Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

May 14, 2025 3:56 AM

|

💡Indeed the nosology of CPPD disease is out dated. The G-CAN is aiming at changing the nomenclature

👉🏼 Follow up the topic

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

July 31, 2024 9:47 AM

|

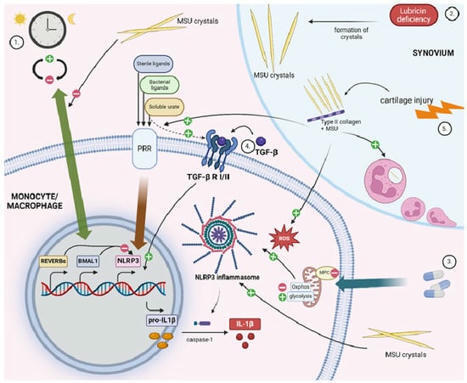

Gout is a prevalent form of inflammatory arthritis caused by the crystallization of uric acid in the joints and soft tissues, leading to acute, painful attacks. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in mononuclear cells, along with inflammasome-independent pathways, is responsible for the inflammatory phenotype in gout. Research into the different aspects of gout pathophysiology and potential treatment options is ongoing. This review highlights some of the basic research published in the 12 months following the 2022 Gout, Hyperuricemia, and Crystal-Associated Disease Network (G-CAN) conference and focuses on mechanisms of inflammation, encompassing pro- and anti-inflammatory pathways, as well as the exploration of various biological systems, such as single-cell transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and microbiome analyses.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

December 9, 2023 3:04 AM

|

📣 Editorial: Calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition disease—what's new?

✒ Author: Jürgen Braun

🔎 Read the full article: https://lnkd.in/gEz6euBM

🔎 PDF:…

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

October 4, 2019 2:24 PM

|

Gout is a chronic disease of monosodium urate crystal deposition, usually presenting as an acute inflammatory arthritis in response to deposited crystals. This PrimeView highlights evolving approaches to management of gout.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

