Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Charles Tiayon

November 23, 2022 11:19 PM

|

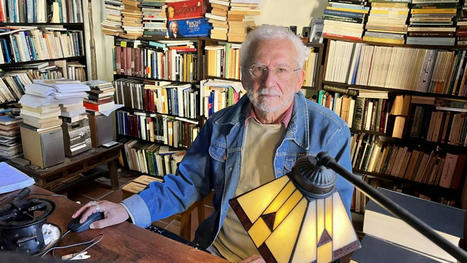

“El planeta Mercurio me ha condenado a traducir libros” Tengo 76 años. Nací en Madrid (bajo el signo de Cáncer) y vivo en la isla de Eivissa desde 1974. Soy traductor. Casado con Jackie, tenemos dos hijos, Amable (47) y Hermán (45), y nietos. ¿ Política? ¿Creencias? Belleza, naturaleza, libros y astrología. La lengua española está siendo desfigurada Carlos Manzano,traductor El mejor ‘Ulises’ de Joyce He conocido a un mago de las palabras y los astros. Aislado en la cima de una verde colina de Eivissa, traduce libros. Carlos Manzano suma seis premios de traducción en tres idiomas –ingles, francés, italiano– y su precioso trabajo enriquece la cultura de España. Su obra como traductor es un capital cultural de primera magnitud que merece gratitud de los lectores en español. Ha traducido a Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Henry Miller, Marcel Proust, James Joyce, está con Sterne ( Tristam Shandy ), Anaïs Nin, Virginia Woolf, Pessoa... “Huí del mundo”, me resume, por no someterse a lo peor de España, como Joyce huyó de Irlanda: “¡La huida es la victoria!”. Aparece su Ulises (Navona), del que me dice: “Al fin una traducción que, como el original, es una obra de arte del lenguaje”. Vive usted en un paraíso... Puig d’Atzaró, Eivissa, en mi casa payesa entre bosques. ¡Y entre libros! El planeta Mercurio me ha condenado a la comunicación lingüística, a traducir libros. Podría escribirlos. ¿Para qué? Ya se escriben miles de libros, pero hay muy pocas buenas traducciones. ¿Qué es un traductor? Un artista. ... De una obra de arte hace otra obra de arte. ¿Qué es lo último que ha traducido? Todo Proust, del francés al español. ¡Todo Proust! Y todo Joyce, del inglés al español. ¡Todo Joyce! Sale ahora mi Ulises, puede leerlo. Nadie ha escrito en lengua inglesa como Joyce. ¡Cuánto placer! He disfrutado mucho. ¿Le ha costado mucho traducirlo? Han sido 464 días seguidos: tres páginas al día, revisadas con Jackie, mi esposa. ¿Qué encontraré si leo su Ulises ? Arte. Libro duro y trágico, el capítulo XV es humorístico: ¡cuánto me he divertido! De jovencito leí Ulises en la traducción de Valverde. Mala: Valverde no sabía traducir. Ser catedrático no te hace traductor. Y usted ha hecho arte, me dice. Si Joyce hubiese escrito en español, su Ulises sería el mío, nunca el de Valverde. ¿Y Proust, qué diría de su traducción? Que si hubiese escrito en español, su obra sería exactamente como mi traducción. Parece que haya hablado con ellos... Les tengo muy bien estudiados. Como yo mismo, Proust había nacido bajo el signo de Cáncer, algo difícil para un hombre. Me insiste usted en los astros... Desde hace decenios verifico que la carta astral de cada persona explicita sus dones, pasiones y nudos. ¡Y nunca me ha fallado! ¿Y qué explicitan los astros de Proust? Que necesitaba besos de mamá. Criado muy enmadrado y rico, fue niño hasta que pasó a anciano: nunca fue hombre adulto. ¿Y Joyce? Era Acuario: la amistad es lo más valioso con una mujer. Y formó una pareja sexual abierta, muy valiente para entonces. ¿Y para usted? Jackie es Capricornio, ¡el mejor signo para una mujer! Debido a la serenidad de esta mujer llevamos cincuenta años juntos. ¿No es usted sereno? Soy colérico, autoexigente y exigente. Deme un ejemplo de eso. Cada mañana leo la prensa y hago inventario de sus muchos errores lingüísticos, calcos aberrantes del inglés: ¡es monstruosa la actual desfiguración del español! Ya veo que eso le preocupa... España desprecia al corrector, por eso se les contrata inexpertos y baratos... Y añaden más errores de los que reparan. Le gusta hacer amigos, veo también. Exceptúo a la editorial Navona, cuyos correctores me han hecho atinadas aportaciones. ¡Por primera vez en mi vida! ¿Cómo llegaron las letras a su vida? A mis cuatro años, mi padre tomó una pizarra y dijo: “Y ahora vamos a aprender a leer”. Qué momento, aún estoy viéndolo. ¿Aprendió rápido? Leía todos los carteles en el metro y la gente se admiraba: “¡Qué niño, qué niño!”. Mi padre murió a mis ocho años... Y usted siguió con las letras... Estudié febrilmente gramática. Becado, acabé Letras en Barcelona, me dio clases Gabriel Ferrater y obtuve matrícula de honor en Lengua y Literatura Catalana. Útil para Eivissa. Desde 1974 vivo aquí con Jackie. Tengo al ibicenco por la variante más bella de todo el dominio lingüístico catalán. ¿Por qué eligió Eivissa? ¡Es el cielo en la tierra! Nos vinimos a vivir sin luz eléctrica, con agua de pozo... Fui antifranquista y al fin me alejé del espanto del comunismo, tuve curiosidad por el hippismo. Y traducía, traducía... ¿Qué lenguas traduce? Castellano, catalán, italiano, portugués, gallego, francés, inglés... ¿Con alguna preferencia? La lengua más hermosa que existe es el gallego. ¿Sí? Lea Le petit prince en gallego y descubrirá que ¡es más bonito que en francés! ¿Y en español? Mi palabra en español favorita proviene delcaló, al igual que el verbo pirarse . Irse. Sí. Mi palabra es piravar, y sus variantes apiravar, piravelar y apiravelar. No conocía esas palabras. Todo se pierde, es una pena. ¿Y qué significa piravar? Follar. Por lo de irse.

Researchers across Africa, Asia and the Middle East are building their own language models designed for local tongues, cultural nuance and digital independence

"In a high-stakes artificial intelligence race between the United States and China, an equally transformative movement is taking shape elsewhere. From Cape Town to Bangalore, from Cairo to Riyadh, researchers, engineers and public institutions are building homegrown AI systems, models that speak not just in local languages, but with regional insight and cultural depth.

The dominant narrative in AI, particularly since the early 2020s, has focused on a handful of US-based companies like OpenAI with GPT, Google with Gemini, Meta’s LLaMa, Anthropic’s Claude. They vie to build ever larger and more capable models. Earlier in 2025, China’s DeepSeek, a Hangzhou-based startup, added a new twist by releasing large language models (LLMs) that rival their American counterparts, with a smaller computational demand. But increasingly, researchers across the Global South are challenging the notion that technological leadership in AI is the exclusive domain of these two superpowers.

Instead, scientists and institutions in countries like India, South Africa, Egypt and Saudi Arabia are rethinking the very premise of generative AI. Their focus is not on scaling up, but on scaling right, building models that work for local users, in their languages, and within their social and economic realities.

“How do we make sure that the entire planet benefits from AI?” asks Benjamin Rosman, a professor at the University of the Witwatersrand and a lead developer of InkubaLM, a generative model trained on five African languages. “I want more and more voices to be in the conversation”.

Beyond English, beyond Silicon Valley

Large language models work by training on massive troves of online text. While the latest versions of GPT, Gemini or LLaMa boast multilingual capabilities, the overwhelming presence of English-language material and Western cultural contexts in these datasets skews their outputs. For speakers of Hindi, Arabic, Swahili, Xhosa and countless other languages, that means AI systems may not only stumble over grammar and syntax, they can also miss the point entirely.

“In Indian languages, large models trained on English data just don’t perform well,” says Janki Nawale, a linguist at AI4Bharat, a lab at the Indian Institute of Technology Madras. “There are cultural nuances, dialectal variations, and even non-standard scripts that make translation and understanding difficult.” Nawale’s team builds supervised datasets and evaluation benchmarks for what specialists call “low resource” languages, those that lack robust digital corpora for machine learning.

