translators as part of its budget-setting process due to increased demand which has seen spending on translations exceed the allocated budget.

Its performance and overview scrutiny committee was told total costs, to the council of providing Welsh language services, was £226,940 last year.

But it wasn’t clear if that figure only covered translations or also the cost of two officers. Equalities and Welsh language manager, Pennie Walker, described the “major costs” as translations and her salary, and that of the Welsh language officer, while ensuring compliance with Welsh language standards is the “day to day responsibility of all officers”.

Nia Roberts, the Welsh language officer, said closer working with neighbouring Torfaen Borough Council is currently “the most desired option” to save on translation costs and it is already using AI, also known as artificial intelligence.

Ms Roberts said Monmouthshire currently uses external translators, who may already be using AI systems, but that wouldn’t produce a saving for the council as it currently pays by the word.

She said AI would “never produce 100 per cent accurate translations” and added: “It will need to have some kind of proof reading to make sure the translation is accurate.”

Rogiet Labour member Peter Strong had asked if a favoured option had emerged from the ongoing review that has also considered continuing with external translators and setting up its own in-house translation team.

Ms Roberts said joining with Torfaen “looks the more desirable” and said: “Torfaen is similar to Monmouthshire in the type of documents to be translated.”

She also said Torfaen uses technology that memorises words it has previously translated which would help with the consistency of documents.

Proof-reading required

Torfaen councillors, who were presented with their annual report on how their council is complying with Welsh language standards at their June meeting, were told AI has helped with increasing translations by 24 per cent on the previous year.

Torfaen’s Welsh language officer Alan Vernon-Jones cautioned: “Everything needs to be proof read by a competent Welsh speaker.”

Monmouthshire’s review of translations has also given “careful consideration” to the potential impact on small Welsh businesses, quality and timeliness, and the need to maintain full compliance with the Welsh language standards...

On AI Cllr Neill, who chairs the committee, said: “It sounds like AI doesn’t speak Welsh very well. The ‘tech bros’ are going to have to do some more work on it.”"

https://nation.cymru/news/councils-could-use-ai-to-translate-documents-into-welsh/

#metaglossia_mundus

"Manx Care says it's spent just over £23,000 on translators since 2021.

It gave the figures in response to a Freedom of Information request, saying the translators were needed to help patients with poor English.

The figures show this so far year, £1,255 has been spent on such services.

But the organisation hasn't provided any details about whether extra translators are needed during motorsport periods when the Island sees thousands of foreign visitors."

https://www.three.fm/news/isle-of-man-news/translators-paid-23000-by-manx-care-in-five-years/

#metaglossia_mundus

European literary organizations see the Archipelagos project as a way to identify and promote translations from lesser-used languages.

"Navigation

Europe’s ‘Archipelagos’ Project: Supporting Translators and Lesser-Used Languages

In News by Jaroslaw AdamowskiJune 16, 2025

European literary organizations see the Archipelagos project as a way to identify and promote translations from lesser-used languages.

Participants in a 2024 Berlin meeting of Ukrainian literature translators. Image: Atlas-CITL

By Jarosław Adamowksi | @JaroslawAdamows

Open for ‘Scouting Residency’ Applications

Today (June 16), a collective open call for scouting residencies for literary translators is announced by European literary organizations working to promote the Archipelagos project. The program is designed to unearth the diversity of literary voices in Europe by offering residencies to literary translators working in lesser-used languages.

Led by France’s Atlas-Citl (International College of Literary Translators), the Archipelagos project has eight main partners from seven countries. They work in 10 languages. There are four associated partners that support the project with dedicated activities such as a summer school for booksellers, seminars for librarians, and translation workshops.

The Archipelagos project will offer residencies over the next three years for more than 100 literary translators throughout Europe. There are also to be 10 translation workshops expected to attract as many as 150 participants.

The main partners of the project include:

Czechia’s Czechlit;

Bulgaria’s Next Page Foundation;

France’s IReMMO;

Germany’s Literarisches Colloquium Berlin;

Poland’s College of Eastern Europe;

Spain’s ACE Traductores; and

The Ukrainian Book Institute.

‘The Translator’s Scouting Activity’

Julie Duthey, who is responsible for communication at Atlas, tells Publishing Perspectives that the Archipelagos project was created to help develop linguistic diversity in Europe’s translated literature marketplace. The key goal is to highlight how literary translators facilitate the discovery of less translated literatures.