November 17, 2018 5:09 AM

|

Abstract Objective To estimate the prevalence and distribution of asymptomatic monosodium urate monohydrate (MSU) crystal deposition in sons of patients with gout. Methods Patients with gout were mailed an explanatory letter with an enclosed postage‐paid study packet to mail to their son(s) age ≥20 years old. Sons interested in participating returned a reply form and underwent telephone screening. Subsequently, they attended a study visit at which blood and urine samples were obtained and musculoskeletal ultrasonography was performed, with the sonographer blinded with regard to the subject's serum urate level. Images were assessed for double contour sign, intraarticular or intratendinous aggregates/tophi, effusion, and power Doppler signal. Logistic regression was used to examine associations. Adjusted odds ratios (ORadj) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated. Results One hundred thirty‐one sons (mean age 43.8 years, mean body mass index 27.1 kg/m2) completed assessments. The serum urate level was ≥6 mg/dl in 64.1%, and 29.8% had either a double contour sign or intraarticular aggregates/tophi in ≥1 joint. All participants with MSU deposition had involvement of 1 or both first metatarsophalangeal joints. Intratendinous aggregates were present in 21.4% and were associated with intraarticular MSU crystal deposits (ORadj 2.96 [95% CI 1.17–7.49]). No participant with a serum urate level of ≤5 mg/dl had MSU crystal deposition seen on ultrasonography, and 24.2% of those with serum urate levels between 5 and 6 mg/dl had ultrasonographic MSU deposition. MSU crystal deposition was associated with increasing serum urate levels (ORadj 1.61 [95% CI 1.10–2.36] for each increase of 1 mg/dl). Conclusion Asymptomatic sons of patients with gout frequently have hyperuricemia and MSU crystal deposits. In this study MSU crystal deposits were present in participants with serum urate levels of ≥5 mg/dl. Evaluation of subjects without a family history of gout is needed to determine whether the threshold for MSU crystal deposition is also lower in the general population. Gout is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis and results from persistent hyperuricemia that causes intra‐ and periarticular monosodium urate monohydrate (MSU) crystal deposition. It has multiple risk factors including genetic factors that act by modulating renal uric acid excretion 1. The heritability of serum urate and urinary uric acid excretion is estimated to be ~60% and 60–87%, respectively 2, while the heritability of gout is lower at 17.0% and 35.1% in Taiwanese women and men, respectively 3, and was estimated to range between 0% and 58% in a study from the US 1. As 14.5–25% of people with high serum urate levels have asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition 4-6, studies that use a symptomatic disease phenotype may underestimate the heritability of MSU crystal deposition. The prevalence of asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition in people at high genetic risk of gout, e.g., those with a parent who has gout, is not known. It has implications for screening and primary prevention of symptomatic gout and contrasts with rheumatoid arthritis, in which familial risk and prevalence of autoantibodies in first‐degree relatives are well understood. Thus, we undertook the present study to 1) examine the prevalence and distribution of asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition among sons of people with gout; 2) examine the association between serum urate, age, and asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition; and 3) explore whether parental age at gout onset is associated with asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition in sons. Patients and Methods Study design, subject recruitment, and ethics approval. This community‐based cross‐sectional study was approved by the Nottingham NHS Research Ethics Committee 2 (Rec ref: 15/EM/0316). People with self‐reported physician‐diagnosed gout who had participated in previous surveys at Academic Rheumatology, University of Nottingham and consented to future research contact were mailed a letter informing them of the present study and were asked to mail an enclosed study packet to their sons age ≥20 years. Sons of patients with primary gout who attended the rheumatology clinic at the Nottingham NHS Treatment Centre were approached in a similar manner, and the study was advertised on Facebook and once in a local newspaper. These advertisements were targeted at sons living in and around Nottingham who have a parent with gout. Sons who returned a reply form or contacted us in response to the advertisements underwent a telephone screening questionnaire to exclude those with gout 7. The screening questionnaire included questions that form part of the 8‐point chronic gout diagnosis (CGD) scale 7. The CGD scale includes current or past history of attack of acute arthritis, monoarthritis or oligoarthritis, rapid progression of pain and swelling (<24 hours), podagra, erythema, unilateral tarsitis, tophi, and hyperuricemia 7. As serum urate was not measured at the screening visit in this study, a history of hyperuricemia was substituted. Participants scoring ≤3 on the CGD were invited for the study visit. Study visit. Participants attended a study visit at which data on demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, comorbidities, and drug prescriptions were collected. Targeted musculoskeletal assessment was performed, height, weight, and blood pressure were measured, and random blood and second‐void early‐morning urine samples were collected. Serum urate and creatinine and urinary uric acid and creatinine were measured at the clinical pathology laboratories of Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust. Fractional excretion of uric acid (FEUA) was calculated as ([urinary uric acid × serum creatinine]/[serum urate × urinary creatinine]) × 100% 8. Ultrasonography was performed by a rheumatologist with 5 years of ultrasonography experience (AA), who was blinded with regard to the subject's serum urate level. The ultrasonographic examination involved assessment of both first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints, talar domes, femoral condyles, second metacarpophalangeal joints, wrist triangular fibrocartilages, and patellar and triceps tendon insertions 9. These joints and tendons were chosen as they have best sensitivity and specificity for differentiating subjects with gout from those with other arthropathies 9. Ultrasound images were scored for double contour sign, intraarticular or intratendinous tophi/aggregates, and hyperechoic deposits (present or absent, as defined by the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology group 10). Joint effusion and power Doppler signal were graded on a 0–3 scale. All ultrasonographic assessments were performed using a Toshiba Aplio machine (8–14 MHz). Images with inconclusive readings were reviewed by a second ultrasonographer with >15 years of ultrasonography experience (PC), also under blinded conditions with regard to the subject's serum urate level. For the purpose of this study, MSU crystal deposits were defined as present if there was an intraarticular double contour sign or tophi/aggregates. Hyperechoic deposits alone were not sufficient to define MSU crystal deposits. When available, data on sex of the parent with gout and age at onset of gout were extracted from databases at Academic Rheumatology, University of Nottingham. Statistical analysis. The mean ± SD and the number (%) were used to describe continuous and categorical data, respectively. Independent‐sample t‐tests and chi‐square tests were used for univariate analysis; the Kruskal‐Wallis test was used if the data were nonparametric. Logistic regression was used to examine the association between intraarticular MSU crystal deposition at any joint in an individual and 1) serum urate level, 2) FEUA, 3) age, and 4) intratendinous aggregates/tophi at any tendon. The associations were adjusted for age where required, body mass index (kg/m2), current purine‐rich alcohol consumption (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), hyperlipidemia (yes/no), diabetes (yes/no), estimated glomerular filtration rate (ml/minute), and father with gout (yes/no). Adjusted odds ratios (ORadj) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated. The individual was the unit of analysis. Statistical calculations were performed using Stata version 15. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Results One hundred thirty‐four participants were recruited into the study: 125 via postal survey (1,435 study packets sent, 249 replies received), 6 from among sons of gout patients attending Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, and 3 from advertisements. The 3 individuals recruited from advertisements did not present for ultrasonographic assessment and were excluded from further analysis. The serum urate level was ≥6 mg/dl in 64.1% of the subjects and ≥7 mg/dl in 29.0%. Demographic characteristics and comorbidities of the 131 participants are summarized in Table 1. The mean ± SD FEUA was 5.33 ± 1.87%, and FEUA was low (defined as ≤6.6%) in 78.6% of the subjects with a serum urate level of ≥6 mg/dl. Total Asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition Present (n = 39) Absent (n = 92) Age, mean ± SD years 43.80 ± 11.20 44.20 ± 8.91 43.63 ± 12.08 Age 20–29 years, no. (%) 20 (15.3) 3 17 Age 30–39 years, no. (%) 27 (20.6) 10 17 Age 40–49 years, no. (%) 40 (30.5) 15 25 Age 50–59 years, no. (%) 36 (27.5) 10 26 Age 60–69 years, no. (%) 8 (6.1) 1 7 Body mass index, mean ± SD kg/m2 27.10 ± 4.75 27.65 ± 3.99 26.85 ± 5.04 Current purine‐rich alcohol consumption, no. (%) 97 (74.1) 31 (79.5) 66 (71.7) Weekly purine‐rich alcohol intake, median (IQR) units 10 (5–20) 10 (5–20) 10 (4–20) Hypertension, no. (%) 12 (9.2)b 3 (7.7) 9 (9.8) Hyperlipidemia, no. (%) 10 (7.6)c 3 (7.7) 7 (7.6) Diabetes, no. (%) 2 (1.5)d 0 2 (2.2) eGFR, mean ± SD ml/minute 85.23 ± 7.19 85.21 ± 7.71 85.24 ± 7.00 Serum urate, mean ± SD mg/dl 6.41 ± 1.13 6.79 ± 0.96e 6.25 ± 1.16 Serum urate <5 mg/dl, no. (%) 14 (10.5) 0 14 Serum urate ≥5 and <6 mg/dl, no. (%) 33 (26.9) 8 25 Serum urate ≥6 and <7 mg/dl, no. (%) 46 (34.3) 18 28 Serum urate ≥7 and <8 mg/dl, no. (%) 27 (20.2) 8 19 Serum urate ≥8 and <9 mg/dl, no. (%) 9 (6.7) 4 5 Serum urate ≥9 mg/dl, no. (%) 2 (1.5) 1 1 FEUA, mean ± SD % 5.3 ± 1.9 5.3 ± 1.7 5.3 ± 1.9 Father with gout, no. (%) 111 (84.7) 33 (84.6) 78 (84.8) a All participants with asymptomatic monosodium urate monohydrate (MSU) crystal deposition had first metatarsophalangeal joint involvement. IQR = interquartile range; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; FEUA = fractional excretion of uric acid. b Eleven participants were prescribed antihypertensive drugs; 1 received bendroflumethiazide. c Six participants were prescribed statins. d Both participants were prescribed oral hypoglycemic drugs. e P = 0.01 versus participants without asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition. MSU crystal deposition was found in 29.8% of the subjects, with involvement of the first MTP joint (Figure 1) observed in all subjects in whom asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition was present. MSU crystal deposition was not found in any participant with a serum urate level of ≤5 mg/dl. Among the 262 first MTP joints examined, intraarticular aggregates were numerically more common than double contour sign (Table 2). Only 1 participant had a double contour sign at the ankle, and MSU crystal deposits were not present at the other joints examined. MSU crystal deposition at the first MTP joint was associated with grade ≥2 effusion at the same joint (ORadj 9.44 [95% CI 3.62–24.63], ORadj 5.44 [95% CI 1.57–18.82] for the right and left sides, respectively). The power Doppler signal was grade ≥2 in only 1 first MTP joint. Asymptomatic MSU deposition in first MTP joints Present (n = 49) Absent (n = 213) First MTP joints Double contour sign 13 (5.0) – – Tophi 27 (10.3) – – Double contour sign and tophi 9 (3.4) – – Grade ≥2 effusion 56 (21.4) 26 30 Patellar tendon Hyperechoic deposits 19 (7.3) 11 8 Unilateral 13 7 6 Bilateral 3 2 1 Triceps tendon Hyperechoic deposits 15 (5.7) 8 7 Unilateral 13 6 7 Bilateral 1 1 0 a One participant had a double contour sign at 1 ankle; triangular fibrocartilage involvement was not observed in any participant. Values are the number (%) of joints/tendons. MSU = monosodium urate monohydrate; MTP = metatarsophalangeal. Hyperechoic aggregates were present in at least 1 tendon in 28 participants (21.4%). Sixteen participants (12.2%) had patellar tendon involvement, and 14 (10.7%) had triceps tendon involvement. Of the 28 participants with hyperechoic aggregates in at least 1 tendon, 14 had asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition at 1 or both first MTP joints. The presence of MSU crystal deposition at either first MTP joint was associated with the presence of hyperechoic aggregates in at least 1 tendon (OR 3.12 [95% CI 1.31–7.42]). This association was statistically significant after adjustment for covariates (ORadj 2.96 [95% CI 1.17–7.49]). Subjects with asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition had higher serum urate levels than those without (mean difference 0.54 mg/dl [95% CI 0.12–0.96]). The prevalence of asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition at either first MTP joint increased from 0% to 24.2%, 39.1%, 29.6%, 44.4%, and 50%, respectively, in participants with serum urate levels of <5, 5–5.99, 6–6.99, 7–7.99, 8–8.99, and ≥9 mg/dl (Table 1). Other disease, demographic, and laboratory parameters were comparable between the 2 groups (Table 1). MSU crystal deposition was associated with increasing serum urate level (OR 1.50 [95% CI 1.06–2.11], ORadj 1.61 [95% CI 1.10–2.36] for each 1‐mg/dl increase in serum urate). However, there was no association between MSU crystal deposition and uric acid underexcretion status (FEUA ≤6.6%) (OR 0.71 [95% CI 0.29–1.71], ORadj 0.78 [95% CI 0.31–1.98]). Among the 117 participants with serum urate levels of ≥5 mg/dl (the cutoff value above which MSU crystal deposits were found in this study), the prevalence of asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition was 33.33%, and this increased numerically from ages in the 20s to the 40s before stabilizing (see Supplementary Table 1, on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.40572/abstract). However, the increase was not statistically significant, and participants age >40 years were not significantly more likely to have asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition than those ≤40 years of age (OR 1.32 [95% CI 0.59–2.95], ORadj 1.69 [95% CI 0.34–8.47]). There was no association between hyperuricemia and tendon hyperechoic deposits, and, in those with serum urate levels ≥5 mg/dl, there was no association between increasing age and tendon hyperechoic deposits (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3, on the Arthritis & Rheumatology web site at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.40572/abstract). Self‐reported data on age at onset of gout were available for 60 parents. The median age at onset was 53 years. On univariate analysis, there was no association between parental gout onset at or before 53 years of age and asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition (with parental gout onset after the age of 53 years as the referent) (OR 2.64 [95% CI 0.79–8.87]). However, this approached significance after adjustment for covariates (ORadj 4.14 [95% CI 0.88–19.46], P = 0.07). Discussion This study demonstrates that the sons of patients with gout have a higher prevalence of hyperuricemia 11, uric acid underexcretion 8, and asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition than observed in previous studies in which participants were preselected according to their serum urate level 4-6. The results also raise the possibility that MSU crystal deposition occurs initially in the first MTP joints and in tendons before appearing in other joints such as the ankle and the knee. However, this observation is limited by the cross‐sectional study design. It was surprising that 1 in 5 subjects with serum urate levels between 5 and 6 mg/dl had ultrasonographic features of MSU crystal deposition at the first MTP joints. This observation must be interpreted with caution as it is based on a single serum urate measurement, and it is possible that serum urate levels in these participants were higher at a previous time. However, it raises the possibility that the threshold for MSU crystal deposition in vivo may be lower than that estimated from laboratory studies. This may be due to the fact that the saturation point of urate reduces from 6.75 mg/dl at 37°C to between 4.5 and 6 mg/dl at 30–35°C, the mean temperature of the human big toe in temperate climates 12, 13. While MSU crystals were present in subjects with serum urate levels of 5–6 mg/dl, we did not find ultrasonographic evidence of MSU crystal deposition in those with levels below 5 mg/dl. This raises the possibility that the target serum urate level for treat‐to‐target urate‐lowering therapy should be <5 mg/dl, at least in individuals who continue to have gout flares despite serum urate levels between 5 and 6 mg/dl. However, further prospective studies are needed before such a strategy can be recommended. A lower‐than‐expected serum urate level in sons of patients with gout might also be explained in part by inherited tissue factors (either an increase in promoters or decrease in inhibitors) that enhance MSU crystal deposition at relatively low serum urate levels. The present findings suggest that MSU crystal deposition begins early (in the third decade of life) and becomes more prevalent with increasing age. The reduction in prevalence of MSU crystal deposition in subjects older than 60 years could be due to the sampling for this study, as people older than 60 years with MSU crystal deposits are likely to have developed gout flares, which would have excluded them from the study population. We observed intratendinous hyperechoic deposits in 35.9% of participants with MSU crystal deposits elsewhere. This is consistent with previous reports of tendon involvement in gout 14, 15. As shown in Table 2, a substantial proportion of tendon hyperechoic deposits occurred in subjects without ultrasonographic features of MSU crystal deposition in the first MTP joints. Further research, e.g., using dual‐energy computed tomography, is therefore needed to confirm the composition of these tendinous deposits before their presence can be used to imply MSU crystal deposition in the absence of a double contour sign or intraarticular tophi in other joints. Our results indicate that ultrasonographic evaluation of both first MTP joints is sufficient to identify all individuals with MSU crystal deposition. Thus, men at a high risk of gout (e.g., those with a positive family history) could undergo serum urate measurement and ultrasonography of both first MTP joints to screen for MSU crystal deposition. While ultrasonographic examination of multiple peripheral joints is time consuming, assessment of both first MTP joints takes 10–15 minutes and may make it possible for asymptomatic MSU crystal deposits to be diagnosed, in turn allowing consideration of lifestyle changes to prevent development of symptomatic gout and associated consequences. Initiation of prophylactic pharmacologic urate‐lowering treatment at this early stage would be considered controversial given the absence of symptoms and the possibility that in many people with asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition, gout flares would not develop. Such a screening strategy would require ultrasonography of 3 individuals with a serum urate level of ≥5 mg/dl to detect 1 person with asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition. However, in the absence of prospective studies evaluating the relationship between asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition and symptomatic gout, the benefit from such a strategy remains unproven. Our data also suggest that parents with younger‐onset gout are more likely to pass on the trait to their sons, although this association was not statistically significant and requires further investigation in a study with a larger sample size. There are several caveats to this study. First, the response rate was low, and it is possible that patients with severe, troublesome gout were more likely to pass on the study packets to their sons, or that sons with lifestyle risk factors were more likely to agree to participate. This raises the possibility of selection and response bias. However, the mean ± SD age at gout onset in parents of sons who participated and for whom data on the age at gout onset were available (n = 60) was 52 ± 13.65 years, and they reported a mean ± SD of 1.33 ± 2.10 gout flares in the 12‐month period preceding their original research visit. These parents also had a low comorbidity burden, with a median of 1 cardiovascular or renal comorbidity (interquartile range 1–2). Second, we did not perform joint aspiration to confirm the validity of our findings. However, in subjects with hyperuricemia, ultrasonographic changes have 100% sensitivity and 88% specificity for MSU crystal deposition, compared to joint aspiration 5. Finally, we measured serum urate only on a single occasion. In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrate that asymptomatic sons of patients with gout frequently have hyperuricemia and uric acid underexcretion, and have a high prevalence of MSU crystal deposition. This suggests that screening of such individuals and discussion of early management, involving addressing modifiable risk factors (overweight, obesity, high fructose intake, etc.) in order to reduce their risk of developing symptomatic gout, should be considered. Acknowledgments The authors would like to acknowledge the study participants and their parents. Author Contributions All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr. Abhishek had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study conception and design Abhishek, Courtney, Jones, Zhang, Doherty. Acquisition of data Abhishek, Courtney, Jenkins. Analysis and interpretation of data Abhishek, Sandoval‐Plata. Supporting Information References Notes : Drs. Abhishek and Doherty's work was supported by an investigator‐initiated departmental research grant from AstraZeneca and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. Ms Sandoval‐Plata's work was supported by a PhD scholarship from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, Mexico. Dr. Abhishek has received speaking fees from Menarini (less than $10,000) and research grants from AstraZeneca and Oxford Immunotec. Dr. Zhang has received speaking fees and/or honoraria from AstraZeneca, Grünenthal, Bioiberica, and Hisun (less than $10,000 each). Dr. Doherty has received consulting fees and/or honoraria from AstraZeneca, Grünenthal, Mallinkrodt, and Roche (less than $10,000 each) and research grants from AstraZeneca and Oxford Immunotec. 3 All participants with asymptomatic monosodium urate monohydrate (MSU) crystal deposition had first metatarsophalangeal joint involvement. IQR = interquartile range; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; FEUA = fractional excretion of uric acid. 4 Eleven participants were prescribed antihypertensive drugs; 1 received bendroflumethiazide. 5 Six participants were prescribed statins. 6 Both participants were prescribed oral hypoglycemic drugs. 7 P = 0.01 versus participants without asymptomatic MSU crystal deposition. 8 One participant had a double contour sign at 1 ankle; triangular fibrocartilage involvement was not observed in any participant. Values are the number (%) of joints/tendons. MSU = monosodium urate monohydrate; MTP = metatarsophalangeal. Citing Literature Number of times cited: 1 Xiao Chen, Zhongqiu Wang, Na Duan, Wenjing Cui, Xiaoqiang Ding and Taiyi Jin, The benchmark dose estimation of reference levels of serum urate for gout, Clinical Rheumatology, 10.1007/s10067-018-4273-1, (2018). Crossref

