Your new post is loading...

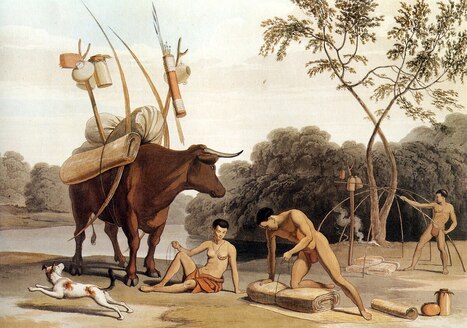

Hottentot (English and German language /ˈhɒtənˌtɒt/ HOT-ən-TOT) is a term that was historically used by Europeans to refer to the Khoekhoe, the indigenous nomadic pastoralists in South Africa. Use of the term Hottentot is now considered offensive, the preferred name for the non-Bantu speaking indigenous people of the Western Cape area being Khoekhoe (formerly Khoikhoi).[a] Etymology Hottentot originated among the "old Dutch" settlers of the Dutch Cape Colony run by United East India Company (VOC), who arrived in the region in the 1650s,[5] and it entered English usage from Dutch in the seventeenth century.[6] However, no definitive Dutch etymology for the term is known. A widely claimed etymology is from a supposed Dutch expression equivalent to "stammerer, stutterer", applied to the Khoikhoi on account of the distinctive click consonants in their languages. There is, however, no earlier attestation of a word hottentot to support this theory. An alternative possibility is that the name derived from an overheard term in chants accompanying Khoikhoi or San dances, but seventeenth-century transcriptions of such chants offer no conclusive evidence for this.[6] An early Anglicisation of the term is recorded as hodmandod in the years around 1700.[7] The reduced Afrikaans/Dutch form hotnot has also been borrowed into South African English as a derogatory term for black people, including Cape Coloureds.[8] Usage as an ethnic term In seventeenth-century Dutch, Hottentot was at times used to denote all black people (synonymously with Kaffir, which was at times likewise used for Cape Coloureds and Khoisans), but at least some speakers used the term Hottentotspecifically for what they thought of as a race distinct from the supposedly darker-skinned people referred to as Kaffirs. This distinction between the non-Bantu "Cape Blacks" or "Cape Coloureds" and the Bantu was noted as early as 1684 by the French anthropologist François Bernier.[9] The idea that Hottentot referred strictly to the non-Bantu peoples of southern Africa was well embedded in colonial scholarly thought by the end of the eighteenth century.[10] The main meaning of Hottentot as an ethnic term in the 19th and the 20th centuries has therefore been to denote the Khoikhoi people specifically.[11] However, Hottentot also continued to be used through the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries in a wider sense, to include all of the people now usually referred to with the modern term Khoisan(not only the Khoikhoi, but also the San people, hunter-gatherer populations from the interior of southern Africa who had not been known to the seventeenth-century settlers, once often referred to as Bosjesmannen in Dutch and Bushmen in English).[12][13] In George Murdock's Atlas of World Cultures (1981), the author refers to "Hottentots" as a "subfamily of the Khoisan linguistic family" who "became detribalized in contact with Dutch settlers in 1652, mixing with the latter and with slaves brought by them from Indonesia to form the hybrid population known today as the Cape Coloured."[14] The term Hottentot remained in use as a technical ethnic term in anthropological and historiographical literature into the late 1980s.[15] The 1996 edition of the Dictionary of South African English merely says that "the word 'Hottentot' is seen by some as offensive and Khoikhoi is sometimes substituted as a name for the people, particularly in scholarly contexts".[16] Yet, by the 1980s, because of the racist connotations discussed below, it was increasingly seen as too derogatory and offensive to be used in an ethnic sense.[17] Usage as a term of abuse and racist connotations From the eighteenth century onwards, the term hottentot was also a term of abuse without a specific ethnic sense, comparable to barbarian or cannibal.[18] According to James Boswell's The Life of Johnson, Samuel Johnson was parodied in Lord Chesterfield's Letters of 1737 as "a respectable Hottentot". In its ethnic sense, Hottentot had developed its connotations of savagery and primitivism by the seventeenth century; colonial depictions of the Hottentots (Khoikhoi) in the seventeenth to eighteenth century were characterized by savagery, often suggestive of cannibalism or the consumption of raw flesh, physiological features such as steatopygiaand elongated labia perceived as primitive or "simian" and a perception of the click sounds in the Khoikhoi languages as "bestial".[19] Thus, it can be said that the European, colonial image of "the Hottentot" from the seventeenth century onwards bore little relation to any realities of the Khoisan in Africa, and that this image fed into the usage of hottentotas a generalised derogatory term.[20] Correspondingly, the word is "sometimes used as ugly slang for a black person".[21] Use of the derived term hotnot was explicitly proscribed in South Africa by 2008.[22] Accordingly, much recent scholarship on the history of colonial attitudes to the Khoisan or on the European trope of "the Hottentot" puts the term Hottentot in scare quotes.[23] Other usages In its original role of ethnic designator, the term Hottentot was included into a variety of derived terms, such as the Hottentot Corps,[24] the first Coloured unit to be formed in the South African army, originally called the Corps Bastaard Hottentoten (Dutch; in English: "Corps Bastard Hottentots"), organised in 1781 by the Dutch colonial administration of the time.[25]: 51 The word is also used in the common names of a wide variety of plants and animals,[26] such as the Africanis dogs sometimes called "Hottentot hunting dogs", the fish Pachymetopon blochii, frequently simply called hottentots, Carpobrotus edulis, commonly known as a "hottentot-fig", and Trachyandra, commonly known as "hottentot cabbage". It has also given rise to the scientific name for one genus of scorpion, Hottentotta, and may be the origin of the epithet tottum in the botanical name Leucospermum tottum.[27] The word is still used as part of a tongue-twister in modern Dutch, "Hottentottententententoonstelling", meaning a "Hottentot tent exhibition".[28] In the 1964 film Mary Poppins, Admiral Boom mistakes the rooftop-dancing chimney sweeps for an attack by "Hottentots". In 2024, the BBFC raised the film's age rating from U to PG due to this instance of "discriminatory language".[29] The name of Reiner Knizia's game "Schotten-Totten" is a portmanteau of the German words "Schotten" (Scottish people) and "Hottentotten" (Hottentots).[citation needed] The Shakespears Sister song "I Don't Care", from the 1992 album Hormonally Yours, includes the lines: "In a boreolic iceberg came Victoria; Queen Victoria, sitting shocked upon on the rocking horse of a wave, Said to the Laureat, this minx of course, Is sharp as any lynx, and blacker, deeper Than the drinks, as hot as any hottentot." See also Look up Hottentot in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. Notes - "Khoisan" is an artificial compound term that was introduced into 20th-century ethnology, but since the late 1990s it has been adopted as a self-designation. Since 2017, its use has been official due to the passage of a Traditional & Khoisan Leadership Bill by the South African National Assembly.[2][3][4]