Julie Duthey

“Literature written in European languages other than English,” Duthey says, “is in the minority in this market. According to the Translators on the Cover report, around 60 percent of books translated each year into French, German, or Italian are translated out of English.

“A little-known and often unpaid part of the translator’s work consists of finding new voices,” she says, “by funding residencies dedicated to the translator’s scouting activity. Archipelagos recognizes and supports this research. We support translators from all over Europe in their scouting activity, offering them the opportunity to prepare a portfolio and build trusting relationships with publishers.”

During their residencies, the project’s participants can work on synopsis and translation excerpts of the books they discover, and their work can be found on the project’s site.

“The final beneficiaries of this program,” Duthey says, “are the publishers, who can raise what we call ‘unseen stories,’ giving visibility to diverse experiences of the world, and new perspectives.”

Atlas, the French organization, plays an overarching role in the project, according to Duthey

“As a lead partner,” she says, “we coordinate the project activities, communications, and deliverables with and for all partners. As one of the residency hosts, we provide successful candidates with an accommodation at the Collège International des Traducteurs Littéraires or elsewhere in Europe, depending on their project, and a bursary to cover their expenses.

“We bring together translators for translation and editorial workshops. We highlight their discoveries through public readings and a podcast series.”

‘Empowering Translators as Scouts and Connectors’

Established in 2024, Archipelagos is a three-year project. Between 2024 and 2026, the initiative is expected to support more than 25 European languages, through its scouting residencies and workshops.

Monica Dimitrova

Monica Dimitrova, the communications manager at Next Page Foundation, tells Publishing Perspectives that Archipelagos is “more than a literary project. It’s a cultural act of resistance against linguistic marginalization and a step toward a more inclusive, interconnected European identity through literature.

“By empowering translators as scouts and connectors, it not only uncovers new literary treasures but also builds lasting bridges between communities, languages, and readers.”

Some of the planned professional and public events to be held this year and in 2026 include: a workshop for translators translating from Lithuanian planned for October in Vilnius; and Adab, a festival on Arabic literatures in December in Paris.

“Our next big step is the last open call for a scouting residency in 2026,” Duthey says. “Translators will be able to apply until October 5. Literary translators from across Europe can apply for residencies.”"

https://publishingperspectives.com/2025/06/europes-archipelagos-project-supporting-translators-and-lesser-used-languages/

#metaglossia_mundus

"Agence de presse Xinhua | 16. 06. 2025

Vêtu d'une veste traditionnelle Tang, complétée par une cravate ornée d'une exquise calligraphie chinoise, Joël Bellassen ne se contente pas de parler couramment le chinois : il vit et respire cette langue.

Depuis des décennies, ce Français passe sa vie à apprendre, à enseigner et à promouvoir la langue chinoise, dont il a fait une partie de son identité. Tout a commencé par un vif intérêt pour les caractères de la langue, qu'il a découvert pour la première fois en passant devant des restaurants chinois.

"Les caractères chinois ne sont pas seulement un outil", déclare-t-il à Xinhua. "Ils sont l'ADN de la culture chinoise".

M. Bellassen a été le premier inspecteur général de chinois au ministère de l'Education nationale et a dirigé l'élaboration du tout premier programme d'enseignement complet de cette langue, qui est actuellement utilisé dans toute la France.

Récemment, M. Bellassen est retourné à Beijing pour une visite académique organisée par le Centre mondial de sinologie de l'Université des langues et Cultures de Beijing, son alma mater, où il a approfondi ses études de chinois après avoir obtenu son diplôme de premier cycle en langue chinoise à Paris.

En 1969, M. Bellassen, alors âgé de 19 ans, a choisi de se spécialiser en chinois à l'Université Paris 8. Un choix inhabituel en France à l'époque, compte tenu des perspectives de carrière limitées associées à cette langue.

"C'était un défi", se souvient-il. "Ce qui m'a fasciné, c'est que j'apprenais quelque chose que personne d'autre n'osait faire".

En peu de temps, il est devenu passionné. Il a commencé à tracer des caractères et à enseigner à ses camarades de classe dès qu'il apprenait de nouveaux mots. Ce qui lui a même valu le surnom de "Chinois".