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

January 11, 2017 6:38 AM

|

Le 8ème Workskhop de l'ECN a ouvert a ouvert son site pour les soumissions d'abstracts. Communications orales et posters auront lieu au cours de deux

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

March 2, 2016 1:02 PM

|

Objectives

Acute gouty arthritis is caused by endogenously formed monosodium urate (MSU) crystals, which are potent activators of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

April 23, 2015 2:43 PM

|

Arthritis Res Ther. 2015 Mar 19;17(1):65. [Epub ahead of print]

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

January 22, 2015 8:47 AM

|

ECN 2015 - Paris march 5-6th 2015

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

October 29, 2013 12:26 PM

|

The 4th workshop of the European Crystal Network took place recently in Paris. Approximately 40 biomedical scientists took part in this closed meeting, whose aim was to facilitate scientific exchange and foster collaborations ...

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

August 24, 2013 3:39 AM

|

|

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

August 2, 2024 4:24 AM

|

Lancet Rheumatology has published a review of Calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD) disease - a chronic inflammatory and degenerative crystal arthropathy that increases with aging.While the inflammatory response to calcium pyrophosphate (CPP) crystals may cause an acute or chronic inflammatory arthritis, over time CPPD is associated with cartilage degradation and osteoarthritis, but its unclear which is primary or if this evolution is bidirectional. The following are highlight or excerpts from the review article by Pascart et al:

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

February 13, 2024 11:12 AM

|

IntroductionCrystal-induced arthropathies (CiAs) are common conditions caused by the deposition of crystals within articular and periarticular tissues.1 2 The three types of crystals that are mainly involved in the pathogenesis of these diseases are monosodium urate (MSU) in gout, calcium...

