Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

June 11, 2024 3:19 AM

|

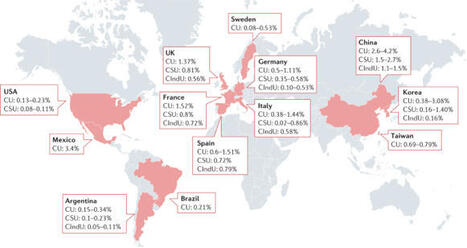

Urticaria is an inflammatory skin disorder that affects up to 20% of the world population at some point during their life. It presents with wheals, angioedema or both due to activation and degranulation of skin mast cells and the release of histamine and other mediators. Most cases of urticaria are acute urticaria, which lasts ≤6 weeks and can be associated with infections or intake of drugs or foods. Chronic urticaria (CU) is either spontaneous or inducible, lasts >6 weeks and persists for >1 year in most patients. CU greatly affects patient quality of life, and is linked to psychiatric comorbidities and high healthcare costs. In contrast to chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), chronic inducible urticaria (CIndU) has definite and subtype-specific triggers that induce signs and symptoms. The pathogenesis of CSU consists of several interlinked events involving autoantibodies, complement and coagulation. The diagnosis of urticaria is clinical, but several tests can be performed to exclude differential diagnoses and identify underlying causes in CSU or triggers in CIndU. Current urticaria treatment aims at complete response, with a stepwise approach using second-generation H1 antihistamines, omalizumab and cyclosporine. Novel treatment approaches centre on targeting mediators, signalling pathways and receptors of mast cells and other immune cells. Further research should focus on defining disease endotypes and their biomarkers, identifying new treatment targets and developing improved therapies. Urticaria is an inflammatory skin disorder that presents with itchy wheals and/or angioedema mediated by skin mast cells and release of histamine and other mediators. This Primer by Kolkhir et al. summarizes the epidemiology, mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment of urticaria, and discusses patient quality of life and open research questions for this condition.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

January 7, 2022 3:30 AM

|

Abstract This update and revision of the international guideline for urticaria was developed following the methods recommended by Cochrane and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development...

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

January 20, 2021 4:38 AM

|

Home: Reviews & News: Medical Journal Reviews: 2021: January 2021 Medical Journal Review January 2021 WAO Reviews – Editors' Choice Articles are selected for their importance to clinicians who care for patients with asthma and allergic/immunologic diseases by Juan Carlos Ivancevich, MD, and John J. Oppenheimer, MD - FACAAI - FAAAAI, WAO Reviews Editor. Asthma and COVID-19: Do we finally have answers? Eger K, Bel EH European Respiratory Journal 2020; in press https:/doi.org/10.1183/13993003.04451-2020 In this paper, Eger and Bel explore the impact of asthma on COVID 19. While it is well known that older age, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes are risk factors of poor COVID-19 outcome, much controversy surrounds asthma’s impact. The focus of this manuscript was 2 papers published in the same edition of the ERJ (Choi et al and Izquierdo et al). In summary, these large-scale studies confirmed previous findings regarding risk for asthma patients to develop (severe) COVID-19 – specifically that asthmatics appear to be slightly more susceptible to contracting COVID-19, but severe disease progression does not seem to be related to medication use, including asthma biologics, but rather linked to older age and co-morbidities. The authors stress the fact that often when examining studies of COVID-19 and asthma, potential bias factors have not been considered, leaving many questions unanswered. Furthermore, large-scale, multinational real-life studies with detailed information on asthma phenotype and medication usage in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 would be ideal to aid us in resolving these questions. The Metabolomics of Childhood Atopic Diseases: A Comprehensive Pathway-Specific Review Schjødt MS, Gürdeniz G, Chawes B Metabolites 2020;10(12):511 https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo10120511 Asthma, allergic rhinitis, food allergy, and atopic dermatitis are common childhood diseases with several different underlying mechanisms, i.e., endotypes of disease. In this review, the authors stress that metabolomics has the potential to identify disease endotypes, which could beneficially promote personalized prevention and treatment. They do a wonderful job of reviewing the metabolomics literature in children with atopic diseases, focusing on tyrosine and tryptophan metabolism, lipids (particularly, sphingolipids), polyunsaturated fatty acids, microbially derived metabolites (particularly, short-chain fatty acids), and bile acids. Specifically, tyrosine, 3-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, N-acetyltyrosine, tryptophan, indolelactic acid, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, p-Cresol sulfate, taurocholic acid, taurochenodeoxycholic acid, glycohyocholic acid, glycocholic acid, and docosapentaenoate n-6 were identified in at least two studies as being impactful. They stress that altered metabolic pathways highlight some of the underlying biochemical mechanisms leading to these common childhood disorders, which in the future could provide utility in clinical practice. Much further work on this topic is still needed. Helicobacter pylori and skin disorders: a comprehensive review of the available literature Guarneri C, Ceccarelli M, Rinaldi L, Cacopardo B, Nunnari G, Guarneri F European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2020;24(23):12267-12287 https://www.doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202012_24019 Helicobacter pylori is a Gram-negative bacterium identified for the first time about 30 years ago and commonly considered as the main pathogenic factor of gastritis and peptic ulcer. Since then, it was found to be associated with several gastrointestinal and extra-gastrointestinal diseases, including skin disorders such as chronic urticaria, rosacea, lichen planus, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, pemphigus vulgaris, vitiligo, primary cutaneous MALT-type lymphoma, sublamina densa-type linear IgA bullous dermatosis, primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphomas, and cutaneous T-cell pseudolymphoma. The aim of this review is to summarize the available studies regarding the topic and draw possible conclusions. The authors found that, overall, further clinical and laboratory studies are needed to assess the real plausibility and relevance of these associations, as well as the possible role of Helicobacter pylori with the underlying pathogenic mechanisms. Allergy prevention: An overview of current evidence Royal C, Gray C Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 2020;93(5):689-698 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7757062/ There has been a rapid rise in allergic disorders worldwide, which has resulted in increased research into the determinants of allergy development in attempt to identify factors that may be manipulated to mitigate risk. Present literature demonstrates that an opportune window in immunological development appears to exist in early life, whereby certain exposures may promote or prevent the development of an allergic disposition. Furthermore, factors that affect the composition and diversity of the microbiome in early life may also be impactful. In this review, the authors explore the current literature and recommendations relating to exposures that may prevent allergy development or promote tolerance. They note several risk factors, including delivery by caesarean section, omission of breastfeeding, vitamin D insufficiency, and environmental exposures, such as cigarette smoke exposure, all increase the risk of an allergic predisposition. Likewise, they note several protective factors, including dietary diversity during pregnancy, lactation, and in infancy is protective. They also note that recommendations for food-allergen exposure have shifted from delayed introduction to early introduction as a tolerance-inducing strategy. Supplements such as probiotics and vitamins during pregnancy and infancy have yet to produce conclusive results for allergy prevention. Finally, they note that emollient use in infancy has not been shown to be protective against eczema or food allergy. The airways microbiome of individuals with asthma treated with high and low doses of inhaled corticosteroids Martin MJ, Zain NMM, Hearson G, Rivett DW, Koller G et al PLoS One 2020;15(12):e0244681 https://www.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244681 Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the mainstay of asthma treatment, but evidence suggests a link between ICS usage and increased rates of respiratory infections. In this study, Martin and colleagues assessed the composition of the asthmatic airways microbiome in patients taking low and high dose ICS and the stability of the microbiome over a 2-week period. Sputum from each subject underwent DNA extraction, amplification and 16S rRNA gene sequencing of the bacterial component of the microbiome. Nineteen subjects returned for further sputum induction after 24 h and 2 weeks. A total of 5,615,037 sequencing reads revealed 167 bacterial taxa in the asthmatic airway samples, with the most abundant being Streptococcus spp. No significant differences in sputum bacterial load or overall community composition were seen between the low- and high-dose ICS groups; however, Streptococcus spp. showed significantly higher relative abundance in subjects taking low-dose ICS (p = 0.002). Furthermore, Haemophilus parainfluenzae was significantly more abundant in subjects on high-dose fluticasone propionate compared to those on high-dose budesonide (p = 0.047). There were no statistically significant changes in microbiota composition over a 2-week period. The authors note that the clinical implications for patients are not known, but suggest that this does provide a possible explanation for the increased risk of pulmonary infection seen in asthma and COPD, particularly with FP. More research is needed.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

July 4, 2020 2:35 AM

|

Abstract Background Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is considered an autoimmune disorder in 50% of cases at least, in which T‐ and mast cell mediators are considered to be the primary cause of ...

