Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Charles Tiayon

November 4, 2011 8:32 PM

|

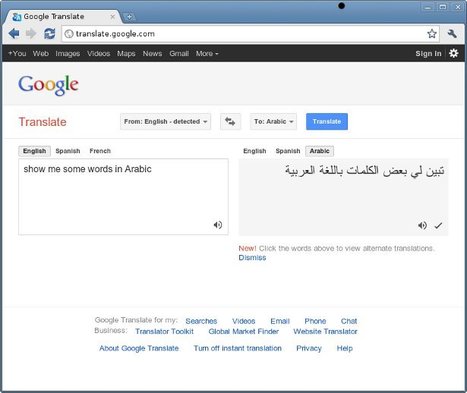

Google is shutting down its free Translation API on 1 December, while Microsoft's remains free.

Researchers across Africa, Asia and the Middle East are building their own language models designed for local tongues, cultural nuance and digital independence

"In a high-stakes artificial intelligence race between the United States and China, an equally transformative movement is taking shape elsewhere. From Cape Town to Bangalore, from Cairo to Riyadh, researchers, engineers and public institutions are building homegrown AI systems, models that speak not just in local languages, but with regional insight and cultural depth.

The dominant narrative in AI, particularly since the early 2020s, has focused on a handful of US-based companies like OpenAI with GPT, Google with Gemini, Meta’s LLaMa, Anthropic’s Claude. They vie to build ever larger and more capable models. Earlier in 2025, China’s DeepSeek, a Hangzhou-based startup, added a new twist by releasing large language models (LLMs) that rival their American counterparts, with a smaller computational demand. But increasingly, researchers across the Global South are challenging the notion that technological leadership in AI is the exclusive domain of these two superpowers.

Instead, scientists and institutions in countries like India, South Africa, Egypt and Saudi Arabia are rethinking the very premise of generative AI. Their focus is not on scaling up, but on scaling right, building models that work for local users, in their languages, and within their social and economic realities.

“How do we make sure that the entire planet benefits from AI?” asks Benjamin Rosman, a professor at the University of the Witwatersrand and a lead developer of InkubaLM, a generative model trained on five African languages. “I want more and more voices to be in the conversation”.

Beyond English, beyond Silicon Valley

Large language models work by training on massive troves of online text. While the latest versions of GPT, Gemini or LLaMa boast multilingual capabilities, the overwhelming presence of English-language material and Western cultural contexts in these datasets skews their outputs. For speakers of Hindi, Arabic, Swahili, Xhosa and countless other languages, that means AI systems may not only stumble over grammar and syntax, they can also miss the point entirely.

“In Indian languages, large models trained on English data just don’t perform well,” says Janki Nawale, a linguist at AI4Bharat, a lab at the Indian Institute of Technology Madras. “There are cultural nuances, dialectal variations, and even non-standard scripts that make translation and understanding difficult.” Nawale’s team builds supervised datasets and evaluation benchmarks for what specialists call “low resource” languages, those that lack robust digital corpora for machine learning.

It’s not just a question of grammar or vocabulary. “The meaning often lies in the implication,” says Vukosi Marivate, a professor of computer science at the University of Pretoria, in South Africa. “In isiXhosa, the words are one thing but what’s being implied is what really matters.” Marivate co-leads Masakhane NLP, a pan-African collective of AI researchers that recently developed AFROBENCH, a rigorous benchmark for evaluating how well large language models perform on 64 African languages across 15 tasks. The results, published in a preprint in March, revealed major gaps in performance between English and nearly all African languages, especially with open-source models.

Similar concerns arise in the Arabic-speaking world. “If English dominates the training process, the answers will be filtered through a Western lens rather than an Arab one,” says Mekki Habib, a robotics professor at the American University in Cairo. A 2024 preprint from the Tunisian AI firm Clusterlab finds that many multilingual models fail to capture Arabic’s syntactic complexity or cultural frames of reference, particularly in dialect-rich contexts.

Governments step in

For many countries in the Global South, the stakes are geopolitical as well as linguistic. Dependence on Western or Chinese AI infrastructure could mean diminished sovereignty over information, technology, and even national narratives. In response, governments are pouring resources into creating their own models.

Saudi Arabia’s national AI authority, SDAIA, has built ‘ALLaM,’ an Arabic-first model based on Meta’s LLaMa-2, enriched with more than 540 billion Arabic tokens. The United Arab Emirates has backed several initiatives, including ‘Jais,’ an open-source Arabic-English model built by MBZUAI in collaboration with US chipmaker Cerebras Systems and the Abu Dhabi firm Inception. Another UAE-backed project, Noor, focuses on educational and Islamic applications.

In Qatar, researchers at Hamad Bin Khalifa University, and the Qatar Computing Research Institute, have developed the Fanar platform and its LLMs Fanar Star and Fanar Prime. Trained on a trillion tokens of Arabic, English, and code, Fanar’s tokenization approach is specifically engineered to reflect Arabic’s rich morphology and syntax.

India has emerged as a major hub for AI localization. In 2024, the government launched BharatGen, a public-private initiative funded with 235 crore (€26 million) initiative aimed at building foundation models attuned to India’s vast linguistic and cultural diversity. The project is led by the Indian Institute of Technology in Bombay and also involves its sister organizations in Hyderabad, Mandi, Kanpur, Indore, and Madras. The programme’s first product, e-vikrAI, can generate product descriptions and pricing suggestions from images in various Indic languages. Startups like Ola-backed Krutrim and CoRover’s BharatGPT have jumped in, while Google’s Indian lab unveiled MuRIL, a language model trained exclusively on Indian languages. The Indian governments’ AI Mission has received more than180 proposals from local researchers and startups to build national-scale AI infrastructure and large language models, and the Bengaluru-based company, AI Sarvam, has been selected to build India’s first ‘sovereign’ LLM, expected to be fluent in various Indian languages.

In Africa, much of the energy comes from the ground up. Masakhane NLP and Deep Learning Indaba, a pan-African academic movement, have created a decentralized research culture across the continent. One notable offshoot, Johannesburg-based Lelapa AI, launched InkubaLM in September 2024. It’s a ‘small language model’ (SLM) focused on five African languages with broad reach: Swahili, Hausa, Yoruba, isiZulu and isiXhosa.

“With only 0.4 billion parameters, it performs comparably to much larger models,” says Rosman. The model’s compact size and efficiency are designed to meet Africa’s infrastructure constraints while serving real-world applications. Another African model is UlizaLlama, a 7-billion parameter model developed by the Kenyan foundation Jacaranda Health, to support new and expectant mothers with AI-driven support in Swahili, Hausa, Yoruba, Xhosa, and Zulu.

India’s research scene is similarly vibrant. The AI4Bharat laboratory at IIT Madras has just released IndicTrans2, that supports translation across all 22 scheduled Indian languages. Sarvam AI, another startup, released its first LLM last year to support 10 major Indian languages. And KissanAI, co-founded by Pratik Desai, develops generative AI tools to deliver agricultural advice to farmers in their native languages.

The data dilemma

Yet building LLMs for underrepresented languages poses enormous challenges. Chief among them is data scarcity. “Even Hindi datasets are tiny compared to English,” says Tapas Kumar Mishra, a professor at the National Institute of Technology, Rourkela in eastern India. “So, training models from scratch is unlikely to match English-based models in performance.”

Rosman agrees. “The big-data paradigm doesn’t work for African languages. We simply don’t have the volume.” His team is pioneering alternative approaches like the Esethu Framework, a protocol for ethically collecting speech datasets from native speakers and redistributing revenue back to further development of AI tools for under-resourced languages. The project’s pilot used read speech from isiXhosa speakers, complete with metadata, to build voice-based applications.

In Arab nations, similar work is underway. Clusterlab’s 101 Billion Arabic Words Dataset is the largest of its kind, meticulously extracted and cleaned from the web to support Arabic-first model training.

The cost of staying local

But for all the innovation, practical obstacles remain. “The return on investment is low,” says KissanAI’s Desai. “The market for regional language models is big, but those with purchasing power still work in English.” And while Western tech companies attract the best minds globally, including many Indian and African scientists, researchers at home often face limited funding, patchy computing infrastructure, and unclear legal frameworks around data and privacy.