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

October 23, 2019 4:46 AM

|

KEY POINTS TCR-γδ tetramer identified ligand expression by flow cytometry. TCR-γδ ligands were induced on activated monocytes or T cells. Bioinformatics combined with mass spectrometry produced an overlapping list of 16 candidate ligands. Visual Abstract Abstract Lack of understanding of the nature and physiological regulation of γδ T cell ligands has considerably hampered full understanding of the function of these cells. We developed an unbiased approach to identify human γδ T cells ligands by the production of a soluble TCR-γδ (sTCR-γδ) tetramer from a synovial Vδ1 γδ T cell clone from a Lyme arthritis patient. The sTCR-γδ was used in flow cytometry to initially define the spectrum of ligand expression by both human tumor cell lines and certain human primary cells. Analysis of diverse tumor cell lines revealed high ligand expression on several of epithelial or fibroblast origin, whereas those of hematopoietic origin were largely devoid of ligand. This allowed a bioinformatics-based identification of candidate ligands using RNAseq data from each tumor line. We further observed that whereas fresh monocytes and T cells expressed low to negligible levels of TCR-γδ ligands, activation of these cells resulted in upregulation of surface ligand expression. Ligand upregulation on monocytes was partly dependent upon IL-1β. The sTCR-γδ tetramer was then used to bind candidate ligands from lysates of activated monocytes and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Surface TCR-γδ ligand was eliminated by treatment with trypsin or removal of glycosaminoglycans, and also suppressed by inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum–Golgi transport. Of particular interest was that inhibition of glycolysis also blocked TCR-γδ ligand expression. These findings demonstrate the spectrum of ligand(s) expression for human synovial Vδ1 γδ T cells as well as the physiology that regulates their expression. This article is featured in In This Issue, p.2353 Introduction Full understanding of γδ T cell biology has been handicapped by ignorance of the ligands for most TCR-γδ. γδ T cells reside at mucosal and epithelial barriers and often accumulate at sites of inflammation with autoimmunity, infections, or tumors (1). Evidence suggests that γδ T cells provide protection against infections with bacteria, viruses, and protozoans and are generally beneficial in autoimmunity (1–17). In addition, a role for γδ T cells in the immune response against tumors in humans is evident from a seminal study reporting that intratumoral γδ T cells are the most favorable prognostic immune population across 39 cancer types in humans (18). γδ T cells are often highly lytic against transformed proliferative cells, infected cells, and infiltrating CD4+ T cells in inflammatory arthritis (9, 17, 19). They can produce a variety of cytokines including IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-17 (20), as well as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1) and keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) that promote epithelial wound repair (21). These collective studies indicate that a principal function of γδ T cells is in response to tissue injury of various causes. It is, thus, not surprising that γδ T cells are often suggested to react to host components that are upregulated or exposed during proliferation or cell injury (22). As such, γδ T cells may function in tissue homeostasis and immunoregulation as much as in protection from infection. Yet in the vast majority of cases, little if anything is known regarding the nature of these self-components or whether they actually engage the TCR-γδ. Whereas αβ T cells recognize proteins that are processed into peptides and presented on MHC molecules, the few proposed ligands for γδ T cells suggest that they recognize mostly intact proteins directly, without MHC restriction. This makes them highly attractive for immunotherapy. Despite the elaborate mechanisms that αβ T cells and B cells use to prevent autoreactivity, γδ T cells have been frequently reported to respond to autologous proteins. Furthermore, in contrast to other lymphocytes that maximize the potential diversity of their receptors, γδ T cells frequently show limitations in their diversity. Thus, human γδ T cells comprise a subset of Vδ2 T cells, the predominant γδ in peripheral blood that respond to prenyl phosphates and certain alkyl amines (23–25), and Vδ1 T cells, which do not respond to these compounds and often accumulate at epithelial barriers and sites of inflammation (1). A similar limited repertoire occurs in the mouse in which Vγ5Vδ1 cells colonize the epidermis, and a Vγ6Vδ1 subset colonizes the tongue, lung, and female reproductive tract (21, 26). This restricted repertoire implies that TCR-γδ ligands may also be limited. This may provide for a more rapid response and perhaps explain why, in contrast to αβ T cells and B cells, it is difficult to generate Ag-specific γδ T cells by immunization with a defined Ag. Various ligands for γδ T cells have been proposed, although only a few have been confirmed to bind to TCR-γδ, and these lack any obvious similarity in structure. γδ T cells for which ligands have been identified include the murine γδ T cell clone G8, which recognizes the MHC class I–like molecules T10 and T22 (27), γδ T cells from mice infected with HSV that recognize herpes glycoprotein gl (28), a subset of murine and human γδ T cells that bind the algae protein PE (20), a human γδ T cell clone G115 that recognizes ATP synthase complexed with ApoA-1 (28), a human γδ T cell clone (Vγ4Vδ5) from a CMV-infected transplant patient that recognizes endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) (29), and some human Vδ1 T cells that recognize CD1d-sulfatide Ags (30). However, to date no systematic process has been reported for determining the spectrum of human TCR-γδ ligands. To provide an unbiased approach for the identification of candidate ligands for human γδ T cells, we produced a biotinylatable form of a soluble TCR-γδ (sTCR-γδ) from a synovial Vδ1 γδ T cell clone of a Lyme arthritis patient. The tetramerized sTCR-γδ was used in flow cytometry to identify various cell types that expressed candidate ligands. Initial analysis of 24 tumor cell lines identified a set of nine ligand-positive tumors, enriched for those of epithelial and fibroblast origin, and 15 ligand-negative tumors, largely of hematopoietic origin. In addition, ligand was not expressed by primary monocytes or T cells, although each could be induced to express ligand following their activation. Ligand expression was sensitive to trypsin digestion, revealing the protein nature of the ligands, and was also reduced by inhibition of glycolysis. These findings provide a framework and strategy for the identification of individual ligands for human synovial γδ T cells. Materials and Methods Production of a sTCR-γδ Human synovial γδ T cell clones from a Lyme arthritis patient were produced as previously described (9, 31). One of these clones, Bb15, was chosen for production of the sTCR-γδ using modification of a previously reported procedure (32, 33). Both TCR chains were produced as a single transcript in a baculovirus vector. The pBACp10pH vector used contains two back-to-back promoters, p10 and polyhedrin (Fig. 1A). The p10 promoter is followed by multiple cloning sites for the γ-chain, and the polyhedrin promoter is followed by multiple cloning sites for the δ-chain. Downstream of the γ-chain, we placed a hexa-His tag for nickel column purification, followed by a biotinylation sequence for tetramerization. The γ-chain and δ-chain were PCR amplified using high fidelity polymerase (Deep Vent Polymerase; New England Biolabs). Both TCR chain sequences were verified following the initial PCR amplification as well as after insertion into the pBACp10pH vector. Virus encoding the sTCR-γδ was generated by cotransfection of Sf21 moth cells using the Sapphire baculovirus DNA and Transfection kit (Orbigen) with the sTCR pBACp10pH construct. Virus was harvested 6 d later and used as primary stocks (P1 stock). Two additional rounds of viral amplification, P2 and P3, were completed using midlog phase Sf21 cells (∼1.6 × 106 cells/ml) allowed to adhere for 1 h before infecting at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01 or 0.1 with P1 and P2 stock, respectively. After 72 h of infection, culture medium was clarified by centrifugation (1000 × g for 10 min) and filtration (VacuCap 90PF 0.8/0.2 μm Supor membrane filter units; Pall, Westborough, MA) before storing in the dark at 4°C until use. Protein production occurred in 12-l batches of midlog phase (∼1.6 × 106 cells/ml) Hi5 cells growing in suspension (0.5 l of culture in 1 l spinner flasks) and infected with P3 stock at a 1:50 dilution. Following 72 h of infection, cells were removed by centrifugation and filtration as described above. The filtered supernatant (∼12 l) containing secreted sTCR-γδ was concentrated to ∼100 ml before dialyzing against 1 l of nickel column loading buffer (20 mM NaPhosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 20 mM imidazole, 0.5 M NaCl) using a Pellicon diafiltration system with two 10K MWCO membranes (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA) back down to ∼100 ml. After system flushing, the final sample volume was ∼200 ml. It was then loaded onto loading buffer–equilibrated His-Trap HP columns (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, U.K.) at 100 ml per 2 × 5 ml columns. Columns were washed with at least 10 column volumes of loading buffer until baseline absorption was achieved. Bound proteins were eluted using a gradient from 20 to 500 mM imidiazole over 20 column volumes. Elution was monitored by absorbance at 280 nM, and 1 ml fractions were collected. Fractions containing the target protein were identified using SDS-PAGE gel analysis using Coomassie Blue. High purity (>95%) sTCR-γδ fractions were pooled, dialyzed against PBS (pH 7.4), and frozen at −80°C until used in future studies. Yields were typically ∼1.0–2.5 mg/l of culture. Purified sTCR-γδ was then biotinylated using a biotin-protein ligase system (Avidity) and tetramerized with streptavidin-PE (BioLegend) for FACS staining. Verification of TCR-γδ protein was confirmed by SDS-PAGE gel analysis using Coomassie Blue as well as immunoblot using Abs to Vδ1 or Cγ (Endogen). Flow cytometry Cells were stained with either sTCR-γδ-PE (10 μg/ml) or negative controls that included streptavidin-PE (10 μg/ml), IgG-PE (10 μg/ml) (BioLegend), or a sTCRαβ-PE (a kind gift of Dr. M. Davis). Additional surface staining of T cells consisted of CD4, CD8, CD19, and CD25 (BioLegend). Live–Dead staining (BD Bioscience) was used to eliminate dead cells from analysis. Samples were run on an LSRII flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Purification and activation of human monocytes and T cells and cell lines Human monocytes were purified from human PBMC using CD14-labeled magnetic beads, followed by column purification (Miltenyi Biotec) and then cultured in RPMI complete medium with 10% FCS in the absence or presence of either a Borrelia burgdorferi sonicate (10 μg/ml) or LPS (1 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 18 h. To some cultures were added TNF-α (10 ng/ml) (BioLegend), anti-TNF-α (10 μg/ml) (BioLegend), IL-1β (10 pg/ml) (Invitrogen), or anti–IL-1β (5 μg/ml) (R&D Systems). Cells were then stained with the sTCR-γδ tetramer. T cells from PBMC were either used fresh or were activated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 (each 10 μg/ml; BioLegend) + IL-2 (50 U/ml; Cetus) and propagated for 3 d. Cells were then stained with the sTCR-γδ tetramer. Human PBMC were obtained using an approved protocol from The University of Vermont Human Studies Committee. Verified cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. CHO cells deficient for glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) were derived as previously described (34). Bioinformatics analysis Expression