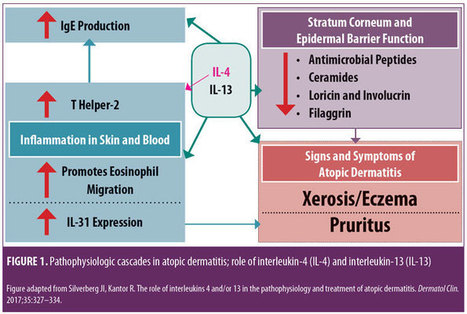

Monoclonal Antibody Therapies for Atopic Dermatitis: Where Are We Now in the Spectrum of Disease Management? JCAD Online Editor | February 1, 2019 This ongoing column explores emerging treatment options, drug development trends, and pathophysiologic concepts in the field of dermatology. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(2):39–43 by James Q. Del Rosso, DO Dr. Del Rosso is Research Director of JDR Dermatology Research in Las Vegas, Nevada; is with Thomas Dermatology in Las Vegas, Nevada; and is Adjunct Clinical Professor (Dermatology) with Touro University Nevada in Henderson, Nevada. FUNDING: There was no funding related to the development, writing, or publication of this article. DISCLOSURES: Dr. Del Rosso is a consultant, speaker, and/or researcher for several companies who market products used in the management of atopic dermatitis or have compounds under development. These include Almirall, Dermira, Galderma, Genentech, LaRoche Posay, Leo Pharma, Loreal, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, Promius, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme, Skinfix, Sonoma, Sun Pharma, and Taro. Abstract: Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic disorder that requires thorough patient education and a therapeutic management strategy designed to control flares, decrease recurrences, and reduce pruritus. In cases that cannot be controlled by proper skin care and barrier repair, topical therapy, and avoidance of triggers, systemic therapy is often required to control flares and maintain remission. It is important for clinicians to avoid becoming overly dependent on the intermittent use of systemic corticosteroid therapy to control flares, without incorporating other treatment options that might more optimally control AD over time. This article provides an overview of systemic therapies, including conventional oral therapy options and injectable biologic agents, that modulate the immune dysregulation in AD. Major emphasis is placed on the monoclonal antibodies currently available (e.g., dupilumab) for the treatment of AD, as well as those in latter stages of development, with a focus on agents targeting IL-4 and/or IL-13. KEYWORDS: Atopic dermatitis, calcineurin inhibitors, phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors, immunosuppressants, interleukin-4, interleukin-13 Many patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) are able to control their disease primarily with topical agents, including corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitors, moisturizers/barrier repair agents, wet wraps, and the avoidance of triggers.1,2 However, it is important to better define the word “control,” as AD is a chronic disorder characterized by marked flares of eczema and pruritus, variable periods of persistent eczema of lesser severity with itching, and complete remission, all of which vary in intensity, frequency, and duration among each individual affected by AD. Marked flares can often be mitigated with topical agents of adequate potency and duration, and, in selected cases, in conjunction with short courses of systemic corticosteroid (CS) therapy. The most difficult therapeutic challenges in AD are effective control of eczematous dermatitis (eczema) and pruritus, both of which are persistent but of a lesser overall severity, and the maintenance of remission after control of disease flares.1–5 Many patients with AD, including the parents/guardians of children with AD, deserve a discussion of what options exist beyond topical management alone and intermittent systemic CS therapy. This discussion often needs to be initiated by the clinician, as patients with AD or other chronic disorders depend on their clinician to direct them toward what is likely to be the most effective treatment for them at any given point in time. There are only so many oral CS courses or intramuscular CS injections a clinician can prescribe to help control AD flares without tipping the benefit versus risk balance toward too much risk. This same principle also applies to repeated use of topical CS therapy, which can progress to use so frequent that the risk for adverse effects is increased significantly. Skin barrier repair agents and steroid-sparing topical agents (e.g., pimecrolimus, tacrolimus, crisaborole) provide marked benefit in some cases of AD, especially on certain anatomic sites or when the affected body surface area (BSA) is not too extensive.1–3 However, most patients with AD would benefit from systemic therapies that are designed to achieve optimal suppression of AD, including eczematous dermatitis and/or pruritus. Daily diffuse application of a well-formulated moisturizer for skin barrier maintenance and the application of prescription topical therapies to persistent AD lesions remain part of the standard therapeutic regimen, especially for localized refractory and lichenified sites.1–6 Finding the optimal balance of therapeutic choices varies among individual patients and requires careful consideration of the overall clinical situation and specific patient-related factors, such as age, severity of AD signs and symptoms, and patient and clinician comfort levels with the treatments selected. Ultimately, the clinician should identify what is most likely to achieve an optimal level of control and express their treatment recommendations to the patient with realistic confidence and a proper benefit versus risk discussion. The time has come for clinicians treating AD to consider moving from a rescue approach for flares to treating AD as a chronic, inflammatory, cutaneous and systemic disorder by using therapies that more selectively suppress the underlying disease pathophysiology, effectively treat eczema and pruritus, mitigate flares, and sustain long-term control of the disease. While topical therapies to manage epidermal barrier dysfunction and inflammation of AD should remain an important component of the total management approach for patients with AD, clinicians would be prudent to also consider therapies with better short-term and long-term safety profiles than the conventional oral agents that are currently available. In this article, an overview of the current conventional oral systemic therapeutic options for atopic dermatitis are presented, followed by an overview of the new systemic therapeutic options for AD, namely monoclonal antibody agents, including the currently available agent, duplimab, and other agents in latter stages of development, with a focus on compounds targeting IL-4 and/or IL-13. Other monoclonal antibodies that have been studied and/or are currently under evaluation for treatment of AD, such mepolizumab (anti-IL-5), nemolizumab (anti-IL-31), and omalizumab (anti-IgE), as well as other drug classes, will be discussed in future installments of “What’s New in the Medicine Chest.” Conventional Systemic Therapeutic Options for Atopic Dermatitis—Oral Agents When patients with moderate-to-severe AD and their clinicians are considering systemic therapy for AD, a variety of treatment options are available.3,5–12 Prior to 2018, available systemic therapies for AD were primarily oral agents, such as cyclosporin, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil, all of which appear to modulate the underlying pathophysiologic pathways that contribute to AD.3,6–8 Each of these agents has variable amounts of data available regarding its use in children and adults for treatment of AD.3,6–12 However, none of these oral agents are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of AD, and all exhibit immunosuppressant properties.3,8 Oral antihistamines have also been used as part of the treatment regimen for AD, primarily as an adjunctive therapy to help reduce pruritus and/or decrease interference with sleep (i.e., sedating antihistamines).12 It is important to note that chronic or frequent use of systemic CS is best avoided in children and adults due to the risk of several significant AEs.6,10–12 Cyclosporin. Among the conventional systemic oral agents used in the management of AD, cyclosporin appears to exhibit the fastest onset of efficacy, but its use is limited by its safety profile, which includes risks of nausea, cephalgia, hypertension, nephrotoxicity, sequelae of chronic immunosuppression, gingival hyperplasia, and drug interactions.6,8,10 Cyclosporin is primarily recommended for treatment-resistant and/or uncontrolled AD, after which patients are usually transitioned to a safer, long-term approach; continuous use of cyclosporin beyond 12 to 24 months generally is not advisable.6,8,10 Methotrexate. Methotrexate therapy, another conventional systemic oral treatment for AD, can exhibit efficacy in as little as 4 to 8 weeks, but, like cyclosporin, warrants careful monitoring due to potential adverse events (AEs); these include nausea, bone marrow suppression (including pancytopenia), hepatotoxicity, pulmonary fibrosis, potential sequelae of immunosuppression, drug interactions, and the need to avoid alcohol intake.6,8,10 As with cyclosporin, long-term use of methotrexate should likely be avoided. Azathioprine. Azathioprine is another conventional systemic oral treatment option for AD, but it is not usually considered an initial systemic option due to its slower onset of efficacy and potential toxicities. Potential AEs include bone marrow suppression, increased malignancy risk, other sequelae of immunosuppression, severe nausea/vomiting, abdominal pain, hepatotoxicity, drug hypersensitivity syndrome, and risk for drug-drug interactions (e.g., allopurinol).6,8,10 Mycophenolate mofetil. Finally, although data for use of mycophenolate mofetil as a treatment option for AD are more limited than cyclosporin data, mycophenolate mofetil appears to be the safest oral agent, when compared with cyclosporin, methotrexate, and azathioprine; it has an efficacy onset range of 4 to 12 weeks, making it a logical choice when transitioning patients to longer-term oral maintenance therapy after initial use of cyclosporin for treatment-refractory or severe AD. Potential AEs include gastrointestinal side effects, fatigue, hematologic changes, and potential sequelae of immunosuppression.6,8,10 Biologics for Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis Research is in progress evaluating a variety of injectable and/or oral agents, including PDE4 inhibitors, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, cannabinoid receptor agonists, kappa-opioid receptor agonists, and agents that target thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP).14–17 A systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies evaluating the efficacy of biologics in AD treatment (published in April 2018) reported good evidence, to date, regarding agents that inhibit IL-4 and/or IL-13; a relative lack of evidence supporting efficacy in AD was noted thus far in studies with biologics modulating other targets, such as omalizumab (anti-IgE), infliximab ((anti-tumor necrosis factor), ustekinumab (anti-IL-12/23), and rituximab (anti-B-cell).19 IL-4 and IL-13 are reported to play prominent roles in AD with inflammation in skin and/or blood, epidermal barrier impairment, pruritis, and susceptibility to infection (Figure 1).18 Monoclonal antibodies that inhibit the effects of various ILs (i.e., IL-4, IL 13, IL-5, IL-17, IL-22, IL-31, IL-33) are showing therapeutic promise for the treatment of AD. Monoclonal Antibody Interleukin-4 and Interleukin-13 Inhibitor Dupilumab. Dupilumab is an injectable human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 cytokine responses, including the expression and/or release of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and IgE; binding of dupilumab occurs with both Types I and II IL-4 alpha receptors, found on hematopoietic cells and keratinocytes, respectively.13,20,21 In March 2017, duplimab was FDA-approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD in adult patients (aged ?18 years) in whom the disease has not been adequately controlled with prescription topical therapies or in cases where such therapies are not advisable. In October 2018, duplimab was also approved as an add-on maintenance treatment in adolescent and adult patients (aged ?12 years of age) for moderate-to-severe asthma with an eosinophilic phenotype or oral–corticosteroid-dependent asthma.13 13 The dosing regimens for AD and asthma might differ between patients; however, the common regimen includes a 600mg loading dose (2×300mg2/mL injections), followed by a single 300mg injection every two weeks; with regard to asthma, dupilumab is not indicated or recommended for relief of acute bronchospasm or status asthmaticus.13 Clinical response. In the pivotal randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating dupilumab for AD, which included a Phase II, dose-ranging study, two 16-week monotherapy RCTs versus placebo, and a 52-week RCT that allowed for combination use with a topical CS, 1,472 subjects received dupilumab, with 739 treated for more than 52 weeks.13,20–22 Efficacy was substantiated by improvements in several assessment parameters versus placebo, both clinically and statistically, including positive changes in Investigator Global Assessment (IGA), marked reductions in Eczema Area Severity Index (EASI) scores, and significant decreases in pruritus, with clinical improvements sustained in the 52-week study without any loss of efficacy.13,20,21 Many patients reported a definite improvement in eczema and pruritus within the first few injections of dupilumab; however, onset of efficacy occurred later in some individuals (within 2 to 3 months after starting therapy). In patients currently undergoing other systemic therapies for severe AD (e.g., cyclosporin, methotrexate) who are starting dupilumab, researchers recommended that therapy be bridged without abrupt discontinuation of the patients’ previous therapy in order to avoid rebound exacerbation of AD while waiting for the clinical effects of dupilumab to manifest. Clinicians should then determine, on a case-by-case basis, the optimal approach to take when tapering patients off previous systemic therapy. 