Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 24, 10:48 AM

|

RetroVirox has launched a Summer Promotion with a 30% discount for antiviral and neutralization services against 4 viruses, including influenza, dengue, human metapneumovirus (HMPV) and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Discount applies to services initiated between July 1 and August 31 2025

Contact us at info@retrovirox.com for inquiries and additional info

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

December 20, 12:39 PM

|

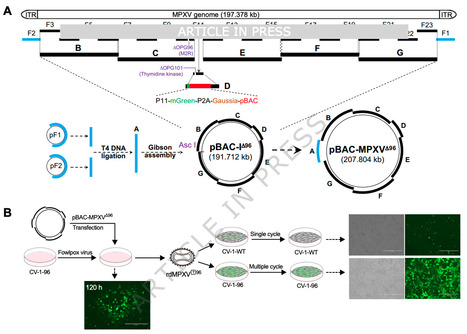

The recent global outbreaks of mpox highlight the urgent need for both fundamental research and antiviral development. However, studying the mpox virus (MPXV), with its large and complex genome, remains challenging due to the requirement for high-containment facilities. Here, we describe a strategy for de novo assembly of MPXV clade IIb genomes in bacterial artificial chromosomes using transformation-associated recombination cloning. Leveraging CRISPR-Cas9 and Lambda Red recombination, we engineer replication-defective MPXV particles with dual deletions of OPG96 (M2R) and OPG158 (A32.5 L)—genes essential for virion assembly, that are capable of recapitulating key stages of the viral life cycle. We apply this system to screen a compound library and identify G243-1720, a potent anti-poxvirus inhibitor with broad activity in vitro and in vivo. G243-1720 blocks the formation of extracellular enveloped virions and cell-cell spread. Resistance mutation selection, crystallographic analysis, analytical ultracentrifugation, and mass photometry reveal that, despite its distinct chemical structure, G243-1720 shares a mode of action with tecovirimat, both functioning by affecting dimerization of protein OPG57 (F13). Our findings underscore the potential of G243-1720 as a promising broad-spectrum anti-poxvirus lead compound and demonstrate the utility of replication-defective MPXV particles as a reliable platform for viral biology studies and antiviral development. The recent global mpox outbreaks underscore the critical need for antiviral development, hindered by the complexity of the MPXV genome. Using yeast TAR cloning, CRISPR-Cas9, and Lambda Red recombination to engineer replication-defective MPXV, the authors offer a platform for therapeutic research and identify G243-1720, a compound with a tecovirimat-like mechanism, as a promising anti-poxvirus compound. Published in Nature Communications (Dec. 15 2025): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67487-w

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

December 13, 1:42 PM

|

Oseltamivir, a neuraminidase (NA) inhibitor, is currently the most widely used antiviral drug for influenza worldwide. The emergence of primary oseltamivir-resistant mutations in NA protein of seasonally circulating viruses has been extensively monitored to evaluate drug efficacy. In addition to primary mutations in NA, mutations in the viral hemagglutinin (HA) protein have been observed to arise alongside NA mutations in previous laboratory selection experiments under neuraminidase inhibitor pressure, such HA mutations have not yet been reported in circulating viruses. Here, we present the experimental evidence that an A(H1N1)pdm09 virus can independently acquire oseltamivir-resistance mutations K130N or K130E in the HA receptor binding site (RBS) during serial passages under drug selection. Notably, HA-K130N mutation has been prevalent in currently circulating seasonal viruses worldwide since 2019. More importantly, we demonstrate that the HA-K130N can enhance the oseltamivir resistance conferred by the well-characterized NA-N295S mutation. Our study provides essential evidence that mutations in HA are closely associated with the occurrence of neuraminidase inhibitor resistance, highlighting the urgent need for global monitoring and assessment of oseltamivir-resistant mutations in the HA protein, in addition to NA, during the ongoing H1N1 epidemics. This study identifies a primary oseltamivir-resistance mutation in influenza hemagglutinin, which arises independently and enhances resistance when combined with a known neuraminidase mutation, underscoring the need for broader antiviral surveillance beyond neuraminidase. Preprint for Nature Comm. (Dec. 10, 2025) available: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66307-5

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

December 3, 10:46 AM

|

The shingles vaccine not only offers protection against the painful viral infection, but a new study suggests that the two-dose shot also may slow the progression of dementia. Shingles, caused by the varicella-zoster virus, presents as a painful rash and it’s estimated that about 1 in every 3 people in the United States will develop the illness in their lifetime. But the risk of shingles and serious complications increases with age, which is why in the United States, two doses of the shingles vaccine is recommended for adults 50 and older. Vaccination is estimated to be more than 90% effective at preventing shingles in older adults, but recent research has shed light on some other potential benefits, too. Emerging research suggests that getting the vaccine to protect against shingles may reduce the risk of developing dementia. A follow-up study, published Tuesday in the journal Cell, adds to that research by suggesting that the vaccine could also have therapeutic properties against dementia, by slowing the progression of the disease, leading to a reduced risk of dying from the disease. “We see an effect on your probability of dying from dementia among those who already have dementia,” Dr. Pascal Geldsetzer, assistant professor of medicine at Stanford University and senior author of the new study, said of the potential effects of the shingles vaccine. “That means that the vaccine doesn’t just have a preventive potential, but actually a therapeutic potential as a treatment, because we see some benefits already among those who have dementia,” he said. “To me, this was really exciting to see and unexpected.” The new study comes just months after Geldsetzer and his colleagues found evidence that shingles vaccination may offer a “dementia-preventing” or “dementia-delaying” effect. In that study, the researchers analyzed the health records of older adults in Wales, where a shingles vaccination program for adults in their 70s was introduced September 1, 2013. The program indicated that anyone who was 79 on that date was eligible for the vaccine for one year, but those who were 80 or older were not eligible for the vaccine. Those eligibility requirements allowed the researchers to examine data on the adults who were 79 and got vaccinated and then compare that data with the adults who were 80 and not eligible for vaccination but may have gotten the vaccine if they could. “We are comparing groups of patients whose only difference is a tiny difference in age, just like a week or so, and they have this massive difference in the probability of ever getting vaccinated because of these unique eligibility rules,” Geldsetzer said. Among those adults in Wales, the researchers found that receiving the shingles vaccine reduced the probability of being newly diagnosed with dementia by 3.5 percentage points over a seven-year period, compared with not receiving the vaccine. “We know they should have similar physical activity level, diets, et cetera,” Geldsetzer said. “So, we’re much more confident that what we’re actually looking at here is cause and effect, rather than just correlation.” In the new follow-up study, the researchers analyzed the same data set of the adults in Wales, which included more than 282,500 adults. But this time, the researchers examined differences in the occurrence of mild cognitive impairment diagnoses and, among people living with dementia, differences in the incidence of deaths due to dementia, while comparing vaccinated versus unvaccinated groups. “The key strength of our natural experiments is that these comparison groups should be similar in all characteristics except for a minute difference in age,” the researchers wrote. To strengthen their findings, the researchers also analyzed similar health records in Australia, which has a similar shingles vaccination program as Wales...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