Pour M. Bellassen, la distance a toujours été synonyme d'opportunité.

"Des années 1970 à aujourd'hui, j'ai visité la Chine des centaines de fois", explique-t-il. "Chaque visite m'a permis d'approfondir ma compréhension de la culture chinoise. Plus j'en apprends, plus je réalise à quel point les caractères chinois sont indissociables de l'identité culturelle de la Chine".

Cette compréhension s'est davantage approfondie lors de sa visite des ruines de Yin à Anyang, dans la province chinoise du Henan (centre), en avril. Sur place, il y a vu les inscriptions sur os d'oracle, qui conservent des traces de la langue écrite chinoise d'il y a 3.000 ans.

Découvertes pour la première fois en 1899, les inscriptions sur os d'oracle font partie des quatre caractères les plus anciens du monde et ont été inscrites au Registre de la mémoire du monde de l'UNESCO.

"J'ai eu l'impression de faire un pèlerinage", indique M. Bellassen, en réfléchissant aux racines culturelles profondes de ces symboles anciens.

"Pour moi, les caractères chinois sont plus que des mots ; ce sont des réminiscences culturelles qui aident à expliquer ce qui semble impossible à traduire".

Selon lui, les caractères chinois possèdent même une dimension poétique.

"J'aime la poésie chinoise ancienne et les expressions idiomatiques à quatre caractères", explique M. Bellassen. "Ils résument des idées philosophiques profondes et complexes en seulement quelques caractères."

L'une des possessions les plus précieuses de M. Bellassen est une cravate dont les motifs sont inspirés du travail au pinceau du calligraphe chinois du XIVe siècle Zhao Mengfu. Offerte par un ami chinois, elle l'a accompagné dans d'innombrables déplacements universitaires.

"Les caractères eux-mêmes ont une beauté esthétique", précise-t-il, ajoutant qu'il s'est exercé à écrire son caractère chinois préféré, "wo", qui signifie "je", pendant des années.

M. Bellassen estime que l'apprentissage de l'écriture chinoise présente des avantages cognitifs uniques, en particulier pour les jeunes enfants.

"L'écriture des caractères aide à développer la coordination motrice, la conscience spatiale et le sens de l'organisation", explique-t-il. "Chaque trait a son importance ; chacun doit trouver sa place. C'est une façon différente d'entraîner à la fois la main et l'esprit".

De retour en France en 1975 après un programme d'échange de deux ans à Beijing, M. Bellassen a consacré les cinq décennies suivantes à introduire l'enseignement du chinois dans les salles de classe en France.

L'ouvrage intitulé "Méthode d'initiation à la langue et à l'écriture chinoises", compilé par ses soins, est devenu l'un des manuels de chinois les plus utilisés en France.

"La Chine a connu une modernisation rapide au cours des cinquante dernières années, mais ce qui est particulièrement remarquable, c'est le nombre de pratiques culturelles qui ont perduré", indique-t-il.

Un comportement artistique l'a étonné : dans un parc de Shanghai, il a pu voir un homme utiliser un grand pinceau, trempé dans l'eau, pour écrire des calligraphies sur le sol, appelées "dishu" en chinois. Généralement, les caractères sont amenés à disparaître lorsque l'eau sèche.

"C'est un phénomène culturel typiquement chinois", déclare-t-il. "Il reflète l'essence culturelle profonde de la Chine".

Son amour pour la culture chinoise va bien au-delà de la langue. Il est tombé amoureux de la cuisine chinoise - les boulettes de crevettes et les pattes de poulet de la cuisine cantonaise restent ses plats préférés. "Les Chinois et les Français accordent tous deux une grande attention à la nourriture", observe-t-il.

M. Bellassen espère depuis longtemps que davantage de personnes dans son propre pays apprendront à connaître la culture chinoise, en particulier la beauté des caractères chinois.

En 2019, à l'occasion du 55e anniversaire de l'établissement des relations diplomatiques entre la Chine et la France, il a participé au lancement du premier Festival des caractères chinois à Paris, qui mettait à l'honneur l'art du "dishu".