13,20–22 Safety. During the RCTs, no significant changes occurred in laboratory test results of the study subjects; thus, laboratory monitoring was not required by the FDA to be included in the approved product labeling for dupilumab.13 The most common AEs observed in the RCTs were injection site reactions and conjunctivitis (10–16% in active arms vs. 2–9% in placebo arms); separately, hypersensitivity reactions (e.g., urticaria, serum sickness-type reactions) were observed in less than one percent of the active-treatment study subjects.13,20–22 Most cases of conjunctivitis did not require stopping dupilumab, and were treated with topical ophthalmic lubricants and anti-inflammatory agents, and appeared to resolve or markedly improve despite continued use of the drug; however, some cases were severe enough to require discontinuation of dupilumab therapy.13,20–23 New onset or worsening ocular symptoms warrant referral to an ophthalmologist for evaluation.13,23 Ocular abnormalities inherent to AD that are unrelated to dupilumab use, including conjunctivitis and blepharitis, are not uncommon; the cause of the conjunctivitis that occurs related to use of dupilumab is not fully understood.24 Dupilumab and concomitant systemic therapy. A complete review of publications on dupilumab are beyond the scope of this article; however, a few articles provide information on the effective and safe use of dupilumab in a subpopulation of patients previously treated with cyclosporin. In a 16-week RCT study of adults with AD (N=390), responses to dupilumab therapy in conjunction with a medium-potency topical CS were assessed in subjects with inadequate response to or intolerance of oral cyclosporin or those in whom it was clinically inadvisable to use cyclosporin.25 Researchers reported that, following individual clinical assessment, topical CS therapy was safely tapered and/or stopped in many patients. Results of the study indicate that dupilumab with concomitant topical CS therapy (when needed) might signi?cantly improve signs and symptoms of AD and patient quality of life, with no new safety signals noted by the investigators.25 Infection risk. Eight RCTs that assessed outcomes with dupilumab versus placebo in patients with AD were analyzed by meta-analysis, with an emphasis on the incidence of AEs.26 Regarding infection rate risks, dupilumab had a lower risk of skin infection (risk ratio: 0.54), compared with placebo, with similar to negligible risks noted for nasopharyngitis, urinary tract infection, upper respiratory tract infection, and herpes virus infection. These observations further support the concept that dupilumab is immunomodulatory through the mitigation of IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, without a significant increased risk of infection, which can occur with immunosuppressive agents. It is important to note that by counteracting certain immune dysfunctions that lead to epidermal barrier impairment and cascades of Th2-driven humoral and cutaneous inflammation, dupilumab might help to normalize certain immunologic processes that are dysregulated in AD. Continued research and pharmacovigilance will help elucidate the efficacy and safety factors associated with dupilumab in greater detail. Monoclonal Antibody Interleukin-13 Inhibitors Lebrikizumab. Lebrikizumab is an injectable monoclonal antibody that exhibits high-affinity binding to soluble IL-13, thus preventing pro-inflammatory signaling by inhibiting heterodimerization of the IL-13 alpha/IL-4 alpha complex.27 In a preliminary Phase II, dose/frequency-ranging 12-week RCT, 209 adults with moderate-to-severe AD were treated with one of three dosing regimens of active drug versus placebo. Following a two-week “run in” with medium-potency topical CS therapy (triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% applied twice daily with lower potency hydrocortisone 2.5% allowed for facial AD), patients were randomized to receive lebrikizumab 125mg every four weeks, a single dose of lebrikizumab (125mg or 250mg), or placebo. Primary efficacy endpoint was the percent of subjects achieving a 50-percent reduction in EASI at Week 12.27 Investigators reported that patients in the lebrikizumab 125mg every four weeks achieved markedly superior results compared with those in the single-dose lebrikizumab group and those in the control group. Superiority to placebo was also observed in other parameters (e.g., SCORAD-50, reduction in BSA). An increasing trajectory of favorable response based on the EASI-50 results was noted at the end of the study (12 weeks) in the group receiving lebrikizumab 125mg every four weeks. Overall, the safety profile was favorable in all study arms.27 Data from this early study in AD suggest that lebrikizumab for AD shows promise as a treatment for AD. Additional research is needed on whether further increases in the dose per injection or treatment frequency (i.e., interval between doses) and use of a loading dose improve lebrikisumab’s efficacy, without affecting safety, for initial and maintenance therapy for AD. Tralokinumab. Tralokinumab, an IgG4 human monoclonal antibody that specifically neutralizes IL-13, was evaluated in a Phase IIb, dose-ranging, 12-week RCT of adult subjects (N=202) with moderate-to-severe AD.28,29 Patients were randomized to receive a 45mg (n=50), 150mg (n=51), or 300mg (n=51) subcutaneous injection of tralokinumab or placebo (n=50) every two weeks after a two-week “run in” with a mid-strength topical CS.29 Several efficacy parameters were assessed, with the coprimary endpoints being the change from baseline in total EASI score at Week 12 and the percent of IGA responders at Week 12 versus baseline (IGA score of clear/almost clear + at least a 2-grade reduction). Overall, AEs were generally similar among all study arms. Interestingly, six of the 204 subjects (2.9%) exhibited treatment-emergent conjunctivitis during the study (placebo, n= 2 [3.9%], tralokinumab 45mg, n =1 [2.0%], and tralokinumab 150mg, n=3 [5.9%]). Another important observation was that the serum level of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 might serve as a predictive biomarker for patients who could benefit from tralokinumab therapy.29 As with lebrikizumab, initial results with this agent for AD are encouraging and hopefully will be further supported by additional RCTs. Summary Points AD is a chronic disorder that, from the outset, requires a management strategy designed to control flares, decrease recurrences, and reduce pruritus. Cases of AD that are not adequately controlled with conventional measures and topical therapy can usually be effectively treated with incorporation of systemic therapy. It is important to assess the benefits versus the risks of various options in each case. It is also important to avoid becoming dependent on the intermittent use of intramuscular and/or oral corticosteroid therapy to control flares. Incorporation of other treatment options that can more optimally control AD over time are recommended. With the use of oral immunosuppressive agents such as cyclosporin, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and azathioprine, baseline and periodic laboratory and clinical monitoring are very important. Each of these agents carries its own significant “side effects baggage” to keep track of with relevant testing. Dupilumab is a newer option shown to be effective in markedly decreasing signs and symptoms of AD. In the opinion of the author, based on the available data and experiences thus far, dupilumab therapy offers a more favorable overall safety profile in comparison with the available oral systemic agents. Lebrikizumab and tralokinumab, both inhibitors of IL-13, are currently under development and show promise based on preliminary studies in adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD. References Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2—management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(1):116–132. Sidbury R, Tom WL, Bergman JN, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 4—prevention of disease flares and use of adjunctive therapies and approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(6):1218–1233. Del Rosso JQ, Harper J, Kircik L, et al. Consensus recommendations on adjunctive topical management of atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(10):1070–1076. Czarnowicki T, Krueger JG, Guttman-Yassky E. Novel concepts of prevention and treatment of atopic dermatitis through barrier and immune manipulations with implications for the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(6):1723–1734. Thomson J, Wernham AGH, Williams HC. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a critical appraisal. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(4):897–902. Prezzano JC, Beck LA. Long-term treatment of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(3):335–349. Admani S, Eichenfield LF. Atopic dermatitis. In: Lebwohl MG, Berth-Jones J, Heymann WR, Coulson I, Eds. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 4th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier-Saunders; 2014: 52–60. Akhavan A, Rudikoff D. Systemic agents for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. In: Rudikoff D, Cohen SR, Scheinfeld N (eds). Atopic Dermatitis and Eczematous Disorders. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group; 2014:187–199. Dhadwal G, Albrecht L, Gniadecki R, et al. Approach to the assessment and management of adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a consensus document. section IV: treatment options for the management of atopic dermatitis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22(1 Suppl):21S–29S. Mayba J, Gooderham M. Oral agents for atopic dermatitis: current and in development. In: Yamauchi PS (ed). Biologic and Systemic Agents in Dermatology. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018:319–330. Wolverton SE. Systemic corticosteroids. In: Wolverton SE (ed). Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy, 3rd edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier-Saunders; 2013:143–168. Thomas K, Bath-Hextall F, Ravenscroft J, et al. Atopic eczema. In: Williams H. Bigby M, Diepgen T, et al (eds). Evidence-Based Dermatology, 2nd edition. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2008: 128–163. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi-Genzyme. Dupixent (dupilumab) Injection, Full Prescribing Information. October 2018. Kusari A, Han AM, Schairer D, et al. Atopic dermatitis: new developments. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37(1):11–20. Patel N, Strowd LC. The future of atopic dermatitis treatment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1027:185–210. Edwards T, Patel NU, Blake A, et al. Insights into future therapeutics for atopic dermatitis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19(3):265–278. Napolitano M, Marasca C, Fabbrocini G, et al. Adult atopic dermatitis: new and emerging therapies. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2018;11(9):867–878. Silverberg JI, Kantor R. The role of interleukins 4 and/or 13 in the pathophysiology and treatment of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clinic. 2017;35(3):327–334. Snast I, Reiter O, Hodak E, et al. Are biologics efficacious in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19(2):145–165. Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Two Phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2335–2348. Gooderham MJ, Hong HC, Eshtiaghi P, et al. Dupilumab: a review of its use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3S1):S28–S36. Hajar T, Hill E, Simpson E. Biologics for treatment of atopic dermatitis. In: Yamauchi PS (ed). Biologic and Systemic Agents in Dermatology. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018: 309–317. Treister AD, Kraff-Cooper C, Lio PA. Risk factors for dupilumab-associated conjunctivitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(10):1208–1211. Thyssen JP, Toft PB, Halling-Overgaard AS, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and risk of selected ocular disease in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(2):280–286. de Bruin-Weller M, Thaci D, Smith CH, et al. Dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroid treatment in adults with atopic dermatitis with an inadequate response or intolerance to ciclosporin A or when this treatment is medically inadvisable: a placebo-controlled, randomized phase III clinical trial (LIBERTY AD CAFE). Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(5): 1083–1101. Ou Z, Chen C, Chen A, et al. Adverse events of Dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;54:303–310. Simpson E, Flohr C, Eichenfield LE, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab (an anti-IL-13 monoclonal antibody) in adults with severe moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical corticosteroids: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase II trial (TREBLE). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(5):863–871. May RD, Monk PD, Cohen ES, et al. Preclinical development of CAT-354, an IL-13 neutralizing antibody, for the treatment of severe uncontrolled asthma. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166(1):177–193. Wollenberg A, Howell MD, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. A Phase 2b dose-ranging efficacy and safety study of tralokinumab in adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). Poster presentation. Orlando, FL: American Academy of Dermatology Meeting. 3–7 Mar 2017. Tags: Atopic Dermatitis, calcineurin inhibitors, immunosuppressants, interleukin-13, interleukin-4, phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors Category: Atopic Dermatitis, Past Articles, What's New in the Medicine Chest

