Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

Allergen immunotherapy (AIT) treatment for allergic rhinitis and asthma is used by

2.6 million Americans annually. Clinical and sterility testing studies identify no

risk of contamination or infection from extracts prepared using recommended aseptic

techniques, but regulatory concerns persist.

Via Krishan Maggon

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

July 23, 2019 2:13 PM

|

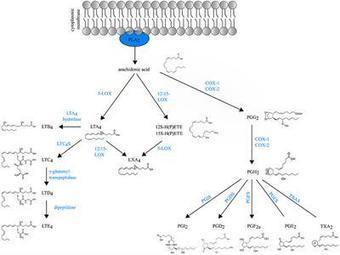

Asthma is a common lung disease affecting 300 million people worldwide. Allergic asthma is recognized as a prototypical Th2 disorder, orchestrated by an aberrant adaptive CD4+ T helper (Th2/Th17) cell immune response against airborne allergens, that leads to eosinophilic inflammation, reversible bronchoconstriction, and mucus overproduction. Other forms of asthma are controlled by an eosinophil-rich innate ILC2 response to epithelial damage, whereas in some patients with more neutrophilia, the disease is driven by Th17 cells. Dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages are crucial regulators of type 2 immunity in asthma. Numerous lipid mediators including the eicosanoids prostaglandins and leukotrienes influence key functions of these cells, leading to either pro- or anti-inflammatory effects on disease outcome. In this review, we will discuss how eicosanoids affect the functions of DCs and macrophages in the asthmatic lung and how this leads to aberrant T cell differentiation that causes disease.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

June 21, 2019 11:41 AM

|

Asthma is prevalent but largely undiagnosed and undertreated in China. It is crucial

to increase the awareness of asthma and disseminate standardised treatment in clinical

settings to reduce the disease burden.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