It’s not just a question of grammar or vocabulary. “The meaning often lies in the implication,” says Vukosi Marivate, a professor of computer science at the University of Pretoria, in South Africa. “In isiXhosa, the words are one thing but what’s being implied is what really matters.” Marivate co-leads Masakhane NLP, a pan-African collective of AI researchers that recently developed AFROBENCH, a rigorous benchmark for evaluating how well large language models perform on 64 African languages across 15 tasks. The results, published in a preprint in March, revealed major gaps in performance between English and nearly all African languages, especially with open-source models.

Similar concerns arise in the Arabic-speaking world. “If English dominates the training process, the answers will be filtered through a Western lens rather than an Arab one,” says Mekki Habib, a robotics professor at the American University in Cairo. A 2024 preprint from the Tunisian AI firm Clusterlab finds that many multilingual models fail to capture Arabic’s syntactic complexity or cultural frames of reference, particularly in dialect-rich contexts.

Governments step in

For many countries in the Global South, the stakes are geopolitical as well as linguistic. Dependence on Western or Chinese AI infrastructure could mean diminished sovereignty over information, technology, and even national narratives. In response, governments are pouring resources into creating their own models.

Saudi Arabia’s national AI authority, SDAIA, has built ‘ALLaM,’ an Arabic-first model based on Meta’s LLaMa-2, enriched with more than 540 billion Arabic tokens. The United Arab Emirates has backed several initiatives, including ‘Jais,’ an open-source Arabic-English model built by MBZUAI in collaboration with US chipmaker Cerebras Systems and the Abu Dhabi firm Inception. Another UAE-backed project, Noor, focuses on educational and Islamic applications.

In Qatar, researchers at Hamad Bin Khalifa University, and the Qatar Computing Research Institute, have developed the Fanar platform and its LLMs Fanar Star and Fanar Prime. Trained on a trillion tokens of Arabic, English, and code, Fanar’s tokenization approach is specifically engineered to reflect Arabic’s rich morphology and syntax.

India has emerged as a major hub for AI localization. In 2024, the government launched BharatGen, a public-private initiative funded with 235 crore (€26 million) initiative aimed at building foundation models attuned to India’s vast linguistic and cultural diversity. The project is led by the Indian Institute of Technology in Bombay and also involves its sister organizations in Hyderabad, Mandi, Kanpur, Indore, and Madras. The programme’s first product, e-vikrAI, can generate product descriptions and pricing suggestions from images in various Indic languages. Startups like Ola-backed Krutrim and CoRover’s BharatGPT have jumped in, while Google’s Indian lab unveiled MuRIL, a language model trained exclusively on Indian languages. The Indian governments’ AI Mission has received more than180 proposals from local researchers and startups to build national-scale AI infrastructure and large language models, and the Bengaluru-based company, AI Sarvam, has been selected to build India’s first ‘sovereign’ LLM, expected to be fluent in various Indian languages.

In Africa, much of the energy comes from the ground up. Masakhane NLP and Deep Learning Indaba, a pan-African academic movement, have created a decentralized research culture across the continent. One notable offshoot, Johannesburg-based Lelapa AI, launched InkubaLM in September 2024. It’s a ‘small language model’ (SLM) focused on five African languages with broad reach: Swahili, Hausa, Yoruba, isiZulu and isiXhosa.

“With only 0.4 billion parameters, it performs comparably to much larger models,” says Rosman. The model’s compact size and efficiency are designed to meet Africa’s infrastructure constraints while serving real-world applications. Another African model is UlizaLlama, a 7-billion parameter model developed by the Kenyan foundation Jacaranda Health, to support new and expectant mothers with AI-driven support in Swahili, Hausa, Yoruba, Xhosa, and Zulu.

India’s research scene is similarly vibrant. The AI4Bharat laboratory at IIT Madras has just released IndicTrans2, that supports translation across all 22 scheduled Indian languages. Sarvam AI, another startup, released its first LLM last year to support 10 major Indian languages. And KissanAI, co-founded by Pratik Desai, develops generative AI tools to deliver agricultural advice to farmers in their native languages.

The data dilemma

Yet building LLMs for underrepresented languages poses enormous challenges. Chief among them is data scarcity. “Even Hindi datasets are tiny compared to English,” says Tapas Kumar Mishra, a professor at the National Institute of Technology, Rourkela in eastern India. “So, training models from scratch is unlikely to match English-based models in performance.”

Rosman agrees. “The big-data paradigm doesn’t work for African languages. We simply don’t have the volume.” His team is pioneering alternative approaches like the Esethu Framework, a protocol for ethically collecting speech datasets from native speakers and redistributing revenue back to further development of AI tools for under-resourced languages. The project’s pilot used read speech from isiXhosa speakers, complete with metadata, to build voice-based applications.

In Arab nations, similar work is underway. Clusterlab’s 101 Billion Arabic Words Dataset is the largest of its kind, meticulously extracted and cleaned from the web to support Arabic-first model training.

The cost of staying local

But for all the innovation, practical obstacles remain. “The return on investment is low,” says KissanAI’s Desai. “The market for regional language models is big, but those with purchasing power still work in English.” And while Western tech companies attract the best minds globally, including many Indian and African scientists, researchers at home often face limited funding, patchy computing infrastructure, and unclear legal frameworks around data and privacy.

“There’s still a lack of sustainable funding, a shortage of specialists, and insufficient integration with educational or public systems,” warns Habib, the Cairo-based professor. “All of this has to change.”

A different vision for AI

Despite the hurdles, what’s emerging is a distinct vision for AI in the Global South – one that favours practical impact over prestige, and community ownership over corporate secrecy.

“There’s more emphasis here on solving real problems for real people,” says Nawale of AI4Bharat. Rather than chasing benchmark scores, researchers are aiming for relevance: tools for farmers, students, and small business owners.

And openness matters. “Some companies claim to be open-source, but they only release the model weights, not the data,” Marivate says. “With InkubaLM, we release both. We want others to build on what we’ve done, to do it better.”

In a global contest often measured in teraflops and tokens, these efforts may seem modest. But for the billions who speak the world’s less-resourced languages, they represent a future in which AI doesn’t just speak to them, but with them."

Sibusiso Biyela, Amr Rageh and Shakoor Rather

20 May 2025

https://www.natureasia.com/en/nmiddleeast/article/10.1038/nmiddleeast.2025.65

#metaglossia_mundus

"Nonbinary Hebrew transforms the language for everyone

As a living language, Hebrew is constantly evolving to adapt to the needs of its speakers. That must include nonbinary people too.

How do people who go by they/them pronouns in English refer to themselves in Hebrew? What do you call the Jewish rite of passage ceremony for a nonbinary tween? What plural words should we use for a group of people who each have a different gender?

I was faced with these wonderfully productive dilemmas when I studied Hebrew in college eight years ago. I had come out a year earlier as nonbinary, which means for me that my gender does not fit neatly into the boxes of man or woman. I asked Eyal Rivlin, my Hebrew professor at University of Colorado at Boulder, about the established conventions for nonbinary people. After he and I did research by asking friends, family and colleagues and examining literature, we realized there was no comprehensive system for speaking Hebrew without using the masculine or feminine.

We decided to experiment and created the Nonbinary Hebrew Project in 2018.

Hebrew is both ancient and modern. As a living language, it is constantly changing, evolving and growing to adapt to the needs of its speakers. It is used daily for conversation, prayer, ritual and study. As such, it is critical that everyone who needs or wants to use Hebrew can do so in a way that is affirming.

One of the aspects of Hebrew that distinguishes it from English is its use of what linguists call grammatical gender. English has some familiar uses of it, such as the personal pronouns she/her and he/him. But in many languages, including Hebrew, almost all parts of speech are gendered, including verbs, nouns and adjectives. This grammatical gender is often chosen based on the gender of the speaker or the subject of the sentence.

Some queer communities in Israel use “lashon me’orevet,” or “language that crosses over,” in which they intentionally challenge this convention by switching grammatical gender mid-sentence or in every other sentence for the same speaker or subject. This is affirming for many people — but I sought to create a third option for people like myself for whom the grammatical masculine or feminine did not entirely affirm my identity.

The system that Eyal and I created is intuitive to Hebrew speakers because it creates a third parallel system of grammatical gender for use alongside the masculine and feminine options.

In traditional Hebrew, for example, grammatically masculine words are usually considered the default, while grammatically feminine words often end with an additional “-et” or “-ah.” In our new, more expansive option, many singular nouns, verbs and adjectives end with “-eh” to distinguish them from the masculine or feminine.

In another example from traditional Hebrew, grammatically masculine plural words end in “-im,” with groups referred to with the pronouns “hem” or “atem,” while feminine plural words end in “-ot,” with groups referred to with “hen” or “aten.” In our new system, plural words can use the ending “-imot” or “-emen,” both of which combine existing plural endings and were already used by some people before our project.