Via Krishan Maggon

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

December 18, 2018 1:07 PM

|

Abstract The potential of precision medicine in allergy and asthma has only started to be explored. A significant clarification in the pathophysiology of rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis, asthma, food allergy and drug hypersensitivity was made in the last decade. This improved understanding led to a better classification of the distinct phenotypes and to the discovery of new drugs such as biologicals, targeting phenotype‐specific mechanisms. Nevertheless, many conditions remain poorly understood such as non‐eosinophilic airway diseases or non‐IgE–mediated food allergy. Moreover, there is a need to predict the response to specific therapies and the outcome of drug and food provocations. The identification of patients at risk of progression towards severity is also an unmet need in order to establish adequate preventive or therapeutic measures. The implementation of precision medicine in the clinical practice requires the identification of phenotype‐specific markers measurable in biological matrices. To become useful, these biomarkers need to be quantifiable by reliable systems, and in samples obtained in an easy, rapid and cost‐efficient way. In the last years, significant research resources have been put in the identification of valid biomarkers for asthma and allergic diseases. This review summarizes these recent advances with focus on the biomarkers with higher clinical applicability. Highlights The implementation of precision medicine in allergic diseases requires a further clarification of disease phenotypes and endotypes allowing the identification of valid biomarkers. Many of the biomarkers of allergic diseases identified to date still require validation in larger cohorts and distinct geographical areas. Multidimensional approaches have a greater potential to identify valid biomarkers for allergic and chronic respiratory diseases. 1 INTRODUCTION Precision medicine for allergic diseases requires a deep understanding of immunopathology and phenotype heterogeneity in relation to clinically significant outcomes.1 Precision medicine could also help to limit the socio‐economic burden imposed by allergic and chronic respiratory diseases.2 According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), precision medicine is an emerging approach for disease treatment and prevention that takes into account individual variability in genes, environment and lifestyle for each person. In this regard, asthma and allergic conditions are ideally suited, as they represent umbrella entities comprising different diseases partially sharing immune mechanisms (endotypes) and presenting similar visible properties (phenotypes), but requiring individualized approaches for a better risk prediction and the identification of treatment responders.3 The implementation of precision medicine demands measurable indicators of biological conditions usually termed biomarkers. A valid biomarker should be quantifiable in an analytical system with well‐defined performance and need to be supported by a body of evidence which sufficiently clarifies the pathological and clinical significance of the test results.4 Moreover, the identification of novel biomarkers applicable in daily practice requires clear clinical models with well‐established extreme phenotypes, allowing a better understanding of the disease progression along its severity. Another aspect influencing the clinical applicability is the biological matrix (“sample type”) where biomarkers are measured (Table 1). Appropriate matrices should be easy to obtain, store and manipulate in standardized and reproducible measuring protocols at a reasonable cost. Moreover, in most cases a single biomarker will not adequately represent the complexity of mechanisms underlying multifactorial diseases. In this regard, the generation of multidimensional biomarker panels displays a greater potential to identify valid markers.5 The ideal biomarker Supported by a body of evidence clarifying its biological significance Quantifiable in a cost‐efficient analytical system with well‐defined performance Detectable in a biological matrix obtained in an easy, rapid and cost‐efficient way The research efforts in asthma and allergic diseases during the last decades have focused on the identification of biomarkers applicable in clinical practice. Although several markers of allergic inflammation (e.g, IgE, eosinophilia, fractional exhaled nitric oxide [FENO]) have been described, their utility in diagnosis, prognosis and therapy is still controversial.6-8 Different types of molecules (genes, metabolites, etc.) have been also proposed as biomarkers for allergic and chronic respiratory conditions. Some of them display good analytical properties, but overall, they are insufficiently robust to be extrapolated to clinical practice. This fact partially arises from a paucity of clinical models for allergic diseases, which clearly constitutes a limiting factor in the search for biomarkers. This review will summarize the biomarkers identified to date for allergic and chronic respiratory conditions, with special focus on those with higher clinical applicability. 2 NEW METHODS TO IDENTIFY BIOMARKERS: THE OMICS The different omics characterize and quantify biological molecules, which share a common feature and which provide information about the structure and function of organisms. Omics are significantly contributing to the definition of disease endotypes and phenotypes and to the identification of therapeutic targets. Recent technological advances have pushed the omics field forward by allowing higher throughputs, improving detection limits and providing software tools to analyse and visualize the data. Genomics, transcriptomics and epigenetics have been used to identify genes, RNA sub‐types and DNA modifications, respectively. Nevertheless, the validation of these observations requires the investigation of their functional consequences (e.g, the effect in transcription or splicing variants or in the functionality of proteins). Only this step permits valid conclusions for the underlying mechanisms of disease phenotypes (Figure 1). Metabolomics investigates the nature and concentration of the metabolites generated in living systems and is among the most recent approaches applied to allergy research. Metabolomics displays a high degree of versatility, as it is applicable to a great variety of matrices, whose nature can be tailored to the disease of interest.4, 7 In chronic respiratory diseases, the metabolic analysis of exhaled breath condensate seems a promising matrix for biomarker identification. Other approaches which could help phenotype chronic airway conditions include electronic nose (eNose) or nuclear magnetic resonance–based metabolomics.7 Nevertheless, the lack of standardized procedures for breath sampling, the effect of pH on some metabolites and the low concentrations are well‐established limiting factors. Individual omics display both strengths and weaknesses which overall define the validity and robustness of the results. The development of multi‐omics and multi‐matrix platforms in integrated approaches will probably provide a more holistic picture of biological situations, including allergic and chronic respiratory diseases. Nevertheless, the implementation of these advances in clinical practice requires the identification of biomarkers measurable in biological fluids obtained in an easy, rapid and cost‐efficient way. 3 UPPER AND LOWER AIRWAY DISEASES 3.1 Rhinitis Chronic rhinitis is generally divided into allergic rhinitis (AR) and non‐allergic rhinitis (NAR).9 The NAR category comprises a heterogeneous group of diseases mediated by immune or neurogenic mechanisms.10 Conversely, AR is a relatively homogeneous entity arising from IgE‐mediated inflammation.11 Local allergic rhinitis (LAR) is a disease phenotype not fitting into the AR‐NAR dichotomy.12 The skin prick test (SPT) and/or serum allergen–specific (s)IgE and the nasal allergen challenge (NAC) positively identify AR patients. Subjects with LAR are defined by a positive NAC with negative SPT and serum sIgE, whereas NAR patients test negative for the three biomarkers. Several inflammatory cells and mediators may also serve as diagnostic biomarkers for AR. Eosinophils, IL‐5, IL‐6, IL‐13 and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)‐1β increase in the nasal lavage of AR patients following NAC,13 while elevated nasal endothelin (ET)‐1 and CCL17 at baseline discriminate AR from NAR individuals.14 Compared to healthy controls, subjects with house dust mite (HDM)–induced AR have increased circulating group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2), which also correlate with serum IL‐13 and symptom scores.15 Allergen immunotherapy (AIT) is an effective treatment for AR16 and LAR17, 18 but involves considerable time and cost. Biomarkers assisting the selection of patients most likely to respond to AIT have recently been summarized.16 A proportion of sIgE to total IgE >16.2% predicted AIT success with 97.2% sensitivity and 88.1% specificity.19 In children, low serum osteopontin identifies responders to sublingual immunotherapy.20 Serum osteopontin and basophil reactivity increase after NAC21 and diminish following successful AIT.16 Moreover, subcutaneous immunotherapy with HDM armed peripheral T regulatory cells with the ability to inhibit Th2 and Th9 proliferation.22 3.2 Chronic rhinosinusitis Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is defined by nasal and sinus mucosal inflammation. Phenotyping of CRS is typically based on the presence (CRSwNP) or absence (CRSsNP) of nasal polyps on endoscopy or CT scan, whereas examination