The indigenous people of Africa are groups of people native to a specific region; people who lived there before colonists or settlers arrived, defined new borders, and began to occupy the land. This definition applies to all indigenous groups, whether inside or outside of Africa. Although the vast majority of Native Africans can be considered to be "indigenous" in the sense that they originated from that continent and nowhere else (like all Homo sapiens), identity as an "indigenous people" is in the modern application more restrictive. Not every African ethnic group claims identification under these terms. Groups and communities who do claim this recognition are those who by a variety of historical and environmental circumstances have been placed outside of the dominant state systems. Their traditional practices and land claims have often come into conflict with the objectives and policies promulgated by governments, companies, and surrounding dominant societies. Marginalization, along with the desire to recognize and protect their collective and human rights, and to maintain the continuity of their individual cultures, has led many to seek identification as indigenous peoples, in the contemporary global sense of the term. For example, in West Africa, the Dogon people of Mali and Burkina Faso,[1][2] the Jola people of Guinea-Bissau, The Gambia, and Senegal,[3] and the Serer people of Senegal, The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, and Mauritania, and formally North Africa,[4][5] have faced religious and ethnic persecution for centuries, and disenfranchisement or prejudice in modern times (see Persecution of Serers and Persecution of Dogons). These people, who are indigenous to their present habitat, are classified as indigenous peoples.[1][2][3][4] History The history of the indigenous African peoples spans thousands of years and includes a complex variety of cultures, languages, and political systems. Indigenous African cultures have existed since ancient times, with some of the earliest evidence of human life on the continent coming from stone tools and rock art dating back hundreds of thousands of years. The earliest written records of African history come from ancient Egyptian and Nubian texts, which date back to around 3000 B.C. These texts provide insight into the societies of the time, including religious beliefs, political systems, and trade networks. In the centuries that followed, various other African civilizations rose to prominence, such as the Kingdom of Kush in northern Sudan and the powerful empires of Ghana, Mali, and Songhaiin West Africa. Arab colonization of Northern Africa displaced and dispossessed indigenous African peoples. In the late 15th century, European colonization began, leading to the further displacement of many indigenous cultures. Since the end of World War II, indigenous African cultures have been in a state of constant flux, struggling to maintain their identity in the face of Westernization and globalization. In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in traditional cultures and many African countries have taken steps to preserve and promote their indigenous heritage. "Indigenous" in the contemporary African context San people in Namibia In the post-colonial period, the concept of specific indigenous peoples within the African continent has gained wider acceptance, although not without controversy. The highly diverse and numerous ethnic groups which comprise most modern, independent African states contain within them various peoples whose situation, cultures, and pastoralist or hunter-gatherer lifestyles are generally marginalized and set apart from the dominant political and economic structures of the nation. Since the late 20th century, these peoples have increasingly sought recognition of their rights as distinct indigenous peoples, in both national and international contexts. The Indigenous Peoples of Africa Co-ordinating Committee (IPACC) was founded in 1997. It is one of the main trans-national network organizations recognized as a representative of African indigenous peoples in dialogues with governments and bodies such as the UN. In 2008, IPACC was composed of 150 member organisations in 21 African countries. IPACC identifies several key characteristics associated with indigenous claims in Africa: - "political and economic marginalization rooted in colonialism;

- de facto discrimination often based on the dominance of agricultural peoples in the State system (e.g. lack of access to education and health care by hunters and herders);

- the particularities of culture, identity, economy and territoriality that link hunting and herding peoples to their home environments in deserts and forests (e.g. nomadism, diet, knowledge systems);

- some indigenous peoples, such as the San and Pygmy peoples, are physically distinct, which makes them subject to specific forms of discrimination."

African Pygmies northeastern Congo posing with bows and arrows (c. 1915) With respect to concerns that identifying some groups and not others as indigenous is in itself discriminatory, IPACC states that it: - "... recognises that all Africans should enjoy equal rights and respect. All of Africa's diversity is to be valued. Particular communities, due to historical and environmental circumstances, have found themselves outside the state-system and underrepresented in governance... This is not to deny other Africans their status; it is to emphasize that affirmative recognition is necessary for hunter-gatherers and herding peoples to ensure their survival."

At an African inter-governmental level, the examination of indigenous rightsand concerns is pursued by a sub-commission established under the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights (ACHPR), sponsored by the African Union (AU) (successor body to the Organisation of African Unity (OAU)). In late 2003, the 53 signatory states of the ACHPR adopted the Report of the African Commission's Working Group on Indigenous Populations/Communities and its recommendations. This report says in part (p. 62): - "... certain marginalized groups are discriminated in particular ways because of their particular culture, mode of production and marginalized position within the state[; a] form of discrimination that other groups within the state do not suffer from. The call of these marginalized groups to protection of their rights is a legitimate call to alleviate this particular form of discrimination."

The adoption of this report at least notionally subscribed the signatories to the concepts and aims of furthering the identity and rights of African indigenous peoples. The extent to which individual states are mobilizing to put these recommendations into practice varies enormously, however. Most indigenous groups continue to agitate for improvements in the areas of land rights, use of natural resources, protection of environment and culture, political recognition and freedom from discrimination. On 30 December 2010, the Republic of Congo adopted a law for the promotion and protection of the rights of indigenous peoples. This law is the first of its kind in Africa, and its adoption is a historic development for indigenous peoples on the continent.[6] See also