Since the Nonbinary Hebrew Project’s creation, many people across the world have applied our system for their own uses, such as Yizkor (memorial) prayers, baby-naming ceremonies and wedding blessings. There are other innovations as well, such as using “bet mitzvot,” instead of a bar or bat mitzvah. I can now start the day with the prayer “Modet Ani” (rather than “modeh” or “modah”). And when I’m called to the Torah, I can receive a blessing that truly honors me.

Another application I have been excited to see is the use of our system to refer to the Divine without using the masculine or feminine.

There is a rich history in Hebrew texts of gender being used in playful ways, for both people and the Divine. Many names for the Divine, such as Rock or Fountain of Life, are already beyond traditional notions of binary gender.

The Nonbinary Hebrew Project opens up possibilities for radical joy, euphoria and recognition of the other as a sibling rather than a stranger. We connect with one another through shared language, and our project aims to provide another tool for weaving communities closer together.

If you’re interested in learning more, come to one of our workshops this Friday evening, June 6, at Congregation Sha’ar Zahav in San Francisco or stay tuned for our virtual workshops by checking the calendar at nonbinaryhebrew.com. You can find applied uses of the system on the website, as well as grammar charts, podcasts and news articles.

This Pride Month, and all year long, let’s find joy together by using language to uplift one another and honor each other’s light."

BY LIOR GROSS

JUNE 5, 2025

https://jweekly.com/2025/06/05/nonbinary-hebrew-transforms-the-language-for-everyone/

#metaglossia_mundus

"Amazon Lex extends custom vocabulary feature to additional languages

Posted on: Jun 4, 2025

Amazon Lex now extends custom vocabulary support to multiple languages, including Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, Catalan, French, German, and Spanish locales. This enhancement enables you to improve speech recognition accuracy for domain-specific terminology, proper nouns, and rare words across a wider range of languages, creating more natural and accurate conversational experiences. With custom vocabulary, you can provide Amazon Lex with specific phrases that should be recognized during audio conversations, even when the spoken audio might be ambiguous. For example, you can ensure technical terms like "Cognito" or industry-specific vocabulary like "solvency" are correctly transcribed during bot interactions, providing consistent speech recognition capabilities that work both for intent recognition and improving slot value elicitation.

This feature is now available in all AWS Regions where Amazon Lex operates for the supported languages."

https://aws.amazon.com/about-aws/whats-new/2025/06/amazon-lex-custom-vocabulary-additional-languages/

#metaglossia_mundus

Dans un futur proche, la proportion de données en langage naturel sur le Web pourrait diminuer au point d’être éclipsée par des textes générés par l’Intelligence artificielle.

Les agents conversationnels tels que ChatGPT facilitent parfois notre quotidien en prenant en charge des tâches rébarbatives. Mais ces robots intelligents ont un coût. Leur bilan carbone et hydrique désastreux est désormais bien connu. Un autre aspect très préoccupant l’est moins : l’intelligence artificielle pollue les écrits et perturbe l’écosystème langagier, au risque de compliquer l’étude du langage.

Une étude publiée en 2023 révèle que l’utilisation de l’intelligence artificielle (IA) dans les publications scientifiques a augmenté significativement depuis le lancement de ChatGPT (version 3.5). Ce phénomène dépasse le cadre académique et imprègne une part substantielle des contenus numériques, notamment l’encyclopédie participative Wikipedia ou la plate-forme éditoriale états-unienne Medium.

Le problème réside d’abord dans le fait que ces textes sont parfois inexacts, car l’IA a tendance à inventer des réponses lorsqu’elles ne figurent pas dans sa base d’entraînement. Il réside aussi dans leur style impersonnel et uniformisé.

La contamination textuelle par l’IA menace les espaces numériques où la production de contenu est massive et peu régulée (réseaux sociaux, forums en ligne, plates-formes de commerce…). Les avis clients, les articles de blog, les travaux d’étudiants, les cours d’enseignants sont également des terrains privilégiés où l’IA peut discrètement infiltrer des contenus générés et finalement publiés.

La tendance est telle qu’on est en droit de parler de pollution textuelle. Les linguistes ont de bonnes raisons de s’en inquiéter. Dans un futur proche, la proportion de données en langues naturelles sur le Web pourrait diminuer au point d’être éclipsée par des textes générés par l’IA. Une telle contamination faussera les analyses linguistiques et conduira à des représentations biaisées des usages réels du langage humain. Au mieux, elle ajoutera une couche de complexité supplémentaire à la composition des échantillons linguistiques que les linguistes devront démêler.

Read more: L’IA au travail : un gain de confort qui pourrait vous coûter cher

Quel impact sur la langue ?

Cette contamination n’est pas immédiatement détectable pour l’œil peu entraîné. Avec l’habitude, cependant, on se rend compte que la langue de ChatGPT est truffée de tics de langage révélateurs de son origine algorithmique. Il abuse aussi bien d’adjectifs emphatiques, tels que « crucial », « essentiel », « important » ou « fascinant », que d’expressions vagues (« de nombreux… », « généralement… »), et répond très souvent par des listes à puces ou numérotées. Il est possible d’influer sur le style de l’agent conversationnel, mais c’est le comportement par défaut qui prévaut dans la plupart des usages.

Un article de Forbes publié en décembre 2024 met en lumière l’impact de l’IA générative sur notre vocabulaire et les risques pour la diversité linguistique. Parce qu’elle n’emploie que peu d’expressions locales et d’idiomes régionaux, l’IA favoriserait l’homogénéisation de la langue. Si vous demandez à un modèle d’IA d’écrire un texte en anglais, le vocabulaire employé sera probablement plus proche d’un anglais global standard et évitera des expressions typiques des différentes régions anglophones.

L’IA pourrait aussi simplifier considérablement le vocabulaire humain, en privilégiant certains mots au détriment d’autres, ce qui conduirait notamment à une simplification progressive de la syntaxe et de la grammaire. Comptez le nombre d’occurrences des adjectifs « nuancé » et « complexe » dans les sorties de l’agent conversationnel et comparez ce chiffre à votre propre usage pour vous en rendre compte.

Du lundi au vendredi + le dimanche, recevez gratuitement les analyses et décryptages de nos experts pour un autre regard sur l’actualité. Abonnez-vous dès aujourd’hui !

Ce qui inquiète les linguistes

La linguistique étudie le langage comme faculté qui sous-tend l’acquisition et l’usage des langues. En analysant les occurrences linguistiques dans les langues naturelles, les chercheurs tentent de comprendre le fonctionnement des langues, qu’il s’agisse de ce qui les distingue, de ce qui les unit ou de ce qui en fait des créations humaines. La linguistique de corpus se donne pour tâche de collecter d’importants corpus textuels pour modéliser l’émergence et l’évolution des phénomènes lexicaux et grammaticaux.

Les théories linguistiques s’appuient sur des productions de locuteurs natifs, c’est-à-dire de personnes qui ont acquis une langue depuis leur enfance et la maîtrisent intuitivement. Des échantillons de ces productions sont rassemblés dans des bases de données appelées corpus. L’IA menace aujourd’hui la constitution et l’exploitation de ces ressources indispensables.

Pour le français, des bases comme Frantext (qui rassemble plus de 5 000 textes littéraires) ou le French Treebank (qui contient plus de 21 500 phrases minutieusement analysées) offrent des contenus soigneusement vérifiés. Cependant, la situation est préoccupante pour les corpus collectant automatiquement des textes en ligne. Ces bases, comme frTenTen ou frWaC, qui aspirent continuellement le contenu du Web francophone, risquent d’être contaminées par des textes générés par l’IA. À terme, les écrits authentiquement humains pourraient devenir minoritaires.

Les corpus linguistiques sont traditionnellement constitués de productions spontanées où les locuteurs ignorent que leur langue sera analysée, condition sine qua non pour garantir l’authenticité des données. L’augmentation des textes générés par l’IA remet en question cette conception traditionnelle des corpus comme archives de l’usage authentique de la langue.

Alors que les frontières entre la langue produite par l’homme et celle générée par la machine deviennent de plus en plus floues, plusieurs questions se posent : quel statut donner aux textes générés par l’IA ? Comment les distinguer des productions humaines ? Quelles implications pour notre compréhension du langage et son évolution ? Comment endiguer la contamination potentielle des données destinées à l’étude linguistique ?