of nasal samples facilitates the endotyping (Figure 2). In Caucasian populations, nasal polyps generally show an eosinophilic infiltrate, whereas fewer than 50% of Asian patients display eosinophilic polyps.23, 24 One study identified ten CRS clusters, of which six exhibited a type 2 inflammatory profile with raised IL‐5 and eosinophilia. Type 2 clusters displayed a higher risk of nasal polyps and asthma.25 The CRSwNP phenotype has been also associated with increased ILC2 at both the tissue level and peripheral blood.26, 27 Several matrices have been used to predict CRS prognosis. Blood and tissue eosinophilia correlates with severity as measured by endoscopy and CT scan28 and can predict recurrence following endoscopic sinus surgery.23 In addition, a small study observed that programmed cell death‐1 (PD‐1) mRNA expression in nasal polyp tissue correlated with disease severity on CT scan,29 while tissue gene expression of the eosinophil marker—Charcot‐Leyden crystal protein—was associated with higher olfactory impairment.30 The level of IL‐5 and P‐glycoprotein in nasal secretions helped to predict the olfactory and the CT scan scores, respectively.31 Nasal nitric oxide (nNO) inversely correlated with CT scan‐graded severity and increased after sinus surgery.32 3.3 Asthma Asthma phenotypes are classified into those displaying dominant type 2 inflammation, and those without significant type 2 inflammation,33 with each group comprising a number of different diseases (Figure 3). Several biomarkers measurable in different matrices have been described for these asthma phenotypes. The relevance of asthma endotyping is perfectly illustrated by the case of the anti‐IL‐5 monoclonal antibody (mAb) mepolizumab whose initial lacklustre performance in unclassified asthma34 was followed by excellent outcomes when administered to patients with eosinophilic asthma.35 In any individual, the disease expression may be driven by complex endotypes with numerous mechanistic pathways3; therefore, multidimensional biomarker assessment may be required. Unsupervised statistical analyses examining various blood inflammatory mediators identified unique clusters with different clinical and pathological features. Cluster analysis using sputum mediators at exacerbation also identified distinct biologic clusters with differences in host microbiome. The subsequent paragraphs describe individual biomarkers according to their biological matrices in more detail. 3.4 Diagnostic biomarkers 3.4.1 Blood cells Peripheral blood eosinophilia and neutrophilia in asthma have been associated with different clinical characteristics, with neutrophilia indicating increased sputum production.36 In asthma, neutrophilia is also more prevalent among patients with a smoking history and persistent airflow limitation compared to non‐smoking asthma patients (4.5 × 109 vs 3.6 × 109 cells/L),37 suggesting that neutrophilia may differentiate between patients with asthma alone from those with features of asthma‐chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) overlap (ACO) syndrome. Several genes regulating immune cells such as B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes and granulocytes were up‐ or down‐regulated in severe asthma compared to healthy controls.38 In a paediatric asthma cohort, the expression of five selected genes on CD4 lymphocytes (SRM, HDAC2, SLC33A1, P2RY10 and ADD3) predicted the atopic status with 100% sensitivity and 81.3% specificity,39 while in another paediatric study, a fourteen‐gene signature (MCEMP1, AQP9, PGLYRP1, S100P, RNASE2, OLFM4, CAMP, CEACAM8, LCN2, MPO, DEFA4, ELANE, BPI, DEFA1B, CTSG, HBD, ALAS2, RPS4Y2 and RPS4Y1) was unique to a neutrophilic phenotypic cluster.40 In a recent pilot study, circulating blood microRNA profile (expressed as miRNA ratios) showed promise in differentiating allergic asthma from healthy controls.41 Lipidomic profile and gene expression after low molecular weight hyaluronic acid stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells were also shown to be different in severe asthma compared to mild asthma and healthy controls.42 Peripheral differential cell counts can also serve as surrogate markers of airway inflammation. In a meta‐analysis of 14 studies, the ability of blood eosinophils to predict airway eosinophilia showed an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.78.43 Enumeration of peripheral ILC2 has a similar utility for predicting sputum eosinophilia.44 Conversely, blood neutrophilia is less indicative of sputum neutrophilia, with an AUC of only 0.6.45 The ex vivo response of blood neutrophils and eosinophils to stimulation with N‐formyl‐methionyl‐leucyl‐phenylalanine (fMLP), in combination with relevant clinical parameters, is also able to predict sputum eosinophilia.46 3.4.2 Serum mediators The chitinase‐like protein YKL‐40 distinguished asthma from COPD and healthy controls.47 Neutrophil expression of Siglec‐9 is increased in patients with COPD and may have future potential to diagnose asthma.48 Serum (soluble‐cleaved) urokinase plasminogen–activated receptor (scuPAR) was found to be higher in severe, non‐atopic asthma in a single study49 and requires confirmation in further studies. Blood mediators can also predict airway inflammation. Overall, serum periostin moderately correlated with sputum eosinophilia.50, 51 Eosinophilic cationic protein (ECP) is more predictive of sputum eosinophilia than serum IgE,39 whereas C‐reactive protein (CRP) is weakly associated with sputum neutrophilia.52 3.4.3 Sputum cells and mediators Sputum quantitative cell count is a reference standard for airway inflammation in asthma. Four inflammatory phenotypes have been described—eosinophilic, neutrophilic, mixed granulocytic and paucigranulocytic. The neutrophilic subtype has been associated with the obese female asthma non‐type 2 phenotype.52 The Unbiased Biomarkers for the Prediction of Respiratory Disease Outcomes (UBIOPRED) study is a multicentre prospective cohort study recruiting patients with severe asthma in various European countries. Sputum analysis of the UBIOPRED cohort identified 3 transcriptome‐associated clusters (gene clusters), corresponding to eosinophilic, neutrophilic and paucigranulocytic phenotypes, respectively.53 A six‐gene signature (CLC, CPA3, DNASE1L3, IL1B, ALPL and CXCR2) can differentiate asthma patients from controls and distinguish between eosinophilic from neutrophilic asthma.54 This method has a practical advantage over sputum differential cell counts, as frozen samples can be batched for processing. Neutrophil myeloperoxidase in sputum has the potential to differentiate ACO from asthma.55 Specific microRNAs can discriminate neutrophilic from eosinophilic asthma.56 Sputum eosinophil peroxidase (EPX) correlates with sputum eosinophilia,57 as does nasal and pharyngeal EPX.58 Importantly, nasal sampling may be particularly useful for patients in whom sputum induction is unsafe or not possible. 3.4.4 Cellular bronchial samples Patients in the UBIOPRED cohort could be divided into four groups based on the expression of nine gene sets in bronchial cells, each with mixed inflammatory patterns including one with concomitant Th2 and Th17 markers.53 Interestingly, a different study found that Th2 and Th17 gene expression signatures were mutually exclusive in asthmatic airway tissue.59 The authors suggested that suppression of Th2 activity by corticosteroids may accentuate Th17 activity. Different gene signatures for Th2 and Th17 activities were used in the two studies, possibly limiting direct comparisons. The interplay between Th2 and Th17 cells is also likely to be complex, and the exact relationship between the two is still uncertain.60 3.4.5 Exhaled breath The FENO displays an AUC of 0.8 for asthma diagnosis.2 Of note, very high or low cut‐offs for FENO can, respectively, rule‐in or rule‐out asthma.27 Conversely, FENO has limited utility to predict sputum eosinophilia,43 as it is confounded by corticosteroid treatment, atopy and smoking status. Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in exhaled breath can be readily measured using eNose devices. Building on previous work which discriminates between COPD and asthma, eNose has identified label‐free clinical and inflammatory clusters among asthma and COPD patients.61 VOCs and other metabolites in exhaled breath can also differentiate asthma from healthy controls in adults and children.62-65 In a paediatric study, metabolomic analysis using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) of exhaled breath condensate identified three clusters with different inflammatory profiles based on global spectral patterns of NMR.66 3.4.6 Urine Urine metabolite analysis can accurately discriminate between asthma and COPD67 and also correlates with FENO and blood eosinophilia.68 3.5 Prognostic biomarkers 3.5.1 Blood cells Raised blood eosinophils strongly predict the risk of asthma exacerbations in both adults and children.69, 70 Blood eosinophilia also predicts longitudinal lung function decline, irrespective of smoking status.71 Blood neutrophilia is linked with airway infections in asthma11 as well as poor symptom control and increased exacerbations.72 Circulating blood fibrocytes correlate with asthma severity.73 3.5.2 Serum mediators The stability of serum periostin over disease progression facilitates its use as a biomarker.74 Elevated levels are associated with fixed and more severe airflow obstruction75, 76 and greater longitudinal lung function decline.77 Total serum IgE in children is associated with atopy, airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) and bronchial wall thickening in CT scan.69 In both adults and children, YKL‐40 level correlates with severe asthma and poor lung function.78, 79 The