profiling (35) based on Illumina RNAseq technology (36) was used to characterize the transcriptomes of 22 of the 24 tumor cell lines examined (excluding bronchoepithelial cell line and 2fTGH). Expression data for all known genes (37) were generated, and those genes whose representation in tetramer-positive cell lines was significantly higher than in negative cell lines were considered as candidate ligands. Mass spectrometry analysis Biotinylated sTCR-γδ was bound to avidin magnetic beads and then incubated with cell lysates from monocytes activated with B. burgdorferi sonicate. Magnetic beads alone, without TCR-γδ tetramer, with monocyte lysates served as a negative control. After 4 h, beads were washed five times, and bound proteins were then separated on polyacrylamide gels. Gel lanes for each sample type were cut into 12 identical regions and diced into 1-mm cubes. In-gel tryptic digestion was conducted on each region as previously described (38). Extracted peptides were subjected to liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (38), except that the analysis was performed using an LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Tandem mass spectra were searched against the forward and reverse concatenated human IPI database using SEQUEST, requiring fully tryptic peptides, allowing a mass tolerance of 2 Da and mass additions of 16 Da for the oxidation of methionine and 71 Da for the addition of acrylamide to cysteine. SEQUEST matches in the first position were then filtered by XCorr scores of 1.8, 2, and 2.7 for singly, doubly, and triply charged ions, respectively. Protein matches made with more than two unique peptides were further considered. This list had a peptide false discovery rate of <0.01%. Inhibition of glycolysis, transcription, translation, and endoplasmic reticulum–Golgi transport or trypsin or heparinases I–III treatment Inhibition of glycolysis was performed using the 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG, 5 mM; Sigma-Aldrich) for 48 h. Transcription and translation were inhibited using, respectively, actinomycin D (5 μg/ml; ICN Biomedicals) or cycloheximide (1 μg/ml; MilliporeSigma) for 18 h. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–Golgi transport was blocked using brefeldin A (1:1000) or monensin (1:1400) (BD Bioscience) for 18 h. Cell surface protein digestion was performed using trypsin (Invitrogen) (1×; 5–10 min, 37°C.). GAGs were removed from cells by treatment with heparinases I–III (2 μU/ml) for 30 min in RPMI 1640 with no serum. The reaction was then stopped by the addition of PBS–BSA. Statistical analysis The following statistical tests were used: unpaired Student t test when comparing two conditions, and one-way ANOVA with Sidak test for correction for multiple comparisons when comparing multiple variables across multiple conditions. Results Production of a human synovial sTCR-γδ We previously produced a panel of synovial Vδ1 γδ T cells from Lyme arthritis patients (9, 31). A representative clone, Bb15 (Vδ1Vγ9), was selected from which to clone its TCR-γδ. The pBACp10pH vector has been used previously to produce murine sTCR-γδ tetramers (33). It contains two back-to-back promoters, p10 and polyhedrin, in which the p10 promoter is followed by multiple cloning sites for inserting the γ-chain, and the polyhedrin promoter is followed by multiple cloning sites for inserting the δ-chain (Fig. 1A). Downstream of the γ-chain we placed a hexa-His tag for purification, followed by a biotinylation BRP sequence for tetramerization with streptavidin-PE. Protein production was undertaken in Hi5 cells followed by purification using His-Trap HP columns. Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and those with protein of the correct size were pooled, with yields typically of 1–2 mg/l of culture. A sample sTCR-γδ preparation is shown in Fig. 1B, stained with Coomassie Blue, showing bands of the expected size for the heterodimer under nonreducing (59 kDa) and reducing conditions (30/28 kDa for the γ- and δ-chains, respectively). The protein was stained by immunoblot with Abs to either Vδ1 or Cγ (Fig. 1C) and also blocked anti-γδ Ab staining of the synovial γδ T cell clones (Fig. 1D). The purified sTCR-γδ was then biotinylated and tetramerized with streptavidin-PE for use by flow cytometry. As an additional measure of specificity, sTCR-γδ tetramer staining of a fibrosarcoma tumor cell line (2fTGH) could be inhibited by anti-γδ Ab but not control IgG (Fig. 1E). Finally, staining of 2fTGH cells with the sTCR-γδ tetramer was dose dependent but did not increase with increasing dose on a negative tumor line, Daudi (Fig. 1F). FIGURE 1. Production of human synovial sTCR-γδ. (A) pBACp10pH vector containing the δ-chain driven by the polyhedrin promoter and the γ-chain with hexa-His and biotinylation BRP sequences driven by the p10 promoter from γδ T cell clone Bb15 (Vγ9Vδ1). (B) Sample of nickel NTA column-purified sTCR-γδ analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing and nonreducing conditions, and stained with Coomassie Blue. (C) Immunoblot of sTCR-γδ stained with anti-Vδ1 or anti-Cγ. (D) γδ T cell clone Bb15 was stained with anti–TCR-γδ Ab in the absence or presence of competing sTCR-γδ. (E) The fibrosarcoma cell line 2fTGH was stained with the sTCR-γδ in the absence or presence of the indicated concentrations of anti-γδ Ab or control IgG. (F) Titration of sTCR-γδ staining of the positively staining tumor line 2fTGH or negatively staining line Daudi. Number inserts indicate percent positively staining cells. Findings are representative of three experiments. Expression of sTCR-γδ candidate ligand(s) varies among cell lines We initially used the sTCR-γδ tetramer to screen a panel of 24 cell lines from a variety of cell types. None of the cell lines stained with the negative controls (IgG-PE, avidin-PE, or sTCR-αβ tetramer-PE), but the sTCR-γδ tetramer gave a spectrum of staining in which nine cell lines were strongly positive and the other cell lines manifested low to undetectable surface staining (Fig. 2). Of interest was that the positive group was enriched for cell lines of epithelial and fibroblast origin, cell types known to exist where γδ T cells are often found, such as skin, intestines, and synovium. With this information, expression profiling (35) using available RNAseq was used to characterize the transcriptomes of 22 of the 24 tumor cell lines (RNAseq on the bronchoepithelial and 2fTGH were not available). Expression data for all known genes (37) were generated, and those genes whose representation in tetramer-positive cell lines was significantly higher than in negative cell lines were considered to be candidate ligands. This produced an initial list of candidate ligands for sTCR-γδ (Supplemental Table I). FIGURE 2. sTCR-γδ tetramer staining of a cell line panel. A panel of 24 diverse cell lines was stained with either sTCR-αβ or sTCR-γδ, gated on live cells, and examined by flow cytometry. Shown are examples of tumors representing either (A) positive staining or (B) negative staining with sTCR-γδ, with the complete list summarized below each example. Number inserts indicate mean fluorescence intensity of entire histogram. Findings are representative of four experiments. Candidate sTCR-γδ ligands are sensitive to trypsin and reduced by inhibition of transcription, translation, ER–Golgi transport, or removal of GAGs We treated the positively staining cell lines with trypsin and noted a complete disappearance of surface staining, as exemplified for bronchoepithelial cells in Fig. 3A. Similar results were observed with two additional tumor lines. This supports the view that the TCR-γδ ligand contains a protein component essential for recognition by the receptor. We also observed no increase in sTCR-γδ tetramer staining of cells (C1R or HeLa) expressing CD1a, b, c, or d, nor with MICA/B (data not shown). Thus, at present there is no evidence that the synovial Vδ1 TCR-γδ ligand is one of these MHC class I–like molecules, at least bound to endogenous molecules from these particular cell lines. FIGURE 3. sTCR-γδ ligand is sensitive to protease, blockers of ER–Golgi transport, translation, or transcription and contains GAGs. The human bronchoepithelial cell line was either untreated or treated with (A) trypsin for 15 min, (B) untreated or treated for 18 h with cycloheximide or actinomycin D, or (C) untreated or treated for 18 h with brefeldin A or monensin. Cells were then stained with sTCR-γδ tetramer. (D) The 2fTGH fibrosarcoma cell line, wild-type CHO cells, or GAG-deficient CHO cells were either untreated or treated with a combination of heparinases I–III for 30 min and then stained with sTCR-γδ tetramer. Number inserts indicate mean fluorescence intensity of entire histogram. Findings are representative of three experiments. We further determined that surface TCR-γδ ligand expression was reduced by inhibition of protein translation or transcription with, respectively, cycloheximide or actinomycin D (Fig. 3B). Surface ligand was also considerably reduced by inhibition of transport from the ER to Golgi using either brefeldin A or monensin (Fig. 3C). This further demonstrated the protein nature of candidate TCR-γδ ligands. Finally, we examined the extent to which GAGs contribute to ligand binding by TCR-γδ. This was tested in two ways. Initially, the ligand-positive fibrosarcoma cell line 2fTGH was either treated or not with heparinases I–III, which removes most GAGs. This considerably reduced sTCR-γδ tetramer staining (Fig. 3D). This was further supported by the observation that sTCR-γδ stained wild-type but not GAG-deficient CHO cells (Fig. 3D). sTCR-γδ ligands are expressed by activated monocytes In considering what primary cells might express ligand(s) for the sTCR-γδ, we first examined fresh monocytes, as we had observed previously that following their activation with B. burgdorferi or LPS, monocytes could activate the synovial γδ T cell clones (31). Consistent with these earlier findings, we observed that the sTCR-γδ tetramer did not stain freshly isolated human monocytes, but following 24 h activation with a sonicate of B. burgdorferi or LPS, there was a robust upregulation of sTCR-γδ tetramer staining (Fig. 4). The same cells did not stain with negative controls that included avidin-PE, IgG-PE, or a human sTCR-αβ tetramer-PE. Because activated monocytes are known to produce certain cytokines, particularly TNF-α and IL-1β, we examined the possible influence of these cytokines on ligand expression. Curiously, the low level of sTCR-γδ tetramer staining of fresh monocytes was reduced further with TNF-α, whereas ligand expression by Borrelia-activated monocytes was not affected by the further addition of TNF-α or blocking anti–TNF-α Ab (Fig. 4B). By contrast, IL-1β increased ligand expression by fresh but not activated monocytes, and blocking anti–IL-1β Ab partially inhibited ligand expression by activated monocytes (Fig. 4C). Thus, sTCR-γδ ligand expression appears to be partly regulated by certain monocyte-derived cytokines. FIGURE 4. TCR-γδ ligand is induced on human monocytes following activation. (A) Freshly isolated monocytes were either unstimulated or activated with B. burgdorferi or LPS for 18 h and then stained with the indicated reagents and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B and C) Fresh monocytes or monocytes activated with Borrelia were incubated in the presence of medium alone or TNF-α or blocking anti-TNF-α (B) or IL-1β or blocking anti–IL-1β (C). Number inserts indicate percent positively staining cells. Error bars represent SEM. Findings are representative of four experiments. Given the induction of sTCR-γδ ligand expression by activated monocytes, we prepared lysates from Borrelia-activated monocytes and then used the biotinylated sTCR-γδ complexed with avidin magnetic beads as a bait. Following incubation with the monocyte lysates, the sTCR-γδ was isolated by magnetic purification and washed five times; bound proteins were separated on polyacrylamide gels, and gel slices were subjected to trypsin digestion and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Avidin