"J'espère que le festival deviendra un événement où les gens pourront découvrir de plus près la beauté des caractères chinois", ajoute-t-il. "Sans eux, je ne serais pas ce que je suis aujourd'hui"."

http://french.china.org.cn/china/txt/2025-06/16/content_117929959.htm

#metaglossia_mundus

"Le 16 juin. 2025 à 03h00 (TU) à jour le 16 juin. 2025 à 15h20 (TU)

Une initiative d'un collectif pour enseigner le patrimoine littéraire dans les langues régionales de France a reçu lundi un soutien inattendu, celui du secrétaire perpétuel de l'Académie française, Amin Maalouf.

M. Maalouf, écrivain franco-libanais, a été élu en 2023 à la tête d'une institution qui a pour mission de veiller au rayonnement et à l'intégrité de la langue française...

Ce dernier a écrit au Premier ministre, François Bayrou, et à la ministre de l'Éducation nationale, Elisabeth Borne, pour proposer un corpus d'œuvres en langues régionales destiné aux professeurs, afin de sensibiliser à la "richesse de la production littéraire" dans d'autres langues que le français.

"M. Maalouf, comme nous-mêmes, a la conviction qu'il est nécessaire que les élèves de France aient connaissance de ces trésors culturels", écrit le collectif à M. Bayrou, qui lui-même parle le béarnais.

"Je veux souligner à quel point le soutien d'Amin Maalouf est quelque chose de révolutionnaire. (...) Pour nous, c'est une chance extraordinaire...", a souligné lors d'une visioconférence lundi l'un des membres du collectif, le journaliste Michel Feltin-Palas.

"Ce qui le touche, c'est que notre démarche est universelle. Qu'est-ce qui est séparatiste? C'est le fait qu'il n'y aurait qu'un petit Basque qui connaîtrait la littérature basque, un petit Alsacien qui connaîtrait la littérature alsacienne. Alors que notre démarche s'adresse à tout élève français", a ajouté une autre membre,... Céline Piot.

Le Collectif pour les littératures en langues régionales a constitué, avec l'aide de spécialistes, un recueil intitulé "Florilangues" avec 32 textes, en langue originale, de l'alsacien au tahitien, en passant par le basque ou le corse, traduits en français. Il répond à une demande de M. Maalouf.

On y trouve entre autres un poème en provençal de Frédéric Mistral (prix Nobel de littérature 1904), "Mirèio", une chronique en breton de Pierre-Jakez Hélias, "Bugale ar Republik", un court récit en créole martiniquais de Raphaël Confiant, "Bitako-a", ou une chanson en picard d'Alexandre Desrousseaux, "Canchon dormoire" (plus connue sous le nom de "P'tit Quinquin").

Une attention a été portée à la place des autrices, même si elles sont en minorité dans Le recueil.

L'ouvrage doit paraître en 2026 chez un éditeur spécialiste de l'occitan, L'Aucèu libre, pour une diffusion nationale.

"Il ne s'agit pas de donner des cours de langues régionales mais de présenter des œuvres issues des littératures en langues régionales, que ce soit en français ou en version bilingue", précise le collectif.

Pour lui..., les élèves aborderaient des langues issues d'autres régions que la leur. "Pourquoi seuls les élèves antillais apprendraient-ils qu'il existe une littérature en créole?", demande le collectif."

https://information.tv5monde.com/culture/un-soutien-inattendu-pour-les-langues-regionales-amin-maalouf-de-lacademie-francaise

#metaglossia_mundus

"Un soutien inattendu pour les langues régionales: Amin Maalouf, de l'Académie française

Un soutien inattendu pour les langues régionales: Amin Maalouf, de l'Académie française

16/06/2025

Une initiative d'un collectif pour enseigner le patrimoine littéraire dans les langues régionales de France a reçu lundi un soutien inattendu, celui du secrétaire perpétuel de l'Académie française, Amin Maalouf.

M. Maalouf, écrivain franco-libanais, a été élu en 2023 à la tête d'une institution qui a pour mission de veiller au rayonnement et à l'intégrité de la langue française.

Mais il soutient la démarche du Collectif pour les littératures en langues régionales, qui suggère un enseignement de ce type au collège ou au lycée, a indiqué ce collectif à l'AFP.

Ce dernier a écrit au Premier ministre François Bayrou et à la ministre de l'Éducation Elisabeth Borne pour proposer un corpus d'oeuvres en langues régionales destiné aux professeurs, afin de sensibiliser à la "richesse de la production littéraire" dans d'autres langues que le français.