“There’s still a lack of sustainable funding, a shortage of specialists, and insufficient integration with educational or public systems,” warns Habib, the Cairo-based professor. “All of this has to change.”

A different vision for AI

Despite the hurdles, what’s emerging is a distinct vision for AI in the Global South – one that favours practical impact over prestige, and community ownership over corporate secrecy.

“There’s more emphasis here on solving real problems for real people,” says Nawale of AI4Bharat. Rather than chasing benchmark scores, researchers are aiming for relevance: tools for farmers, students, and small business owners.

And openness matters. “Some companies claim to be open-source, but they only release the model weights, not the data,” Marivate says. “With InkubaLM, we release both. We want others to build on what we’ve done, to do it better.”

In a global contest often measured in teraflops and tokens, these efforts may seem modest. But for the billions who speak the world’s less-resourced languages, they represent a future in which AI doesn’t just speak to them, but with them."

Sibusiso Biyela, Amr Rageh and Shakoor Rather

20 May 2025

https://www.natureasia.com/en/nmiddleeast/article/10.1038/nmiddleeast.2025.65

#metaglossia_mundus

"Plus besoin d’aligner trois ans de cours du soir intensifs avant de créer une version en espagnol ou en anglais d’un Reel sur Instagram ! Meta vient de lancer une nouvelle fonction de traduction vocale par IA, disponible dès maintenant sur Facebook et Instagram. L’outil permet de doubler vos vidéos dans une autre langue, tout en gardant sa propre voix.

Cette fonction de doublage conserve non seulement la voix, mais aussi l’accent et le ton histoire que le résultat paraisse un minimum naturel. Cerise sur le gâteau, une option de synchronisation labiale ajuste les lèvres pour que tout colle parfaitement à la nouvelle bande-son.

Des doublages automatiques pour élargir l’audience

Pour l’instant, seuls l’anglais et l’espagnol sont concernés, mais Meta promet d’ajouter d’autres langues au fil du temps. Comme le résume Adam Mosseri, patron d’Instagram : « Beaucoup de créateurs ont une audience potentielle énorme, mais la langue est un obstacle. Si on peut les aider à franchir cette barrière, tout le monde est gagnant. »

Comment ça marche ? Cette fonction n’a rien de bien sorcier : avant de poster un Reel, il suffit de cliquer sur l’option « Traduire votre voix avec Meta AI », d’activer ou non la synchro labiale, puis de partager. La traduction s’ajoute automatiquement et peut être pré-visualisée. Pas satisfait ? Il est possible de la couper à tout moment, sans toucher à la vidéo originale. Les spectateurs verront un petit bandeau indiquant qu’il s’agit d’un contenu traduit par Meta AI, et ceux qui préfèrent les versions brutes pourront désactiver l’option dans leurs réglages.

La fonction est ouverte aux créateurs Facebook avec au moins 1.000 abonnés, ainsi qu’à tous les comptes publics sur Instagram. Et pour suivre l’efficacité du doublage, un nouvel indicateur dans les statistiques permet de voir combien de vues proviennent de chaque langue.

Meta va plus loin en autorisant les créateurs à téléverser jusqu’à 20 pistes audio doublées de leur propre voix sur un Reel. Une bonne nouvelle pour ceux qui veulent contrôler eux-mêmes leurs traductions, avant ou après publication. L’idée reste toujours la même, c’est de rendre un contenu compréhensible au-delà du cercle linguistique habituel du créateur.

Pour optimiser le résultat, Meta conseille de parler face caméra, clairement, sans couvrir sa bouche ni s’entourer de trop de bruit. L’outil ne gère que deux intervenants à la fois, donc on évitera de parler en chœur. Quant aux prochaines langues disponibles, mystère… mais il ne fait aucun doute que la liste s’allongera.

Cette nouveauté est une manière pour Meta de pousser encore plus loin l’intégration de l’IA dans ses services. Pour le pire comme pour le meilleur..."

Par Olivier le 20 août 2025 à 8h30

https://www.journaldugeek.com/2025/08/20/meta-double-les-voix-des-createurs-sur-facebook-et-instagram-avec-lia/

#metaglossia_mundus

#Metaglossia

"Abstract: This article examines the impact on legal processes of the need to use interpreters, drawing examples from refugee status determination procedures in the United Kingdom. It describes the roles played by interpreters in facilitating intercultural communication between asylum applicants and the administrative and legal actors responsible for assessing or defending their claims at the various stages of those procedures. The UK authorities' somewhat naïve expectations about the nature of the interpretation process display little understanding of the practical dilemmas that interpreters face. Much of the confusion and many of the barriers to communication created by the involvement of interpreters reflect the inherent untranslatability of particular notions, and so arise irrespective of the technical competence of the interpreters themselves. For example, dates may be reckoned using non-Gregorian calendars; terminologies for family relationships and parts of the body may be incongruent between the two languages; and there may be no exact indigenous legal equivalents to UK notions such as 'detention' or 'rape'. Different interpreters may therefore give different, though equally legitimate, translations of such terms, creating apparent 'inconsistencies' in the resulting translated accounts. Given the centrality of notions of credibility in asylum decision-making, even quite trivial divergencies over such matters may prove crucial."

Written by Anthony Good. Originally published in the International Journal for the Semiotics of Law

https://www.ein.org.uk/blog/interpretation-translation-and-confusion-refugee-status-determination-procedures

#metaglossia_mundus

#Metaglossia

Queens’ courts have a shortage of court interpreters and have seen a major reduction in their ranks over the past half decade.

"August 20, 2025

COURT INTERPRETERS PLAY A VITAL ROLE IN THE COURT SYSTEM BUT HAVE SEEN THEIR NUMBERS DIMINISH IN QUEENS, WHERE OVER 160 LANGUAGES ARE SPOKEN.

By Noah Powelson

Court interpreters provide crucial services for hundreds of New Yorkers going through the court system every day, navigating a system in a language they don’t speak. Nowhere is their job more crucial than the World’s Borough, home to the most diverse population in the United States.

But despite the need, Queens’ courts have a shortage of court interpreters and have seen a major reduction in their ranks over the past half decade.

According to New York Office of Court Administration data, Queens’ courts have lost a third of their court interpreter staff over the past five years. In 2019, there were 61 court interpreters assigned to Queens courts. Today, there are only 41 interpreters.

With the exception of a minor increase in 2023, Queens’ court interpreter staff numbers have steadily declined with no upward trends dating back to 2019.

The reason behind the drop in numbers is two-fold: the court system saw many older employees retire in the years following the pandemic, and court interpreting is a highly skilled profession that requires rigorous education and testing, making recruiting qualified candidates difficult, officials say.

The result, according to Queens court interpreters and judges who spoke to the Eagle, are regular delays and rescheduling as staff rush to ensure coverage across all hearings in a system already prone to delays and case backlogs.

In the World’s Borough, which contains at least 160 unique languages and dialects according to the World Economic Forum, the need for a wide array of interpreters is higher than anywhere else in the country. A New York City-based language documenting nonprofit known as the Endangered Language Alliance said there are as many as 800 languages spoken across the whole city, and Queens is home to more of them than any other borough.

A spokesperson for the Office of Court Administration said court leaders are aware of the interpreter shortage, and that they’ve implemented a number of policies to drive recruitment. That includes a multi-platform recruitment initiative for the Spanish Court Interpreter civil service examination, a court interpreter internship program, increased court interpreter salaries and raised rates for per diem court interpreters.

“The New York State Unified Court System is committed to expanding its pool of qualified court interpreters to meet the growing need for language access services in the Courts, incorporating a variety of recruitment strategies that include digital and media outreach, community and stakeholder engagement, interpreter pipeline development, expanded exam access, and ongoing outreach for less common but high-need languages,” the OCA spokesperson told the Eagle in a statement.

Yet with only 41 court interpreters serving the needs of all Queens courts, including Criminal, Civil, Family Court and others, slow downs and rescheduled hearings are only natural.