expression of ten selected microRNAs (HS_108.1, HS_112, HS_182.1, HS_240, HS_261.1, HS_3, HS_55.1, HS_91.1, hsa‐miR‐604 and hsa‐miR‐638) was higher in children with severe asthma.80 3.5.3 Sputum cells and mediators Sputum neutrophilia and ILC2 27 are associated with asthma severity.81, 82 Changes in sputum eosinophilia reflect fluctuations in clinical asthma control.83 Human tumour necrosis factor–like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) is an inflammatory mediator whose level in sputum correlated with higher severity, poor symptom control and decreased lung function in children with non‐eosinophilic asthma.84 3.5.4 Cellular bronchial samples Bronchial neutrophilia is present in severe (compared to non‐severe) asthma, independent of oral corticosteroid (OCS) intake.85 Gene signatures analysed in endobronchial brushing and biopsy specimens predicted persistent airflow limitation in the UBIOPRED cohort.86 In bronchoalveolar lavage samples, elevated CD4+ cells expressing both IL‐4 and IL‐17 predicted greater asthma severity.69, 87 3.5.5 Exhaled breath In both children and adults, FENO correlates with greater AHR, airway obstruction and exacerbations.69, 88 Patients with FENO >45 ppb are at greater risk for suffering >2 asthma exacerbations/year.89 Electronic nose‐measured VOCs predicted the loss of asthma control upon withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).90 Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can also be detected in exhaled breath condensates of patients with asthma and has been shown to be suppressed by anti‐inflammatory agents.91 3.5.6 Functional imaging of lungs Functional imaging with hyperpolarized gas magnetic resonance of the lung can predict asthma outcomes; persistent ventilation defects were associated with poorer asthma control.92 Greater ventilation defects are also observed in patients with uncontrolled eosinophilic inflammation.93 3.6 Biomarkers for therapeutic response prediction and measurement 3.6.1 Blood cells Blood eosinophilia identifies asthma patients responding to therapies targeting type 2 inflammation. The post hoc analyses of randomized controlled trials with the anti‐IgE mAb omalizumab identified blood eosinophilia (≥300 cells/μL) as a predictor of greater response.94, 95 Nevertheless, this finding was not reproduced in a real‐life study.96 There is a direct correlation between blood eosinophilia and the response to mepolizumab,97 the anti‐IL‐5 receptor mAb benralizumab98 and the anti‐IL‐4 receptor mAb dupilumab.99 Blood eosinophilia may also predict and monitor the response to corticosteroids. Atopic children with eosinophilia ≥300 cells/μL respond better to ICS.100 A decrease in peripheral eosinophilia is observed with the up‐dosing of ICS,101 while titration of OCS to maintain blood eosinophilia <200 cells/μL improved asthma control.102 3.6.2 Serum mediators Elevated serum periostin predicts the response to omalizumab.75, 103 Interestingly, total serum IgE does not predict the response to omalizumab, despite this molecule being not only the drug target, but also the basis for its dose calculation.104 On the other hand, a reduction in serum‐free IgE after 16‐32 weeks on omalizumab is associated with a decrease in exacerbations over two years.81 3.6.3 Sputum Sputum eosinophilia ≥3% predicts response to corticosteroids105 and mepolizumab.35 Sputum eosinophilia as a guide for ICS therapy reduced exacerbations with no associated increase in the total ICS dose.106, 107 3.6.4 Exhaled breath In patients with symptoms suggestive of AHR, elevated FENO predicts response to ICS.108 A systematic review concluded that using FENO to guide ICS therapy in adults reduced the mild but not the severe exacerbations.109 Among children, FENO also showed unclear benefits on asthma outcomes.110 A FENO level >19.5 ppb also correlated with response to omalizumab.75 3.6.5 Urine Urine bromotyrosine correlates with corticosteroid responsiveness, and the predictive accuracy further improves when combined with high FENO levels.94 Despite the previous enumeration being made in a matrix‐related fashion, the complexity of most asthma phenotypes will require multidimensional approaches to identify valid biomarkers (Table 2). This aspect is exemplified by the greatest benefit from dupilumab being observed in asthma patients exhibiting both elevated peripheral eosinophilia and FENO.99 Diagnosis Prognosis Response prediction and monitoring Blood cells Distinguish asthma from COPD Blood neutrophil Distinguish asthma from healthy controls Gene expression Inflammatory phenotyping Blood eosinophils Blood neutrophils Responsiveness of blood neutrophils and eosinophils to fMLF Exacerbations Eosinophils Neutrophils Symptoms Neutrophils Lung function Eosinophils Asthma severity Fibrocytes Predict response to anti‐IL‐5 Eosinophils Predict response to ICS Eosinophils Monitor response to corticosteroids Eosinophils Blood mediators Distinguish asthma from COPD YKL‐40 Siglec‐9 Determine atopy status scuPAR Inflammatory phenotyping ECP CRP Lung function Periostin YKL‐40 Airway remodelling IgE Asthma severity IgE MicroRNA YKL‐40 Predict response to omalizumab Periostin Reduction in serum‐free IgE Sputum cells Inflammatory phenotyping Quantitative cell count Gene signature Lung function Neutrophils Asthma severity ILC2 Loss of asthma control Eosinophils Predict response to mepolizumab Eosinophils Predict response to corticosteroids Eosinophils Guide ICS titration Eosinophils Sputum mediators Distinguish asthma from COPD MPO Inflammatory phenotyping MicroRNA Sputum/nasal/pharyngeal EPX Asthma severity TWEAK Bronchial tissue Inflammatory phenotyping Gene expression Lung function Gene signatures Asthma severity Neutrophils Exhaled breath Asthma diagnosis FENO VOC Metabolites Inflammatory phenotyping eNose Exacerbations FENO Lung function FENO Loss of asthma control eNose Predict response to ICS FENO Guide ICS therapy FENO (in adults) Urine Distinguish asthma from COPD Metabolites Inflammatory phenotyping Urine metabolites Predict response to corticosteroids Urine bromotyrosine COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP, C‐reactive protein; ECP, eosinophilic cationic protein; eNose, electronic Nose; EPX, eosinophil peroxidase; FENO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide; fMLF, N‐formyl‐methionyl‐leucyl‐phenylalanine; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; IgE, immunoglobulin E; IL‐5, interleukin‐5; ILC2, group 2 innate lymphoid cell; LTE4, leukotriene 4; MPO, myeloperoxidase; NERD, aspirin‐exacerbated respiratory disease; scuPAR, serum soluble‐cleaved form of the urokinase plasminogen–activated receptor; Siglec‐9, sialic acid–binding immunoglobulin‐type lectins‐9; TWEAK, tumour necrosis factor–like weak inducer of apoptosis; VOC, volatile organic compounds. 4 FOOD ALLERGY AND ANAPHYLAXIS The food allergy (FA) phenotypes differ on their IgE dependence and prognosis (Figure 4).111 Given this heterogeneity, the search for FA biomarkers has gained significant attention.112 4.1 IgE‐mediated food allergy The identification of children at risk of developing FA might help establish preventive strategies.112 The balance between type 2 and type 1 chemokines in cord blood influenced the sensitization to food allergens at the age of 3 years in children from Taiwan.113 Atopic individuals often display skin prick test (SPT) positivity to foods they tolerate.112 Indoleamine 2,3‐dioxygenase (IDO) is a tryptophan‐catabolizing enzyme expressed by antigen‐presenting cells.114 A high IDO activity was associated with unresponsiveness to food allergens in sensitized children from Turkey.114 Molecular allergology is a useful tool to identify clinically relevant IgE sensitization.2, 112 Specific (s)IgE to the storage proteins Cor a 14 from hazelnut or Ana o 1, 2 or 3 from cashew, correlated with clinically relevant sensitization in children from Denmark115 and the Netherlands,116 respectively. These observations might facilitate the management of patients with FA by limiting the number of oral food challenges (OFC) necessary for diagnosis.64, 112 Interestingly, a score based on the value of sIgE to Ana o 3, the SPT wheal size and the gender of the patient was proposed to predict the outcome of cashew OFC in Dutch patients.117 Basophil activation test (BAT) might also correlate with the OFC outcome in food‐dependent NSAID‐induced anaphylaxis.118 Anaphylaxis is the most severe phenotype of IgE‐mediated hypersensitivity, and the increase in serum tryptase is a helpful biomarker in most cases.119 In Canadian children, milk was the food most likely to increase serum tryptase levels.119 Interestingly, the combination of the serum levels of apolipoprotein A1 and the prostaglandin D2 metabolite 9α,11β‐PGF2, displayed a good diagnostic performance for food‐induced anaphylaxis in German patients.120 Oral immunotherapy (OIT) is a promising tool for persistent forms of IgE‐mediated FA.111, 121-123 In anaphylactic children from the United States, successful milkOIT induced the increase in peripheral invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells and skewed milk‐stimulated iNKT cells from a type 2 to a type 1 profile.124 Furthermore, successful OIT reduced blood eosinophils and increased several mediators functionally related to type 1 immunity (adipokines, leptin or resistin) in milk‐allergic children from Finland.125 A higher baseline sIgA and a rapid increase in sIgG1 after OIT initiation identified good responder egg‐allergic children from Japan.126 The adverse reactions (AdR) during OIT limit its use in the clinics.123 In children undergoing peanutOIT, the presence of allergic rhinitis and the SPT wheal size were associated with systemic and gastrointestinal AdR.127 Adjuvant therapy