magnetic beads alone incubated with monocyte lysates served as a negative control. This analysis yielded 291 unique proteins (Supplemental Table II). When compared with the list produced by the RNAseq bioinformatics approach of the tumor lines, 16 proteins were found in common (Supplemental Table III). Of interest is that two of these, Annexin A2 and heat shock protein 70, have previously been proposed as γδ ligands (39–41). sTCR-γδ ligands are expressed by activated T cells We further analyzed freshly isolated PBL from three individuals of various ages (28–66). This consistently revealed that fresh CD8+ T cells exhibited negligible sTCR-γδ staining, whereas a subset of fresh CD4+ T cells manifested modest levels of sTCR-γδ staining (Fig. 5A). In contrast to the freshly isolated T cells, following 3 d activation with anti-CD3/CD28 + IL-2, we observed that a subset of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells now displayed high levels of sTCR-γδ staining (Fig. 5B). Both the proportion of cells expressing ligand and the density was higher on activated CD4+ T cells compared with CD8+ T cells. Given that in vitro–activated proliferating T cells express sTCR-γδ ligand, we considered that the subset of fresh CD4+ T cells expressing ligand might also represent a proliferative subset. One of the most rapidly proliferative T cell subsets in vivo is T regulatory cells (Treg) (42). Treg can be identified as a subset of fresh CD4+ T cells expressing CD25. Indeed, when we subset fresh human CD4+ T cells based on CD25 expression, sTCR-γδ tetramer staining was again observed preferentially by the CD25+ subset (Fig. 5C). FIGURE 5. sTCR-γδ tetramer stains a subset of activated human T cells and Treg. PBL were stained with Abs to CD4 and CD8 as well as with sTCR-αβ tetramer-PE or sTCR-γδ tetramer-PE either (A) freshly isolated or (B) 3 d after activation with anti-CD3/CD28 + IL-2. Number inserts indicate the percentages of T cells staining negatively or positively with sTCR-γδ tetramer, as a portion of the total CD4+ or CD8+ subsets, as well as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in some cases. Findings are representative of six experiments. (C) Freshly isolated PBL were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD25 or isotype control, and streptavidin-PE (SA-PE) or sTCR-γδ-PE. Shown are cells gated on CD4 expression. Number inserts indicate MFI of sTCR-γδ-PE staining for CD25+ and CD25− subsets. Findings are representative of two experiments. TCR-γδ ligand expression is partly dependent upon glycolysis The finding that fresh monocytes and T lymphocytes expressed low to negligible levels of sTCR-γδ ligand(s), but upregulated expression following activation, raised the possibility that this might reflect the known induction of glycolysis following activation of T cells, monocytes, or dendritic cells (43, 44) and the resultant synthetic capacity promoted by glycolysis (45). This notion is supported by the fact that ligand-expressing Treg are also highly glycolytic (42). We thus examined this question in two ways. First, we exposed activated T cells to 2-DG, an inhibitor of glycolysis. This reduced expression of both CD25 and sTCR-γδ ligand (Fig. 6A). Second, we distinguished between activated T cells on day 3 based on their expression of CD25, as this identifies cells responsive to IL-2 and are hence most glycolytic (45). As shown in Fig. 6B, CD25+ T cells expressed sTCR-γδ ligand whereas the CD25− subset was devoid of ligand expression. Of further note is that within the CD25+ subset, CD4+ T cells again expressed more ligand than CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6B). We extended this analysis to the ligand-positive tumor 2fTGH and observed that 2-DG also resulted in reduced ligand expression in these cells (Fig. 6C). FIGURE 6. TCR-γδ ligand expression parallels glycolysis. (A and B) PBL were activated with anti-CD3/CD28 + IL-2 in the absence or presence of 2-DG (5 mM). On day 3, cells were stained with Abs to CD4, CD8, CD25, and sTCR-γδ tetramer-PE. Shown in (A) are the levels of CD25 and TCR-γδ ligand without or with 2-DG. Shown in (B) is the expression of TCR-γδ ligand in CD4+ or CD8+ subsets based on surface CD25. (C) 2fTGH cells were cultured for 48 h in either regular medium or medium plus 2-DG (5 mM). Cells were then stained with TCR-αβ or TCR-γδ. Number inserts indicate mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of sTCR-γδ-PE staining. Findings are representative of three experiments. Discussion To our knowledge, the current findings provide the first unbiased characterization of the spectrum of ligand expression for human synovial Vδ1 γδ T cells. The range of ligand expression may reflect the various locations and seemingly diverse functions attributed to γδ T cells. For example, ligand induction by B. burgdorferi– or LPS-activated monocytes parallels their known ability to activate synovial γδ T cell clones (9, 31). In addition, ligand expression by fresh CD4+ but not CD8+ T cells also correlates with our previous observations that Lyme arthritis synovial γδ T cells suppress by cytolysis the expansion of synovial CD4+ but not CD8+ T cells in response to B. burgdorferi (9). Finally, defining the spectrum of tumor cell types that express TCR-Vδ1 ligands may help explain which tumors contain Vδ1 γδ T cells and impact their effectiveness as immunotherapy. The collective findings are also most consistent with the view that γδ T cells respond to self-proteins as much as or possibly more than foreign proteins. Although these results were obtained using a sTCR-γδ tetramer from a single synovial γδ T cell clone, the fact that it shares a common Vδ1 chain found on most synovial γδ T cells (9), as well as γδ T cells found in intestinal epithelium (1, 10, 21), several tumors (18), and cells expanded in PBL following certain infections such as HIV (46, 47) and CMV (29), suggests the possibility that Vδ1 γδ T cells from these other sources may share a common physiology of ligand expression. Previous studies of ligands for murine and human γδ T cells have come largely from the identification of individual molecules that activate a specific γδ T cell clone (27–30). Although this has been successful in some instances, the current study applied a broader approach of using a sTCR-γδ tetramer in an unbiased fashion to identify the spectrum of ligand expression and how they are regulated. This approach also provided two independent methods by which to identify candidate ligands. One method used RNAseq transcriptome analysis from 22 tumor cell lines to match genes increased in positively staining tumors and decreased in negatively staining tumors. The second approach used the sTCR-γδ tetramer as a bait to bind ligands from lysates of activated monocytes and then identify the bound proteins by mass spectrometry. It is of considerable intertest that among these two sets of candidate ligands were 16 in common, two of which, Annexin A2 and heat shock protein 70, have been previously proposed as ligands for γδ T cells (39–41). By contrast, surface sTCR-γδ tetramer binding was eliminated by treatment with trypsin or removal of GAGs, and also suppressed by inhibition of ER–Golgi transport, suggesting the involvement of a combination of protein and GAGs in tetramer binding. Future studies will explore through knockdown and transfection methods whether any of the candidate ligands we have identified activate the original γδ T cell clone and the extent to which GAG/glycoprotein binding may or may not be a confounder. Although the findings thus far have not determined whether there is one or several synovial Vδ1 TCR-γδ ligands, they do provide a framework for understanding the distribution and regulation of ligand expression, which is critical for better understanding of γδ T cell biology. For example, γδ T cells have been implicated in the defense against a variety of infections (2–7), which is consistent with our finding that different TLR agonists induce TCR-γδ ligand expression on monocytes. Similar studies using a murine sTCR-γδ also found ligands induced with bacterial infection (21). In addition, γδ T cells have been found to generally alleviate various autoimmune models (12–15), which may be consistent with the expression of ligand by a subset of activated CD4+ T cells. The induction of TCR-γδ ligand expression by activation of primary monocytes or T cells, as well as ligand expression by a variety of highly proliferative tumor cell lines, suggested that the metabolic state of cells may influence their ability to express TCR-γδ ligands. Activation of monocytes and T cells is known to induce a metabolic switch to glycolysis to provide the synthetic capacity for proliferation (43, 44). In addition, Treg, which are known to be glycolytic in vivo (42), spontaneously expressed ligand. Moreover, most tumors are highly glycolytic, and the inhibition of glycolysis in these cells also reduced ligand expression. Collectively, these findings suggest that some γδ T cells may function to survey and regulate highly proliferative cells. It is of some interest that the cell lines bearing high levels of TCR-γδ ligand expression were enriched for those of epithelial and fibroblast origin, because Vδ1 γδ T cells are typically found at epithelial barriers, such as skin or intestinal epithelium, as well as in inflamed synovium, which is rich in fibroblasts (48). By contrast, sTCR-γδ ligand expression was noticeably absent from most cell lines of hematopoietic origin. The spectrum of cell line staining with the human synovial sTCR-γδ also bears considerable similarity to previous results using a murine sTCR-γδ, which strongly stained epithelial and fibroblast tumors, and less well tumors of hematopoietic origin (33). These same murine sTCR-γδ also stained macrophages activated by TLR2 or TLR4 stimuli, similar to our findings with monocytes activated by Borrelia or LPS (49). Furthermore, staining of macrophages by the murine sTCR-γδ was also not affected by the absence of β2-microgloublin, suggesting little or no contribution of ligand by classical or nonclassical MHC class I molecules. This agrees with our findings that the human synovial sTCR-γδ tetramer staining was not affected by the presence or absence of CD1 or MICA/B molecules. The findings in this study were made using primary cells and tumor cell lines. Future studies will attempt to extend these results to analyses of sTCR-γδ tetramer histologic staining of primary tissues as well as tumors and inflamed synovium to determine the spectrum of TCR-γδ ligand expression at these sites. Screening primary tumors for binding of sTCR-γδ tetramer may also help identify tumors that may benefit from immunotherapy with Vδ1 γδ T cells. In addition, identifying the ligands in inflamed synovium or intestinal epithelium will provide therapeutic strategies for manipulating the function of infiltrating γδ T cells. Disclosures The authors have no financial conflicts of interest. Acknowledgments We thank Dr. Roxana del Rio-Guerra for technical assistance with flow cytometry, as well as the Harry Hood Bassett Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Facility at The University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine. We thank Drs. Mark Davis and Naresha Saligrama for providing the human soluble TCR-αβ. We also thank the Vermont Genetics Network National Institutes of Health IDeA Networks of Biomedical Research Excellence program and the Vermont Center for Immunology and Infectious Diseases National Institutes of Health Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence program for support of the mass spectrometry facility. Footnotes This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI107298, GM118228, and AI119979 (to R.C.B.), 8P20GM103449 (to B.A.B.), HL107152 (to K.B.), and by Wellcome Trust Grants 098274/Z/12/Z (to S.D.) and 206194 (to G.J.W.). The online version of this article contains supplemental material. Abbreviations used in this article: 2-DG 2-deoxyglucose ER endoplasmic reticulum GAG glycosaminoglycan sTCR-γδ soluble TCR-γδ Treg T regulatory cell. Received April 17, 2019. Accepted August 26, 2019. Copyright © 2019 The Authors This article is distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0 Unported license. References ↵Born, W., C. Cady, J. Jones-Carson, A. Mukasa, M. Lahn, R. O’Brien. 