Two Queens judges told the Eagle they experience regular delays of 15 to 20 minutes waiting for court interpreters to be available for hearings. While that might not seem like much time, given the hundreds of cases that go through all Queens courts every day, those waiting periods can add up, the judges said.

Spanish and Mandarin are the languages most in demand in Queens by far, and make up most of the court’s interpreters. Queens Criminal Court tends to have a much higher volume of cases with quicker hearings, and it’s common for hundreds of cases to require Spanish interpretation each day.

According to the OCA, Queens Criminal Court has 22 interpreters on staff, while the Supreme Court, Criminal Term has four. Queens Family Court has the second-highest number of interpreters on staff with 10, while Queens Civil and Supreme Civil have three and two respectively.

Issues are especially apparent when an interpreter for a less common language is needed. For languages like Korean, Punjabi, Haitian or other dialects, the courts may only have one or two interpreters. At times, someone appearing in court may speak a language that the court does not have an interpreter for, in which case the courts will need to reserve a specialized interpreter from outside the borough, oftentimes virtually.

"Queens is the melting pot of the world,” a Queens judge granted anonymity told the Eagle. “If it's a very unusual language, we need to order somebody in advance."

Queens’ court staffers have access to a registry of per diem interpreters who are called in on a case-by-case basis to address language needs. An OCA spokesperson said the registry includes over 1,500 per diem interpreters in over 200 languages. OCA said this year, Queens County has had 4,782 per diem interpreter appearances in 74 languages, who have assisted 21,144 court users.

But other courts also have access to this registry, and the logistics of organizing hundreds of interpreters across the state to appear virtually naturally means gaps in service will happen. One Queens judge who was given anonymity said it’s not uncommon to adjourn a hearing until the following day without progress on the case because no interpreter was available for the day.

"Over the years, I'm encountering more specialized languages,” the Queens judge told the Eagle. “It has been getting worse."

Court staff shortages are not a Queens specific issue. Courts across the state have struggled to recruit attorneys, clerks, court officers, interpreters and all positions since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Judges have said recent efforts to modernize courtroom technology has helped the issue. Video calls have allowed interpreters from elsewhere in the state or country to appear in court remotely. Such a solution was not widely available prior to the start of the pandemic. Many courtrooms are also supplied with headsets and microphones, making it easier for multiple individuals who speak the same language to use the same interpreter.

But virtual court appearances bring their own set of problems. Remote interpretation is generally slower because of internet latency, and there is always the risk of severe lag, audio issues and general troubleshooting in the middle of the hearing. While technology can fill in some gaps, it can’t make up for additional experienced and skilled interpreters appearing in-person.

"There is no question there is a shortage,” a different Queens judge who was granted anonymity, told the Eagle. “Although they try the best they can, they are stretched thin…We have to problem solve on a daily basis.”

Despite the shortage, no one who spoke with the Eagle said the current interpreter shortage has led to the prevention of a case reaching a disposition.

Every case requires constant coordination and communication to ensure the right staff are ready and available, and if an interpreter calls out sick, that’s one more hurdle the judges and clerks need to account for as they get through the day’s work.

“We deal with it, we get through it, and those judges that are more experienced get through it faster," the judge said.

Court interpreters who spoke with the Eagle said that part of the issue with recruiting is that it’s a highly specialized profession that not many know about. Simply being bilingual isn’t enough. All potential recruits must receive a court interpretation certification from an accredited program, and pass a written and oral exam before they can be hired. The oral exam is frequently where applicants struggle.

One court interpreter in Queens Criminal Court said it takes years of practice and training to be able to quickly and accurately interpret live court hearings, especially during tense criminal trials with lots of back-and-forth arguments and people talking over each other.

"It's just really hard to find the right fit," the interpreter said. "Even if you have people that have the right skills, they still need to be knowledgeable about the various modes of interpreting.”

Sometimes, interpreters will have to be on call for two separate court parts if one of their coworkers is sick or otherwise unavailable that day. One interpreter told the Eagle that it was common for them to interpret dozens of individual cases in one morning.

Court interpreters don’t exist just for the court record; they are the literal voice for clients who cannot defend or represent themselves without one. While every judge, attorney, clerk, reporter and officer are necessary to ensure a fair justice system, court interpreters play an intimate role ensuring the voices of Queens are heard.

River Liu, a senior court interpreter at Queens Criminal Court, said his staff play a crucial role in ensuring the people of Queens feel respected when their day in court comes.

"For them, I think they do find some comfort when they have an interpreter there," Liu said. "When you are in a setting where you don't know what's going on, it's scary…Just being there for them, our presence, it helps them feel like they have their equal rights despite the language barrier."

Many court interpreters, whether they were immigrants themselves or raised by an immigrant family, grew up speaking two languages at home. For many interpreters, they were raised acutely aware of the difficulties non-native English speakers go through when navigating the intimidating and convoluted judicial system. For many, interpreters are not just impartial court staff, but their guide through likely some of the most difficult parts of their lives.

"It's a great job," Liu said. "We're the voice for the people of the court; we bridge that gap.""

https://queenseagle.com/all/2025/8/20/160-languages-41-interpreters-queens-courts-have-interpreter-shortage-leading-to-delays

#Metaglossia

#metaglossia_mundus

"Meta is rolling out an AI-powered voice translation feature to all users on Facebook and Instagram globally, the company announced on Tuesday.

The new feature, which is available in any market where Meta AI is available, allows creators to translate content into other languages so it can be viewed by a broader audience.

The feature was first announced at Meta’s Connect developer conference last year, where the company said it would pilot test automatic translations of creators’ voices in reels across both Facebook and Instagram.

Meta notes that the AI translations will use the sound and tone of the creator’s own voice to make the dubbed voice sound authentic when translating the content to a new language.

In addition, creators can optionally use a lip-sync feature to align the translation with their lip movements, which makes it seem more natural.

At launch, the feature supports translations from English to Spanish and vice versa, with more languages to be added over time. These AI translations are available to Facebook creators with 1,000 or more followers and all public Instagram accounts globally, where Meta AI is offered.

To access the option, creators can click on “Translate your voice with Meta AI” before publishing their reel. Creators can then toggle the button to turn on translations and choose if they want to include lip-syncing, too. When they click “Share now” to publish their reel, the translation will be available automatically.

Creators can view translations and lip syncs before they’re posted publicly and can toggle off either option at any time. (Rejecting the translation won’t impact the original reel, the company notes.) Viewers watching the translated reel will see a notice at the bottom that indicates it was translated with Meta AI. Those who don’t want to see translated reels in select languages can disable this in the settings menu.

Creators are also gaining access to a new metric in their Insights panel, where they can see their views by language. This can help them better understand how their content is reaching new audiences via translations — something that will be more helpful as additional languages are supported over time.

Meta recommends that creators who want to use the feature face forward, speak clearly, and avoid covering their mouth when recording. Minimal background noise or music also helps. The feature only supports up to two speakers, and they should not talk over each other for the translation to work.

Plus, Facebook creators will be able to upload up to 20 of their own dubbed audio tracks to a reel to expand their audience beyond those in English- or Spanish-speaking markets. This is offered in the “Closed captions and translations” section of the Meta Business Suite and supports the addition of translations both before and after publishing, unlike the AI feature.

Meta says more languages will be supported in the future but did not detail which ones would be next to come or when.

“We believe there are lots of amazing creators out there who have potential audiences who don’t necessarily speak the same language,” explained Instagram head Adam Mosseri in a post on Instagram. “And if we can help you reach those audiences who speak other languages, reach across cultural and linguistic barriers, we can help you grow your following and get more value out of Instagram and the platform.”

The launch of the AI feature comes as multiple reports indicate that Meta is restructuring its AI group again to focus on four key areas: research, superintelligence, products, and infrastructure."