Une langue moyenne et désincarnée

On peut parfois avoir l’illusion de converser avec un humain, comme dans le film « Her » (2013), mais c’est une illusion. L’IA, alimentée par nos instructions (les fameux « prompts »), manipule des millions de données pour générer des suites de mots probables, sans réelle compréhension humaine. Notre IA actuelle n’a pas la richesse d’une voix humaine. Son style est reconnaissable parce que moyen. C’est le style de beaucoup de monde, donc de personne.

Bande annonce du film « Her » (2013) de Spike Jonze.

À partir d’expressions issues d’innombrables textes, l’IA calcule une langue moyenne. Le processus commence par un vaste corpus de données textuelles qui rassemble un large éventail de styles linguistiques, de sujets et de contextes. Au fur et à mesure l’IA s’entraîne et affine sa « compréhension » de la langue (par compréhension, il faut entendre la connaissance du voisinage des mots) mais en atténue ce qui rend chaque manière de parler unique. L’IA prédit les mots les plus courants et perd ainsi l’originalité de chaque voix.

Bien que ChatGPT puisse imiter des accents et des dialectes (avec un risque de caricature), et changer de style sur demande, quel est l’intérêt d’étudier une imitation sans lien fiable avec des expériences humaines authentiques ? Quel sens y a-t-il à généraliser à partir d’une langue artificielle, fruit d’une généralisation déshumanisée ?

Parce que la linguistique relève des sciences humaines et que les phénomènes grammaticaux que nous étudions sont intrinsèquement humains, notre mission de linguistes exige d’étudier des textes authentiquement humains, connectés à des expériences humaines et des contextes sociaux. Contrairement aux sciences exactes, nous valorisons autant les régularités que les irrégularités langagières. Prenons l’exemple révélateur de l’expression « après que » : normalement suivie de l’indicatif, selon les livres de grammaire, mais fréquemment employée avec le subjonctif dans l’usage courant. Ces écarts à la norme illustrent parfaitement la nature sociale et humaine du langage.

La menace de l’ouroboros

La contamination des ensembles de données linguistiques par du contenu généré par l’IA pose de grands défis méthodologiques. Le danger le plus insidieux dans ce scénario est l’émergence de ce que l’on pourrait appeler un « ouroboros linguistique » : un cycle d’auto-consommation dans lequel les grands modèles de langage apprennent à partir de textes qu’ils ont eux-mêmes produits.

Cette boucle d’autorenforcement pourrait conduire à une distorsion progressive de ce que nous considérons comme le langage naturel, puisque chaque génération de modèles d’IA apprend des artefacts et des biais de ses prédécesseurs et les amplifie.

Il pourrait en résulter un éloignement progressif des modèles de langage humain authentique, ce qui créerait une sorte de « vallée de l’étrange » linguistique où le texte généré par l’IA deviendrait simultanément plus répandu et moins représentatif d’une communication humaine authentique."

https://theconversation.com/vocabulaire-et-diversite-linguistique-comment-lia-appauvrit-le-langage-252944

#metaglossia_mundus

"...BookTranslate.ai is the Gutenberg Revolution of translation.”— Balint Taborski EGER, HUNGARY, June 5, 2025 /EINPresswire.com/ -- BookTranslate.ai, a groundbreaking AI-powered literary translation platform, has outperformed legendary human translator Donald Keene in a blind test — and it’s now open to publishers, authors, and translators worldwide.

Unlike generic AI tools, BookTranslate.ai doesn’t just translate — it analyzes, refines, and critiques its own output across three advanced stages. The system includes a sophisticated AI Literary Analysis Engine, an Advanced Multi-Pass Refinement System, and a final-stage AI Review Engine (“The Finalizer”). This full-stack process delivers translations of exceptional fidelity and style — even surpassing acclaimed human translations in blind literary evaluations.

Founded by Hungarian indie publisher, translator, and software developer Balint Taborski (Praxeum Publishing), BookTranslate.ai emerged from the critical need for high-fidelity translations of complex literary and philosophical works. "Traditional translation is often prohibitively expensive and slow for small, niche, budget-constrained publishers like myself, while generic machine translation tools lacked the nuance for publishable quality," says Taborski. "I needed to cut costs without sacrificing quality. I needed a system that could not only translate with precision but also preserve authorial intent and literary integrity. What began as an internal tool has evolved into a platform that can empower authors and publishers worldwide."

BookTranslate.ai's unique three-stage process ensures unparalleled quality:

1. AI Literary Analysis Engine (Preprocessor): Before translation, this engine performs a deep, holistic analysis of the entire manuscript, understanding its genre, style, themes, and structure. It generates a custom "Translation Blueprint" – detailed instructions and an AI-suggested glossary – to guide the subsequent translation with unparalleled contextual awareness.

2. Advanced Multi-Pass Refinement System: Each paragraph, guided by the Blueprint, undergoes five distinct AI-driven passes of translation and proofreading. This iterative process refines grammar, fluency, tone, and stylistic consistency, aiming for output that is ~98% publication-ready.

3. AI Final Review Engine (The "Finalizer"): This final stage acts as an expert AI second opinion. The Finalizer meticulously compares the AI-translated text against the original source, identifying subtle errors, inconsistencies, or nuanced improvement opportunities that even a robust multi-pass system might overlook. Its suggestions, which users can review and selectively apply, further elevate the translation's polish towards perfection.

The platform's capabilities have been validated through multiple public demonstrations and blind tests. Notably, in an evaluation of Osamu Dazai's Ningen Shikkaku (No Longer Human), Google's Gemini 2.5 Pro model assessed BookTranslate.ai's translation as "Best," outperforming both DeepL and Donald Keene's acclaimed version, stating it "delivered the most fluent, faithful, and emotionally rich translation." Gemini also remarked, when reviewing BookTranslate.ai's unedited English translation of a 19th century classic of French political philosophy, Édouard Laboulaye’s *The State and Its Limits*, "Given the consistency and elegance, it's more straightforward to attribute it to a talented human translator."

Additional compelling case studies, including blind analyses of translations for works by H.P. Lovecraft and Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, demonstrating the system's versatility and the AI Finalizer's impact, are available on the BookTranslate.ai website.

"BookTranslate.ai is the Gutenberg Revolution of translation," Taborski adds. "It's not just about AI generating text; it's about AI demonstrating a deep literary understanding, refining its own work with meticulous care, and even providing critical editorial feedback. An entire AI editorial board is collaborating on the manuscript under the hood. This allows us to make great literature and important ideas accessible across languages at a fraction of the cost, without sacrificing quality. Soon, we will look upon traditional human translation much as we now look upon the hand-copying of books."

BookTranslate.ai invites authors, publishers, and translators to experience the future of literary translation. Full book examples, a free trial for up to 3000 characters, and an on-request full-chapter translation offer are available at https://booktranslate.ai.

About BookTranslate.ai:

BookTranslate.ai is an advanced AI translation platform specializing in books and long-form texts. Its proprietary three-stage system—comprising pre-translation literary analysis, multi-pass AI refinement, and an AI final review engine—delivers publishable-quality translations that preserve authorial voice and nuance. Founded by indie publisher Balint Taborski, BookTranslate.ai aims to democratize access to global literature and ideas.

Balint Taborski

BookTranslate.ai

+36 70 218 1428

hello@booktranslate.ai

https://www.pahomepage.com/business/press-releases/ein-presswire/819508395/booktranslate-ai-stuns-publishing-world-ai-outperforms-legendary-translator-in-blind-test/

#metaglossia_mundus

"TransPerfect Launches New App for Mobile Interpretation

Supports Intuitive Access to a Phone or Video Interpreter in Seconds

NEW YORK, June 05, 2025 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- TransPerfect, the world's largest provider of language and AI solutions for global business, today announced it has launched the TransPerfect Interpretation App, enabling users to connect to a live, expertly trained video or phone interpreter in seconds.

Available on the web, iOS, Android, and Microsoft devices, the app makes accessing over-the-phone interpretation and video remote interpretation simple and fast. It supports 200+ languages, including American Sign Language, enabling users across multiple industries to quickly and effectively respond to customer needs. It’s ideal for hospitals, medical and benefit providers, financial branches, legal, retail stores, first responders, and others in any situation where customer interactions happen outside of a contact center.

“This app marks a significant leap forward in making interpretation services more accessible and easier to use,” commented TransPerfect Connect Vice President Steven Cheeseman. “With on-demand access to professional interpreters, we’re empowering organizations to overcome language barriers in real time. It’s fast, intuitive, and purpose-built to support the critical work our clients perform every day.”

To use the app, simply select a language from the menu and tap to choose audio or video interpretation. If a video interpreter is not available, the call will automatically route to an audio interpreter.