with omalizumab might reduce AdR during OIT,123 and the combination of basophil reactivity and sIgE/total IgE ratio at baseline could identify patients more likely to benefit from omalizumab during milkOIT.128 Beyond the oral route, other administration routes are under investigation for severe FA.123 Sublingual immunotherapy with Pru p 3, the lipid transfer protein from peach, induced anti‐inflammatory PDL‐1+ dendritic cells and IL‐10+ T regulatory cells in responder patients from Spain.129, 130 4.2 Other types of food allergy The diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis requires the demonstration of >15 eosinophils/high‐power field in the oesophagus of individuals with suggestive symptoms.131 Oesophageal eosinophilia correlated with male gender and the number of positive food sIgE tests in American children.132 This observation might help to limit the number of endoscopies required for diagnosis.131 The management of food protein‐induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIE) patients involves consecutive OFCs to asses for disease resolution.133 In Japanese children with FPIES, the OFCs induced the activation of intestinal and peripheral eosinophils.134 Interestingly, the peripheral level of C‐reactive protein and of eosinophilia correlated with a poor and good prognosis, respectively, in Japanese patients with FPIES.135 Despite the progress made in recent years, most biomarkers remain to be validated in larger populations and distinct geographical areas. Moreover, growing evidence suggests that airway allergy influences many of the parameters identified as FA biomarkers.136, 137 In this regard, the clarification of atopic phenotypes and their relationship with FA will improve the interpretation of biomarkers.68, 138 5 DRUG HYPERSENSITIVITY A summary of the different drug hypersensitivity phenotypes can be seen in Figure 5. 5.1 Cross‐intolerance to NSAIDs Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most common triggers of drug hypersensitivity reactions, and in most cases, these reactions are not mediated by immunological mechanisms.139 In non‐selective or cross‐intolerant reactions, NSAIDs from different groups provoke skin or respiratory symptoms.140 In these cases, the reaction‐inducing potential does not rely on the chemical structure of the drug, but on its COX‐1 inhibitory activity.140 Aspirin‐ or NSAID‐exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD and NERD, respectively) is the most studied phenotype of cross‐intolerance. This entity is defined by the onset of respiratory symptoms upon intake of NSAIDs and is related to a dysregulation of arachidonic acid (AA) metabolism with overproduction of leukotrienes (LT) and prostaglandins (PG).141 Many NERD subjects have concomitant CRS and asthma.141 In a Korean study, NERD patients were divided into four sub‐phenotypes based on the presence of CRS, urticaria and atopy.142 Interestingly, significant differences existed in asthma severity, total serum IgE, sputum and peripheral eosinophilia, and urinary LTE4 (uLTE4).142 In American patients, uLTE4 helped to identify aspirin sensitivity in patients with different nasal inflammatory conditions.143 A recent meta‐analysis reported that the sensitivity and specificity of uLTE4 for identifying aspirin sensitivity in asthma ranged from 0.55 to 0.81 and from 0.77 to 0.82, respectively, depending on the detection method.144 Serum LTE4 in combination with LTE4/PGF2α ratio might help to detect NERD among other asthma phenotypes.145 Aspirin provocation increased 8‐iso‐PGE2 in the exhaled breath condensate of NERD patients and correlated with uLTE4.146 Platelet activation was also associated with overproduction of AA metabolites and to a reduced lung function in NERD patients.147 Other biomarkers beyond AA metabolites have been related to NERD. The serum sphingosine‐1‐phosphate was higher in NERD patients than in other asthmatics.148 American patients with NERD displayed higher activation of mast cells, basophils and platelets measured in nasal microparticles than other CRS individuals.149 Overall, these biomarkers might facilitate the diagnosis of NSAID hypersensitivity by decreasing the need for drug provocations. Some cross‐intolerance phenotypes resolve over time,150 and these biomarkers might help determine the most adequate timing to test for aspirin tolerance. 5.2 Immune‐mediated reactions These conditions can be divided into immediate and non‐immediate reactions arising from IgE‐ and T cell–mediated mechanisms, respectively (Figure 5).112 5.3 Immediate reactions Betalactams (BL) and fluoroquinolones (FQ) are the most common drugs involved in immediate reactions.139 5.3.1 Betalactams Skin testing displays a diagnostic sensitivity of up to 70%.151 Available in vitro tests include immunoassays to quantify serum BL‐sIgE, including the commercial ImmunoCAP© (Thermo‐Fisher, Uppsala, Sweden).151 Its sensitivity shows a high variability (0%‐50%),152 depending on the reaction severity and the time gap at the moment of measurement.153 Moreover, ImmunoCAP© can induce false‐positive results when testing for Penicillin‐V.154 Increased serum tryptase during the acute phase of reactions can confirm mast cell activation 112 and correlates with the severity.155 The sensitivity of BAT for BL allergy ranges from 22% to 55% with a specificity of up to 96%.156, 157 5.3.2 Fluoroquinolones Skin testing is not useful for the diagnosis of FQ allergy,158 and there are no available immunoassays. The CD63‐based BAT displayed 83.3% sensitivity and 88.9% specificity for ciprofloxacin allergy.159 Surprisingly, CD203c outperforms CD63 as BAT‐activation marker for moxifloxacin allergy, yet its sensitivity was low (36.4%).159, 160 These data question the role of basophils in moxifloxacin allergy, but identify BAT as a promising tool for ciprofloxacin allergy. 5.4 Non‐immediate reactions Patch testing and intradermal test with delayed reading are useful in vivo biomarkers. The sensitivity of the in vitro lymphocyte transformation test (LTT) is lower than that of BAT for immediate reactions.63, 155 A combination of granzyme B and granulysin expression in blood cells can detect lymphocyte activation in the setting of severe cutaneous reactions like Stevens‐Johnson syndrome.161 The screening for HLAB*57:01 before abacavir prescription is recommended by regulatory agencies,162 as it showed 100% of negative predictive value for immunologically confirmed abacavir hypersensitivity.163 The screening for HLAB*15:02 is also recommended before carbamazepine treatment in patients at high risk (Han Chinese, Vietnamese, Cambodians, etc.).164, 165 6 CONCLUSIONS The potential of precision medicine in the fields of allergy and chronic respiratory diseases has only started to be explored. A better definition of disease phenotypes and endotypes based on treatable traits and other clinically significant aspects is a prerequisite to progress in individualized therapies. In the last decade, we have seen an improvement in the definition of allergic respiratory disease, and we have gained insights into other eosinophilic phenotypes of rhinitis, CRS and asthma. This knowledge has translated into a significant broadening of therapeutic options, including (but not limited to) new biologicals. Because precision medicine needs to be performed in a cost‐efficient way, there is a need to identify responder patients to these new drugs. On the other hand, the available therapies for NAR and non‐eosinophilic CRS and asthma are much more limited, reflecting the important knowledge gaps in the pathophysiology of those phenotypes. Similarly, there is a need to progress in the definition of EoE and FPIES in order to improve the clinical management of the patients. The clarification of the disease mechanisms behind IgE‐mediated food allergy and drug hypersensitivity will help identify patients at risk of developing allergic reactions, limit the number of required provocations and establish preventive strategies. Nevertheless, the clarification of disease phenotypes per se does not guarantee the implementation of precision medicine in the clinical practice, as this step requires the detection of valid biomarkers. This search will be a long and resource‐consuming path requiring large population cohorts. Among the different disciplines applied to biomarker identification, metabolomics appears as a promising tool, yet growing evidence indicates that valid biomarkers will be detected by multidimensional strategies. Valid biomarkers do not only need to accurately reflect the phenotype‐specific disease mechanisms, but also to be quantifiable in a rapid, easy and cost‐efficient way. Only under these premises, the research in biomarker identification will be able to impact the clinical practice and translate into an improved diagnosis, management, and treatment of patients with allergic and chronic respiratory diseases. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The present work has been supported by the Institute of Health “Carlos III” of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grants cofunded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF): thematic network and cooperative research centres ARADyAL RD16/0006/0001 and RD16/0006/0015, and research projects PI15/02256, PI16/00249, PI17/01318. This article has been also supported by research grants provided by the Regional Ministry of Health of Andalusia: PI‐0346‐2016 and PC‐0278‐2017. I Eguiluz‐Gracia holds a Rio Hortega research contract (CM17/00140) of the Institute of Health “Carlos III,” Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (cofounded by the European Social Fund, ESF). CONFLICT OF INTEREST None of the authors have any conflict of interest in relation to this article. REFERENCES