The Kalahari Debate is a series of back and forth arguments that began in the 1980s amongst anthropologists, archaeologists, and historians about how the San people and hunter-gatherer societies in southern Africa have lived in the past. On one side of the debate were scholars led by Richard Borshay Leeand Irven DeVore, considered traditionalists or "isolationists." On the other side of the debate were scholars led by Edwin Wilmsen and James Denbow, considered revisionists or "integrationists."[citation needed] Lee conducted early and extensive ethnographic research among a San community, the !Kung San. He and other traditionalists consider the San to have been, historically, isolated and independent hunter/gatherers separate from nearby societies. Wilmsen, Denbow and the revisionists oppose these views. They believe that the San have not always been an isolated community, but rather have played important economic roles in surrounding communities. They claim that over time the San have become a dispossessed and marginalized people.[citation needed] Both sides use both anthropological and archaeological evidence to fuel their arguments. They interpret cave paintings in Tsodilo Hills, and they also use artifacts such as faunal remains of cattle or sheep found at San sites. They even find Early Stone Age and Early Iron Age technologies at San sites, which both sides use to back their arguments.[citation needed] Traditionalists The San are a relatively small group of people whose communities are scattered throughout the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa. They are well known for practicing a hunter/gatherer subsistence strategy (also known as a "foraging" mode of production).[1] Traditionalists, including Richard Lee and other anthropologists, view the San as maintaining this old but adaptable way of life, even in the face of changing external circumstances. San Hunter These anthropologists view the San as isolates who are not, and have never been, part of a greater Kalahari economy. The traditionalists believe that the San have adapted over time but without help from other societies. Emphasis is thereby placed on the cultural continuity and the cultural integrity of the San peoples.[2] In Lee's 1979 book The !Kung San: Men, Women, and Work in a Foraging Society, his main goal was to be fully immersed in the !Kung San culture so that he could fully understand their way of life. He was puzzled as to how these people seemed to be living such an easy and happy life that relied heavily on hard work and the availability of food. Most of his studies of the San took place in the Dobe area, near the Tsodilo Hills. He was adopted into a kinship and given the name /Tontah which meant “White-Man.” He claims that the San were an isolated hunter-gatherer society that changed to farming and foraging at the end of the 1970s. Most of Lee's historical data comes from oral stories told by the !Kung San because they did not have anything written down. According to Lee the San were originally afraid of contact with outsiders.[citation needed] Lee reports that the men did the hunting and hard labor while the women did housework. He later found out that the San weren't just hunter-gatherers, but also herders, foragers, and farmers. In his book he states, “I learned that most of the men had had experience herding cattle at some point in their lives and that many men had owned cattle and goats in the past.”[3] He claims that they have learned all of this on their own. The San wanted wage pay for farming and taking care of cattle, goats, and sheep. This was their new way of life.[clarification needed] Revisionists The San "Bushmen" Edwin Wilmsen's 1989 book Land Filled With Flies kicked off the Kalahari Debate.[citation needed] Wilmsen made several remarks attacking anthropologists’ view of the San people. Most of his attacks were at Richard Lee and his work. Wilmsen made claims about the San such as, “Their appearance as foragers is a function of their relegations to an underclass in the playing out of historical processes that began before the current millennium and culminated in the early decades of this century.”[4] This statement upsets the traditionalists because it says that the San are not isolates but have been an underclass in a society throughout history. Wilmsen makes another statement against the traditionalists when he says, “The isolation in which they are said to have been found is a creation of our own view of them, not of their history as they lived it.”[4] He is beginning to say that anthropologists’ judgment is clouded because they already have a predisposed view of the San and hunter-gatherer societies as being isolates. Wilmsen states that the terms “Bushmen,” “Forager,” and “Hunter-Gatherer” contribute to the ideology of them being isolates. He says this is because these terms are commonly associated with isolated groups but his main claim is that for the San this is not the case. Wilmsen also goes on to claim that Lee approaches the San as a people without a history, that they have been doing the same thing forever. He states, “they are permitted antiquity while denied history”[4] Wilmsen continues the argument that anthropologists’ goal is to study hunter-gatherer groups who have lived on their own for centuries, which builds a stereotype for hunter-gatherers. He believes this is why Richard Lee's views are flawed, and also why he[clarification needed] is saying that the San are incorporated in a wider political economy in southern Africa.[citation needed] The revisionists believe the !Kung were associated with Bantu-speaking overlords throughout history, and involved with merchant capital.[1] They believe the San in the Kalahari are a classless society because they are actually the lower class of a greater Kalahari society. The revisionists believe the !Kung San were heavily involved in trade. They believe the San were transformed by centuries of contact with Iron Age, Bantu-speaking agro-pastoralists.[2] This argues against the idea that they were a well-adapted hunter-gatherer culture, but instead advanced only through trade and help from nearby economies.[citation needed] Archaeological evidence Tsodilo Rock Art When it comes to archaeological evidence, much work still has yet to be done. However, artifacts and ecofacts have been found at southern African sites that could help prove the revisionist view of the San people. Their strongest supporting site is in the Tsodilo Hills, where rock art displays San looking over Bantu cattle. In the hills, there are 160 cattle pictures, 10 of which display stick figures near them.[citation needed] Other evidence revisionists point to includes Early Iron Age products found in Later Stone Age sites. This includes metal and pottery found in the Dobe, Xia, and Botswana regions. Cow bones have also been found in northern Botswana, at Lotshitshi. These products are believed to be payment to the San for labor of caring for or possibly herding Bantu cattle.[citation needed] Continuing debates The fuel of this debate is the constant back and forth critiquing by various scholars of each other's work. Wilmsen would say Lee is blinded by a pre-destined view of the San as isolates. Lee would counter-argue every point that Wilmsen would make, saying either that he made mistakes in research or presents conclusions with little evidence to support them.[citation needed] One specific instance is where Lee called out Wilmsen for mistaking the word “oxen” for “onins”, which meant “onions” in an old map of the Kalahari region.[1] This discovery would make the San herders before the arrival of the anthropologists in the 1950s and 1960s and not after the 1970s, as Lee believes. This instance gave rise to Lee's article "Oxen or Onions." In the article, Lee points out other flaws he believes he has found in Wilmsen's argument. Critiques of Wilmsen's work say that the cattle paintings could represent San stealing cattle rather than herding them. Another attack on Wilmsen's work was that the amounts of pottery and iron found in Dobe and Botswana regions were so small they could fit in one hand.[2] The small numbers of these artifacts make some scholars believe they are insufficient to be able to make such a claim. The same is true of the cattle bones found in Botswana. The small numbers of cattle bone fragments found on San archaeological sites have made scholars question Wilmsen's argument.[2]

Legal Framework The statutory and regulatory framework in which sound records management is founded is the following: The Constitution, 1996 Section 195 of the Constitution provides amongst others for the: - effective, economical and efficient use of resources;

- provision of timely, accessible and accurate information; and requires that

- the public administration must be accountable.