November 28, 11:37 AM

|

A man in Germany is HIV-free after receiving stem cells that are not resistant to the virus. A 60-year-old man in Germany has become at least the seventh person with HIV to be announced free of the virus after receiving a stem-cell transplant But the man, who has been virus-free for close to six years, is only the second person to receive stem cells that are not resistant to the virus. “I am quite surprised that it worked,” says Ravindra Gupta, a microbiologist at the University of Cambridge, UK, who led a team that treated one of the other people who is now free of HIV. “It’s a big deal.” The first person found to be HIV-free after a bone-marrow transplant to treat blood cancer was Timothy Ray Brown, who is known as the Berlin patient. Brown and a handful of others received special donor stem cells. These carried a mutation in the gene that encodes a receptor called CCR5, which is used by most HIV virus strains to enter immune cells. To many scientists, these cases suggested that CCR5 was the best target for an HIV cure. The latest case — presented at the 25th International AIDS Conference in Munich, Germany, this week — turns that on its head. The patient, referred to as the next Berlin patient, received stem cells from a donor who only had one copy of the mutated gene, which means their cells do express CCR5, but at lower levels than usual. The case sends a clear message that finding a cure for HIV is “not all about CCR5”, says infectious-disease physician Sharon Lewin, who heads The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity in Melbourne, Australia. Ultimately, the findings widen the donor pool for stem-cell transplants, a risky procedure offered to people with leukaemia but unlikely to be rolled out for most individuals with HIV. Roughly 1% of people of European descent carry mutations in both copies of the CCR5 gene, but some 10% of people with such ancestry have one mutated copy. The case “broadens the horizon of what might be possible” for treating HIV, says Sara Weibel, a physician-scientist who studies HIV at the University of California, San Diego. Some 40 million people are living with HIV globally. Six years HIV-free The next Berlin patient was diagnosed with HIV in 2009. He developed a type of blood and bone-marrow cancer known as acute myeloid leukaemia in 2015. His doctors could not find a matching stem-cell donor who had mutations in both copies of the CCR5 gene. But they found a female donor who had one mutated copy, similar to the patient. The next Berlin patient received the stem-cell transplant in 2015. “The cancer treatment went very well,” says Christian Gaebler, a physician-scientist and immunologist at the Charité — Berlin University Medicine, who presented the work. Within a month, the patient’s bone-marrow stem cells had been replaced with the donor’s. The patient stopped taking antiretroviral drugs, which suppress HIV, in 2018. And now, almost six years later, researchers can’t find evidence of HIV replicating in the patient. Shrunken reservoir Previous attempts to transplant stem cells from donors with regular CCR5 genes have seen the virus reappear weeks to months after the people with HIV stopped taking antiretroviral therapy, in all but one person. In 2023, Asier Sáez-Cirión, an HIV researcher at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, presented data on an individual called the Geneva patient, who had been without antiretroviral therapy for 18 months. Sáez-Cirión says the person remains free of the virus, about 32 months later. Researchers are now trying to work out why these two transplants succeeded when others have failed. They propose several mechanisms. First, antiretroviral treatment causes the amount of virus in the body to drop considerably. And chemotherapy before the stem-cell transplant kills many of the host’s immune cells, which is where residual HIV lurks. Transplanted donor cells might then mark leftover host cells as foreign and destroy them, together with any virus residing in them. The rapid and complete replacement of the host’s bone-marrow stem cells with those of the donor’s might also contribute to the swift eradication. “If you can shrink the reservoir enough, you can cure people,” says Lewin. The fact that both the next Berlin patient and his stem cell donor had one CCR5 gene copy with a mutation could have created an extra barrier to the virus entering cells, says Gaebler. The case also has implications for therapies currently in early-stage clinical trials, in which the CCR5 receptor is sliced out of a person’s own cells using CRISPR–Cas9 and other gene-editing techniques, says Lewin. Even if these therapies don’t get to every single cell, they could still have an impact, she says.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

November 19, 11:22 AM

|

Resistance to antibiotics is approaching crisis levels for organisms such as the ESKAPEE pathogens (includes Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter spp., and Escherichia coli) that often are acquired in hospitals. These organisms sometimes have acquired plasmids that confer resistance to most if not all beta-lactam antibiotics. We have been developing alternative means for dealing with antibiotic resistant microbes that cause infections in humans by developing viruses (bacteriophages) that attack and kill them. One of these pathogens, K. pneumoniae, has one of the highest propensities for antimicrobial resistance. We identified many phages that have lytic capacity against limited numbers of clinical isolates, and through experimental evolution over the course of 30 days, were able to vastly expand the host ranges of these phages to kill a broader range of clinical K. pneumoniae isolates including MDR (multi-drug resistant) and XDR (extensively-drug resistant) isolates. Most interestingly, they were capable of inhibiting growth of clinical isolates both on solid and in liquid medium over extended periods. That we were able to extend the host ranges of multiple naïve antibiotic resistant K. pneumoniae through experimental phage evolution suggests that such a technique may be applicable to other antibiotic-resistant organisms to help stem the tide of antibiotic resistance and offer further options for medical treatments. Ghatbale et al. adapted a co-evolutionary technique to develop Klebsiella pneumoniae phages to be highly active longitudinally against K. pneumoniae clinical isolates, including drug resistant isolates. Published in Nat. Comm. (Nov. 19, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66062-7

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

November 15, 2:04 PM

|

Health officials say a person in the state of Washington has a new form of bird flu virus. The virus, H5N5, never has been seen in a person before. It appeared first in 2023 in birds and mammals in eastern Canada. The strain was confirmed by the Washington State Department of Health on Friday. “Given the rarity of such infections in humans and the fact that this person was hospitalized, there is an urgency to figure out how this person may have come in contact with the virus and whether anyone else was infected,” said Jennifer Nuzzo, director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University in Providence, R.I. Epidemiologists and virologists worry that avian influenzas could generate a pandemic if allowed to spread and mutate. For instance, the H5N1 virus circulating in dairy cattle in North America is one mutation away from being able spread easily between people. “Anytime someone is infected with a novel influenza virus, we want to gather as much information as we can to be sure the virus hasn’t gained the ability to more easily infect and spread between humans, which would trigger a pandemic,” Nuzzo said. The case involves a person who lives in Grays Harbor County on the Olympic Peninsula. Their illness became severe enough that they were transferred to a hospital in more populous Thurston County and then to King County, where Seattle is located. Melissa Dibble, a spokesperson for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, confirmed the Washington health department’s finding, and said the patient had a backyard flock of “mixed domestic poultry.” “The domestic poultry or wild birds are the most likely source of virus exposure,” she said in an email. According to a news release from county health officials, the person is “older” and has underlying health conditions. Their symptoms included a high fever, confusion and trouble breathing. The person has been hospitalized since early November. “The fact that the patient experienced severe illness from this infection only increases the urgency to know more about this particular case,” Nuzzo said. Henry Niman, an evolutionary molecular biologist and founder of Recombinomics Inc., a virus and vaccine research company in Pittsburgh, said other animals and birds in Canada also have been infected, including a red fox, cat and raccoon. According to research published last year on the novel strain, some infected animals carried a key mutation in the virus that allows it to transfer more easily between mammals. Every time a bird flu virus infects a person, concerns grow that it could change, becoming more transmissible or more deadly. For instance, if a sickened person also has another flu virus replicating in their body, there’s concern the viruses could exchange genetic material. Just by having an opportunity to replicate and evolve millions of times in the human body, it could acquire deadly mutations. Samples of a virus taken from a critically ill teenager in Canada, for example, showed the virus acquired genes that allowed it to target human cells more easily and cause severe disease. Richard Webby, an influenza expert at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., said the new virus is “interesting,” but he isn’t overly concerned yet. “No reason to expect an elevated risk,” he said. However, Niman, the molecular biologist, said the fact that it has presented as a severe clinical case in the first person infected with it should be cause for concern. “I think this is a big deal,” he said. Dibble, the CDC spokeswoman, said they are investigating the case with Washington’s health department and maintain that the the risk of bird flu to the general public remains low. The CDC urges caution, however, for people who work with or have recreational contact with infected birds, cattle or other potentially infected domestic or wild animals. They should wear gloves, masks and eye protection. They also recommend people (and their pets) avoid raw or undercooked meat and eggs and raw milk or cheeses.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

November 13, 11:12 AM

|

Since late 2021, a panzootic of highly pathogenic H5N1 has devastated wild birds, agriculture and mammals. Here an analysis of 1,818 haemagglutinin sequences from wild birds, domestic birds and mammals reveals that the North American panzootic was driven by around nine introductions into the Atlantic and Pacific flyways, followed by rapid dissemination through wild, migratory birds. Transmission was primarily driven by Anseriformes, while non-canonical species acted as dead-end hosts. In contrast to the epizootic of 2015 (refs. 1,2), outbreaks in domestic birds were driven by around 46–113 independent introductions from wild birds that persisted for up to 6 months. Backyard birds were infected around 9 days earlier on average than commercial poultry, suggesting potential as early-warning signals for transmission upticks. We pinpoint wild birds as critical drivers of the epizootic, implying that enhanced surveillance in wild birds and strategies that reduce transmission at the wild–agriculture interface will be key for future tracking and outbreak prevention. The panzootic of highly pathogenic H5N1 since 2021 was driven by around nine introductions into the Atlantic and Pacific flyways, followed by rapid dissemination through wild migratory birds, primarily Anseriformes. Published in Nature (Nov. 12, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09737-x