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

November 8, 2018 11:10 AM

|

Omalizumab is approved for use in chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU); however, it is not approved for chronic inducible urticaria (CIndU).The aim of the present study was to assess the effectiveness...

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

October 4, 2018 8:13 AM

|

Learn more about urticaria, also known as hives, and angioedema; skin conditions which give wheals or swelling. Read our urticaria (hives) and angioedema factsheets for treatment tips.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

July 30, 2018 1:19 PM

|

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

June 24, 2018 5:15 AM

|

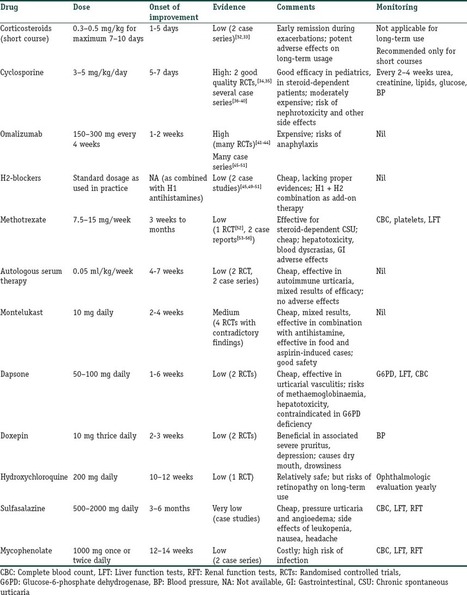

This article is developed by the Skin Allergy Research Society of India for an updated evidence-based consensus statement for the management of urticaria, with a special reference to the Indian context.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

February 3, 2018 11:31 AM

|

Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016 Apr 13;12:585-97. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S105189. eCollection 2016. Review

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

July 8, 2017 1:52 AM

|

Treatment with second-generation antihistamines is recommended in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). Some patients remain unresponsive even after up-dosing up to fourfold. Many third line treatment options have limited availability and/or give rise to significant side effects. We investigated effectiveness and safety of antihistamine treatment with dosages up to fourfold and higher. This retrospective analysis of patients’ records was performed in adult CSU patients suffering wheals and/or angioedema (AE). Demographic, clinical, and therapeutic data was extracted from their medical records. We recorded the type, maximum prescribed dosage, effectiveness, and reported side effects of antihistamine treatment. Of 200 screened patients, 178 were included. Treatment was commenced with a once daily dose of antihistamines. Persisting symptoms meant that up-dosing up to fourfold occurred in 138 (78%) of patients, yielding sufficient response in 41 (23%). Up-dosing antihistamines was necessary in 110 (80%) patient with weals alone or weals with angioedema and 28 (64%) with AE only (p = 0.039). Of the remaining 97 patients with insufficient response, 59 were treated with dosages higher than fourfold (median dosage 8, range 5–12). This was sufficient in 29 patients (49%). Side effects were reported in 36 patients (20%), whereof 30 (17%) experienced somnolence. Side effects after up-dosing higher than fourfold were reported in six out of 59 patients (10%). Up-dosing antihistamines higher than fourfold dosage seems a feasible therapeutic option with regards to effectiveness and safety. The need for third line therapies could be decreased by 49%, with a very limited increase of reported side effects.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

December 3, 2016 11:00 AM

|