|

Scooped by

Guillaume Decugis

onto Ideas for entrepreneurs September 30, 2021 10:13 PM

|

Follow, research and publish the best content

Get Started for FREE

Sign up with Facebook Sign up with X

I don't have a Facebook or a X account

Already have an account: Login

Serial entrepreneurship is constant learning.

Here's what I found impacting.

Here's what I found impacting.

Curated by

Guillaume Decugis

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

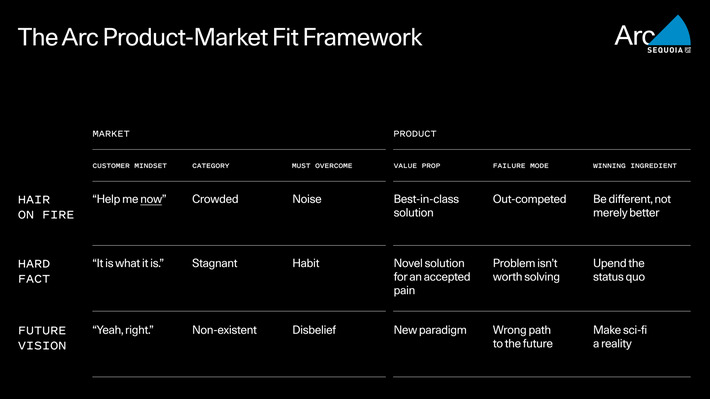

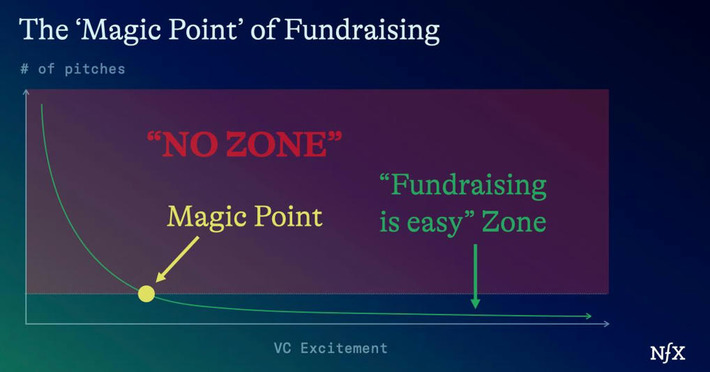

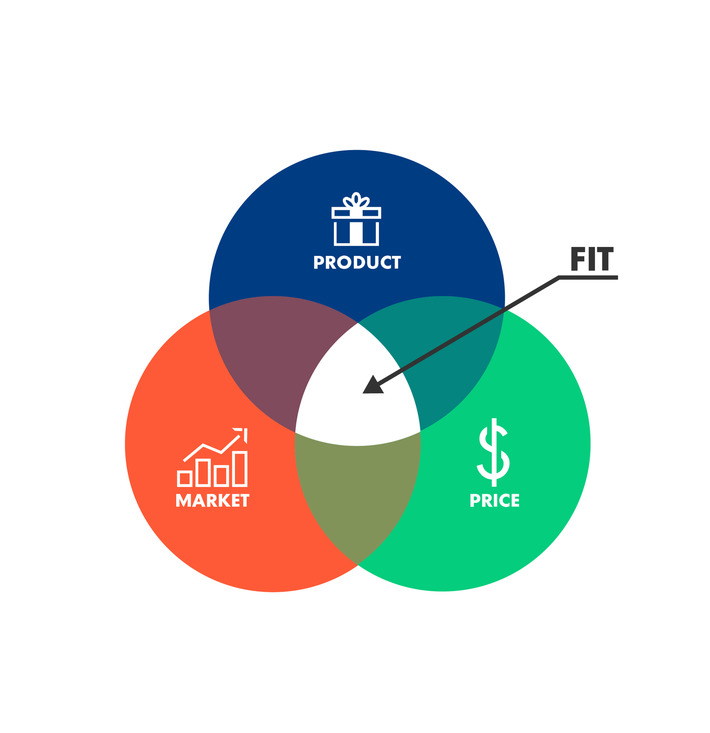

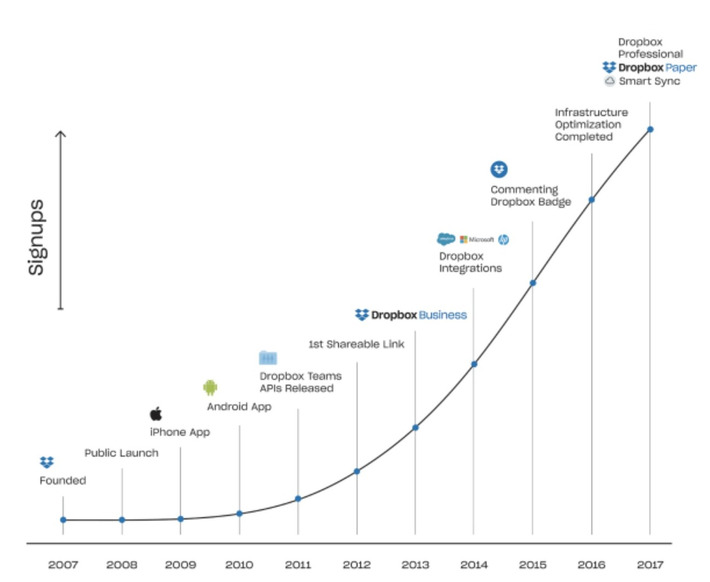

Can entrepreneurship be taught? That’s an old debate but my friend Pierre Gaubil has a more interesting question: can a startup chances of success be improved? And he makes a convincing case that yes, by applying a robust methodological framework that leverages the collective intelligence we’ve built over decades of tech innovation.