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

November 7, 11:23 AM

|

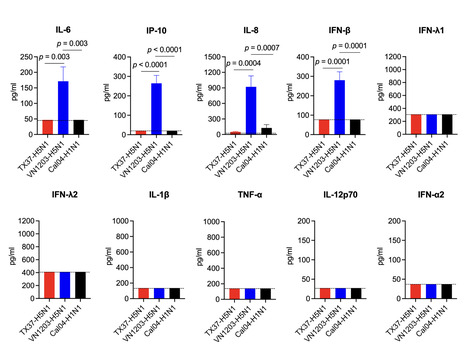

The H5N1 high pathogenicity avian influenza virus (HPAIV) of clade 2.3.4.4b, which spreads globally via wild birds, has become a major public health concern because it can infect a variety of mammals, including humans. In 2024, infection of dairy cattle with H5N1 HPAIV clade 2.3.4.4b was confirmed in the United States, and subsequent human cases were reported. Although these viruses are highly pathogenic in animal models, human infections have generally been mild, revealing a striking discrepancy. Here, we characterized the cattle-derived human H5N1 isolate A/Texas/37/2024 (TX37-H5N1) using three-dimensional human respiratory organoids derived from induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Despite efficient replication, TX37-H5N1 induced minimal interferon and inflammatory cytokine responses. Bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing revealed reduced STAT1-mediated transcriptional activity in TX37-H5N1-infected organoids compared to the historic H5N1 human isolate A/Vietnam/1203/2004. These findings suggest that TX37-H5N1 fails to trigger the strong innate responses, including robust cytokine production, that are typically associated with severe H5N1 disease and are thought to contribute to cytokine storm-medicated pathogenesis. This attenuated response may help explain the discrepancy between the high pathogenicity of TX37-H5N1 in animal models and its mild clinical presentation in humans. While zoonotic influenza risk is often assessed using cell lines or animal models, our study highlights the value of using human respiratory organoids to evaluate human-specific virus-host interactions. This platform provides a complementary tool for assessing the risk of emerging avian influenza viruses. Highlights -

Human respiratory organoids were used to model zoonotic B3.13 H5N1 infections. -

A cattle-derived human isolate, TX37-H5N1, replicated more efficiently than historical VN1203-H5N1. -

TX37-H5N1 suppressed STAT–IRF-mediated innate immune responses. -

TX37-H5N1 was sensitive to baloxavir and oseltamivir but less sensitive to favipiravir. -

Human respiratory organoids offer a complementary platform for zoonotic influenza risk assessment. In brief Our study used human iPSC-derived respiratory organoids to investigate the mild clinical presentation of zoonotic B3.13 H5N1 viruses. We found that TX37-H5N1 replicates efficiently but suppresses innate immune responses, providing mechanistic insight into species-specific pathogenesis and highlighting the utility of human organoids for zoonotic risk assessment. Preprint in bioRxiv (Nov. 2, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.11.02.684669

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

October 31, 11:53 AM

|

Children may be more likely to be diagnosed with autism and other neurodevelopment disorders if their mother had a Covid-19 infection while pregnant, according to a new study. Researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital analyzed more than 18,000 births that occurred in the Mass General Brigham health system between March 2020 and May 2021, assessing records for laboratory-confirmed Covid-19 tests among the mothers and for neurodevelopment diagnoses among their children through age 3. They found that children born to mothers who had Covid-19 during pregnancy were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with a neurodevelopment disorder than those born to mothers who did not have an infection while pregnant: more than 16% versus less than 10%, or a 1.3 times higher risk after adjusting for other risk factors. Overall, differences in risks were more pronounced among boys and in cases where the mother had a Covid-19 infection during the third trimester. Previous studies have suggested that male fetal brains are more susceptible to maternal immune responses, according to the authors of the new study, and the third trimester is a “critical window for brain development.” The most common diagnoses included disorders in speech and motor function development and autism. About 2.7% of children born to mothers who had Covid-19 while pregnant were diagnosed with autism, compared with about 1.1% of others, according to the study, published Thursday in the journal Obstetrics and Gynecology. The new findings are “particularly notable in light of their biological plausibility,” the researchers wrote. They build on previous research that identified potential pathways for a maternal Covid-19 infection to affect the developing fetal brain even without direct transmission. “Parental awareness of the potential for adverse child neurodevelopmental outcomes after COVID-19 in pregnancy is key. By understanding the risks, parents can appropriately advocate for their children to have proper evaluation and support,” Dr. Lydia Shook, maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital and lead author of the study, said in a news release. About 1 in 31 children in the US was diagnosed with autism by age 8 in 2022, according to a report published by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that was published in April. The increase — up from 1 in 36 children in 2020 — continues a long-term trend that experts have largely attributed to better understanding of and screening for the condition. Earlier this year, the US Department of Health and Human Services launched a “massive testing and research effort” to determine “what has caused the autism epidemic.” In a news conference in September on the “cause of autism,” President Donald Trump — flanked by HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and other federal health leaders – said that use of Tylenol during pregnancy can be associated with a “very increased risk of autism,” despite decades of evidence that it is safe. Kennedy also has a history of comments linking autism and vaccines, despite strong evidence that the two are not connected. The timeframe of the new study – early in the pandemic, before vaccines were widely available – meant that the researchers were able to “isolate the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and offspring neurodevelopment in an unvaccinated population.” About 93% of the mothers included in the assessment had not received any doses of Covid-19 vaccine. Strong infection-control policies at that time also helped reduce the potential for unreported or undetected Covid-19 cases, the researchers said. “These findings highlight that COVID-19, like many other infections in pregnancy, may pose risks not only to the mother, but to fetal brain development,” Dr. Andrea Edlow, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Mass General Brigham and senior author of the new study, said in a news release. “They also support the importance of trying to prevent COVID-19 infection in pregnancy and are particularly relevant when public trust in vaccines – including the COVID-19 vaccine – is being eroded.” Study published Oct. 30, 2025:

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

October 29, 10:33 AM

|

Research Highlights: - A review of 155 scientific studies found influenza and COVID infections raised the risk of heart attack or stroke as much as three-to five-fold in the weeks following the initial infection.

- Viruses that linger in the body, such as HIV, hepatitis C and varicella zoster virus (the virus that causes shingles), can lead to long-term elevations in the risk of cardiovascular events.

- The study researchers say preventive measures, including vaccination, may play an important role in reducing the risk of heart attacks and strokes, especially in people who already have heart disease or heart disease risk factors.

In the weeks following a bout of influenza or COVID, the risk of heart attack or stroke may rise dramatically, and chronic infections such as HIV may increase the long-term risk of serious cardiovascular disease events, according to new, independent research published today in the Journal of the American Heart Association, an open access, peer-reviewed journal of the American Heart Association. “It is well recognized that human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus and other viruses can cause cancer; however, the link between viral infections and other non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, is less well understood,” said Kosuke Kawai, Sc.D., lead author of the study and adjunct associate professor in the division of general internal medicine and health services research at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Our study found acute and chronic viral infections are linked to both short- and long-term risks of cardiovascular disease, including strokes and heart attacks.” The researchers set out to systematically review all published studies that investigated the association between any viral infection and the risk of stroke and heart attack, initially screening more than 52,000 publications and identifying 155 as appropriately designed and of high quality allowing for meta-analysis of the combined data. In studies that compared people’s cardiovascular risks in the weeks following documented respiratory infection vs. the same people’s risk when they did not have the infection, researchers found: - People are 4 times as likely to have a heart attack and 5 times more likely to have a stroke in the month after laboratory-confirmed influenza.