Available to all existing TransPerfect customers, the app enables users to:

Capture necessary data (account numbers, claim numbers, medical record numbers, etc.)

Adjust the audio, mute lines, turn video on and off

Add additional parties regardless of whether they have the application installed

Capture user satisfaction at the end of every call (customizable by client)

TransPerfect President and Co-CEO Phil Shawe stated, “TransPerfect customers now have easy access to a live interpreter—wherever, whenever, and in any language.”

To learn more about the launch, visit https://go.transperfect.com/mobile_interpretation or email us at mobileinterp@transperfect.com..."

June 05, 2025 10:00 ET

| Source: TransPerfect

https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2025/06/05/3094498/0/en/TransPerfect-Launches-New-App-for-Mobile-Interpretation.html

#metaglossia_mundus

Google reveals details behind the development of AI Mode. Learn design insights and what marketers need to know.

Google built AI Mode to handle longer, conversational search queries.

Google claims AI search delivers "more qualified clicks."

Google has no data to share to verify claims of quality improvements.

SEJ STAFF

Matt G. Southern

Google has shared new details about how it designed and built AI Mode.

In a blog post, the company reveals the user research, design challenges, and testing that shaped its advanced AI search experience.

These insights may help you understand how Google creates AI-powered search tools. The details show Google’s shift from traditional keyword searches to natural language conversations.

User Behavior Drove AI Mode Creation

Google built AI Mode in response to the ways people were using AI Overviews.

Google’s research showed a disconnect between what searchers wanted and what was available.

Claudia Smith, UX Research Director at Google, explains:

“People saw the value in AI Overviews, but they didn’t know when they’d appear. They wanted them to be more predictable.”

The research also found people started asking longer questions. Traditional search wasn’t built to handle these types of queries well.

This shift in search behavior led to a question that drove AI Mode’s creation, explains Product Management Director Soufi Esmaeilzadeh:

“How do you reimagine a Search gen AI experience? What would that look like?”

AI “Power Users” Guided Development Process

Google’s UX research team identified the most important use cases as: exploratory advice, how-to guides, and local shopping assistance.

This insight helped the team understand what people wanted from AI-powered search.

Esmaeilzadeh explained the difference:

“Instead of relying on keywords, you can now pose complex questions in plain language, mirroring how you’d naturally express yourself.”

According to Esmaeilzadeh, early feedback suggests that the team’s approach was successful:

“They appreciate us not just finding information, but actively helping them organize and understand it in a highly consumable way, with help from our most intelligent AI models.”

Industry Concerns Around AI Mode

While Google presents an optimistic development story, industry experts are raising valid concerns.

John Shehata, founder of NewzDash, reports that sites are already “losing anywhere from 25 to 32% of all their traffic because of the new AI Overviews.” For news publishers, health queries show 26% AI Overview penetration.

Mordy Oberstein, founder of Unify Brand Marketing, analyzed Google’s I/O demonstration and found the examples weren’t as complex as presented. He shows how Google combined readily available information rather than showcasing advanced AI reasoning.

Google’s claims about improved user engagement have not been verified. During a recent press session, Google executives claimed AI search delivers “more qualified clicks” but admitted they have “no data to share” on these quality improvements.

Further, Google’s reporting systems don’t differentiate between clicks from traditional search, AI overviews, and AI mode. This makes independent verification impossible.

Shehata believes that the fundamental relationship between search and publishers is changing:

“The original model was Google: ‘Hey, we will show one or two lines from your article, and then we will give you back the traffic. You can monetize it over there.’ This agreement is broken now.”

What This Means

For SEO professionals and content marketers, Google’s insights reveal important changes ahead.

The shift from keyword targeting to conversational queries means content strategies need to focus on directly answering user questions rather than optimizing for specific terms.

The focus on exploratory advice, how-to content, and local help shows these content types may become more important in AI Mode results.

Shehata recommends that publishers focus on content with “deep analysis of a situation or an event” rather than commodity news that’s “available on hundreds and thousands of sites.”

He also notes a shift in success metrics: “Visibility, not traffic, is the new metric” because “in the new world, we will get less traffic.”

Looking Ahead

Esmaeilzadeh said significant work continues:

“We’re proud of the progress we’ve made, but we know there’s still a lot of work to do, and this user-centric approach will help us get there.”

Google confirmed that more AI Mode features shown at I/O 2025 will roll out in the coming weeks and months. This suggests the interface will keep evolving based on user feedback and usage patterns."

Matt G. Southern

Senior News Writer at Search Engine Journal

https://www.searchenginejournal.com/google-shares-details-behind-ai-mode-development/548474/

#metaglossia_mundus

Ngũgĩ’s most important contributions were on language. His novels, his essays, and his unyielding belief in the dignity of African languages reshaped world literature. To call him merely a “great African writer” would be to shrink his genius – he was one of the most vital thinkers of our age, a voice who spoke from Kenya but to humanity.

"Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o: The Writer Who Made Language a Battlefield

Ngũgĩ’s most important contributions were on language. His novels, his essays, and his unyielding belief in the dignity of African languages reshaped world literature. To call him merely a “great African writer” would be to shrink his genius – he was one of the most vital thinkers of our age, a voice who spoke from Kenya but to humanity.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, the literary giant from Kenya and unflinching advocate for African languages, passed away on 28 May 2025, leaving behind a legacy that bridged continents and generations. For those of us who knew him – whether through his words or in solidarity campaigns – his life was a testament to the power of art as resistance.

I am deeply saddened to learn of Ngũgĩ’s passing. Ngũgĩ did not just write books – he declared war. War on colonialism and neocolonialism, on linguistic shame, on the very idea that African thought must be filtered through colonial grammar to be “literature”. Always assuming that we would soon have our next conversation, I felt bereft when news of his death broke.

When I helped organise London protests for his release in 1978, we shouted his banned titles outside Kenya’s High Commission. We prepared banners saying “Kenyatta sheds Petals of Blood”, Waingereza walifunga Kimathi, Mzee anafunga Ngũgĩ! (The British locked up Kimathi, Mzee [Kenyatta] locks up Ngũgĩ!). Years later, when I visited him at his home near Kamĩrĩĩthu, the site of the people’s theatre at which Ngaahika Ndeenda was performed, and which the regime destroyed, he told me: “You thought you were demanding my freedom? You were demanding yours.” He showed me the manuscript he’d written on scraps of paper while in prison. “They gave me a pen to confess,” he laughed. “I used it to imagine”. “They thought they buried me in prison,” he laughed, “but they planted a seed”. His warmth and clarity in person mirrored the fearlessness of his writing.

I always resented the fact that so much of his writing was relegated to the African Writers Series. True, the series brought attention to the wealth of writers from the African continent. But many of them were, like Ngũgĩ, literary giants, not merely “African writers”. Their contribution to art, politics, and thinking were and are of universal relevance. The failure to recognise this universalism is perhaps one of the reasons that, despite being nominated several times, Ngũgĩ was denied the Nobel prize for literature.

Ngũgĩ’s most important contributions were on language. His novels, his essays, and his unyielding belief in the dignity of African languages reshaped world literature. To call him merely a “great African writer” would be to shrink his genius – he was one of the most vital thinkers of our age, a voice who spoke from Kenya but to humanity. Ngũgĩ’s decision to write in Gĩkũyũ was not symbolic – it was an act of intellectual insurrection. He tore down the lie that creativity required the approval of imperial languages. “To think in my mother tongue,” he once told me, “is to dream in freedom”. His Gĩkũyũ works (Mũrogi wa Kagogo, Matigari) were not “translations from English” – they were the originals, the canon itself. Beyond “African Writer”, Western obituaries will box him into “African literature”. But Ngũgĩ belonged to the same pantheon as Dostoevsky, Marquez, and Orwell – writers who exposed the machinery of power. Wizard of the Crow is as universal as 1984; Decolonising the Mind, perhaps as urgent as Fanon.

In his Foreword to the Daraja Press edition of Mau Mau From Within: The Story of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army, Ngũgĩ wrote: “We don’t have to use the vocabulary of the colonial to describe our struggles, especially today when there is a worldwide movement to overturn monuments to slavery and colonialism.”

For those of us who stood beside Ngũgĩ – in protest, in lecture halls, or in his Limuru home – he was also a generous comrade, always leaning forward to listen, even as the world often leaned away from him. I admired how attentive Ngũgĩ always was to aspiring younger writers. At conferences where we both spoke, I watched him corner young African writers, urging them to “write dangerously”. He’d ask: “Who owns your language? Who profits from your silence?” His belief in them was visceral. “Talent is common,” he told them, “What’s rare is the courage to use it.”