Meta rolls out AI-powered translations to creators globally, starting with English and Spanish

Sarah Perez

10:20 AM PDT · August 19, 2025

https://techcrunch.com/2025/08/19/meta-rolls-out-ai-powered-translations-to-creators-globally-starting-with-english-and-spanish/

#Metaglossia

#metaglossia_mundus

"Intelligence Artificielle : le Maroc proche d’un exploit historique

PAR JACQUES EVRARD GBAGUIDI 15 août 2025 à 12:28

Le développement de l’Intelligence Artificielle sera désormais au cœur de l’université internationale du Maroc. Ce complexe du savoir s’est lancé dans le processus d’intégration de la technologie avancée. Un processus qui a abouti avec un protocole d’accord avec Cisco.

Création d’un centre de cybersécurité et Intelligence Artificielle au Maroc

L’Intelligence Artificielle se positionne peu à peu sur le continent africain. Et ce dans les universités de certains pays. En effet, l’Université Internationale du Maroc (UIR) se lance dans la danse afin d’être un centre stratégique de développement et d’innovation dans la région. Ainsi, l’université du Maroc a réussi à obtenir un protocole d’accord (MOU) avec Cisco. Un protocole d’accord qui s’inscrit dans le cadre de l’installation d’un Cisco EDGE Incubation Centre au sein de l’université pour le développement d’un centre de création en Intelligence Artificielle et cybersécurité.

Cette association entre les deux institutions pourrait avoir un impact positif sur le développement du pays et de la région. Cependant, pour que cet impact soit réel dans le nouveau partenariat de l’UIR, Cisco lance un appel aux institutions privées et publiques du pays. Ce dernier demande une promotion de cohésion entre l’université, le secteur privé et les institutions publiques. Une cohésion qui pourrait participer à l’accélération de l’innovation, d’impact durable dans le domaine de l’IA, dans le pays et sans oublier la région d’une part. Sur un autre plan, cette synergie permettra de faire entrer la nouvelle génération dans la formation de la technologie, faisant d’eux des leaders dans la technologie, notamment l’intelligence artificielle, par le biais du projet tels que la Cisco Networking Academy.

Avec la mise en œuvre de l’accord, soutiendra l’écosystème marocain de l’innovation, en pleine croissance. Soulignons que EDGE est un centre d’Experience, Design, Go-to-market, Earn. Ce dernier est en collaboration avec Cisco par le programme mondial Country Digital Acceleration de Cisco. Cette structure est le pilier de la transformation numérique en connectant le monde académique, les startups, les acteurs industriels et les institutions publiques, afin d’accélérer l’adoption des nouvelles technologies."

https://www.afrique-sur7.fr/intelligence-artificielle-le-maroc-proche-dun-exploit-historique

#metaglossia_mundus

#Metaglossia

The Cambridge Dictionary has added over 6,000 new words including slang terms like "skibidi," pronounced SKIH-bih-dee, "tradwife" and "delulu."

"“Skibidi,” pronounced SKIH-bih-dee, is one of the slang terms popularized by social media that are among more than 6,000 additions this year to the Cambridge Dictionary.

“Internet culture is changing the English language and the effect is fascinating to observe and capture in the dictionary,” said Colin McIntosh, lexical program manager at Cambridge Dictionary, the world’s largest online dictionary.

“Skibidi” is a gibberish term coined by the creator of an animated YouTube series and can mean “cool” or “bad” or be used with no real meaning as a joke.

Other planned additions include “tradwife," a contraction of “traditional wife” referring to a married mother who cooks, cleans and posts on social media, and "delulu,” a shortening of the word delusional that means “believing things that are not real or true, usually because you choose to.”

Christian Ilbury, senior lecturer in sociolinguistics at the University of Edinburgh, said many of the new words are tied to social media platforms like TikTok because that is how most young people communicate.

However, Ilbury said some of the words, including “delulu,” have longer histories than people might think and have been used by speech communities for years.

“It’s really just the increase in visibility and potential uptake amongst communities who may not have engaged with those words before,” he explained.

An increase in remote working since the pandemic has created the new dictionary entry “mouse jiggler,” a device or piece of software used to make it seem like you are working when you are not.

Environmental concerns are behind the addition of “forever chemical,” a harmful substance that remains in the environment for a long time.

Cambridge Dictionary uses the Cambridge English Corpus, a database of more than 2 billion words of written and spoken English, to monitor how new words are used by different people, how often and in what contexts they are used, the company said.

“If you look at what a dictionary’s function is, it’s a public record of how people use language and so if people are now using words like ‘skibidi’ or ‘delulu,’ then the dictionary should take account of that,” Ilbury said.

McIntosh added the dictionary has only added words it thinks have “staying power.”"

Cambridge Dictionary adds 'skibidi' and 'tradwife' among 6,000 new words

By The Associated Press

Updated August 18, 2025 5:15 pm

LONDON — What the skibidi is happening to the English language?

https://www.newsday.com/news/nation/cambridge-dictionary-new-additions-skibidi-tradwife-delulu-f58990

#metaglossia_mundus

#Metaglossia

"While States can often refer to a single language text of a multilingual treaty, there are times when an examination of other language texts is required. This article proposes a novel three-step method for applying Article 33(4) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties to remove, or otherwise reconcile, differences in meaning between multilingual treaty texts. In doing so, this article seeks to address the current vacuum of practical guidance on when an examination of different authentic treaty texts is necessary in the process of interpretation, and how any differences in meaning between the texts should be removed or reconciled."

Reconciling Divergent Meanings in the Interpretation of Multilingual Treaties

August 2025

International and Comparative Law Quarterly

74(2):467-484

DOI: 10.1017/S0020589325100778

License: CC BY 4.0

Cleo Hansen-Lohrey

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/394412373_Reconciling_Divergent_Meanings_in_the_Interpretation_of_Multilingual_Treaties

#Metaglossia

#metaglossia_mundus

"Classic of German Theatre translated into Welsh

10 Aug 2025

Georg Büchner’s Woyzeck from Melin Bapur Books

A masterpiece of German theatre has been published in a new Welsh edition.

At turns disturbing, tragic and moving, Georg Büchner’s Woyzeck is widely considered a masterpiece of European theatre, all the more remarkably so given that it remained unfinished after the death of the author aged just 23.

The play as it exists today is a reconstruction of scenes, some of which exist in mutliple versions, and whose original intended order is uncertain. Perhaps due to this very ambiguity it has been the subject of hundreds of productions and adaptations, including the opera Wozzeck by Alban Berg.

The play follows the tragic life of the eponymous Franz Woyzeck, a poor soldier struggling with poverty, exploitation, and mental instability.

To supplement his meagre income, he allows himself to be the subject of often bizarre medical experiments (such as eating nothing but peas) by a deranged doctor who treats him as less than human, as does his captain, both experiences worsening his physical and psychological condition.

Woyzeck’s mental deterioration intensifies as he becomes obsessed with the infidelity of his partner Marie, with whom he has a child. Driven by jealousy, despair, and a fractured sense of reality, he ultimately murders her. The play ends ambiguously, with Woyzeck’s fate uncertain.

Büchner’s unfinished, fragmented structure adds to the chaotic and disjointed atmosphere.

Welsh edition

The Welsh edition was translated by Sarah Pogoda, a lecturer in German at Bangor University, and Huw Jones. This team previously translated a Welsh learners’ version of Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis, but this new Welsh version of Woyzeck is for general Welsh audiences.

Translator Huw Jones explains: “The idea for the translation came from Sarah, who started learning Welsh on her third day here. She and many of her colleagues are so enthusiastic to contribute to Wales; it’s a real scandal that language departments are being closed in so many universities.

“Woyzeck has inspired so many different adaptations. And we soon found that we really had our work cut out puzzling over our own interpretation. Therefore, we were very lucky to have the expert eye and red biro of author Lloyd Jones (a Wales Book of the Year winner). Lloyd really pulled our draft translations together.

“The play has probably one of the earliest portrayals of the classic ‘mad professor’, who has since become such a Hollywood stock character. In the play, Woyzeck is made to eat a diet of only peas as a guinea pig in the unhinged doctor’s dubious experiments!

“But Woyzeck is far more than just a tale of betrayal and murder most foul. Like many classic works, the underlying themes — social class, gender roles, mental health, and human nature vs. the natural world — are as relevant today as when they were written.”