June 2, 2019 4:36 AM

|

Summary Assessment and management of asthma is complicated by the heterogeneous pathophysiological mechanisms that underlie its clinical presentation, which are not necessarily reflected in standardized management paradigms and which necessitate an individualized approach to treatment. This is particularly important with the emerging availability of a variety of targeted forms of therapy that may only be appropriate for use in particular patient subgroups. The identification of biomarkers can potentially aid diagnosis and inform prognosis, help guide treatment decisions and allow clinicians to predict and monitor response to treatment. Biomarkers for asthma have been identified from a variety of sources, including airway, exhaled breath and blood. Biomarkers from exhaled breath include fractional exhaled nitric oxide, measurement of which can help identify patients most likely to benefit from inhaled corticosteroids and targeted anti‐immunoglobulin E therapy. Biomarkers measured in blood are relatively non‐invasive and technically more straightforward than those measured from exhaled breath or directly from the airway. The most well established of these are the blood eosinophil count and serum periostin, both of which have demonstrated utility in identifying patients most likely to benefit from targeted anti‐interleukin and anti‐immunoglobulin E therapies, and in monitoring subsequent treatment response. For example, serum periostin appears to be a biomarker for responsiveness to inhaled corticosteroid therapy and may help identify patients as suitable candidates for anti‐IL‐13 treatment. The use of biomarkers can therefore potentially help avoid unnecessary morbidity from high‐dose corticosteroid therapy and allow the most appropriate and cost‐effective use of targeted therapies. Ongoing clinical trials are helping to further elucidate the role of established biomarkers in routine clinical practice, and a range of other circulating novel potential biomarkers are currently being investigated in the research setting. Introduction Asthma is a heterogeneous disease that is usually characterized by chronic airway inflammation and structural change with associated airway dysfunction 1. It is defined by a history of respiratory symptoms (such as wheeze, shortness of breath, chest tightness and cough), which vary over time and in intensity, together with variable expiratory airflow limitation 1. Asthma affects approximately 300 million individuals worldwide, with prevalence rates ranging from 1% to 16% in different countries 2. In the UK, 5.4 million people currently receive treatment for asthma (1.1 million children [1 in 11] and 4.3 million adults [1 in 12]) and, on average, three people per day die from asthma 3. It is now clear that asthma comprises various disease subtypes with similar clinical manifestations, but with differing underlying pathophysiological mechanisms 1. The classification of asthma has consequently evolved as understanding regarding its pathophysiology has increased. Having initially been categorized in terms of ‘allergic’ or ‘non‐allergic’ asthma, a distinction was then made between ‘eosinophilic’ (‘type 2 high’) and ‘non‐eosinophilic’ (‘type 2 low’) asthma. Advances in disease understanding subsequently indicated that there may be subgroups of type 2 high asthma that differ in terms of both the presence of underlying allergy and the potential source of type 2 cytokines. This led to the current concept of ‘type 2 (T2) asthma’, which is characterized by high levels of type 2 interleukins (ILs), such as IL‐4, IL‐5 and IL‐13, and involves type 2 helper T cells (Th2 cells), mast cells, basophils, B cells and type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) 4-6. It is currently believed that Th2 cells and ILC2s are primarily responsible for the production of the majority of type 2 cytokines in the airway, including IL‐4, IL‐5, IL‐9 and IL‐13 5, 7. The prolonged presence of activated inflammatory cells leads to chronic inflammation and airway remodelling 8. Since the 1990s, efforts to characterize asthma in terms of clinical, physiological and pathological parameters have led to the concept of asthma ‘phenotypes’ and ‘endotypes’ 9-13. The term ‘phenotype’ is used to denote a recognizable cluster of similar clinically observable characteristics, which can be identified using statistical methods (e.g. cluster analysis) without establishing an underlying aetiology or pathophysiology 12, 14, 15. By contrast, the term ‘endotype’ is used to describe a disease subtype with a clearly elucidated pathophysiology 15. Current approaches to asthma stratification primarily rely on identifying phenotypes, as the level of understanding required to establish endotypes has, in general, not yet been achieved 15. Asthma can be stratified in many ways: in terms of clinical history, physiology, inflammatory phenotype profile or biomarkers, and also in terms of therapeutic response to individual treatments. Stratification is central to the effective management of asthma, as it facilitates the personalization of treatment tailored to the individual's specific needs. This is particularly important with the emergence of targeted forms of asthma therapy, such as those targeting specific pro‐inflammatory cytokines 16. Asthma management in the UK is currently based on empirical stepwise treatment, with inhaled corticosteroids being standard of care for mild asthma, and combinations of inhaled corticosteroids and long‐acting beta agonist therapy plus further add‐on therapies, as required, for more severe asthma 17. International guidelines define severe asthma as ‘asthma that requires treatment with high‐dose inhaled corticosteroids plus a second controller and/or systemic corticosteroids to prevent it from becoming “uncontrolled,” or that remains ‘uncontrolled’ despite this therapy’ 18. Approximately 3–5% of asthma sufferers are unresponsive to available treatments and severe, therapy‐resistant asthma has become increasingly recognized as a major unmet need 18, 19. Moreover, severe refractory asthma is associated with a substantial burden in terms of healthcare costs. In the UK, the direct treatment costs from a National Health Service perspective, based on data from the British Thoracic Difficult Asthma Registry, were estimated to be £2912–4217 per patient per year 20. Identification of therapy resistance in difficult‐to‐treat asthma is hampered by poor adherence to treatment, which is known to be a problem in many asthma patients 21, 22. However, there is also a subset of patients who have poorly controlled asthma with persistent type 2 inflammation, despite adherence with high‐dose inhaled steroids. These patients often progress to systemic steroid treatment, which is associated with significant morbidity 23, and some of the new therapies targeting type 2 inflammation are likely to be of value for treating such patients in the future. It is therefore important to identify patient subgroups likely to benefit from targeted forms of treatment 19, 24. As the diagnosis of asthma is usually based on reported symptomatology and lung function tests 25, which are unable to assess airway inflammation and stratify