In his piercing 2020 interview with Daraja Press, Ngũgĩ laid bare his life’s mission: Colonialism” stole our land, but language was the theft of our dreams”. He recounted how, as a child, British teachers beat Gĩkũyũ out of his classmates–”not just with canes, but with the lie that our words were small, ugly things”. His entire oeuvre, from his early writings as “James” Ngugi, to Petals of Blood, Decolonising the Mind and Wizard of the Crow, was a counterattack: “I write in Gĩkũyũ not to be provincial, but to prove that the universal lives in the particular.”

Kenya today claims Ngũgĩ as a national treasure – yet how recklessly it squandered him in his prime. No streets are named for the man whose books were banned in schools, politicians quote Decolonising the Mind while gutting funding for indigenous-language education. When I last visited Nairobi, a young poet told me, “They praise Ngũgĩ now because he’s no longer dangerous.” But Ngũgĩ’s legacy is danger: the kind that outlives regimes.

Kiumbi kiaguo ikio ki, kiaguo ikio. “A thing that forgets its origins will soon die.” Ngũgĩ, they jailed you, exiled you, misnamed you – yet here you remain.

Rest well, comrade and friend.

Sincere condolences to Ngugi’s family."

Firoze Manji

June 5, 2025

https://www.theelephant.info/opinion/2025/06/05/ngugi-wa-thiongo-the-writer-who-made-language-a-battlefield/

#metaglossia_mundus

En rompant avec l’anglais pour écrire en kikuyu, il a incarné une pensée radicale de la décolonisation.

"L'héritage vivant de Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o : décoloniser l’esprit et les langues

Published: June 5, 2025 3.59pm SAST

Christophe Premat, Stockholm University

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o est mort le 28 mai 2025 à l’âge de 87 ans. Son nom restera dans l’histoire non seulement comme celui d’un grand romancier kenyan, mais aussi comme celui d’un penseur radical de la décolonisation. À l’instar de Valentin-Yves Mudimbe, disparu quelques semaines plus tôt, il a su interroger les conditions mêmes de la possibilité d’un savoir africain en contexte postcolonial. Mais là où Mudimbe scrutait les « bibliothèques coloniales » pour en dévoiler les présupposés, Ngũgĩ a voulu transformer la pratique même de l’écriture : en cessant d’écrire en anglais pour privilégier sa langue maternelle, le kikuyu, il a posé un geste politique fort, un acte de rupture.

En tant que spécialiste des théories postcoloniales, j'analyse la manière dont ces parcours critiques se sont efforcés à repenser la manière dont le savoir est produit et transmis en Afrique.

Pour Ngũgĩ, la domination coloniale ne s’arrête pas aux frontières, aux institutions ou aux lois. Elle prend racine dans les structures mentales, dans la manière dont un peuple se représente lui-même, ses valeurs, son passé, son avenir.

Langue et pouvoir : une géopolitique de l’imaginaire

Dans Décoloniser l’esprit (1986), Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o explique pourquoi il a décidé d’abandonner l’anglais, langue dans laquelle il avait pourtant connu un succès international. Il y pose une affirmation devenue centrale dans les débats sur les héritages coloniaux : « Les vrais puissants sont ceux qui savent leur langue maternelle et apprennent à parler, en même temps, la langue du pouvoir. » Car tant que les Africains seront contraints de penser, de rêver, d’écrire dans une langue qui leur a été imposée, la libération restera incomplète.

À travers la langue, les colonisateurs ont conquis bien plus que des terres : ils ont imposé une certaine vision du monde. En contrôlant les mots, ils ont contrôlé les symboles, les récits, les hiérarchies culturelles. Pour Ngũgĩ, le bilinguisme colonial ne relève pas d’un enrichissement, mais d’une fracture : il sépare la langue du quotidien (la langue vernaculaire) de celle de l’école, de la pensée, du droit, de la littérature. Il y voit une violence structurelle, une « dissociation entre l’esprit et le corps », qui rend impossible une appropriation pleine et entière de l’expérience africaine.

Une aliénation tenace

L’analyse de Ngũgĩ met en lumière les impasses des politiques linguistiques postcoloniales qui ont souvent continué à faire des langues européennes des langues d’État, de savoir et de prestige, tout en reléguant les langues africaines à la sphère privée. C’est en ce sens qu’on peut parler de diglossie, c’est-à-dire de situation de cohabitation de deux langues avec des fonctions sociales distinctes. Cette diglossie instituée produit une hiérarchisation des langues qui reflète, en profondeur, une hiérarchisation des cultures.

We’re 10! Support us to keep trusted journalism free for all.

Support our cause

Loin d’en appeler à un retour passéiste ou à une clôture identitaire, Ngũgĩ veut libérer le potentiel des langues africaines : leur permettre de dire le contemporain, d’inventer une modernité qui ne soit pas un simple calque des modèles européens. Il reprend ici à son compte la tâche historique que se sont donnée les écrivains dans d’autres langues « mineures » : faire pour le kikuyu ce que Shakespeare a fait pour l’anglais, ou Tolstoï pour le russe.

Il s’agit non seulement d’écrire dans les langues africaines, mais de faire en sorte que ces langues deviennent des vecteurs de philosophie, de sciences, d’institutions — bref, de civilisation. Ce choix d’écrire en kikuyu ne fut pas sans conséquences. En 1977, Ngũgĩ coécrit avec Ngũgĩ wa Mirii une pièce de théâtre, Ngaahika Ndeenda (« Je me marierai quand je voudrai »), jouée en langue kikuyu dans un théâtre communautaire de Kamiriithu, près de Nairobi.

La pièce, portée par des acteurs non professionnels, dénonçait avec virulence les inégalités sociales et les survivances du colonialisme au Kenya. Son succès populaire inquiète les autorités : quelques semaines après la première, Ngũgĩ est arrêté sans procès et incarcéré pendant près d’un an. À sa libération, interdit d’enseigner et surveillé de près, il choisit l’exil.

Ce bannissement de fait durera plus de vingt ans. C’est dans cette période de rupture qu’il entame l’écriture en kikuyu de son roman Caitaani Mutharaba-Ini (Le Diable sur la croix), qu’il rédige en prison sur du papier hygiénique.

Une pensée toujours actuelle

L’œuvre de Ngũgĩ éclaire la manière dont les sociétés africaines contemporaines restent prises dans des logiques de domination symbolique, malgré les indépendances politiques. La mondialisation a remplacé les formes les plus brutales de l’impérialisme, mais elle reconduit souvent les logiques de domination symbolique. Dans le champ culturel, les ex-puissances coloniales continuent d’exercer une influence considérable à travers les réseaux diplomatiques, éducatifs, éditoriaux.

La Francophonie, par exemple, se présente comme un espace de coopération linguistique, mais elle perpétue souvent des asymétries dans la validation des productions culturelles. Le fait de présenter les langues coloniales comme des langues de communication dépassant les clôtures des langues vernaculaires est une illusion que Ngũgĩ dénonce avec virulence.

Des penseurs comme Jean-Godefroy Bidima ou Seloua Luste Boulbina ont montré à quel point les politiques linguistiques postcoloniales ont tendance à officialiser certaines langues au détriment d’autres, créant une nouvelle forme de langue de bois, souvent coupée des réalités populaires. La philosophe algéro-française évoque à ce propos un espace public plurilingue à instituer: un espace qui ne se résume pas à opposer langues coloniales et langues vernaculaires, mais qui réinvente les usages, les hybridations, les ruses du langage.

Cette réflexion fait écho à la position de Ngũgĩ : écrire dans sa langue ne suffit pas, encore faut-il produire un langage à la hauteur des luttes sociales et politiques.

Pour une mémoire active de Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

À l’heure où les débats sur la décolonisation se multiplient, souvent vidés de leur substance ou récupérés par des logiques institutionnelles, relire Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o permet de revenir à l’essentiel : l’émancipation passe par un changement de regard sur soi-même, qui commence dans la langue. La véritable libération n’est pas seulement politique ou économique ; elle est aussi culturelle, cognitive, symbolique.

En refusant de penser depuis des catégories importées, en assumant le risque d’un geste radical, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o a ouvert la voie à une pensée authentiquement africaine, enracinée et universelle. Son œuvre rappelle qu’il ne suffit pas de parler au nom de l’Afrique ; encore faut-il parler depuis elle, avec ses langues, ses imaginaires, ses luttes. À l’heure de sa disparition, son message reste plus vivant que jamais."

https://theconversation.com/lheritage-vivant-de-ngugi-wa-thiongo-decoloniser-lesprit-et-les-langues-258209

#metaglossia_mundus

"New York, the World’s Most Linguistically Diverse Metropolis

In Language City, Ross Perlin, a linguist, takes readers on a tour of the city’s communities with endangered tongues.