The National Archives and Records Service of South Africa Act (Act No. 43 of 1996, as amended) Section 13 of the Act contains specific provisions for efficient records management in governmental bodies. It provides for the National Archivist- - to determine which record keeping systems should be used by governmental bodies;

- to authorize the disposal of public records or their transfer into archival custody; and

- to determine the conditions -

- according to which records may be microfilmed or electronically reproduced; - according to which electronic records systems should be managed. The National Archives and Records Service of South Africa Regulations (R158 of 20 November 2002) Part V: Management of Records contains the specific parameters within which the governmental bodies should operate regarding the management of their records. The Public Finance Management Act (Act No. 1 of 1999) and the Municipal Finance Management Act (Act No. 56 of 2003) The purpose of the Act is to regulate financial management in the public service and to prevent corruption, by ensuring that all governmental bodies manage their financial and other resources properly. The Promotion of Access to Information Act (Act No. 2 of 2000) The purpose of the Act is to promote transparency, accountability and effective governance by empowering and educating the public – 1. to understand and exercise their rights; 2. to understand the functions and operation of public bodies; and 3. to effectively scrutinize, and participate in, decision-making by public bodies that affects their rights. As far as the Promotion of Access to Information Act is concerned, the definition of a record is similar to that in the National Archives and Records Service Act, namely “recorded information regardless of form or medium”. Governmental bodies cannot refuse access on grounds that a record is in an electronic form (including an e-mail). This implies that an electronic record (including an e-mail) like any other record should be managed in such a manner that it is available, accessible, and rich in contextual information. By implication electronic records (including e-mails) should be managed in proper record keeping systems and the disposal of electronic records (including e-mails) should be documented and executed with the necessary authority. The Promotion of Administrative Justice Act (Act No. 3 of 2000) The purpose of the Act is to ensure that administrative action is lawful, reasonable and fair and properly documented. The Promotion of Administrative Justice Act imposes a duty on the state to ensure that administrative action is lawful, reasonable and procedurally fair; and everyone whose rights have been adversely affected by administrative action has the right to be given written reasons for such an action. The Electronic Communications and Transactions Act (Act No. 25 of 2002) The purpose of the Act is to legalize electronic communications and transactions, and to built trust in electronic records. According to the Electronic Communications and Transactions Act data messages are legally admissible records, provided that their authenticity and reliability as true evidence of a transaction can be proven beyond any doubt. The evidential weight of the electronic records (including e-mails) would depend amongst others on the reliability of the manner in which the messages were managed by the originator and the receiver. Should bodies not have a properly enforced records management and e-mail policy and a reliable and secure record keeping system, they run the risk that the evidential weight of their electronic records (including e-mails) might be diminished. Efficient records management practices are imperative if a body wants to give effect to the provisions of these Acts.

Indigenous Land: Bo-Kaap Khoena History vs Slavery Descendants

The Bo-Kaap area is not primarily known for its Khoi history, but rather as a historic area with a strong Muslim identity, developed from the 1780s by freed slaves and artisans, many of whom were brought to the Cape as part of the Dutch East India Company's slave trade. While the Khoi people were the original inhabitants of the Cape, their history is distinct from the development of the Bo-Kaap as a community of freed slaves and their descendants. Here's a more detailed look: -

Khoi People: The Khoi (also spelled Khoekhoe) were the original inhabitants of the Cape region, pastoralists with their own social structures and way of life. They had a long history in the area before European colonization. -

Bo-Kaap's Origins: The Bo-Kaap, originally known as the Malay Quarter, developed later, around the 1760s, as a place where freed slaves and political exiles were housed. -

Diverse Origins: The community in Bo-Kaap includes people of various backgrounds, including those from Malaysia, Indonesia, and other parts of Africa, who were brought to the Cape as slaves. -

Muslim Community: Over time, the Bo-Kaap became predominantly Muslim, and many consider it the traditional home of the Cape Malays. The first mosque in South Africa was built in the Bo-Kaap, and it holds significant religious and cultural importance. -

Distinct Histories: While the Khoi were displaced and impacted by colonization, the Bo-Kaap's history is tied to the experience of slavery, emancipation, and the development of a distinct Muslim community. -

Fighting for Heritage: The Bo-Kaap community has faced challenges, including attempts to displace them and preserve their unique heritage, including their colorful houses and vibrant culture. In short, while the Khoi people were the original inhabitants of the Cape, the Bo-Kaap's history is specifically tied to the experiences of freed slaves and their descendants who established a vibrant Muslim community in the area.

Development Dispute of the Goringhaiqua Goringhaicona Goraichouqua Indigenous Khoena Royal Kingdom Council Two Rivers Urban Park

Goringhaiqua Goringhaicona Goraichouqua Council lost the ability to protect a significant environmentally sensitive site on a flood plain, which is under threat of a 4 billion rand development being proposed by the Liesbeeck Leisure Trust (River Club developers) and supported by the City of Cape Town. It is situated in the Two Rivers Urban Park, in Observatory, Cape Town. Currently, this precinct, as we understand it, is under an urgent environmental and heritage threat. Background and Rationale This site is where the establishment of the First Freeburgher farms in 1657, which led to the first Khoi War of 1659 to 1660 (which precipitated in sixteen more wars) and the palisade fence erected by Jan Van Riebeeck were a combined catalyst, which over time, resulted in the decimation of various animals endemic to the region, and the devastation of indigenous floral kingdoms. This was accompanied by the genocide of the Cape San, as well as, the forced removal, forced migration, and ethnocide of various Khoena groups all the way up to Namibia. The brutal can-hunting until extinction of the Quagga, the Blue Buck and Cape Lion, all of which hold symbolic and spiritual resonance for the Khoi, created a physical fracture in the close symbiotic relationship with nature that determined the essence of being of the indigene. Beside the Western Leopard Toad and the Cape Otter, and various flora, the primary heritage informant is the intangible history related to the 'peopling' on the banks of two sacred rivers, amplified at the confluence of the Black River and Liesbeeck River. This confluence is a revered sacred site for the Goringhaiqua, Goringhaicona, the Gorachoqua, and the Cochoqua. The first war fought on March 1st in 1510 between the Portuguese and the Goringhaiqua is an historical moment of vastly unrecognized significance. Francisco De Almeida, the First Viceroy of the Portuguese State of India was defeated alongside his men by a Goringhaiqua force who deployed a unique and exemplary auxiliary unit, their cattle, to defeat the Portuguese. This close symbiotic relationship between the Khoi and nature is testimony to this feat. This battle resulted in the Portuguese not returning to the Cape of Good Hope for a century, but importantly prevented a future as a Portuguese slave colony. Slave history The first slaves deployed by the VOC were instated on Mostert farms of which the RiverClub forms part of. Here, the intermingling of the FreeBurghers, the Khoi with enslaved people from Java, Goa, Madagascar, Angola, who were mostly Muslim, saw the emergence of various mixed identities, and the etching of Afrikaans. The South African Astronomical Observatory right next to the River Club is a place where the Khoena gazed the stars and where the visual genius loci is unmistakable to the spiritual fortitude of our ancestors. The First and Final Frontier This is a battle of heritage protection, restorative justice, of a sacred confluence, at the site of the first frontier wars. It is about the genocidal menace of colonial invasion and ethnocide of Khoi and San. It also holds the beauty of what was before. This final frontier is a symbol of national restoration and reflection, an intangible myriad of memory that divides us as it unites us. It's time to pause, acknowledge, and restore. It is a nexus of the living history mankind, and is of National, Regional, and World Heritage significance. It is place of IGamirodi which in Khoekhoegowab means, 'a place where the stars gather".