"M. Maalouf -comme nous-mêmes- a la conviction qu'il est nécessaire que les élèves de France aient connaissance de ces trésors culturels", écrit ce collectif à M. Bayrou, qui lui-même parle le béarnais.

Le Collectif pour les littératures en langues régionales a constitué, avec l'aide de spécialistes, un recueil intitulé "Florilangues" avec 32 textes, en langue originale, de l'alsacien au tahitien, en passant par le basque ou le corse, traduits en français.

On y trouve entre autres un poème en provençal de Frédéric Mistral (prix Nobel de littérature 1904), "Mirèio", une chronique en breton de Pierre-Jakez Hélias, "Bugale ar Republik", un court récit en créole martiniquais de Raphaël Confiant, "Bitako-a", ou une chanson en picard d'Alexandre Desrousseaux, "Canchon dormoire" (plus connue sous le nom de "P'tit Quinquin").

"Il ne s'agit pas de donner des cours de langues régionales mais de présenter des oeuvres issues des littératures en langues régionales, que ce soit en français ou en version bilingue", précise le collectif.

Pour lui, idéalement, les élèves aborderaient des langues issues d'autres régions que la leur. "Pourquoi seuls les élèves antillais apprendraient-ils qu'il existe une littérature en créole ?", demande ce collectif, qui présente son initiative à la presse lors d'une visioconférence lundi après-midi."

https://www.linfodurable.fr/un-soutien-inattendu-pour-les-langues-regionales-amin-maalouf-de-lacademie-francaise-51414

#metaglossia_mundus

"For the first time, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), has produced a Mandarin translated podcast of popular original ABC Kids audio series Soundwalks. The immersive and sensory-rich audio experience for children offers a variety of guided relaxations featuring the soothing sounds of Australian nature and is available on ABC Asia’s audio tab, ABC Kids listen as well as on third-party podcast platforms.

Hosted by bilingual performer, MC, voice and speech teacher Nikki Zhao, Soundwalks promotes mindfulness, calm and curiosity, helping children manage their emotions. The 10-episode series offers a gentle and playful introduction to language and can be used as an educational resource to support bilingual development in children.

ABC International Head Claire M. Gorman said: “This exciting new series will delight international and domestic audiences across the Mandarin-speaking diaspora and marks an important expansion of ABC International’s content offering via the newly launched ABC Asia audio tab.”

Executive Producer ABC Kids Audio Veronica Milsom said: “We are thrilled to be expanding our audio offering with this beautiful audio series that acts as a source of comfort and support for children and their guardians. Creating accessible and inclusive content is a key priority for our programming and by delivering this series in Mandarin we hope that even more children will be able to access the health and wellbeing benefits of this series.”

WAYS TO LISTEN:

Soundwalks in Mandarin is available wherever you get your podcasts or via the ABC Asia Audio tab or ABC Kids listen.

For all media enquiries, contact Annalise Ramponi, Marketing and Communications Coordinator, ABC International

Ramponi.annalise@abc.net.au

We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Australians and Traditional Custodians of the lands where we live, learn and work. "

Posted 13 Jun 202513 Jun 2025

https://www.abc.net.au/about/media-centre/publicity-media-room/abc-launches-mandarin-translation-childrens-podcast-soundwalks/105412570

#metaglossia_mundus

"La littérature sinophone au-delà des frontières chinoises : entretien avec l’auteure Zhang Lijia

Les auteurs doivent être libres de créer pour mieux raconter l’histoire de la Chine

Written (English) by

Filip Noubel

Traduit (Français) par

Rodrigue Macao

Lire cet article en українська, Español, English

Original posted 25/04/2025

Traduction publiée le 12/06/2025

Zhang Lijia. Photo utilisée avec permission.

Près de 50 millions de Chinois ne vivent pas en Chine. Cette population, souvent réduite à un simple acteur économique, est en vérité très active dans les domaines médiatiques et culturels, dont la littérature, particulièrement appréciée des citoyens de la diaspora chinoise qui peuvent écrire en chinois ou dans la langue de leur pays hôte.