June 05, 2025

As co-director of the Endangered Language Alliance, Ross Perlin has managed a variety of projects focused on language documentation, language policy, and public programming around urban linguistic diversity. Photo by Cecil Howell.

Half of all 7,000-plus human languages may disappear over the next century, and—because many have never been recorded—when they’re gone, it will be forever. Ross Perlin, a lecturer in Columbia’s Department of Slavic Languages and co-director of the Endangered Language Alliance, is racing against time to map little-known languages across New York. In his new book, Language City, Perlin follows six speakers of endangered languages deep into their communities, from the streets of Brooklyn and Queens to villages on the other side of the world, to learn how they are maintaining and reviving their languages against overwhelming odds. He explores the languages themselves, from rare sounds to sentence-long words to bits of grammar that encode entirely different worldviews.

Seke is spoken by 700 people from five ancestral villages in Nepal, and a hundred others living in a single Brooklyn apartment building. N’ko is a radical new West African writing system now going global in Harlem and the Bronx. After centuries of colonization and displacement, Lenape, the city’s original indigenous language and the source of the name Manhattan, “the place where we get bows,” has just one native speaker, along with a small band of revivalists. Also profiled in the book are speakers of the indigenous Mexican language Nahuatl, the Central Asian minority language Wakhi, and Yiddish, braided alongside Perlin’s own complicated family legacy. On the 100th anniversary of a notorious anti-immigration law that closed America’s doors for decades, and the 400th anniversary of New York’s colonial founding, Perlin raises the alarm about growing political threats and the onslaught of languages like English and Spanish.

Perlin talks about the book with Columbia News, along with why New York is so linguistically diverse, and his current and upcoming projects.

How did this book come about?

I’m a linguist, writer, and translator, and have been focused on language endangerment and documentation for the last two decades. Initially, I worked in southwest China on a dictionary, a descriptive grammar, and corpus of texts for Trung, a language spoken in a single remote valley on the Burmese border. While finishing up my dissertation, I came back to New York and joined the Endangered Language Alliance (ELA), which had recently been founded to focus on urban linguistic diversity.

ELA’s key insight was a paradox: Even as language loss accelerates everywhere—with as many as half of the world’s 7,000 languages now considered endangered—cities are more linguistically diverse than ever before, thanks to migration, urbanization, and diaspora. This means that speakers of endangered, indigenous, and primarily oral languages are now often right next door, and that fieldwork can happen in a different key, with linguists and communities making common cause as neighbors, for the long term.

For the last 12 years, I’ve been ELA’s co-director, together with Daniel Kaufman. Leading a small, independent nonprofit has been its own adventure. We do everything from in-depth research on little-studied languages (projects on Jewish, Himalayan, and indigenous Latin American languages, for example, with much of the research happening right here in the five boroughs) to public events, classes, collaborations with city agencies, childrens books, and the first-ever language map of New York City. At some point, I knew that all my notes on everything I was learning and seeing around the city and beyond had to become a book. The urgency only grew as a series of unprecedented crises started hitting the immigrant and diaspora communities we work with. The crises are still unfolding.

Can you share some details about the six people you portray in the book, and the endangered languages they speak?

Language City is both the story of New York’s languages—the past, present, and future of the world's most linguistically diverse city—and the story of six specific people doing extraordinary things to keep their embattled mother tongues alive. They come from all over the world, but converge in New York. They represent a variety of strategies for language maintenance and revitalization in the face of tremendous odds. All of them are people I’ve known and worked with for years. Between them, in all their multilingualism, they actually speak about 30 languages, but they are also regular people you might run into on the subway.

Rasmina is one of the youngest speakers of Seke, a language from five villages in Nepal, and now a sixth, vertical village in the middle of Brooklyn. Husniya, a speaker of Wakhi from Tajikistan, has gone through every stage of her life and education in a different language, and can move easily along New York City’s new Silk Road. Originally from Moldova, Boris is a Yiddish novelist, poet, editor, and one-man linguistic infrastructure.

Ibrahima, a language activist from Guinea, champions N’ko, a relatively new writing system created to challenge the dominance of colonial languages in West Africa. Irwin is a Queens chef who writes poetry in, and cooks through, his native Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. And Karen is a keeper of Lenape, the original language of the land on which New York was settled.

How did New York end up as such a linguistically diverse city?

Four hundred years ago, this Lenape-speaking archipelago became nominally Dutch under the West India Company. In fact, the territory evolved into an unusual commercial entrepôt at the fulcrum of three continents, where the languages of Native Americans, enslaved Africans, and European refugees and traders were all in the mix. A reported 18 languages were spoken by the first 400-500 inhabitants. This set the template, but the defining immigration waves of the 19th and 20th centuries were of another order, as New York became a global center for business, politics, and culture, as well as the pre-eminent gateway to the U.S. and a bridge between hemispheres. From the half-remembered myth of Ellis Island to the very present reality of 200,000 asylum seekers arriving in the last few years, I argue—in what I think is the first linguistic history of any city—that applying the lens of language helps us understand the city (and all cities) in profoundly new ways. From Frisian and Flemish 400 years ago, to Fujianese and Fulani today, deep linguistic diversity, although always overlooked, has been fundamental.

What did you teach in the spring semester?

The class I’ve taught every year for the last six years—Endangered Languages in the Global City. I designed it around our research at ELA, and it’s completely unique to Columbia. Hundreds of students sign up, testifying to the massive interest Columbia students have in learning about linguistic diversity, though we can admit only a fraction of them. Many of the endangered language speakers and activists featured in Language City have visited the class, and we also take students out to some of the city’s most linguistically diverse neighborhoods, where many students have done strikingly original fieldwork.

The spring semester was something of a departure: I stepped in to teach Language and Society, as well as a course I designed last year called Languages of Asia, which focuses on the continent’s lesser-known language families and linguistic areas. I’ve also been supervising senior theses together with Meredith Landman,who directs the undergraduate program in linguistics. Across the first half of the 20th century, Columbia and Barnard became foundational sites for the study of linguistic diversity and for documenting languages, thanks to Franz Boas, who, in 1902, became the head of Columbia’s anthropology department—the first in the country—and his students. There is hope today for Columbia’s formative role to be revived: The University's local and global position makes this as urgent and achievable as ever. Additionally, the linguistics major was recently (at last) restored, and an ever-growing number of students are doing remarkable work on languages from around the world.

What are you working on now?

ELA keeps on ELA’ing, with a huge range of projects. On any given day, we might be recording and working with speakers of languages originally from Guatemala, Nepal, or Iran. With 700+ languages and counting, our language map (languagemap.nyc) is continually being updated, and we have people here making connections between language and health, education, literacy, technology, translation. This fall, I’ll be in Berlin as a fellow of the American Academy, researching via an obscure film (in 2,000 languages and counting) how missionary linguists and Bible translators shape global linguistic diversity.

Any summer plans related to language preservation at Columbia or elsewhere?

Ongoing work at ELA: The sky, if not for the budget, would be the limit. There have been recent sessions on a little-known language from Afghanistan, with a woman who is probably the only speaker in New York. Someone whose family still remembers a highly endangered Jewish language variant from Iran recently got in touch. And we met a speaker of a Mongolic language of western China at a restaurant. I also hope to continue soon some scouting of urban linguistic diversity in the Caucasus, past and present, with support from the Harriman Institute."

https://news.columbia.edu/news/new-york-worlds-most-linguistically-diverse-metropolis

#metaglossia_mundus

"Newswise — Creativity often emerges from the interplay of disparate ideas—a phenomenon known as combinational creativity. Traditionally, tools like brainstorming, mind mapping, and analogical thinking have guided this process. Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) introduces new avenues: large language models (LLMs) offer abstract conceptual blending, while image (T2I) and T2-three-dimensional (3D) models turn text prompts into vivid visuals or spatial forms. Yet despite their growing use, little research has clarified how these tools function across different stages of creativity. Without a clear framework, designers are left guessing which AI tool fits best. Given this uncertainty, in-depth studies are needed to evaluate how various AI dimensions contribute to the creative process.