- People are 3 times more likely to have a heart attack and 3 times as likely to have a stroke in the 14 weeks following COVID infection, with the risk remaining elevated for a year.

The immune system’s natural response to viral infections includes the release of molecules that trigger and sustain inflammation and promote the tendency of blood to clot, both of which may last long after the initial infection has been resolved. Both inflammation and blood clotting can reduce the ability of the heart to function properly and may help explain the increased heart attack and stroke risk. Inflammation plays a key role in the development and progression of cardiovascular disease (CVD). It contributes to the formation and rupture of plaques in arteries, which can lead to heart attacks and strokes. Some elevated inflammatory markers are linked to worse outcomes and higher risk of future events; thus, managing inflammation is becoming an important part of preventing and treating CVD. In studies comparing long-term risk (average of more than 5 years) of cardiovascular events in people with certain chronic viral infections vs. similar people without the infection, the researchers found: - A 60% higher risk of heart attack and 45% higher risk of stroke in people with HIV infection.

- A 27% higher risk of heart attack and 23% higher risk of stroke in people with hepatitis C infection.

- A 12% higher risk of heart attack and 18% higher risk of stroke in people had shingles.

“The elevated risks for cardiovascular disease risks are lower for HIV, hepatitis C and herpes zoster than the heightened short-term risk following influenza and COVID. However, the risks associated with those three viruses are still clinically relevant, especially because they persist for a long period of time. Moreover, shingles affects about one in three people in their lifetime,” Kawai said. “Therefore, the elevated risk associated with that virus translates into a large number of excess cases of cardiovascular disease at the population level.” The findings also suggest that increased vaccination rates for influenza, COVID and shingles have the potential to reduce the overall rate of heart attacks and strokes. As an example, the researchers cite a 2022 review of available science that found a 34% lower risk of major cardiovascular events among participants receiving a flu shot in randomized clinical trials vs. participants in the same trials who were randomly selected to receive a placebo instead. “Preventive measures against viral infections, including vaccination, may play an important role in decreasing the risk of cardiovascular disease. Prevention is especially important for adults who already have cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular disease risk factors,” Kawai said. According to the American Heart Association, people may be at greater risk for cardiovascular disease because of viruses such as influenza, COVID, RSV and shingles. Additionally, because people with cardiovascular disease may face more severe complications from these viruses, the Association recommends those individuals consult with a health care professional to discuss which vaccines are right for them, as vaccination offers critical protection to people already at increased risk. Although a connection has been suggested in previous studies, researchers note there is currently limited evidence and more studies are needed to understand the possible links between heart disease risk and several other viruses, including cytomegalovirus (virus that can cause birth defects), herpes simplex 1 (virus that causes cold sores), dengue (mosquito-spread virus that can cause dengue fever) and human papilloma virus (can cause cervical and other cancers later in life).

The current analysis has some limitations as it was based on observational studies rather than randomized controlled trials; however, many of the studies accounted adequately for potential confounding factors. Because most studies examined infection with a single virus, it is unclear how infection with multiple viruses or bacteria may have affected the results. The analysis focused on viral infections that impact the general public and did not identify high-risk groups (such as transplant recipients) that may be disproportionately affected. Study details, background and design: - Investigators searched multiple medical databases from inception through July 2024 for studies examining the association of viral infections and cardiovascular diseases, then screened 52,336 possibly relevant publications and selected 155 studies as appropriate for analysis.

- Studies were published between 1997 and 2024 and most were conducted in North America (67), Europe (46) and East Asia (32).

- 137 studies evaluated one viral infection and 18 studies evaluated 2 or more.

- For each virus under consideration, researchers performed a meta-analysis of studies employing the same study design.

Co-authors, disclosures and funding sources are listed in the manuscript. Studies published in the American Heart Association’s scientific journals are peer-reviewed. The statements and conclusions in each manuscript are solely those of the study authors and do not necessarily reflect the Association’s policy or position. The Association makes no representation or guarantee as to their accuracy or reliability. The Association receives more than 85% of its revenue from sources other than corporations. These sources include contributions from individuals, foundations and estates, as well as investment earnings and revenue from the sale of our educational materials. Corporations (including pharmaceutical, device manufacturers and other companies) also make donations to the Association. The Association has strict policies to prevent any donations from influencing its science content and policy positions. Overall financial information is available here.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

October 25, 11:12 AM

|

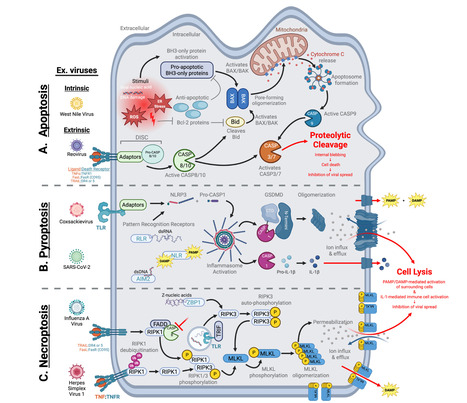

Mammalian cells employ a wide array of antiviral defense mechanisms to restrict viral replication at virtually all steps of the viral life cycle. Notably, the interferon (IFN) response has been shown to play a central role in restricting the replication of disparate viral pathogens in mammals. Consequently, since its discovery in 1957, the IFN response has dominated antiviral immunity research, leaving IFN-independent pathways relatively understudied. Exploring these alternative host defenses is crucial for understanding the complete arsenal that mammalian hosts deploy to combat viral disease, as IFN responses undoubtedly work in concert with other antiviral defenses to achieve virus restriction. Here, we discuss selected examples of antiviral factors and pathways in mammals that are not classically associated with the IFN response. These defenses range from constitutively expressed host restriction factors that directly inhibit specific steps of the viral life cycle to signaling pathways that invoke IFN-independent antiviral gene expression programs to cell death mechanisms that sacrifice the infected cell to prevent viral spread. Ultimately, our goal is to highlight the diversity of IFN-independent antiviral defenses that mammalian hosts utilize to block viral infection. Published in J. Virology (Oct. 2025):