Sea Point (Afrikaans: Seepunt) is an affluent and densely populated suburb of Cape Town, situated in the Western Cape, between Signal Hill and the Atlantic Ocean, a few kilometres to the west of Cape Town's Central Business District (CBD). Moving from Sea Point to the CBD, one passes first through the small suburb of Three Anchor Bay, then Green Point. Seaward from Green Point is the area known as Mouille Point (pronounced "mu-lee"), where the local lighthouse is situated. It borders to the southwest the suburb of Bantry Bay. It is known for its large Jewish population, synagogues, and kosher food options. Sea Point's positioning along the Cape Town coastline of the Atlantic Seaboard - from the Promenade to its wide variety of restaurants, has led to this neighbourhood being named as one of the most popular places in Cape Town to live in[2][3] or invest in,[4] with average property prices well above the median for the city.[5][6][7] In addition, Sea Point serves as a popular destination amongst tourists and visitors, being named by Time Out magazine as "one of the coolest neighbourhoods in the world" in 2022 and 2023.[8][9] Sea Point forms part of Ward 54 in The City Of Cape Town, and is represented by Democratic Alliance councillor Nicola Jowell.[10] The ratepayers, residents and local businesses in the area are represented by the Sea Point, Fresnaye & Bantry Bay Ratepayers and Residents Association (SFB), a volunteer-led organization financed by donations and memberships.[11] The SFB's mandate includes defending the heritage of the area,[12][13] construction applications,[14][15] providing added security and cleansing above what is provided by the City and State,[16][17][18] and communications with residents and ratepayers, as well as on behalf of these parties with stakeholders such as the City of Cape Town.[19][20][21] History Some of the first settlers in the area were the aristocratic Protestant Le Sueur family from Bayeux in Normandy. François Le Sueur arrived in 1739 as spiritual advisor to Cape Governor Hendrik Swellengrebel. The family's Cape estate, Winterslust, originally covered 81 hectares (200 acres) on the slopes of Signal Hill. The estate was later named Fresnaye, and now forms part of the suburbs of Sea Point and Fresnaye.[22] Sea Point got its name in 1767[23] when one of the commanders serving under Captain Cook, Sam Wallis, encamped his men in the area to avoid a smallpox epidemic in Cape Town at the time. It grew as a residential suburb in the early 1800s, and in 1839 was merged into a single municipality with neighbouring Green Point. The 1875 census indicated that Sea Point and Green Point jointly had a population of 1,425. By 1904 it stood at 8,839.[24] With the 1862 opening of the Sea Point tramline, the area became Cape Town's first "commuter suburb", though the line linked initially to Camps Bay. At the turn of the century, the tramline was augmented by the Metropolitan and Suburban Railway Company, which added a line to the City Centre.[25] During the 1800s, Sea Point's development was dominated by the influence of its most famous resident, the liberal parliamentarian and MP for Cape Town, Saul Solomon. Solomon was both the founder of the Cape Argus and the most influential liberal in the country—constantly fighting racial inequality in the Cape. His Round Church (St John's) of 1878 reflected his syncretic approach to religion—housing four different religions in its walls, which were rounded to avoid "denominational corners". "Solomon's Temple", as it was humorously known by residents, stood on its triangular traffic island at the intersection of Main, Regent, and Kloof roads, a centre of the Sea Point community, until it was destroyed by the city council in the 1930s.[26] The suburb was later classed by the Apartheid regime as a whites-only area, but this rapidly changed in the late 1990s with a rapid growth of Sea Point's black and coloured communities. Ships entering the harbour in Table Bay from the east coast of Africa have to round the coast at Sea Point and over the years many of them have been wrecked on the reefs just off-shore. In May 1954, during a great storm, the Basuto Coast (246 tonnes) ended up on the rocks within a few metres of the concrete wall of the promenade.[27] A fireman who came to the assistance of the crew was swept off the wall of the swimming pool adjacent to the promenade by waves and was never seen again. The vessel was soon thereafter salvaged for scrap. In July 1966 a large cargo ship, the S.A. Seafarer, was stranded on the rocks only a couple of hundred metres from the Three Anchor Bay beach. The stranding was the cause of one of Cape Town's earliest great environmental scares, owing to the cargo including drums of tetramethyl lead and tetraethyl lead, volatile and highly toxic compounds that in those days were added to motor fuels as an anti-knocking agent. The ship was gradually destroyed by the huge swells that habitually roll in from the south Atlantic. Salvage from the ship can still be found in local antique shops. The area was historically classed as a "whites only" area only during the apartheid era under the terms of the Group Areas Act, a series of South African laws that restricted urban areas according to racial classifications.[28] Some black and coloured residents continued to live in pockets of the suburb during this era.[29] The Twin Towers on Beach Road were built in the context of a "white housing crisis" in racially segregated Cape Town in the 1960s and 1970s. In the 1970s the National Party initiated several planning interventions, including the suspension of the city's zoning rules with regards to building height for developers willing to build housing in white Group Areas.[30] In the early 1970s, the iconic 23-storey Ritz Hotel was built in Sea Point, with a revolving restaurant.[31] Prior to the development of the V&A Waterfront, Sea Point was known as a "tiny Manhattan by the sea", known for its restaurants and entertainment.[32] In the mid to late 1990s, the area experienced a rise in crime as drug dealers and prostitutes moved into the area. However, due to the aggressive adoption of broken windows municipal management spearheaded by then area councillor Jean-Pierre Smith, the crime rate declined throughout most of the 2000s.[33] On the morning of 20 January 2003, nine men were killed in a brutal attack at the Sizzler's massage parlour in Sea Point.[34] -