Relevance

His co-translator Sarah Pogoda added: “After alsmost 200 years, Woyzeck is still relevant for our lives today, I’d rather see us living in a world in which texts like Woyzeck would not speak to us anymore.”

The new Welsh edition is published by Melin Bapur books as part of their Clasuron Byd (World Classics) series, which aims to make important literary works from all over the world available in Welsh.

“We’re really excited to be able to bring this Welsh version of Woyzeck to readers, and perhaps some day a Welsh stage,” explains Melin Bapur editor, Adam Pearce.

“This is exactly the kind of work we wanted to make availabel in Welsh via our Clasuron Byd series. Interestingly, this isn’t the first Welsh version of Woyzeck – as I understand it a translation was made in the 1980s, but this is the first time the work has been published and made available to the reading public as a book.”

Woyzeck can be purchased from the Melin Bapur website, www.melinbapur.cymru for £7.99+P&P, as an eBook from a variety of eBook platforms, o from a range of bookshops across Wales and beyond."

https://nation.cymru/feature/classic-of-german-theatre-translated-into-welsh/

#metaglossia_mundus

#Metaglossia

"...The UAE has set a model in leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) to integrate the Arabic language and its cultural heritage into the digital sphere, boosting its regional and global presence as a language capable of meeting future demands.

Various state institutions are rolling out AI-driven initiatives in sectors such as publishing, education, lexicography and creative content.

One of the leading projects is the Historical Dictionary of Arabic Language, a monumental scientific achievement completed last year by Sharjah, the "Capital of Arab Culture". The project documents the evolution of the Arabic language throughout history.

This was followed by the launch of the “GPT Historical Dictionary of the Arabic Language” project, which utilises modern innovations to serve and disseminate the language globally. Linked to AI, the dictionary offers researchers and enthusiasts with over 20 million Arabic words. It also enables them to write and read texts, convert them into videos, and continuously feed the dictionary with new information through a collaboration between the Arabic Language Academy in Sharjah and the Emirates Scholar Research Centre.

Meanwhile, the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Knowledge Foundation is advancing digital culture and knowledge in the Arab world and globally through initiatives including the “Digital Knowledge Hub,” an Arabic platform for producing, collecting and organising digital content. Last year, it surpassed 800,000 titles and 8.5 million digital items across more than 18 specialised libraries.

The Abu Dhabi Arabic Language Centre, part of the Department of Culture and Tourism, has launched several AI-based publishing projects, including a specialised digital dictionary to support digital Arabic content. It is the first comprehensive Arabic-English dictionary employing AI and computational linguistics.

The dictionary covers over 7,000 core modern terms, offering automated pronunciation, simplified definitions, examples, images, and precise grammatical and semantic classifications.

In collaboration with a team from New York University Abu Dhabi and Zayed University, the centre launched the Balanced Arabic Readability Corpus project “BAREC”, which aims to collect a linguistic corpus of 10 million words encompassing a wide range of literary genres and topics.

The most recent edition of the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair saw the launch of the "Digital Square" initiative, a technical space that provided a platform to enhance the use of AI in publishing and books.

Furthermore, many educational institutions have been keen to launch diverse initiatives to promote the use of AI and modern technologies in teaching the Arabic language."

UAE harnesses AI to boost Arabic language global reach

Monday, August 11, 2025 1:05 PM

ABU DHABI, 10th August, 2025 (WAM)

https://www.wam.ae/en/article/15ppos9-uae-harnesses-boost-arabic-language-global-reach

#Metaglossia

#metaglossia_mundus

"Elle relativise l’arrivée de l’IA dans la traduction

Alors que l’IA prétend remplacer les traducteurs...

Clair Pickworth-Guinaudeau, est traductrice indépendante dans le Perche depuis vingt-cinq ans. |

Ouest-France

Publié le 19/08/2025 à 05h01

Trois questions à…

Clair Pickworth-Guinaudeau, traductrice

Comment devient-on traductrice ?

Je viens du Lincoln Shire, au nord de Londres. J’ai suivi une formation traditionnelle en Français et un peu de japonais. J’ai toujours voulu devenir traductrice mais une professeure m’a dit que je devais faire autre chose avant. Ma licence en poche, je suis partie pour six mois en France, d’où je ne suis jamais repartie. J’ai travaillé un temps dans l’enseignement professionnel mais j’avais toujours mon envie de traduction. J’ai donc fait un post graduate à l’Institute of linguistics de Londres et j’ai commencé à travailler de chez moi. Je me rappelle au début les lenteurs d’internet. Je devais attendre trois heures pour télécharger un fichier à traduire ! Pour les jeunes ça doit sembler aussi ringard que de communiquer avec des signaux de fumée… En fait, je suis en lien avec d’autres traducteurs sur des forums ou auprès d’un même client.

Avec l’intellingence artificielle (IA) le métier est-il en danger ?

Certes, les résultats sont impressionnants, il vaut mieux vérifier les textes produits. J’avais un a priori négatif sur l’IA alors dernièrement, j’ai suivi une formation à la Surrey University sur l’IA utilisée pour la traduction. Pour mieux combattre son ennemi, il faut le connaître ! J’utilisais déjà des outils informatisés telles que les mémoires de traduction pour une meilleure cohérence et une mise à jour des traductions successives. Ils gagnent du temps et fidélisent le client. Mais de là à être un métier d’avenir… Seulement en y associant de l’enseignement ou en se spécialisant dans un domaine. La traduction étant en bout de chaîne, les délais sont toujours plus courts. L’IA peut nous permettre de pré-traduire avant de vérifier que la formulation est correcte.

Quels sont vos projets futurs ?

Je vais essayer de varier mes prestations. Je voudrais être traductrice assermentée pour le tribunal car il paraît qu’ils en manquent. Je peux accompagner des personnes qui se préparent à un oral, que ce soit pour un examen ou un exposé professionnel. Mon fils Oliver a une entreprise de production vidéo, nous collaborerons peut-être pour des sous-titrages. Je peux aussi créer une version anglaise de sites internet de gîtes ou d’entreprises pour qu’ils s’ouvrent à d’autres publics. Et aider des Anglais qui veulent acheter ou s’installer en France avec les formalités administratives.

Clair Pickworth-Guinaudeau, partage aussi ses connaissances anglaises en organisant des tea time thématiques à la médiathèque."

https://www.ouest-france.fr/normandie/remalard-en-perche-61110/elle-relativise-larrivee-de-lia-dans-la-traduction-c24ba0c4-7b8d-11f0-86ed-565860524f67

#metaglossia_mundus

"French dictionary gets bad rap over Congolese banana leaf dish

Marthe BOSUANDOLE AFP Aug 14, 2025 Updated Aug 15, 2025

Diners flock to the terrace of Mother Antho Aembe's restaurant in downtown Kinshasa to enjoy "liboke", blissfully unaware of the linguistic brouhaha surrounding the Democratic Republic of Congo's national dish.

Made by grilling fish from the mighty River Congo wrapped in a banana-leaf parcel with spices, tomatoes, peppers, onions, garlic and chillies, liboke enjoys cult status across the central African country.

But liboke's inclusion in one of France's top dictionaries has upset Congolese intellectuals, who say its compilers have failed to capture the full meaning of a word derived from the local Lingala language and closely associated with national identity.

The Petit Larousse dictionary -- an encyclopaedic tome considered a foremost reference on the French language -- announced in May it was including liboke in its 2026 edition.

Its definition: "a dish made from fish or meat, wrapped in banana leaves and cooked over charcoal."

Tucking into a plate on the terrace in the city centre, civil servant Patrick Bewa said it was a "source of pride" that liboke had made it into the leading French dictionary.

"We love it, it's really a typically African and Congolese meal," he said. "With the smoky flavour which takes on the aroma of the leaf, it's an inimitable taste. You have to taste it to believe it."

But some scholars argue that the definition was compiled in Paris by the Academie francaise (French Academy), the chief arbiter on matters pertaining to the French language, without doing justice to liboke's original meanings.

- 'United and undivided' -

Referring only to liboke as food is "very reductive", argued Moise Edimo Lumbidi, a cultural promoter and teacher of Lingala, one of scores of languages spoken in the DRC where French remains the official language.