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

October 23, 12:33 PM

|

mRNA vaccines seem to boost the effectiveness of an immune therapy for skin and lung cancer ― in an unexpected way. A vaccine that helps to fight cancer might already exist. People being treated for certain deadly cancers lived longer if they had received an mRNA-based vaccine against COVID-19 than if they hadn’t, finds an analysis of medical records. Follow-up experiments in mice show that the vaccines have this apparent life-extending effect not because they protect against COVID-19 but because they rev up the body’s immune system1. That response increases the effectiveness of therapies called checkpoint inhibitors, the animal data suggest. “The COVID-19 mRNA vaccine acts like a siren and activates the immune system throughout the entire body”, including inside the tumour, where it “starts programming a response to kill the cancer”, says Adam Grippin, a radiation oncologist at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, an co-author of the report published today in Nature. “We were amazed at the results in our patients.” The findings, which Grippin and his colleagues hope to validate in a clinical trial, suggest further hidden capabilities of mRNA vaccines, even as the administration of US President Donald Trump has slashed about US$500 million in funding for research investigating the technology. The US Department of Health and Human Services, which cancelled the funding for mRNA research, did not respond to a request for comment. Working in tandem Checkpoint inhibitors unleash the immune system to attack cancer cells. They have transformed the treatment of many cancers, but they fail in more than half of the people who receive them: some recipients’ immune systems remain too sluggish to attack cancer cells. To address this gap, researchers have been developing personalized ‘cancer vaccines’. These would be used in tandem with checkpoint inhibitors to help an individual’s immune system to target the unique mutations found in their cancer cells. Although early results are promising, these treatments are still experimental and, once available, will probably be very expensive and difficult to access. Grippin and his colleagues wondered whether the general immune boost that mRNA vaccines create could be enough to wake up the immune system. They found support for this theory in mice2, leading them to investigate whether the effect would carry over into people. The researchers analysed the medical records of more than 1,000 people with lung cancer or melanoma. They found that, in people with a certain type of lung cancer, receiving an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine was linked to a near doubling in survival time, from 21 months to 37 months. Unvaccinated people with metastatic melanoma survived an average of 27 months; by the time data collection ended, vaccinated people had survived so long that the researchers couldn’t calculate an average survival time. People whose tumours had traits hinting that they were unlikely to respond to checkpoint inhibitors saw the biggest survival boost after vaccination. This finding is “quite impressive”, says Benoit Van den Eynde, a tumour immunologist at the University of Oxford, UK. “I did not expect the effect to be that significant, and the data are very strong.” Window of opportunity Timing matters: those who had received the jab within 100 days of starting treatment were more likely to benefit than were those who received it outside that window. Grippin has collected data, which are yet to be published, suggesting that receiving the vaccine within a 30-day window before or after treatment could elicit an even stronger boost, he says. This survival benefit was not seen with vaccines that do not use mRNA technology, such as those for influenza and pneumonia, or in people who received a different type of cancer therapy. The follow-up experiments in mice hinted at an explanation for this increase in survival. mRNA vaccines comprise mRNA encased in fatty nanoparticles, which deliver their payload directly into cells. The combination of the fatty particles and the insertion into cells leads to potent activation of the immune system. Vaccination leads to the activation of a cascade of immune cells, which trains the body’s ‘killer’ cells to hunt for tumour cells. These killer cells are then aided by the checkpoint-inhibitor drugs, the researchers found. Maligned technology These data suggest that a measure that is both widely available — billions of doses of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine have been distributed globally — and also low-cost could help to boost survival in people with a wide array of cancers, Van den Eynde says. That doesn’t mean researchers should throw away years of investment and research into personalized cancer vaccines, Grippin says. If this approach is shown to be effective in clinical trials, Grippin says that two types of vaccine could be used simultaneously — one to stimulate a general immune response and another to train the immune system to fight cancer cells specifically. But more data would require research in a field that has been defunded and criticized by Trump-administration officials. “The current climate impacts patients because even the word, ‘mRNA’, has stigma these days,” says study co-author Steven Lin, an oncologist at MD Anderson. “We’re walking on eggshells because there’s so much negative publicity about mRNA.”

|

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

Today, 11:20 AM

|

Whale breath collected by drones is giving clues to the health of wild humpbacks and other whales. Scientists flew drones equipped with special kit through the exhaled droplets, or "blows", made when the giants come up to breathe through their blowholes. They detected a highly infectious virus linked to mass strandings of whales and dolphins worldwide. The sampling of whale "blow" is a "game-changer" for the health and well-being of whales, said Prof Terry Dawson of King's College London. "It allows us to monitor pathogens in live whales without stress or harm, providing critical insights into diseases in rapidly changing Arctic ecosystems," he said. The researchers used drones carrying sterile petri dishes to capture droplets from the exhaled breath of humpback, fin and sperm whales, combined with skin biopsies taken from boats. They confirmed for the first time that a potentially deadly whale virus, known as cetacean morbillivirus, is circulating above the Arctic Circle. The disease is highly contagious and spreads easily among dolphins, whales, and porpoises causing severe disease and mass deaths. It can jump between species and travel across oceans, posing a significant threat to marine mammals. The researchers hope this breakthrough will help spot deadly threats to ocean life early, before they start to spread. "Going forward, the priority is to continue using these methods for long-term surveillance, so we can understand how multiple emerging stressors will shape whale health in the coming years," said Helena Costa of Nord University, Norway. The study, involving King's College London and The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies in the UK, and Nord University in Norway is published in BMC Veterinary Research.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

December 17, 11:46 AM

|

Scientists are deploying an array of technologies that are making a vaccine against all varieties of influenza seem more achievable. In February 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) tried to predict which strains of influenza were going to pose the biggest threat in that year’s Northern Hemisphere flu season. It failed. On the basis of surveillance data on which strains were circulating, the WHO selected four that would become the foundation of that year’s vaccine. One was an H3N2 virus strain that was the most prevalent of that particular subtype, at that moment. But by the time the vaccine was making its way into people’s arms that autumn, a different version of the virus had taken over — and the vaccine was only 6% effective at protecting against it. That year’s Northern Hemisphere flu season was more severe than the five that had preceded it, and lasted weeks longer than any in the previous decade.This problem of antigenic drift — when gene mutations cause components of the influenza virus to change, and it evolves away from the vaccines designed to keep it in check — could be reduced by the development of a universal flu vaccine. A shot that provides broad coverage against a wide array of strains could improve efficacy significantly from the 40–60% reduction in risk that flu vaccines typically achieve. It would also eliminate the need for WHO’s twice-yearly meetings to predict which viral strains to guard against, the subsequent scramble to manufacture the vaccine and the need for people to be vaccinated year after year. Some strategies to improve the effectiveness of the flu vaccine and reduce the need for annual shots have made it into early clinical trials. A major thrust of these efforts is to coax the immune system to respond to a part of the flu virus that it normally pays little attention to. Ordinarily, the immune system produces antibodies that focus on a particular part of haemagglutinin, a protein on the surface of the virus that allows it to enter cells. Antibodies clamp to haemagglutinin and block the virus from attaching. Haemagglutinin has 18 subtypes: H1 to H18. And, unfortunately, haemagglutinin can evolve rapidly, changing its shape so that antibodies can no longer bind to it. “What we’re trying to do is trick the immune system into attacking a part of the influenza virus that it typically doesn’t attack,” says Florian Krammer, a vaccinologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Haemagglutinin is a stalk, rising from the virus surface, topped by a ball-shaped head. The immune system focuses most of its efforts here. “The head domain sticks out of the virus, so it’s very easy for B-cell receptors, which in the end become antibodies, to recognize that part,” Krammer says. “The stalk is a little bit more hidden.” Krammer treats this as a challenge, and is trying to amplify the immune response to the haemagglutinin stalk. A second protein called neuraminidase, which helps the virus spread to other cells, has 11 subtypes. Although viruses with any combination of these haemagglutinin and neuraminidase subtypes can infect people, the two currently circulating in humans are H1N1 and H3N2. Krammer and his colleagues create new versions of the virus by taking H1 stalks and replacing the heads with those from other subtypes, such as H14 or H8. Apart from newborn babies, most people have been either infected with or vaccinated against flu — or both — and so have a pre-existing immune response. When presented with a chimaera protein (say, an H1 stalk and an H8 head) the immune system recognizes the part it has seen before (the stalk)and reacts to that. “That weakens the response to the head and strengthens the response to this stalk,” Krammer says. And a stronger reaction to the stalk should, in turn, make it harder for the virus to evade the immune response. The stalk plays a crucial part in allowing the virus to fuse with the host cell, and undergoes a series of structural changes during fusion. Any mutation that interferes with those changes renders the virus ineffective, meaning the stalk can’t evolve in response to the immune system as readily as the head can. The stalk also doesn’t vary much between virus strains, so immunity against this part provides broader protection. In 2020, Krammer and his colleagues tested a vaccine in a small phase I clinical trial3. They showed that it induced a large number of antibodies to target an H1 stalk. Although the COVID-19 pandemic put the work on hold, it has since resumed. The next step will be to try the same with an H3 stalk, and to combine the two to see whether the result generates a broad antiviral response. “It’s going slowly, but it’s going,” Krammer says. At Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, microbiologist Nicholas Heaton is also trying to get the immune system to look beyond the haemagglutinin head. His aim is to get it to notice other sites on the virus at which antibodies can bind, known as epitopes. “Normally, the immune system would focus on that haemagglutinin head domain. It’s obsessed with it,” Heaton says. “If you remove it, then you say, out of everything that’s left, what do you like? And so you get these responses to other epitopes.” Heaton and his colleagues used gene editing to create more than 80,000 variations of haemagglutinin with different changes to a specific part of the head domain, but with the same stalk4. The variety of head-domain epitopes meant that the immune system focused its attention on the stalk, leading to a significant increase in stalk antibodies when tested in ferrets and mice. But Heaton didn’t want to create a new immune response at the expense of the old one. He, therefore, also used conventional methods to create a virus particle that elicited the typical haemagglutinin-head-focused response, and then mixed the two types to achieve broader immunity. The variant epitopes also seem to induce some immunity, and many might help to inhibit the virus. The stalk-binding antibodies don’t actually neutralize the virus, Heaton says, but they can help the immune system to recognize it and clear it faster, theoretically lowering the viral burden and thus the severity of the infection. “People who would have stayed out of work for two days won’t even feel sick,” Heaton says. People who might have died could instead experience just a few days of illness. “Those are the types of shifts that we think would be accomplished by lower peak viral burden and faster clearance of the virus.”.....