Early map of Sea Point and its infrastructure, c. 1906 -

Cape 1st Class (4-4-0T) 1875 no. 4 -

Round Church or Solomons Temple, 1906 -

Graaff's Pool in 2020, shot on Kodak Ektar 100 Layout Sea Point beach with the beach front promenade Sea Point is a suburb of Cape Town and is situated on a narrow stretch of land between Cape Town's well known Lion's Head to the southeast and the Atlantic Ocean to the northwest. It is a high-density area where houses are built in close proximity to one another toward the surrounding mountainside. Apartment buildings are more common in the central area and toward the beachfront. An important communal space is the beachfront promenade, a paved walkway along the beachfront used for strolling, jogging, or socialising. Along the litoral of the Sea Point promenade, the coastline has varied characteristics. Some parts are rocky and difficult to access, while other parts have broad beaches. Sea Point beach adjoins an Olympic-sized seawater swimming pool, which has served generations of Capetonians since at least the early 1950s. Further toward the city is a beach known as Rocklands. Adjoining Sea Point is Three Anchor Bay. The beaches along this stretch are in the main covered with mussel shells tossed up by the surf, unlike the beaches of Clifton and Camps Bay, which are sandy. The rocks off the beaches at Sea Point are in large part late Precambrian metamorphic rocks of the Malmesbury formation, formed by low-grade metamorphism of fine-grained sediments. The site is internationally famous in the history of geology. A plaque on the rocks commemorates Charles Darwin's observation of the rare geological interface, where granite, an igneous rock, has invaded, absorbed, and replaced the Malmesbury formation rocks. There are extensive beds of kelp offshore. Compared to the False Bay side of the Cape Peninsula, the water is colder (11–16 °C). Graaff's Pool, a beachfront tidal pool partially demolished in 2005, was the subject of a short film entitled "Behind the Wall", which contrasted the pool's origin story of Lady Marais, paralysed from the waist down from childbirth, whose husband built the pool for her as a private bathing area in the 1930s, and the Sea Point gay scene, which adopted the pool as a cruising ground between the 1960s and the 2000s.[35] Transportation The suburb is served by the MyCiTi bus rapid transit system. The 108 and 109 services take passengers to Hout Bay, V&A Waterfront and Adderley Street in downtown Cape Town.[36] Houses of worship Marais Road Shul Jewish congregations Reform Jews living in the area are served by Temple Israel, an affiliate of the South African Union for Progressive Judaism, on Upper Portswood Road in neighbouring Green Point Christian congregations - Common Ground Church Sea Point meets at the same venue as Sea Point Congregational Church, a Christianchurch at the corner of Main Road and Marais Road

- Joshua Generation Church Sea Point, an Evangelical church that meets at Sea Point High School at 5 Norfolk Road[38]

- Life Church (part of the Assemblies of God movement), an Evangelical church on Main Road[39]

- Sea Point Evangelical Congregational Church, an Evangelical church on Main Road

- Sea Point Methodist Church, a Methodist church on Main Road

- Church of the Holy Redeemer, an Anglican church on Kloof Road

- St James the Great Anglican Church, an Anglican church on St James Road

- New Apostolic Church Sea Point, a New Apostolic church on Marais Road

- Our Lady of Good Hope Catholic Church (formerly St Francis Church), a Catholic church on the corner of St Andrews Road and Beach Road

Education Schools in the area include Sea Point Primary School and Sea Point High School (formerly Sea Point Boys' High School) founded in 1884,[40][41] and Herzlia Weizmann Primary. The French School of Cape Town opened on 14 October 2014[42] after an R18m upgrade of the primary school of the old Tafelberg Remedial School's campus.[43] The primary school campus of the French school is in Sea Point.[44] In popular culture - Life & Times of Michael K, a 1983 novel by J. M. Coetzee begins and ends in Sea Point.[45]

- Ah, but Your Land Is Beautiful, a 1983 novel by Alan Paton includes a description of Sea Point: "We are talking of fighting an election in Sea Point. It is probably one of the most favourable constituencies from our point of view, fairly affluent people with guilty consciences, a high percentage of Jewish voters, and a large number of retired business and professional men. There is probably a higher percentage of voters opposed to racial discrimination than anywhere else in South Africa."[46]

- Sea Point Days, a 2008 documentary film directed by François Verster[47]

Notable people Saul Solomon, Cape Town politician who resided in Sea Point for most of his life during the late 1800s. - John Whitmore, surfer, surfboard shaper, radio presenter, Springbok surfing team manager[48]

- Anthony Sher, actor and writer.

- David Bloomberg, mayor of Cape Town

- Sally Little, professional golfer.

- Saul Solomon, liberal Cape politician.

- Colin Eglin, politician.

- Gerry Brand, Springboks rugby union footballer.

- David Rosen, fashion designer and artist.

- Bob Newson, cricketer.

- Karen Press, poet.

- Jacobus Arnoldus Graaff, businessman and politician, bequeathed Graaff's Pool to the people of Cape Town.

- Louise Smit writer of popular South African television shows, Wielie Walie and Haas Das.

- Arno Carstens singer-songwriter.[49]

- Darrel Bristow-Bovey, writer[50]

Coat of arms The Green and Sea Point municipal council assumed a coat of arms in 1901.[51] The shield was divided vertically, one half depicting signal masts on Signal Hill, the other a golden lion's head, shoulders and forepaws; in the centre, near the top, was a small blue shield displaying three anchors. An imperial crown was placed above the shield.[52] The coat of arms has been incorporated into the emblem of the Metropolitan Golf Club[53] References - "Sub Place Sea Point". Census 2011.

- "Where to live in Cape Town". Expatica South Africa. Retrieved 2024-07-07.

- "Sea Point in Cape Town | Your Neighbourhood". 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2024-07-07.

- "Should you buy real estate in Sea Point?". The Africanvestor. 2023-12-13. Retrieved 2024-07-07.

- CBN (2023-05-15). "Sea Point emerges as a top destination for capital growth in Cape Town". Cape Business News. Retrieved 2024-07-07.

- "Sea Point Property Trends". Property 24.