1999. Immunoregulatory functions of gamma delta T cells. Adv. Immunol. 71: 77–144.OpenUrlPubMed ↵Shi, C., B. Sahay, J. Q. Russell, K. A. Fortner, N. Hardin, T. J. Sellati, R. C. Budd. 2011. Reduced immune response to Borrelia burgdorferi in the absence of γδ T cells. Infect. Immun. 79: 3940–3946. Hiromatsu, K., Y. Yoshikai, G. Matsuzaki, S. Ohga, K. Muramori, K. Matsumoto, J. A. Bluestone, K. Nomoto. 1992. A protective role of gamma/delta T cells in primary infection with Listeria monocytogenes in mice. J. Exp. Med. 175: 49–56. Rosat, J. P., H. R. MacDonald, J. A. Louis. 1993. A role for gamma delta + T cells during experimental infection of mice with Leishmania major. J. Immunol. 150: 550–555.OpenUrlAbstract Kaufmann, S. H., C. H. Ladel. 1994. Role of T cell subsets in immunity against intracellular bacteria: experimental infections of knock-out mice with Listeria monocytogenes and Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Immunobiology 191: 509–519.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed Tsuji, M., P. Mombaerts, L. Lefrancois, R. S. Nussenzweig, F. Zavala, S. Tonegawa. 1994. Gamma delta T cells contribute to immunity against the liver stages of malaria in alpha beta T-cell-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91: 345–349. ↵Mixter, P. F., V. Camerini, B. J. Stone, V. L. Miller, M. Kronenberg. 1994. Mouse T lymphocytes that express a gamma delta T-cell antigen receptor contribute to resistance to Salmonella infection in vivo. Infect. Immun. 62: 4618–4621. Brennan, F. M., M. Londei, A. M. Jackson, T. Hercend, M. B. Brenner, R. N. Maini, M. Feldmann. 1988. T cells expressing gamma delta chain receptors in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Autoimmun. 1: 319–326.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Vincent, M. S., K. Roessner, D. Lynch, D. Wilson, S. M. Cooper, J. Tschopp, L. H. Sigal, R. C. Budd. 1996. Apoptosis of fashigh CD4+ synovial T cells by Borrelia-reactive fas-ligand(high) gamma delta T cells in lyme arthritis. J. Exp. Med. 184: 2109–2117. ↵Rust, C., Y. Kooy, S. Pena, M. L. Mearin, P. Kluin, F. Koning. 1992. Phenotypical and functional characterization of small intestinal TcR gamma delta + T cells in coeliac disease. Scand. J. Immunol. 35: 459–468.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed Balbi, B., D. R. Moller, M. Kirby, K. J. Holroyd, R. G. Crystal. 1990. Increased numbers of T lymphocytes with gamma delta-positive antigen receptors in a subgroup of individuals with pulmonary sarcoidosis. J. Clin. Invest. 85: 1353–1361.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Peterman, G. M., C. Spencer, A. I. Sperling, J. A. Bluestone. 1993. Role of gamma delta T cells in murine collagen-induced arthritis. J. Immunol. 151: 6546–6558.OpenUrlAbstract Pelegrí, C., P. Kühnlein, E. Buchner, C. B. Schmidt, A. Franch, M. Castell, T. Hünig, F. Emmrich, R. W. Kinne. 1996. Depletion of gamma/delta T cells does not prevent or ameliorate, but rather aggravates, rat adjuvant arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 39: 204–215.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed Peng, S. L., M. P. Madaio, A. C. Hayday, J. Craft. 1996. Propagation and regulation of systemic autoimmunity by gamma delta T cells. J. Immunol. 157: 5689–5698.OpenUrlAbstract ↵Mukasa, A., K. Hiromatsu, G. Matsuzaki, R. O’Brien, W. Born, K. Nomoto. 1995. Bacterial infection of the testis leading to autoaggressive immunity triggers apparently opposed responses of alpha beta and gamma delta T cells. J. Immunol. 155: 2047–2056.OpenUrlAbstract Girardi, M., D. E. Oppenheim, C. R. Steele, J. M. Lewis, E. Glusac, R. Filler, P. Hobby, B. Sutton, R. E. Tigelaar, A. C. Hayday. 2001. Regulation of cutaneous malignancy by gammadelta T cells. Science 294: 605–609. ↵Costa, G., S. Loizon, M. Guenot, I. Mocan, F. Halary, G. de Saint-Basile, V. Pitard, J. Déchanet-Merville, J. F. Moreau, M. Troye-Blomberg, et al. 2011. Control of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic cycle: γδ T cells target the red blood cell-invasive merozoites. Blood 118: 6952–6962. ↵Gentles, A. J., A. M. Newman, C. L. Liu, S. V. Bratman, W. Feng, D. Kim, V. S. Nair, Y. Xu, A. Khuong, C. D. Hoang, et al. 2015. The prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across human cancers. Nat. Med. 21: 938–945.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Wilhelm, M., V. Kunzmann, S. Eckstein, P. Reimer, F. Weissinger, T. Ruediger, H. P. Tony. 2003. Gammadelta T cells for immune therapy of patients with lymphoid malignancies. Blood 102: 200–206. ↵Zeng, X., Y.-L. Wei, J. Huang, E. W. Newell, H. Yu, B. A. Kidd, M. S. Kuhns, R. W. Waters, M. M. Davis, C. T. Weaver, Y. Chien. 2012. Gamma delta T cells recognize a microbial encoded B cell antigen to initiate a rapid antigen-specific interleukin-17 response. Immunity 37: 524–534.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Nielsen, M. M., D. A. Witherden, W. L. Havran. 2017. γδ T cells in homeostasis and host defence of epithelial barrier tissues. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17: 733–745.OpenUrlCrossRef ↵Hirsh, M. I., W. G. Junger. 2008. Roles of heat shock proteins and gamma delta T cells in inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 39: 509–513.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Morita, C. T., E. M. Beckman, J. F. Bukowski, Y. Tanaka, H. Band, B. R. Bloom, D. E. Golan, M. B. Brenner. 1995. Direct presentation of nonpeptide prenyl pyrophosphate antigens to human gamma delta T cells. Immunity 3: 495–507.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed Tanaka, Y., C. T. Morita, E. Nieves, M. B. Brenner, B. R. Bloom. 1995. Natural and synthetic non-peptide antigens recognized by human gamma delta T cells. Nature 375: 155–158.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Bukowski, J. F., C. T. Morita, M. B. Brenner. 1999. Human gamma delta T cells recognize alkylamines derived from microbes, edible plants, and tea: implications for innate immunity. Immunity 11: 57–65.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Witherden, D. A., K. Ramirez, W. L. Havran. 2014. Multiple receptor-ligand interactions direct tissue-resident γδ T cell activation. Front. Immunol. 5: 602.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Adams, E. J., Y. H. Chien, K. C. Garcia. 2005. Structure of a gammadelta T cell receptor in complex with the nonclassical MHC T22. Science 308: 227–231. ↵Chien, Y. H., Y. Konigshofer. 2007. Antigen recognition by gammadelta T cells. Immunol. Rev. 215: 46–58.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Willcox, C. R., V. Pitard, S. Netzer, L. Couzi, M. Salim, T. Silberzahn, J.-F. Moreau, A. C. Hayday, B. E. Willcox, J. Déchanet-Merville. 2012. Cytomegalovirus and tumor stress surveillance by binding of a human γδ T cell antigen receptor to endothelial protein C receptor. Nat. Immunol. 13: 872–879.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Luoma, A. M., C. D. Castro, T. Mayassi, L. A. Bembinster, L. Bai, D. Picard, B. Anderson, L. Scharf, J. E. Kung, L. V. Sibener, et al. 2013. Crystal structure of V1 T cell receptor in complex with CD1d-sulfatide shows MHC-like recognition of a self-lipid by human T cells. Immunity 39: 1032–1042.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Vincent, M. S., K. Roessner, T. Sellati, C. D. Huston, L. H. Sigal, S. M. Behar, J. D. Radolf, R. C. Budd. 1998. Lyme arthritis synovial gamma delta T cells respond to Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins and lipidated hexapeptides. J. Immunol. 161: 5762–5771. ↵Kappler, J., J. White, H. Kozono, J. Clements, P. Marrack. 1994. Binding of a soluble alpha beta T-cell receptor to superantigen/major histocompatibility complex ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91: 8462–8466. ↵Aydintug, M. K., C. L. Roark, X. Yin, J. M. Wands, W. K. Born, R. L. O’Brien. 2004. Detection of cell surface ligands for the gamma delta TCR using soluble TCRs. J. Immunol. 172: 4167–4175. ↵Esko, J. D., T. E. Stewart, W. H. Taylor. 1985. Animal cell mutants defective in glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82: 3197–3201. ↵‘t Hoen, P. A., Y. Ariyurek, H. H. Thygesen, E. Vreugdenhil, R. H. Vossen, R. X. de Menezes, J. M. Boer, G. J. van Ommen, J. T. den Dunnen. 2008. Deep sequencing-based expression analysis shows major advances in robustness, resolution and inter-lab portability over five microarray platforms. Nucleic Acids Res. 36: e141.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Bentley, D. R., S. Balasubramanian, H. P. Swerdlow, G. P. Smith, J. Milton, C. G. Brown, K. P. Hall, D. J. Evers, C. L. Barnes, H. R. Bignell, et al. 2008. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature 456: 53–59.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Hubbard, T. J., B. L. Aken, S. Ayling, B. Ballester, K. Beal, E. Bragin, S. Brent, Y. Chen, P. Clapham, L. Clarke, et al. 2009. Ensembl 2009. Nucleic Acids Res. 37: D690–D697.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Ballif, B. A., Z. Cao, D. Schwartz, K. L. Carraway III., S. P. Gygi. 2006. Identification of 14-3-3epsilon substrates from embryonic murine brain. J. Proteome Res. 5: 2372–2379.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Marlin, R., A. Pappalardo, H. Kaminski, C. R. Willcox, V. Pitard, S. Netzer, C. Khairallah, A. M. Lomenech, C. Harly, M. Bonneville, et al. 2017. Sensing of cell stress by human gammadelta TCR-dependent recognition of annexin A2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114: 3163–3168. Born, W., L. Hall, A. Dallas, J. Boymel, T. Shinnick, D. Young, P. Brennan, R. O’Brien. 1990. Recognition of a peptide antigen by heat shock–reactive gamma delta T lymphocytes. Science 249: 67–69. ↵Chen, H., X. He, Z. Wang, D. Wu, H. Zhang, C. Xu, H. He, L. Cui, D. Ba, W. He. 2008. Identification of human T cell receptor gammadelta-recognized epitopes/proteins via CDR3delta peptide-based immunobiochemical strategy. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 12528–12537. ↵Galgani, M., V. De Rosa, A. La Cava, G. Matarese. 2016. Role of metabolism in the immunobiology of regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 197: 2567–2575. ↵Kamiński, M. M., S. W. Sauer, M. Kamiński, S. Opp, T. Ruppert, P. Grigaravičius, P. Grudnik, H. J. Gröne, P. H. Krammer, K. Gülow. 2012. T cell activation is driven by an ADP-dependent glucokinase linking enhanced glycolysis with mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation. Cell Rep. 2: 1300–1315.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Everts, B., E. Amiel, S. C. Huang, A. M. Smith, C. H. Chang, W. Y. Lam, V. Redmann, T. C. Freitas, J. Blagih, G. J. van der Windt, et al. 2014. TLR-driven early glycolytic reprogramming via the kinases TBK1-IKKɛ supports the anabolic demands of dendritic cell activation. Nat. Immunol. 15: 323–332.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Vander Heiden, M. G., L. C. Cantley, C. B. Thompson. 2009. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 324: 1029–1033. ↵Li, Z., Y. Jiao, Y. Hu, L. Cui, D. Chen, H. Wu, J. Zhang, W. He. 2015. Distortion of memory Vδ2 γδ T cells contributes to immune dysfunction in chronic HIV infection. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 12: 604–614.OpenUrl ↵Li, Z., W. Li, N. Li, Y. Jiao, D. Chen, L. Cui, Y. Hu, H. Wu, W. He. 2014. γδ T cells are involved in acute HIV infection and associated with AIDS progression. PLoS One 9: e106064. ↵Firestein, G. S. 2005. Immunologic mechanisms in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 11(3 Suppl.): S39–S44.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed ↵Aydintug, M. K., C. L. Roark, J. L. Chain, W. K. Born, R. L. O’Brien. 2008. Macrophages express multiple ligands for gammadelta TCRs. Mol. Immunol. 45: 3253–3263.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