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

December 11, 11:15 AM

|

A new study implicates a pair of substances secreted by immune cells in inducing myocarditis among mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine recipients — and proposes a strategy to mitigate this effect. Stanford Medicine investigators have unearthed the biological process by which mRNA-based vaccines for COVID-19 can cause heart damage in some young men and adolescents — and they’ve shown a possible route to reducing its likelihood. Using advanced but now common lab technologies, along with published data from vaccinated individuals, the researchers identified a two-step sequence in which these vaccines activate a certain type of immune cell, in turn riling up another type of immune cell. The resulting inflammatory activity directly injures heart muscle cells, while triggering further inflammatory damage. The mRNA vaccines for COVID-19, which have now been administered several billion times, have been heavily scrutinized for safety and have been shown to be extremely safe, said Joseph Wu, MD, PhD, the director of the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute. “The mRNA vaccines have done a tremendous job mitigating the COVID pandemic,” said Wu, the Simon H. Stertzer, MD, Professor and a professor of medicine and of radiology. “Without these vaccines, more people would have gotten sick, more people would have had severe effects and more people would have died.” mRNA vaccines are viewed as a breakthrough because they can be produced quickly enough to keep up with sudden microbial strain changes and they can be rapidly adapted to fight widely divergent types of pathogens. But, as with all vaccines, not everyone who gets the shot experiences a purely benign reaction. One rare but real risk of the mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines is myocarditis, or inflammation of heart tissue. Symptoms — chest pain, shortness of breath, fever and palpitations — appear in the absence of any viral infection. And they happen quickly: within one to three days after a shot. Most of those affected have high blood levels of a substance called cardiac troponin, a well-established clinical indicator of heart-muscle injury. (Cardiac troponin is normally found exclusively in the heart muscle. When found circulating in blood, it indicates damage to heart muscle cells.).. Study published here (DEc. 10, 2025): https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.adq0143

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

December 2, 11:47 AM

|

Learn how scientists use an engineered virus for biomining rare earth elements, a green alternative to destructive, toxic mining methods. They’re gorgeous, dazzling, passionately pursued, and worth billions. No, not Hollywood starlets and hunks and the stars of K-Pop. Well, OK, yes – they are gorgeous, dazzling, passionately pursued, and worth billions – but they’re nowhere near as useful to the world as rare earth elements (REEs). And thanks to bioengineering professor Seung-Wuk Lee and his team at UC Berkeley, there’s a brand new way to make viruses that can extract REEs without causing horrific, ecosystem-killing pollution and destruction. (No word yet whether the virus can do the same for starlets, hunks, and pop-stars). In a paper recently published in the journal Nano Letters, Lee and his team describe genetically engineering a harmless virus that acts like a microscopic aquatic miner by retrieving REEs from mine drainage water, and following a temperature and pH change, delivers them for harvest. Such a method could mean an eventual replacement of the pervasive and hyper-destructive methods of modern mining. “This is a significant move toward more sustainable mining and resource recovery,” said principal investigator Seung-Wuk Lee, who is also faculty scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. “Our biological solution offers a greener, low-cost, and recyclable way to secure the critical materials we need for a clean energy future while helping to protect the environment.” Any country with REE reserves deploying such technology domestically would reduce its reliance on international sources of REEs, thus increasing its economic, industrial, and political independence. Currently, no country produces more REEs than does China, mining an estimated 240,000 tons of REEs and refining 189,179 tons in 2023. That’s 70% of the world’s REE mining and 87% of its REE refining. In their various states of oxidation, the shiny, metallic REEs can form a range of colorful compounds. While precious, the REEs aren’t exactly atomic celebrities sipping martinis and eating caviar around a glamorous periodic table. So, forget the attention-getting elements such as gold, iron, and platinum, and fix your eyes instead on this substantial crew of exotic refinement: the two transition metals scandium and yttrium, and the 15 lanthanides including promethium, europium, and gadolinium. So, how does the virus work? Lee’s team transformed a bacteriophage (a type of virus that attacks bacteria without harming humans or the rest of the biosphere) into a micro-mining machine by adding two specialized proteins. One is a lanthanide-binding peptide on the phage’s surface acting as a claw for collecting REEs, and the other, an elastin motif peptide that, when temperature-activated, exits the solution and delivers its REEs. For an outstanding bonus, the biomining viruses remain effective even after completing their “shift,” meaning they can come back to work whenever they’re needed. They’re easy and inexpensive to grow at industrial scale, too – simply add them to bacteria, and when the bacteria replicate, the virus replicates with them. According to Lee, the new biomining method is “not only eco-friendly, but also incredibly simple, requiring little more than a mixing tank and a heater.” With it, scientists “can use a programmable, biological tool to perform a complex industrial task that currently requires toxic chemicals and a lot of energy.” Because of REEs’ ability to enhance miniaturization, efficiency, durability, and performance, the world craves them. Used in consumer electronics such as mobile phones, computers, televisions and monitors, LEDs, camera lenses, fluorescent lights, REEs are also indispensable for countless industrial applications including glass-colourants, lasers, weaponry, MRIs, catalytic converters, polishing powders used in semiconductor manufacturing, fuel cells, rechargeable batteries, and vehicles for land, air, and space. REEs’ most widespread function in 2023 – about 45%, as the Government of Canada reports – is the manufacture of permanent magnets which make wind turbines and EVs (and the vibrating magnet in your cellphone) possible.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

November 19, 11:42 AM

|

Nov 19 (Reuters) - Merck (MRK.N), opens new tab said on Wednesday that its experimental oral HIV treatment was not inferior to Gilead's (GILD.O), opens new tab top-selling HIV drug Biktarvy in a late-stage study in adults with HIV who had not previously received treatment. The Rahway, New Jersey-based company was testing its oral, two-drug regimen of doravirine and islatravir in adults with HIV-1 infection who had not previously taken antiretroviral treatments, a combination of medications that work by stopping the virus from reproducing. HIV-1 is the most common strain of the retrovirus that causes Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, commonly known as AIDS. The safety profile of doravirine and islatravir was comparable to Biktarvy, Merck said. The company plans to present detailed findings from this trial at a future medical meeting and to submit applications including these data to health authorities. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is set to make its decision on approval for doravirine/islatravir by April 28, 2026. Merck's doravirine is already approved in the U.S. as a treatment for adults with HIV-1 in combination with other antiretrovirals under the brand name Pifeltro and as part of a single-tablet regimen sold under the brand name Delstrigo. Islatravir is an experimental treatment that blocks HIV-1 replication by blocking an enzyme called reverse transcriptase, which prevents the viral DNA from growing. Islatravir is currently being tested in multiple trials in combination with other antiretrovirals for potential daily and once-weekly treatments for HIV-1. Last year, the doravirine and islatravir combination treatment was shown to be non-inferior to Biktarvy in suppressing the replication of HIV-1 in patients who were already on antiretroviral therapy. Merck's Press Release (Nov. 19, 2025):