- "Insights on 2023 South African Property Market Trends by BLOK's Jacques Van Embden". blogs.easyequities.co.za. Retrieved 2024-07-07.

- Holmes, Richard (20 October 2023). "Sea Point is one of the coolest neighbourhoods in the world". TimeOut.

- Sleith, Elizabeth (14 October 2022). "Sea Point, Cape Town, hailed as one of world's coolest neighbourhoods". Sunday Times.

- "City of Cape Town".

- "SFB Ratepayers & Residents Association". SFB Ratepayers and Residents Association. Retrieved 2024-07-06.

- "Heritage Project". SFB Ratepayers and Residents Association. Retrieved 2024-07-06.

- Joseph, Shahied (16 May 2024). "SFB want holistic approach to development". The Atlantic Sun.

- "Planning Committee". SFB Ratepayers and Residents Association. Retrieved 2024-07-06.

- "Laughtons Hardware closes down after 104 years". The Cape Argus. 28 June 2024.

- "Safety & Cleaning Initiative". SFB Ratepayers and Residents Association. Retrieved 2024-07-06.

- "How can I humanely get homeless people sleeping outside my house to move?". GroundUp. 8 March 2024.

- Yuku, Nomzamo (30 July 2022). "Project Homeless Outreach Prevention and Education gives beneficiaries a second chance". The Weekend Argus.

- "Communications". SFB Ratepayers and Residents Association. Retrieved 2024-07-06.

- "Local property owners urged to object valuations". Cape Town Etc. 17 April 2019.

- SFB (2023-11-30). "Helicopters Along the Atlantic Seaboard". SFB Ratepayers and Residents Association. Retrieved 2024-07-06.

- Green, L. (1964). "Sea Point was a Paradise". I Heard the Old Men Say. Cape Town: Howard Timmins – via Internet Archive.

- "Wallis, Samuel".

- sahoboss (2011-07-14). "Sea Point". South African History Online. Retrieved 2018-06-17.

- "Sea Point: On the Boardwalk". Archived from the original on 2013-04-21. Retrieved 2013-03-18.

- Green, L. (1964). "Tower and Bells". I Heard the Old Men Say. Cape Town: Howard Timmins.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-10-20. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- "Pain, shock of forced removals".

- Winning vibes – see in photos why Sea Point was just named one of world’s coolest neighbourhoods Daily Maverick. 17 October 2022

- Building an icon: Disi Park Visi. 13 March 2023

- Sea Point welcomes the return of The Ritz Biz Community. 5 December 2017

- Lategan, Herman (2023). Son of a Whore: A memoir. Cape Town: Penguin Books. p. 37. ISBN 9781776391240.

- Witness - Battle of Sea Point. Al Jazeera. January 15, 2009. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13.

- "Sizzlers massacre remains a mystery | IOL News". Retrieved 2018-06-17.

- Ronan Steyn (2012-09-10), Behind The Wall - In Zero Short Film Competition Winner 2012, archived from the original on 2021-12-13, retrieved 2018-06-17

- MyCiTi System Map Accessed on 12.9.2023

- Mandela Visits Cape Town Shul and Reassures Jews on Their Future Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 10 May 1994

- "Joshua Generation Sea Point". Joshua Generation Churches.

- "Life Church Sea Point". Assemblies of God Group.

- "Apache2 Ubuntu Default Page: It works". www.spps.wcape.school.za.

- Botha, P (March 2014). "Sea Point High School – 130th Birthday: Established 21 April 1884". The Good Times. 2 (1): 16. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- "French School opens New Campus in Sea Point" (Archive). Orange South Africa. Retrieved on 22 January 2015.

- McCain, Nicole. "SEA POINT WELCOMING THE FRENCH." People's Post. 13 February 2014. Retrieved on 22 January 2015.

- "CONTACT." Cape Town French School. Retrieved on 22 January 2015. "Lycée Français du Cap 101, Hope Street - Gardens 8001 Cape Town South Africa" and "Ecole Française du Cap Corner Tramway and Kings road - Sea Point 8005 Cape Town South Africa"

- Coetzee, J.M. Life & Times of Michael K. Ravan Press 1983

- Paton, Alan. Ah, but Your Land is Beautiful. Penguin Books. 1983. pp. 103-104.

- "Sea Point Days". Sundance Channel. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- "The John Whitmore Book Project". The John Whitmore Book Project.

- "Carstens Considers Us". Channel. Retrieved 2018-06-17.

- "In praise of Sea Point | Darrel Bristow-Bovey". www.randomreads.co.za. Retrieved 2018-06-17.

- Western Cape Archives : Green and Sea Point Municipal Minutes (10 July 1901).

- Murray. M. (1964). Under Lion's Head.

- "Metropolitan - Golf Course". www.metropolitangolfclub.co.za.

External links Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sea Point.

Pinelands is a garden city suburb located on the northern edge of the southern suburbs of Cape Town, South Africa, neighbouring the suburb of Thornton, and is known for its large thatched houses and green spaces. The suburb is primarily residential and is often praised for its peacefulness and abundance of trees. Pinelands is one of the few areas in Cape Town in which sale of alcohol to the public is prohibited, but some clubs have private liquor licenses. It is a popular place for senior citizens to retire to. While there are several retirement homes in the suburb, younger people are increasingly moving in. The main road is called Forest Drive and the suburb contains two small shopping centres, namely Howard Centre (named after Ebenezer Howard who led the garden city movement) and Central Square. Dutch Reformed, Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist and Catholic (Society of St. Pius X) churches are located near to Central Square, while Baptist, Church of England in South Africa and mainstream Catholic churches are located elsewhere in the suburb. Pinelands is served by two Metrorail railway stations: Pinelands station on the western edge of the suburb and Mutual station on the northern edge. The suburb is bisected from the north east to the south west by the Elsieskraal River, which has flowed through a large concrete drainage canal since the 1970s. Elsieskraal River also flows through the neighbouring suburb of Thornton, which is a similar residential suburb with an abundance of trees. The postcodes for Pinelands are 7405 for street addresses and 7430 or 7450 for post office boxes. The telephone exchange codes for Pinelands are predominantly 531 and 532 (within the 021 dialling code for Cape Town). History Old postbox in The Mead. The layout of Pinelands is based on the then revolutionary Garden Cities methodology of town planning by the British town-planner, Sir Ebenezer Howard. It was originally a Victorian era farm named Uitvlugt that had thousands of pine trees planted in it, and was later deemed an economic failure by the Department of Forestry. In the aftermath of the outbreak of the bubonic plague in Cape Town in February 1901, the colonial health authorities invoked Public Health Act of 1897 and quickly established a location in Uitvlugt forest station (modern day Pinelands). Black Africans living in District Six were rounded up under armed guard and taken to the location of Uitvlugt. This area was initially established primarily to quarantine Black Africans who were forcibly relocated after the outbreak of the disease, furthering efforts of the government at the time to push Black and Coloured communities to the outskirts of the city. This marked the beginning of forced removals in Cape Town in the twentieth century. Almost 22 years later, the land was then granted to "The Garden Cities Trust" and the founding Deed of Trust was signed in 1919. One of the first members of the trust, Richard Stuttaford (head of the department store Stuttafords), made a £10,000 gift donation to serve as capital, and a loan of £15,000 from the government was invested in Pinelands. The trust brought in an overseas expert, Albert John Thompson, in 1920 to design the area. The first (thatched) house in Pinelands to be occupied was 3 Mead Way and was built in February 1922. The house and entire street, including The Mead were declared a national monument in 1983. The original township area is currently a proposed heritage area. Pinelands converted to a municipality in 1948 and in 1996 merged into the City of Cape Town metropolitan municipality. The old Pinelands Town Council offices now accommodate the Pinelands Subcouncil. Demographics According to the 2011 census, the population of Pinelands was 14,198 people in 4,917 households. The following tables show various demographic data about Pinelands from that census.[2] - Gender