Afin de comprendre les nuances qui entourent la littérature de la diaspora chinoise, Global Voices s’est entretenu avec Zhang Lijia (张丽佳), ancienne employée d’une usine de roquettes devenue auteure analysant la société, est née en Chine et alterne aujourd’hui une vie entre Londres et Pékin. Elle est l’auteure du mémoire « Socialism Is Great! » et du roman « Lotus », une œuvre abordant le sujet de la prostitution dans la Chine contemporaine. Son prochain ouvrage, un roman historique, racontera la vie de Qiu Jin, la première féministe et révolutionnaire chinoise à l’aube du 20 ᵉ siècle, souvent appelée « la Jeanne d’Arc de Chine ».

Filip Noubel (FN) : Ressentez-vous une certaine liberté lorsque vous écrivez dans une langue que vous avez apprise tard dans votre vie ? Est-ce que c’est une question d’autocensure ? Pensez-vous que cela vous permet d’étendre votre style et d’expérimenter avec le processus d’écriture ?

Traduction Citation d'origine

Zhang Lijia (ZLJ) : En tant qu’auteure chinoise ayant grandi en Chine et n’ayant jamais parlé que le chinois, il est vrai qu’écrire en anglais fut, étonnamment, assez libérateur. Politiquement parlant, je suis plus libre lorsque j’écris pour un public international. Cela me permet de contourner la censure chinoise, qui ne sert qu’à étouffer la créativité. En effet, je pense que cette censure est l’une des raisons pour laquelle la scène littéraire chinoise n’est pas aussi vibrante et dynamique qu’elle pourrait l’être.

Créativement parlant, écrire en anglais offre une liberté totalement différente. Puisque l’anglais n’est pas ma langue natale, je ressens un certain confort à tester les structures, les formes et les différents styles de la langue. Cette méconnaissance de la langue m’a permis d’ouvrir de nombreuses portes et de découvrir de nouvelles perspectives. L’anglais, en tant que langue adoptée, me permet d’explorer et d’articuler mes pensées d’une manière que je pensais impossible en chinois. Par exemple, dans le mémoire « Socialism Is Great! », j’ai écrit une scène de sexe bien plus explicite que ce que je me serais permis de créer en chinois, puisque les nuances linguistiques et culturelles auraient demandé un peu plus de retenue.

Écrire en anglais m’a permis d’ouvrir de nombreuses voies, tant dans une exploration créative que dans une émancipation personnelle.

FN : Écrivez-vous encore en chinois ? Comment décririez-vous la relation qui se crée entre ses deux langues dans votre processus créatif ?

Traduction Citation d'origine

ZLJ : J’écris rarement en chinois ces temps-ci, sauf lorsque je suis invité à participer à des publications chinoises. Le chinois est une langue très riche et expressive, autant culturellement qu’historiquement. Mais quand j’écris en anglais, je m’amuse à insérer des termes datés et des expressions classiques afin de rendre ma prose plus élégante, comme si je donnais un second souffle à des phrases oubliées. C’est une manière d’amener un vent de fraîcheur à une langue et de se connecter à ses racines enfouies.

L’anglais et le chinois ne servent pas le même but dans mon processus créatif. Je me sers principalement de l’anglais pour raconter une histoire, c’est une langue qui me permet de briser mes chaînes et de tester de nouvelles choses. Mais le chinois reste tout de même la langue de monde intérieur, elle est liée à ma mémoire et à mon identité. Lorsque j’écris en anglais, c’est comme si je construisais un pont qui relie deux cultures, je traduis plus que des mots, je traduis des expériences, des émotions et toute une culture.

FN : On parle souvent de littérature sinophone transcendant les barrières linguistiques et géographiques, Xiaolu Guo, Ha Jin, Dan Sijie, Yan Geling, sans vous oublier, bien sûr. Pensez-vous qu’un tel genre de littérature existe réellement ? Si oui, quelle en est la définition ?

Traduction Citation d'origine

ZLJ : Effectivement, je pense qu’il est tout à fait valide de considérer la littérature sinophone globale comme un genre vivant. J’imagine que ce terme fait référence aux œuvres écrites dans des langues chinoises (comme le mandarin ou le hokkien) ou écrites par des auteurs d’origines chinoises qui ne vivent pas en Chine continentale. Ces œuvres abordent une large variété de thèmes et de situations qui reflètent la complexité d’interagir avec une langue, une identité et même avec la géopolitique intradiaspora chinoise.