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

November 16, 11:50 AM

|

David Baker’s Nobel Prize winning lab has generated antibodies from scratch that target user-specified binding sites for AI therapeutic design. The antibody drug market value is expected to reach $445 billion in the next five years, with over 160 antibodies currently licensed globally for a wide breadth of conditions, including cancer, autoimmune diseases, and more. AI-guided rational antibody design that bypasses the need for labor intensive and time consuming experimental screens has long been a “holy grail” for protein therapeutics, says Nathaniel Bennett, PhD, co-founder of Xaira Therapeutics and former postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Nobel Laureate, David Baker, PhD, director of the Institute for Protein Design at the University of Washington (UW). In a step toward this dream, the Bennett and UW colleagues have now fine-tuned AI protein design model, RFdiffusion, to generate full length antibodies from scratch (or de novo) that can successfully bind user-specified epitopes on a therapeutic target with atomic precision. The model makes the technological advance of accurately constructing antibody loops, the key region involved in binding that has been historically challenging to design due to the flexible nature. Remarkably, binding poses of antibody designs were confirmed by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) for an array of therapeutically relevant targets, including hemagglutinin, a key protein found on the surface of influenza viruses, a potent toxin produced by the bacteria, Clostridium difficile, and PHOX2B, a peptide highly implicated in cancer. The work is described in a new study published in Nature titled, “Atomically accurate de novo design of antibodies with RFdiffusion.” Co-lead authors of the study include Bennett, Joe Watson, PhD, fellow co-founder of Xaira, and Robert Ragotte, PhD, postdoctoral researcher in the Baker lab. Xaira Therapeutics launched in April 2024 with a jaw-dropping $1 billion in committed capital and a star-studded leadership lineup—including Baker, Carolyn Bertozzi, PhD, 2022 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, Scott Gottlieb, MD, former FDA head, Alex Gorsky, former CEO of Johnson & Johnson, and more. Led by CEO Marc Tessier-Lavigne, PhD, formerly the president of Stanford University and CSO of Genentech, Xaira has publicly made big bets on the virtual cell and released the largest publicly available Perturb-seq dataset to power virtual cell models earlier this summer. In protein therapeutics, Xaira’s Seattle site is reported to be expanding Baker lab technology, including de novo antibody design. When asked to unpack the hype vs. reality debate surrounding designing proteins from scratch in a recent interview with GEN, Baker emphasizes that designing new functional proteins on a computer is now a reality and anticipates de novo design to become the competitive method of choice for a wide array of applications in the coming years. At the same time, the human body is a complicated place. “The hype is that for therapeutics, there’s a lot more than the basic activity of a protein binding or catalyzing a reaction,” explained Baker. “Whether de novo proteins will revolutionize medicine will require improving our understanding of the biology.” Rational design While traditional antibody development pipelines are limited by slow and low hit rate experimental approaches, such as animal immunizations and random library screens, de novo design has the potential to unlock access to a new trove of disease targets while speeding up drug discovery timelines by fine-tuning therapeutic properties in silico. Baker emphasizes that the study’s antibody designs do not possess the clinical properties, such as sufficiently high binding affinity, to progress as a drug. However, the de novo proof-of-concept provides a powerful tool to augment rational therapeutic design workflows. “When you select antibodies from a yeast library or animal immunization, you don’t have much control over [drug features]. With rational design, it will be possible to systemically incorporate beneficial properties,” Baker told GEN. Bennett adds that while early RFdiffusion-designed proteins were small mini-binders characterized in the lab, full length therapeutic antibodies must function in the human body. “You can imagine that developability is difficult to optimize if you only have a linear antibody sequence. It’s hard to know how mutations will disrupt binding or stability of the antibody,” explained Bennett in an interview with GEN. “We’re excited about what is now possible in improving developability properties with fully atomically accurate information.” Additionally, structural precision can aid the targeting of key “hard to drug” classes, such as G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs). GPCRs represent approximately one-third of drug targets, yet are notoriously hard to drug because achieving therapeutic function involves modulating very small structural differences to shift the protein between active and inactive states. Ragotte highlights that another key offering of the study’s design pipeline is the modularity to accommodate new methods. As the original antibody workflow was constructed before the release of AlphaFold 3, which made the advance of modeling biomolecular complexes, the UW researchers showed that the workflow could be adapted to apply AlphaFold 3 to filter designs, which led to overall higher success rates. “Swapping out one part of the pipeline with a new update is a value of this modularity because you can rapidly incorporate improvements both from within the lab and externally,” Ragotte told GEN. Future directions of the work aim to further raise experimental success rates for computational antibody designs and improve binding affinity for clinical relevance. Research published in Nature (Nov. 5, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09721-5

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

November 14, 10:40 AM

|

A Grays Harbor County resident has tested preliminarily positive for avian influenza in the first human case recorded in Washington state this year. The resident, an older adult with underlying health conditions, was hospitalized in early November with a high fever, confusion and respiratory distress, the state Department of Health said in a news release Thursday. They’re currently receiving treatment at a King County hospital, health officials said. Further testing to confirm the bird flu case is pending, Dr. Tao Sheng Kwan-Gett, the state’s health officer, said in a Thursday news briefing. Public health teams are also still working to determine the source of infection, he added. The health department declined to share further information about the person’s age or gender, citing patient privacy, but Kwan-Gett said the risk to the general public remains low...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

November 8, 12:24 PM

|

A new lipid nanoparticle makes mRNA vaccines 100 times more potent and could reduce vaccine dosage and costs. The advent of mRNA vaccination, ignited by the COVID-19 pandemic, has sparked research to build the next generation of vaccine. Specifically, to address limitations of current mRNA vaccines—such as increasing vaccine potency and reducing toxicity. Now, a new delivery LNP, developed through sequential combinatorial chemistry and rational design, and based on a class of degradable, cyclic amino ionizable lipids, has been developed at MIT. The novel LNP could make mRNA vaccines more effective and potentially lower the cost per vaccine dose. In mouse studies, the researchers showed that an mRNA influenza vaccine delivered with their new LNP could generate the same immune response as mRNA delivered by nanoparticles made with FDA-approved materials, but at around 1/100 the dose. “One of the challenges with mRNA vaccines is the cost,” says Daniel Anderson, PhD, professor in MIT’s department of chemical engineering and a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and Institute for Medical Engineering and Science (IMES). “Our goal has been to try to make nanoparticles that can give you a safe and effective vaccine response but at a much lower dose.” The team sought to develop particles that can induce an effective immune response, but at a lower dose than the particles currently used to deliver COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. That could not only reduce the costs per vaccine dose, but may also help to lessen the potential side effects, the researchers say. LNPs typically consist of five elements: an ionizable lipid, cholesterol, a helper phospholipid, a polyethylene glycol lipid, and mRNA. This work focused on the ionizable lipid, which plays a key role in vaccine strength. The researchers designed a library of new ionizable lipids containing cyclic structures which can help enhance mRNA delivery, as well as esters, which the researchers hypothesized could help improve biodegradability. Using a luciferase reporter, combinations of the structures were screened in mice for effective delivery. A second screen was performed with variants from the top-performing particle. From these screens, AMG1541 was determined to be more effective in dealing with endosomal escape, a major barrier for delivery particles. Another advantage of the new LNPs is that the ester groups in the tails make the particles degradable once they have delivered their cargo so that they can be cleared from the body quickly. The researchers believe this could reduce side effects from the vaccine. The team used the AMG1541 LNP to deliver an mRNA influenza vaccine in mice. They compared this vaccine’s effectiveness to a flu vaccine made with the lipid SM-102, which is FDA-approved and was used by Moderna in its COVID-19 vaccine. Mice vaccinated with the new particles generated the same antibody response as mice vaccinated with the SM-102 particle, but only 1/100 of the dose was needed to generate that response, the researchers found. “It’s almost a hundredfold lower dose, but you generate the same amount of antibodies, so that can significantly lower the dose. If it translates to humans, it should significantly lower the cost as well,” says Arnab Rudra, PhD, a visiting scientist at the Koch Institute. In addition, the AMG1541 mRNA LNPs “substantially reduced expression in the liver following intramuscular injection, mitigating the associated toxicity.” In addition, the researchers observed “improved mRNA delivery to antigen-presenting cells at the injection site and the draining lymph node, leading to stronger germinal center reactions.” The new LNPs are also more likely to accumulate in the lymph nodes, where they encounter many more immune cells. “We have found that they work much better than anything that has been reported so far. That’s why, for any intramuscular vaccines, we think that our LNP platforms could be used to develop vaccines for a number of diseases,” says Akash Gupta, PhD, a Koch Institute research scientist. Published in Nat. Nanotechnology (N0v. 07, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-025-02044-6