Gender Population % Female 7,596 53.5% Male 6,602 46.5% - Ethnic Group

Group Population % Black African 1,917 13.5% Coloured 2,142 15.1% Indian/Asian 720 5.1% White 8,845 62.3% Other 574 4.0% - Home Language

Language Population % English 10,868 81.5% Afrikaans 1,125 8.4% Xhosa 470 3.5% Other SA languages 297 2.2% Other languages 568 4.3% - Age

Age range Population % 0–4 805 5.7% 5–14 1,517 10.7% 15–24 2,023 14.3% 25–64 7,508 52.9% 65+ 2,343 16.5% Politics Pinelands is part of ward 53 of the City of Cape Town.[3] The ward also includes Thornton, Maitland Garden Village, Epping Industria 1, Ndabeni and part of Maitland; the current ward councillor is Riad Davids of the Democratic Alliance.[4] Of the six voting districts in this ward, three of them cover Pinelands: the voting stations are at the Pinelands Primary School, Pinelands High School, and Pinehurst Primary School. Generally, the majority of voters in the Pinelands area of the Ward vote for the Democratic Alliance. The following tables show the sum of the votes cast in the three Pinelands voting districts at the most recent national, provincial and local elections. - National election (2019)

Party Votes % Democratic Alliance 5,492 74.7% African National Congress 894 12.2% African Christian Democratic Party 295 4.0% Good 146 2.0% Economic Freedom Fighters 143 1.9% 26 other parties 386 5.2% Total 7,356 100% - Provincial election (2019)

Party Votes % Democratic Alliance 5,892 80.4% African National Congress 513 7.0% Good 288 3.9% African Christian Democratic Party 207 2.8% Economic Freedom Fighters 130 1.8% 22 other parties 298 4.1% Total 7,328 100% - Local election (2021)

Proportional Representation vote Party Votes % Democratic Alliance 4,658 81.0% Good 314 5.5% African Christian Democratic Party 196 3.4% African National Congress 164 2.9% 46 other parties 41.8 7.3% Total 5,750 100% - Local election (2021)

Ward vote Candidate Votes % Riad Davids (DA) 5,145 82.7% Ingrid Simons (Good) 269 4.3% Richard Bougard (ACDP) 248 4.0% Brenda Skelenge (ANC) 192 3.1% 30 other candidates 368 5.9% Total 7,122 100% Road names Many of the road names in Pinelands have originated from local history or from places in England. One such road is named Uitvlugt (original Dutch) after the historical farm of the same name that covered what is now Pinelands. There are also roads named Letchworth and Welwyn after the first two garden cities in England. Other roads in Pinelands are named after places in the Lake District in England, the Royal Family as well as the names of birds, trees and flowers. Curiously, despite the attitude displayed to the sale of alcohol in Pinelands, there is a section where all the roads are named after well known wine farms. Schools In Pinelands there are three public primary schools, each of which is commonly known in the community by a colour: Pinelands Primary School ("The Blue School"), Pinelands North Primary School ("The Red School") and Pinehurst Primary School ("The Green School"). Pinelands High School is a public high school, centrally located in the suburb. Cannons Creek Independent School is a private combined primary and high school. Grace Primary School is a Christian primary school embracing a Charlotte Mason education philosophy.[5] There are three private pre-primaries in Pinelands: Meerendal Pre-Primary, La Gratitude Pre-Primary, Learn and Play Centre Pre-School and Old Mutual for their employees. The high school campus of Vista Nova (a school for children with cerebral palsy and other special needs) is located in the suburb. The Pinelands Campus of the College of Cape Town while located in Maitland is on the northern edge of Pinelands and draws students from all over Cape Town. Sports Pinelands has sporting facilities including tennis and lawn bowling clubs. Other sports include the cricket and hockeyclubs situated at The Oval sports grounds situated on St. Stephens Road just off Forest Drive. Pinelands hockey club was founded in 1937 and is currently one of the largest clubs in the country fielding 12 men’s teams and 7 ladies teams in the Western Province Hockey Union league. Both the men’s and ladies’ first teams play in the Grand Challenge league with the men's team having won the title for the first time in 2006. In 2008 Pinelands Hockey Club produced three Olympians – Marvin Bam, Paul Blake and Austin Smith. Austin Smith was made the South African Men's Captain, having first played hockey for the Red School and the Pinelands High School. Coat of arms Coat of arms of Pinelands In January 1949, the municipal council assumed a coat of arms, designed by F. de Beaumont Beech.[6] It registered the arms with the Cape Provincial Administration in July 1954[7] and at the Bureau of Heraldry in July 1979.[8] The arms were : Or, on a chevron Gules, between three fir-cones Sable, slipped and leaved Vert, three annulets Or (i.e. a golden shield depicting, from top to bottom, two black fir-cones with green leaves, a red chevron displaying three golden rings, and another black fir-cone with green leaves). The crest was a squirrel holding an acorn, and the motto was Fides – prudentia – labor. See also References External links