Ce qui définit ce genre de littérature, c’est sa multiplicité. Elle n’est pas limitée par la géographie, par l’usage d’un style, ni par la perspective. Non, ce genre capture la réalité vécue par les communautés chinoises éparpillées à travers le monde, il explore des thèmes comme l’immigration, l’identité et le mélange culturel. Il redéfinit la notion de « littérature chinoise » en mettant l’accent sur la pluralité des voix chinoises.

En pleine ère de globalisation, je dois avouer que j’apprécie la reconnaissance de la littérature sinophone dans le monde entier. Cela représente une certaine opportunité de pouvoir approfondir nos connaissances de la culture chinoise et de ses fonctions au-delà des frontières nationales. Cela encourage une discussion sur le postcolonialisme et sur l’interconnexion mondiale.

À ce propos, la campagne « bien raconter l’histoire de la Chine » lancée par Xi Jinping vise à projeter une image favorable de la Chine dans l’esprit des étrangers via le soft Power. Si cette idée peut paraître louable, pour qu’elle réussisse, il faudrait que les auteurs soient libres d’écrire ce qu’ils souhaitent. À l’heure actuelle, la censure est encore bien trop présente pour que les auteurs puissent « bien raconter l’histoire de la Chine ». Si nous ne pouvons pas créer librement, ce projet ne sera rien de plus qu’une éternelle chimère. J’ai partagé cette opinion dans l’article suivant : Tell China’s Story Well: Its Writers Must Be Free Enough to Do So.

FN : Quels sont les auteurs chinois qui vous ont le plus influencés ? Qu’en est-il des auteurs qui ne sont pas chinois ?

Traduction Citation d'origine

ZLJ : Parmi les auteurs chinois, je pense que Cao Xueqin, auteur de « Le Rêve dans le pavillon rouge », est celui qui m’a le plus influencé. La manière dont il partage la complexité des relations familiales et sociales, le tout dans un décor de monde aristocratique sur le point de s’écrouler, n’a jamais été égalée, que ce soit sur le plan émotionnel ou littéraire. Je pourrais également cite Lu Xun comme une autre de mes influences. Ses observations tranchantes sur la société chinoise révèlent une compréhension de la psyché chinoise qui n’a jamais été surpassée.

Parmi les auteurs étrangers, je pense que Tolstoï surpasse tous les autres. Ses histoires grandioses écrites sur fond de récits sociaux et historiques sont tout simplement fascinantes, et pourtant il ne perd jamais de vue les petits détails qui rendent ses personnages humains.

J’admire également et grandement Arundhati Roy, surtout son roman « Le Dieu des Petits Riens ». Sa prose lyrique, son imagerie riche, mais aussi la manière poignante qu’elle a d’explorer les difficultés sociales et personnelles résonnent véritablement avec moi, elle inspire la façon dont je raconte mes histoires."

https://fr.globalvoices.org/2025/06/12/295214/

#metaglossia_mundus

"Avec Enfant, ne pleure pas, Ngugi wa Thiong'o a offert l’un des récits les plus poignants de la littérature africaine. Plus de 60 ans après sa parution, ce roman demeure un puissant témoignage sur la colonisation, la résistance et la quête d’émancipation. Le décès récent de l’écrivain kényan est l’occasion pour Samir Belahsen de revenir sur cette œuvre fondatrice, universelle par sa portée, ancrée dans l’histoire mais toujours résonnante aujourd’hui.

“L'instruction est le seul moyen de libération.”

“Le soleil brille toujours après une nuit sombre.”

Ngugi wa Thiong`o

Le décès de Ngugi wa Thiong'o, connu sous le nom de James Ngugi, était annoncé le 28 mai dernier. Ecrivain Kenyan né en 1938, il avait fait ses premiers pas en anglais, avant de faire le choix d'écrire dans sa langue maternelle : le gikuyu. Il a écrit des romans, des pièces de théâtre et des nouvelles, s'est tourné é également vers la littérature pour enfants. Wa Thiong a émigré aux Etats -Unis après avoir passé plus d’un an en prison au Kenya. Il y enseignera dans plusieurs universités, A Yale puis à l'Université de New York et à l'Université de Californie.

Décoloniser l’esprit : Une raison d’être

C’était sa raison d’écrire et le titre de son recueil d’essais publié en 1986, peut être aussi sa raison d’être…

Il est considéré comme son œuvre majeure, il y défend la décolonisation linguistique.