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

November 5, 11:14 AM

|

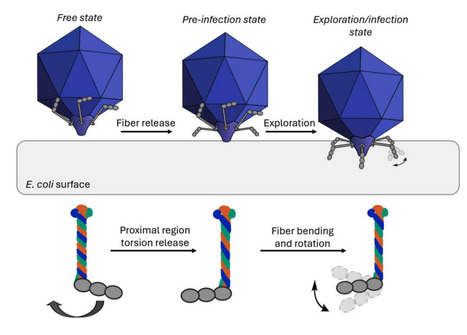

Viruses are nanoscale infectious agents capable of specifically targeting and reprograming host cells. A unique group of viruses, bacteriophages, have regained popularity in research partly due to the rising number of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections. Phages could potentially replace antibiotics, but only if we understand every detail of their structure and infection cycle. T7 bacteriophages are a group of dsDNA viruses, which infect E. coli bacteria. T7 virions are comprised of an icosahedral protein shell which encapsulates the genomic DNA, and a tail-fiber complex which is primarily used for target recognition and DNA injection. The virus has six” L”-shaped, ∼40 nm long fibers (gp17 protein trimers) attached to the tail-tube, which are thought to be essential for initial host recognition and possibly surface exploration. Using high-speed atomic force microscopy (HS-AFM) and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations combined with small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) we observed the molecular structure and movements of isolated tail fibers. Firstly, we have identified a hinge region within the fibers, which makes them highly flexible, allowing the bending of their distal region. Furthermore, we have observed the dynamic triple helical coiled coil structure of the proximal region, which would allow fiber rotation. These two points of flexibility allow a more efficient and highly dynamic host recognition and virus anchoring process. The observed flexibility might allow host surface exploration by walking. Such flexibility in the host recognition machinery may not be unique to T7 bacteriophages, getting us one step closer to understanding the intricate details of virus-host interactions. Preprint available in bioRxiv (October 22, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.10.22.683886

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

October 29, 10:51 AM

|

Since 2020, high pathogenicity avian influenza virus (HPAIV) infections in wild birds have been frequently reported. Because HPAIV infection has occasionally caused outbreaks in captive rare birds, application of antiviral drugs for treatment purposes against them has been considered from the perspective of conservation medicine. In this study, the therapeutic efficacy of baloxavir marboxil (BXM) was evaluated using a duck model to help establish the post-infection treatment for rare birds. Sixteen four-week-old ducks were divided into four groups and intranasally inoculated with the HPAIV strain A/crow/Hokkaido/0103B065/2022 (H5N1). BXM was orally administered once daily at doses of 12.5, 2.5, 0.5, and 0 mg/kg to each of the four groups from 2 to 6 days post-infection. Blood samples were collected at 2, 8, and 24 hours after the initial BXM administration to measure the plasma concentrations of its active form, baloxavir acid (BXA). All ducks were monitored until 14 days post-infection, and their oral and cloacal swabs were collected for virus recovery. All eight ducks administered with 12.5 or 2.5 mg/kg of BXM survived, demonstrating a significant reduction in virus recovery compared to the 0 mg/kg group. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) analysis of BXA suggested that parameters such as Cmax and AUC0–24hr were correlated with the suppression of virus shedding. These findings demonstrated that BXM administration within 48 hours post-HPAIV infection in ducks effectively reduced mortality and virus shedding. The comparison of PK parameters may help estimate efficient BXM dosing strategies in rare birds. Preprint in medRxiv (October 28, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.10.24.684283

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

October 27, 12:31 PM

|

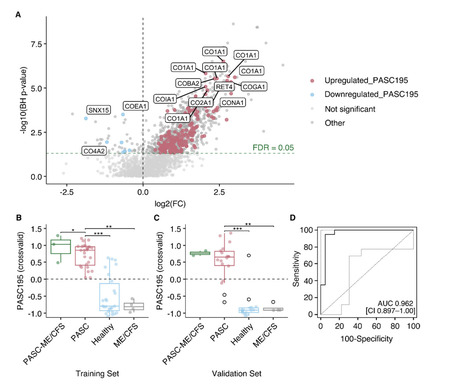

Background Post-acute sequelae of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-infection (PASC) is challenging to diagnose and treat, and its molecular pathophysiology remains unclear. Urinary peptidomics can provide valuable information on urine peptides that may enable improved and specified PASC diagnosis. Methods Using standardized capillary electrophoresis-MS, we examined the urinary peptidomes of 50 patients with PASC 10 months after COVID-19 and 50 controls including healthy individuals (n = 42) and patients with non-COVID-19-associated myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (n = 8). Based on peptide abundance differences between cases and controls, we developed a diagnostic model using a support vector machine. Results The abundance of 195 urine peptides among PASC patients significantly differed from that in controls, with a predominant abundance of collagen alpha chains. This molecular signature (PASC195), effectively distinguished PASC cases from controls in the training set [AUC of 0.949 (95% CI 0.900–0.998; p < 0.0001)] and independent validation set [AUC of 0.962 (95% CI 0.897–1.00); p < 0.0001)]. In silico assessment suggested exercise, GLP1-RA and MRA as potentially efficacious interventions. Conclusions We present a novel and non-invasive diagnostic model for PASC. Reflecting its molecular pathophysiology, PASC195 has the potential to advance diagnostics and inform therapeutic interventions. Statement of significance of the study Despite the recent emergence of omics-derived candidates for post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), the pending validation of proposed markers and lack of consensus result in the continuous reliance on symptom-based criteria, being subject to diagnostic uncertainties and potential recall bias. Building upon prior findings of renal involvement in acute COVID-19 pathophysiology and PASC-associated alterations, we hypothesized that the use of urinary peptides for PASC-specific biomarker discovery, unlike conventional specimens that have been utilized thus far, may offer complementary information on putative disease mechanisms. In the present study, 195 significantly expressed peptides were used to form a classifier termed PASC195, which effectively discriminated PASC from non-PASC (p < 0.0001), including healthy individuals and non-COVID-19 associated myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, in both the derivation (n = 60) and an independent validation set (n = 40). Shift in collagen regulation was associated with PASC, as the majority of PASC195 peptides were derived from collagen alpha chains. Ongoing inflammatory responses, hemostatic imbalances, and endothelial damage were inferred from cross-sectional variations in endogenous peptide excretion. Available in medRxiv (October 27, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.10.15.25338065

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

October 24, 11:53 AM

|

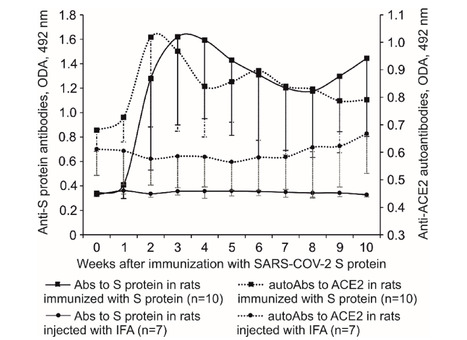

SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to induce autoimmunity. Due to the idiotype-antiidiotypic interactions between lymphocytes to SARS-CoV-2 S protein and lymphocytes to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the immune response to S protein can cause induction of anti-ACE2 lymphocytes. The ubiquity of ACE2 within the human body endows autoimmune reactions to ACE2 with the role of the main factor causing injuries of various tissues. Immunization of Wistar rats with S protein caused hyperplasia and dedifferentiation of type II pneumocytes, extensive injury of the proximal tubules, infiltration of CD4+ T, CD45RA+ B lymphocytes in the lungs and CD4+ T, CD8+ T lymphocytes in the kidneys. Both type II pneumocytes and proximal tubule epithelium express ACE2. Damage to ACE2 expressing cells in the absence of other lesions in the studied organs suggests that ACE2 might be the target of an autoimmune attack induced by S protein. Our findings clarify the mechanism of multiple tissue damage in COVID-19. Published (Oct. 24, 2025) in Scientific Reports: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21304-y

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

October 21, 12:30 PM

|