Under dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, whose rise to power was helped by former colonial master Belgium and whose kleptocratic rule was backed by the United States as a bulwark against Cold War communism, liboke was even part of the national slogan.

"Tolingi Zaire liboke moko, lisanga moko," was a rallying cry, meaning: "We want a united and undivided Zaire", the former name for the DRC during Mobutu's 32 years in power.

"I'm not happy about restricting this precious word, so essential to our culture... liboke moko, it's above all that communion, that national unity," writer and former international cooperation minister Pepin Guillaume Manjolo told AFP.

"Limiting it to its culinary aspects may be all very well for the French, but for us it will not do."

The Petit Larousse should have drawn up the definition by consulting the literary academies of the DRC and its neighbour the Republic of Congo, as the region where the word originated, he said.

AFP contacted the publishers of the Petit Larousse dictionary for comment but did not receive an immediate response.

Edimo, the language teacher, explained that in Lingala, liboke means "a little group".

While liboke's inclusion in the dictionary is a good thing, Edimo said, Larousse's compilers should "deepen their research so as to give us the true etymology of the word".

That would be "a way for them to express their respect for our culture", he added.

At her restaurant in Kinshasa's upscale Gombe district, 41-year-old Mother Aembe was unaware of liboke's newfound literary status, but said she just hoped it would bring in more customers.

mbb/sbk/kjm"

https://www.lebanondemocrat.com/maconcounty/news/national/french-dictionary-gets-bad-rap-over-congolese-banana-leaf-dish/article_44460802-4e64-556b-8ce3-924131888f04.html

#Metaglossia

#metaglossia_mundus

DSPS Specialist/ASL Interpreter

Ventura County Community College DistrictSalary: $82,344.00 - $113,712.00 Annually Job Type: Classified Job Number: 2025-00672 Location: Oxnard College (Oxnard CA), CA Department: Districtwide Closing: 9/25/2025 11:59 PM Pacific Description

WHAT YOU'LL DOUnder the general supervision of an assigned supervisor, a DSPS (Disabled Students Programs and Services)/ASL Interpreter performs a variety of specialized duties involved in the planning, scheduling, and providing of services for students with disabilities; coordinates and implements communication support services for students who are deaf or hard of hearing; serves as an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter. There is currently one full-time (40 hours/week, 12 months/year) vacancy located at Oxnard College.This recruitment is being conducted to establish a list of eligible candidates that will be used to fill district-wide, current and upcoming, non-bilingual and bilingual, temporary and regular vacancies for the duration of the list, not to exceed one year. WHERE YOU'LL WORKOxnard College was founded in 1975 and is the newest of the three community colleges in the county. Set on 118 acres and located two miles from Pacific Ocean beaches, the college is easily accessible by the Ventura Freeway (Highway 101) or the Pacific Coast Highway.

More information about Oxnard College can be found here: Oxnard College.

WHO WE AREThe Ventura County Community College District (VCCCD) is a public community college district serving residents throughout Ventura County. VCCCD's three colleges - Moorpark College, Oxnard College, and Ventura College - offer programs for transfer to four-year colleges and universities; career technical training, basic skills instruction; as well as community service, economic development, and continuing education for cultural growth, life enrichment, and skills improvement. The Ventura County Community College District recognizes that a diverse community of faculty, staff, and administrators promotes academic excellence and creates an inclusive educational and work environment for its employees, contractors, students, and the community it serves. With the understanding that a diverse community fosters multicultural awareness, promotes mutual understanding and respect, and provides role models for all students, VCCCD is committed to recruiting and employing a diverse and qualified group of administrators, faculty, and staff members who are dedicated to the success of all college students. The Ventura County Community College District does not engage in any employment practice that discriminates against any employee or applicant for employment on the basis of ethnic group identification, race, color, language, accent, immigration status, ancestry, national origin, political beliefs, age, gender, sex, religion, transgender, sexual orientation, marital status, veteran status, and/or physical or mental disability. SALARY PLACEMENT

New Employees: Generally, new employees are placed on the first step of the appropriate range of the salary schedule. Current Employees: An employee who is promoted will be placed on the salary step of the new range of the appropriate salary schedule that provides a minimum increase comparable to a one-step increase in salary. New and current employees may be eligible for advanced step placement as outlined in Section 290 - SALARY PLAN in the Rules of the Personnel Commission for Classified Employees (Download PDF reader).Representative Duties

Serve as a technical resource and provide information and assistance to counselors, and other program faculty and staff regarding the needs and characteristics of individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing, and Deaf culture. EAssess communication styles and ASL language acquirement for students who are deaf or hard of hearing; assign hourly staff compatible with the communication styles of the students; respond to and resolve issues related to hourly staff assignments. ECollaborate with counselors and other program faculty on the development of individual student accommodation plans for students who are deaf or hard of hearing. EInterpret using ASL in classrooms, labs, tutoring sessions, and counseling appointments for students who are deaf or hard of hearing. EAssist counselors and other program faculty with outreach, orientation, and specialized registration assistance for students with disabilities. EProvide information, training, and assistance regarding resources, equipment, supplies, and services available to students who are deaf or hard of hearing; instruct students in the proper operation of specialized software and equipment; arrange for equipment loans. ERecruit, hire, train, provide work direction to, and evaluate hourly sign language interpreters, captioning providers, readers, tutors, scribes, and note takers; maintain work schedules and identify substitutes, as necessary. EProvide input and assistance to program faculty, counselors, and administrators regarding the development and implementation of specialized support services, programs, activities, and projects for students with disabilities. EEnter, retrieve, compile, and organize student data and prepare various reports related to program activities in accordance with State and federal regulations. EMonitor and track hourly staff and captioning services expenses; maintain current budget information. EWork collaboratively and professionally with faculty, staff, students, and stakeholders from diverse academic, socioeconomic, cultural, disability, gender identity, and ethnic communities. EDemonstrate cultural humility, sensitivity, and equity-mindedness in working with individuals from diverse communities; model inclusive behaviors; and achieve equity in assignment-related outcomes. EPerform other duties as assigned. E = Essential Duties Minimum Qualifications

Graduation from high school or evidence of equivalent educational proficiency AND five years of American Sign Language interpreting experience. OR An associate degree from a recognized college or university AND four years of American Sign Language interpreting experience. OR A Bachelor's degree from a recognized college or university AND three years of American Sign Language interpreting experience. LICENSES AND OTHER REQUIREMENTS: Certification from Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf or National Association of the Deaf (Interpreter Level 3 or above) within six months of hire. Supplemental Information

EXAMINATION AND SELECTION PROCESS This is an examination open to the public and current District employees seeking a promotional opportunity. To ensure consideration, please submit your application materials by the posted deadline date on this bulletin. The examination process may consist of any of the following components: A) American Sign Language Skill Evaluation = Qualifying (pass/fail) B) Technical Interview = 100% weighting on final score The candidates with the highest passing scores on the American Sign Language skill evaluation will be invited to the technical interview. The examination process is subject to change as needs dictate. All communication regarding this process will be delivered via email.AMERICAN SIGN LANGUAGE SKILLS EVALUATIONDate Range: Friday, October 3, 2025 to Thursday, October 9, 2025TECHNICAL INTERVIEW