A research team from Imperial College London, the University of Exeter, and Zhejiang University has tackled this gap. Their new study (DOI: 10.1016/j.daai.2025.100006), published in May 2025 in Design and Artificial Intelligence, investigates how generative AI models with different dimensional outputs support combinational creativity. Through two empirical studies involving expert and student designers, the team compared the performance of LLMs, T2I, and T2-3D models across ideation, visualization, and prototyping tasks. The results provide a practical framework for optimizing human-AI collaboration in real-world creative settings.

To map AI's creative potential, the researchers first asked expert designers to apply each AI type to six combinational tasks—including splicing, fusion, and deformation. LLMs performed best in linguistic-based combinations such as interpolation and replacement but struggled with spatial tasks. In contrast, T2I and T2-3D excelled at visual manipulations, with 3D models especially adept at physical deformation. In a second study, 24 design students used one AI type to complete a chair design challenge. Those using LLMs generated more conceptual ideas during early, divergent phases but lacked visual clarity. T2I models helped externalize these ideas into sketches, while T2-3D tools offered robust support for building and evaluating physical prototypes. The results suggest that each AI type offers unique strengths, and the key lies in aligning the right tool with the right phase of the creative process.

“Understanding how different generative AI models influence creativity allows us to be more intentional in their application,” said Prof. Peter Childs, co-author and design engineering expert at Imperial College London. “Our findings suggest that large language models are better suited to stimulate early-stage ideation, while text-to-image and text-to-3D tools are ideal for visualizing and validating ideas. This study helps developers and designers align AI capabilities with the creative process rather than using them as one-size-fits-all solutions.”

The study's insights are poised to reshape creative workflows across industries. Designers can now match AI tools to specific phases—LLMs for generating diverse concepts, T2I for rapidly visualizing designs, and T2-3D for translating ideas into functional prototypes. For educators and AI developers, the findings provide a blueprint for building more effective, phase-specific design tools. By focusing on each model’s unique problem-solving capabilities, this research elevates the conversation around human–AI collaboration and paves the way for smarter, more adaptive creative ecosystems.

###

References

DOI

10.1016/j.daai.2025.100006

Original Source URL

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.daai.2025.100006

Funding information

The first and third authors would like to acknowledge the China Scholarship Council (CSC)."

Released: 5-Jun-2025 7:35 AM EDT

Source Newsroom: Chinese Academy of Sciences

https://www.newswise.com/articles/designing-with-dimensions-rethinking-creativity-through-generative-ai

##metaglossia_mundus

"AI reveals hidden language patterns and likely authorship in the Bible

by Duke University

edited by Sadie Harley, reviewed by Robert Egan

AI is transforming every industry, from medicine to film to finance. So, why not use it to study one of the world's most revered ancient texts, the Bible?

An international team of researchers, including Shira Faigenbaum-Golovin, assistant research professor of Mathematics at Duke University, combined artificial intelligence, statistical modeling and linguistic analysis to address one of the most enduring questions in biblical studies: the identification of its authors.

The study is published in the journal PLOS One.

By analyzing subtle variations in word usage across texts, the team was able to distinguish between three distinct scribal traditions (writing styles) spanning the first nine books of the Hebrew Bible, known as the Enneateuch.

Using the same AI-based statistical model, the team was then able to determine the most likely authorship of other Bible chapters. Even better, the model also explained how it reached its conclusions.

But how did the mathematician get here?

In 2010, Faigenbaum-Golovin began collaborating with Israel Finkelstein, head of the School of Archaeology and Maritime Cultures at the University of Haifa, using mathematical and statistical tools to determine the authorship of lettering found on pottery fragments from 600 B.C. by comparing the style and shape of the letters inscribed on each fragment.

Their discoveries were featured on the front page of The New York Times.

"We concluded that the findings in those inscriptions could offer valuable clues for dating texts from the Old Testament," Faigenbaum-Golovin said. "That's when we started putting together our current team, who could help us analyze these biblical texts."

The multidisciplinary undertaking was made up of two parts. First, Faigenbaum-Golovin and Finkelstein's team—Alon Kipnis (Reichman University), Axel Bühler (Protestant Faculty of Theology of Paris), Eli Piasetzky (Tel Aviv University) and Thomas Römer (Collège de France)—was made up of archaeologists, biblical scholars, physicists, mathematicians and computer scientists.

The team used a novel AI-based statistical model to analyze language patterns in three major sections of the Bible. They studied the Bible's first five books: Deuteronomy, the so-called Deuteronomistic History from Joshua to Kings, and the priestly writings in the Torah.

Results showed Deuteronomy and the historical books were more similar to each other than to the priestly texts, which is already the consensus among biblical scholars.

"We found that each group of authors has a different style—surprisingly, even regarding simple and common words such as 'no,' 'which,' or 'king.' Our method accurately identifies these differences," said Römer.

To test the model, the team selected 50 chapters from the first nine books of the Bible, each of which has already been allocated by biblical scholars to one of the writing styles mentioned above.

"The model compared the chapters and proposed a quantitative formula for allocating each chapter to one of the three writing styles," said Faigenbaum-Golovin.

In the second part of the study, the team applied their model to chapters of the Bible whose authorship was more hotly debated. By comparing these chapters to each of the three writing styles, the model was able to determine which group of authors was more likely to have written them. Even better: the model also explained why it was making these calls.

"One of the main advantages of the method is its ability to explain the results of the analysis—that is, to specify the words or phrases that led to the allocation of a given chapter to a particular writing style," said Kipnis.

Since the text in the Bible has been edited and re-edited many times, the team faced big challenges finding segments that retained their original wording and language.

Once found, these biblical texts were often very short—sometimes just a few verses—which made most standard statistical methods and traditional machine learning unsuitable for their analysis. They had to develop a custom approach that could handle such limited data.

Limited data often brings fears of inaccuracy. "We spent a lot of time convincing ourselves that the results we were getting weren't just garbage," said Faigenbaum-Golovin. "We had to be absolutely sure of the statistical significance."

To circumvent the issue, instead of using traditional machine learning, which requires lots of training data, the researchers used a simpler, more direct method. They compared sentence patterns and how often certain words or word roots (lemmas) appeared in different texts, to see if they were likely written by the same group of authors.

A surprising find? The team discovered that although the two sections of the Ark Narrative in the Books of Samuel address the same theme and are sometimes regarded as parts of a single narrative, the text in 1 Samuel does not align with any of the three corpora, whereas the chapter in 2 Samuel shows affinity with the Deuteronomistic History (Joshua to Kings).

Looking forward, Faigenbaum-Golovin said the same technique can be used for other historical documents. "If you're looking at document fragments to find out if they were written by Abraham Lincoln, for example, this method can help determine if they are real or just a forgery."

"The study introduces a new paradigm for analyzing ancient texts," summarized Finkelstein.

Faigenbaum-Golovin and her team are now looking at using the same methodology to unearth new discoveries about other ancient texts, like the Dead Sea Scrolls. She emphasized how much she enjoyed the long-term cross-disciplinary partnership.

"It's such a unique collaboration between science and the humanities," she said. "It's a surprising symbiosis, and I'm lucky to work with people who use innovative research to push boundaries."

More information: Shira Faigenbaum-Golovin et al, Critical biblical studies via word frequency analysis: Unveiling text authorship, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0322905

Journal information: PLoS ONE"

https://phys.org/news/2025-06-ai-reveals-hidden-language-patterns.html

#metaglossia_mundus

Depuis 25 ans, le programme Goldschmidt a formé près de 250 traducteurs et traductrices, contribuant à structurer un réseau international au service des échanges littéraires entre espaces francophones et germanophones...

"Goldschmidt : 25 ans au service des jeunes traducteurs littéraires

Jeudi 12 juin 2025, au Goethe-Institut de Paris, le programme Georges-Arthur Goldschmidt fête son quart de siècle. Créé en 2000 pour accompagner les jeunes traducteurs littéraires, ce dispositif, désormais franco-germano-suisse et, pour la première fois cette année, autrichien, marque un tournant avec une soirée dédiée à la traduction, à ses défis contemporains et à ses figures marquantes.

Le 05/06/2025 à 13:20 par Dépêche

Soutenu par l’OFAJ, France Livre, la Foire de Francfort, Pro Helvetia et le ministère autrichien des Affaires européennes et internationales, l’événement se veut à la fois professionnel, réflexif et convivial.

Le programme s'ouvrira à 17h30 avec une table ronde réunissant trois traducteurs issus de différentes générations du programme : Andreas Jandl, Régis Quatresous et Lionel Felchlin. Modérée par Hannah Sandvoss (France Livre), la discussion portera sur l’insertion professionnelle, les pratiques collectives de traduction et l’impact croissant de l’intelligence artificielle sur le métier.