March 14, 2019 9:09 AM

|

CHICAGO—Suleman Bhana, MD, a rheumatologist at New York-based Crystal Run Healthcare, calls himself a “technology nerd,” but judging by his review of tech tools at the 2018 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, you don’t have to geek out to embrace technology in your rheumatology practice. You just have to like simplicity and saving money. You Might Also... [Read More]

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

October 8, 2018 4:21 AM

|

The deposition of calcium-containing crystals can result in various acute and chronic arthropathies. Understanding the biological effects of these crystals and underlying pathogenic mechanisms might inform on the development of future therapeutic strategies for these conditions.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

April 2, 2016 6:48 AM

|

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

July 28, 2015 5:00 AM

|

Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Jul 24. pii: annrheumdis-2015-207656. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207656. [Epub ahead of print]

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

February 7, 2015 6:46 AM

|

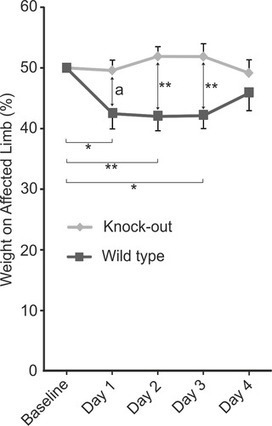

by Lauri J. Moilanen, Mari Hämäläinen, Lauri Lehtimäki, Riina M. Nieminen, Eeva Moilanen

Introduction In gout, monosodium urate (MSU) crystals deposit intra-articularly and cause painful arthritis.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

December 15, 2013 11:27 AM

|

RHUMATOLOGIE - RHEUMATOLOGY

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

October 1, 2013 1:39 PM

|

Adult with polyarthritis. (Calcium Pyrophosphate arthropathy Imaging Findings

Resembles osteoarthritis

Joint space narrowing

Extensive...

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

August 6, 2013 4:39 PM

|

Dr. Terence W. Starz discusses crystals in the muscular and skeletal system.

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...