Date Range: Friday, October 17, 2025 to Thursday, October 23, 2025 PLEASE NOTE: The American Sign Language Skill Evaluation will be conducted in person at the District Administrative Center located in Camarillo. The Technical Interviews will be conducted remotely via Zoom.The examination components and dates are subject to change as needs dictate. All communication regarding this process will be delivered via email. SUBMISSION OF APPLICATION Applicants must meet the minimum qualifications as stated, including the possession of licenses, certifications, or other requirements, by the filing deadline in order to move forward in the recruitment process. You must attach copies of any documents that demonstrate your attainment of the minimum qualifications (e.g., unofficial transcripts, foreign transcript evaluation, copies of any required licenses, and/or certifications). Failure to submit any required documents may result in disqualification. All required documentation must be attached to your application; Human Resources staff will not upload your documents for you. The VCCCD does not accept letters of recommendation for classified positions. Please do not attempt to attach letters of recommendation to your application. PLEASE BE AWARE THAT ONCE YOU HAVE SUBMITTED YOUR APPLICATION YOU WILL NO LONGER BE ABLE TO MAKE REVISIONS. If additional versions of your application are submitted, only the most recent will be considered. When completing the application, please make sure you include ALL current and previous employment in the Work Experience section of the application and complete ALL fields, including the name and contact information for your supervisors. Duration of work experience is calculated based off a standard 40-hour full-time work week. Part-time work experience will be prorated based on a 40-hour full-time work week. Experience that is included in the resume but not in the Work Experience section of the application may not be considered for the purpose of determining whether you meet the minimum qualifications. When completing the supplemental questionnaire (if applicable), outline in detail your education, training (such as classes, seminars, workshops), and experience. ELIGIBILITY LIST Upon completion of the examination, the eligibility list will be compiled by combining the final examination score with applicable seniority and veteran's credits, if any. The candidates will be ranked according to their total score on the eligibility list. Certification will be made from the highest three ranks of the eligibility list. This eligibility list will be used to fill current vacancies for up to one year from the date of the technical interview. PROBATIONARY PERIOD All appointments made from eligibility lists for initial appointment or for promotion, with certain exceptions, shall be probationary for a period of six (6) months or one hundred thirty (130) days of paid service, whichever is longer. Classified management, police, and designated executive classifications shall be probationary for a period of one (1) year of paid service from initial appointment or promotion. ACCOMMODATIONS Individuals with disabilities requiring reasonable accommodation in the selection process must inform the Ventura County Community College District Human Resources Department in writing no later than the filing date stated on the announcement. Those applicants needing such accommodation should document this request in an email to HRMail@vcccd.edu including an explanation as to the type and extent of accommodation needed to participate in the selection process. DEGREE INFORMATION If a degree/coursework is used to meet minimum qualifications, an official copy of your transcripts will be required upon hire. If you have a foreign degree and the institution from which your degree was granted is not recognized as accredited by the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA) or the U.S. Department of Education, foreign transcript evaluation is required if the foreign degree/coursework is used to meet minimum qualifications. The foreign transcript evaluation must be included with your application materials. Visit the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA) or the U.S. Department of Education to search for institutions that are recognized as accredited. If you need your transcripts evaluated, please review the list of agencies approved for foreign transcript evaluation (Download PDF reader) (Download PDF reader). If applicable, an official copy of your foreign transcript evaluation will also be required upon hire. For more information about the recruitment process at VCCCD, including responses to Frequently Asked Questions, please visit our Classified Careers page. To apply, please visit https://www.schooljobs.com/careers/vcccd/jobs/5036075/dsps-specialist-asl-interpreterjeid-d34de02fe3f87d45b0870de0cbb3b1e2 Send job SavejobClick to add the job to your shortlist

"Abstract: This paper presents the first comprehensive deep learning-based Neural Machine Translation (NMT) framework for the Kashmiri-English language pair. We introduce a high-quality parallel corpus of 270,000 sentence pairs and evaluate three NMT architectures: a basic encoder-decoder model, an attention-enhanced model, and a Transformer-based model. All models are trained from scratch using byte-pair encoded vocabularies and evaluated using BLEU, GLEU, ROUGE, and ChrF + + metrics. The Transformer architecture outperforms RNN-based baselines, achieving a BLEU-4 score of 0.2965 and demonstrating superior handling of long-range dependencies and Kashmiri’s morphological complexity. We further provide a structured linguistic error analysis and validate the significance of performance differences through bootstrap resampling. This work establishes the first NMT benchmark for Kashmiri-English translation and contributes a reusable dataset, baseline models, and evaluation methodology for future research in low-resource neural translation."

Published: 16 August 2025

Deep neural architectures for Kashmiri-English machine translation

Syed Matla Ul Qumar, Muzaffar Azim, …Yonis Gulzar

Scientific Reports volume 15, Article number: 30014 (2025)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-14177-8

#Metaglossia

#metaglossia_mundus

"Abstract: Pre-trained models have become widely adopted for their strong zero-shot performance, often minimizing the need for task-specific data. However, specialized domains like medical speech recognition still benefit from tailored datasets. We present ADMEDVOICE, a novel Polish medical speech dataset, collected using a high-quality text corpus and diverse recording conditions to reflect real-world scenarios. The dataset includes domain-specific vocabulary such as drug names and illnesses, with nearly 15 hours of audio from 28 speakers, including noisy environments. Additionally, we release two enhanced versions: one anonymized for privacy-sensitive use and another synthetic version created via text-to-speech, totaling over 83 hours and nearly 50,000 samples. Evaluating the Whisper model, we observe a 24.03 WER on our test set. Fine-tuning with human recordings reduces WER to 15.47, and incorporating anonymized and synthetic data further lowers it to 13.91. We open-source the dataset, fine-tuned model, and code on Kaggle to support continued research in medical speech recognition."

Published: 16 August 2025

A Comprehensive Polish Medical Speech Dataset for Enhancing Automatic Medical Dictation

Andrzej Czyżewski, Sebastian Cygert, …Krzysztof Narkiewicz

Scientific Data volume 12, Article number: 1436 (2025)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-025-05776-1

#metaglossia_mundus

#Metaglossia

"Now We’re Talking: NVIDIA Releases Open Dataset, Models for Multilingual Speech AI

The new Granary dataset, featuring around 1 million hours of audio, was used to train high-accuracy and high-throughput AI models for audio transcription and translation.

Of around 7,000 languages in the world, a tiny fraction are supported by AI language models. NVIDIA is tackling the problem with a new dataset and models that support the development of high-quality speech recognition and translation AI for 25 European languages — including languages with limited available data like Croatian, Estonian and Maltese.

These tools will enable developers to more easily scale AI applications to support global users with fast, accurate speech technology for production-scale use cases such as multilingual chatbots, customer service voice agents and near-real-time translation services. They include:

Granary, a massive, open-source corpus of multilingual speech datasets that contains around a million hours of audio, including nearly 650,000 hours for speech recognition and over 350,000 hours for speech translation.

NVIDIA Canary-1b-v2, a billion-parameter model trained on Granary for high-quality transcription of European languages, plus translation between English and two dozen supported languages. It tops Hugging Face’s leaderboard of open models for multilingual speech recognition accuracy.

NVIDIA Parakeet-tdt-0.6b-v3, a streamlined, 600-million-parameter model designed for real-time or large-volume transcription of Granary’s supported languages. It has the highest throughput of multilingual models on the Hugging Face leaderboard, measured as duration of audio transcribed divided by computation time.

The paper behind Granary will be presented at Interspeech, a language processing conference taking place in the Netherlands, Aug. 17-21. The dataset, as well as the new Canary and Parakeet models, are now available on Hugging Face.

How Granary Addresses Data Scarcity

To develop the Granary dataset, the NVIDIA speech AI team collaborated with researchers from Carnegie Mellon University and Fondazione Bruno Kessler. The team passed unlabeled audio through an innovative processing pipeline powered by NVIDIA NeMo Speech Data Processor toolkit that turned it into structured, high-quality data.

This pipeline allowed the researchers to enhance public speech data into a usable format for AI training, without the need for resource-intensive human annotation. It’s available in open source on GitHub.

With Granary’s clean, ready-to-use data, developers can get a head start building models that tackle transcription and translation tasks in nearly all of the European Union’s 24 official languages, plus Russian and Ukrainian.

For European languages underrepresented in human-annotated datasets, Granary provides a critical resource to develop more inclusive speech technologies that better reflect the linguistic diversity of the continent — all while using less training data.

The team demonstrated in their Interspeech paper that, compared to other popular datasets, it takes around half as much Granary training data to achieve a target accuracy level for automatic speech recognition (ASR) and automatic speech translation (AST).

Tapping NVIDIA NeMo to Turbocharge Transcription

The new Canary and Parakeet models offer examples of the kinds of models developers can build with Granary, customized to their target applications. Canary-1b-v2 is optimized for accuracy on complex tasks, while parakeet-tdt-0.6b-v3 is designed for high-speed, low-latency tasks.

By sharing the methodology behind the Granary dataset and these two models, NVIDIA is enabling the global speech AI developer community to adapt this data processing workflow to other ASR or AST models or additional languages, accelerating speech AI innovation.

Canary-1b-v2, available under a permissive license, expands the Canary family’s supported languages from four to 25. It offers transcription and translation quality comparable to models 3x larger while running inference up to 10x faster.

NVIDIA NeMo, a modular software suite for managing the AI agent lifecycle, accelerated speech AI model development. NeMo Curator, part of the software suite, enabled the team to filter out synthetic examples from the source data so that only high-quality samples were used for model training. The team also harnessed the NeMo Speech Data Processor toolkit for tasks like aligning transcripts with audio files and converting data into the required formats.

Parakeet-tdt-0.6b-v3 prioritizes high throughput and is capable of transcribing 24-minute audio segments in a single inference pass. The model automatically detects the input audio language and transcribes without additional prompting steps.

Both Canary and Parakeet models provide accurate punctuation, capitalization and word-level timestamps in their outputs."

August 15, 2025 by Jonathan Cohen

https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/speech-ai-dataset-models/

#Metaglossia

"...Some terms commonly used to describe peoples’ interactions with wildlife like “human-wildlife conflict,” “crop-raiding” and “pest” are detrimental to the understanding of animals and their conservation.

“There’s no denying that there will be situations when human and wildlife interests collide, but we can take a step back, consider the power differential between ourselves and other animals, and take a more sympathetic view of these problems,” the author argues.

Language shapes the way we view our world. In the field of wildlife conservation, even very subtle word choices drive peoples’ perceptions around individual species or situations. These word choices can be illustrated by the language associated with wildlife value orientations (WVO).

When asked about views toward wildlife, individuals often fall into one of two camps: domination or mutualism. Those with a domination perspective tend to view wildlife as a resource to be controlled and used according to human needs. People with a mutualism ideology see wildlife as an extended part of our community, and therefore deserving of our respect and protection. Words like “management” or “resources” are associated with a domination perspective, while those with a mutualism orientation are more likely to view wildlife in human terms, or focus on animal welfare.

Wildlife value orientations are influenced by many social and economic factors, and they are not static. Attitudes in both the U.S. and the U.K. have moved from domination to more mutualism orientations, and this change is strongest in younger and more educated groups. As attitudes toward wildlife shift over time, the language we use to describe other animals will naturally change. Conservationists can actively encourage shifting perspectives toward more positive interactions with wildlife by choosing their language carefully. Some terms that should be replaced are “human-wildlife conflict,” “crop-raiding” and “pest,” because this language depicts humans and nonhumans as enemies.

The IUCN defines human-wildlife conflict as “when animals pose a direct and recurring threat to the livelihood or safety of people.” This could mean competition for resources such as food or space, the economic impact of lost crops or livestock, infectious disease transmission, or close proximity to large and physically dangerous wildlife. These issues have been with us for the history of our species, but as the human population continues to grow and require more land, further restricting wild spaces, these issues are becoming more common and more extreme.

It is easy to understand why people would be concerned with these issues. Animals can pose very real threats to peoples’ health, safety and economic stability. However, many scholars have noted that the language of human-wildlife conflict portrays wildlife as if they are actively, purposefully opposed to human interests. One study reviewed scientific papers using that phrase and found that only one of more than 400 studies actually described a conflict situation, in which both actors demonstrate opposing goals or values. This is because wild animals are unaware of human interests and therefore cannot actively work against them. Essentially, the word “conflict” attributes human motivations to nonhuman beings.

“Human-animal conflict” is just one example of wildlife rhetoric evoking crime, war and xenophobia. “Invasive,” “alien” and “foreign” are used to describe animals found outside their expected range. While “invasive” does have an ecological meaning — referring to a species with rapid spread and a detrimental impact on an ecosystem — this is not automatically a result of a species being introduced to a new environment.

Regardless, the animals have not intentionally chosen to invade foreign territory; they are simply trying to survive in a new landscape. One study on urban coyotes describes the importance of language for human-animal relations, finding that depicting coyotes as “invaders” or “foreign” fostered negative opinions of the animals and increased peoples’ fear for their own (and their pets’) safety, despite the fact that the coyotes were residing within their traditional home range...

Tracie McKinney

14 Aug 2025

https://news.mongabay.com/2025/08/its-time-to-update-the-language-of-human-wildlife-interactions-commentary/

#Metaglossia

"Edinburgh University Press has issued directives requiring writers to use capital letters for "Black" while keeping "white" in lowercase when discussing racial matters.

The academic publisher attributes this distinction to what it terms "political connotations".

The publishing house's new guidelines assert that "Black" merits capitalisation as it denotes "a distinct cultural group and a shared sense of identity and community".

Conversely, the instructions explicitly state: "Please do not capitalise 'white' due to associated political connotations".

These requirements appear in the publisher's comprehensive guide on inclusive terminology, which itself carries advisories about "potentially triggering" content.

The publisher's language guidance extends beyond racial terminology to numerous other areas.

Writers must avoid describing migrants as "illegal" and should replace "homeless" with "unhoused" according to the new rules.

Economic terminology faces similar restrictions.

The guide instructs authors to eschew the word "poor" in favour of phrases such as "under-represented", "currently dealing with food insecurity" or "economically exploited".

These stipulations form part of Edinburgh University Press's broader inclusive language framework, which the institution has developed for its annual output of approximately 300 publications...

The guidelines impose restrictions on geographical terminology, forbidding authors from employing broad classifications such as "Eastern" and "Western". Gender-related language faces extensive revision under the new framework.

Writers must eschew terms suggesting binary gender distinctions, including "opposite sex".

The publisher mandates using individuals' chosen pronouns or defaulting to "they" when uncertain. Traditional gendered nouns like "postman" and "chairman" are prohibited.

The guidance concludes with requirements for content warnings...

These mandatory alerts must cover violence, animal cruelty, substance use, transphobia and classism amongst other topics deemed potentially distressing to readers...

These linguistic modifications reflect broader institutional transformations that gained momentum following the 2020 Black Lives Matter demonstrations. Educational establishments have embraced initiatives to confront what they term "embedded whiteness" in professional environments.

The Telegraph disclosed that London Museum personnel received guidance on challenging "whiteness" in their workplace. Teacher training programmes have incorporated modules on disrupting "the centrality of whiteness" within educational settings.

Healthcare institutions have similarly revised their terminology. Various NHS trusts substituted "mother" with expressions like "birthing person" and "people who have ovaries".

Certain services proposed that "chestfeeding" by transgender individuals equates to maternal breastfeeding."

https://www.gbnews.com/news/woke-madness-language-guidance-black-white-ethnicity

#metaglossia_mundus

"Explore how high-quality data and semantic interoperability power the CMS Interoperability Framework and innovation in the health tech ecosystem.

Healthcare technology is set to undergo a monumental transformation, moving from a focus on EHR functionality to a focus on API exchange. At the heart of this evolution lies interoperability, the ability to seamlessly share and use data across different systems. The CMS Interoperability Framework could be emerging as a pivotal force driving this change. But there are other forces at play. By emphasizing shared standards and collaboration among patients, providers, payers, and digital health technologies, these forces are poised to evolve the health tech ecosystem.

Yet, even as some healthcare organizations adopt robust data exchange pathways, the ultimate goal, the last mile as it were, semantic interoperability, remains out of reach for many. While data exchange has improved, the next challenge is making that data complete, meaningful, and actionable...

Understanding the CMS Interoperability Framework

The CMS Interoperability Framework serves as a voluntary roadmap for organizations committed to advancing healthcare data exchange. This framework prioritizes a patient-centered approach and encourages participation from all healthcare stakeholders. By focusing on standardization and enabling technologies, CMS aims to foster seamless collaboration across the health tech ecosystem. Early adopters span the healthcare ecosystem with promises to share data and build patient-facing apps in three topical areas...

...

Operational efficiency