the disease into discriminated phenotypes, there is a need for biomarkers to help with the accurate identification of clinically relevant phenotypes, not only to potentially aid diagnosis and inform prognosis, but also to guide treatment decisions, and predict and monitor treatment response. A biomarker is defined as ‘a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes or pharmacological responses to a therapeutic intervention’ 26. The ideal characteristics of a biomarker are outlined in Table 1 15, 27-29. Essentially, the ideal biomarker should be easily measurable, have the ability to identify a mechanism known to be important in the pathogenesis of the disease, be reliable and reproducible in the clinical setting and be cost‐effective. It should ideally be mechanistically linked to the therapeutic target and responsive to intervention 15, 27-29. Biomarkers for asthma have been identified from a variety of sources, including the airway, exhaled breath and blood. The primary focus of this article is the role of T2 biomarkers in asthma management. Characteristic Details Easily measurable Non‐invasive Not requiring complex or potentially dangerous interventions Easy to collect in the ‘real‐world’ setting Ability to distinguish a mechanism causally linked to important clinical outcome High sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values Correlation with treatment responses (e.g. to allow treatment adjustment) ’Normalization’ with successful treatment Reliable and reproducible in the clinical setting Little or no day‐to‐day variation (unless the variation is meaningful) Ability to provide information about disease prognosis and clinical outcomes Able to help inform disease management Mechanistically linked to the therapeutic target Able to provide better understanding of underlying pathophysiology Cost‐effective Airway biomarkers Bronchial biopsy has been considered the ‘gold standard’ for investigating airway inflammation and tissue remodelling, but it is invasive, costly, complex to perform and not readily accessible in clinics or research centres 28. Bronchoalveolar lavage also involves bronchoscopy, is often poorly tolerated by patients with asthma and also has to be conducted in a specialized hospital, preventing its widespread use in routine clinical practice 15. Sputum induction is less invasive and more cost‐effective than bronchoalveolar lavage, but it is still invasive and too technically complex and difficult to standardize for routine practice, and therefore generally only used in specialized centres and usually in a research setting 15, 25. Induced sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage contain cells (such as eosinophils and neutrophils) and supernatant containing cytokines, which can be used to predict asthma severity and exacerbations 25, 28. Indeed, the discernment of distinct inflammatory phenotypes through analysis of the cellular component of induced sputum is an early example of how biomarkers can be used to achieve asthma stratification 30, although the utility of these particular biomarkers in the personalization of treatment is unclear 15. Biomarkers in exhaled breath Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) The measurement of FeNO is a relatively simple, fast, non‐invasive and reproducible technique that has been used as a surrogate measure of airway inflammation in asthma 15, 29. The American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society have standardized a method to measure FeNO 31, providing a simple, fast, non‐invasive and reproducible technique in asthma management 15. Findings from the Isle of Wight birth cohort study indicated that FeNO may be a useful biomarker for atopic asthma (where atopy was defined as having ≥ 1 positive skin prick test to either a food or aeroallergen) 32. High FeNO levels (> 47 ppb) have been shown to be associated with airway eosinophilia and corticosteroid responsiveness 33 and also to be prognostic for asthma exacerbations 34. Similarly, high (≥ 19.5 ppb) vs. low (< 19.5 ppb) FeNO levels have been associated with greater treatment effects with omalizumab, a targeted anti‐immunoglobulin E (IgE) therapy 35. Indeed, of the three potential biomarkers investigated in this study (FeNO, blood eosinophil count, serum periostin level), a high level of FeNO was the strongest predictor of response to omalizumab therapy 35. The degree of suppression of FeNO resulting from inhaled corticosteroid therapy has been used to identify non‐adherence to this treatment in a difficult‐to‐treat asthma population 36, and it has been suggested that this test could be used to help identify patients who are truly refractory to corticosteroid treatment, before considering dose escalation or the introduction of more costly targeted forms of therapy 22. In addition, a treatment algorithm in which FeNO concentrations were used to adjust patients’ inhaled corticosteroid dose during pregnancy was shown to significantly reduce the frequency of asthma exacerbations 37. However, the clinical utility of FeNO measurement in asthma is not clear‐cut, as studies investigating the association between asthma control and FeNO have yielded inconsistent results 25, perhaps partly because FeNO levels can be influenced by factors other than asthma, including age, medication use, smoking status and dietary factors 38. Controversy over the clinical utility of FeNO as biomarker for asthma is reflected in current treatment guidelines. In the UK, the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence Diagnostics Draft Guidance 12 (due for formal publication in 2017) advocates the use of FeNO testing to help diagnose asthma in adults and children 39; however, the Global Initiative for Asthma has concluded that FeNO cannot be recommended for asthma diagnosis and therapy monitoring 1. Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) VOCs can be measured in exhaled breath and their profile patterns might potentially be used to diagnose and distinguish between asthma and other conditions (e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and discriminate between different asthma phenotypes 15, 40. ‘Electronic nose’ technology provides a means of studying VOCs in individual patients, by utilizing an array of sensors that react with different VOCs to generate a specific ‘breath print’ 41. This approach has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for discriminating between asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and healthy patients 42, and has been used in a clinical setting to discriminate between different inflammatory asthma phenotypes (eosinophilic, neutrophilic, paucigranulocytic) in patients with persistent asthma 40. It has also shown greater accuracy than measurement of FeNO or eosinophils for predicting responsiveness to corticosteroids 43. However, it does not appear to be able to distinguish mild asthma from severe asthma 44. The clinical utility of VOC measurement needs to be validated in a large asthma cohort; longitudinal data and guidelines for VOC measurement are also lacking 25. Exhaled breath condensate Exhaled breath condensate collection is an easy, non‐invasive, reproducible technique that can be used to measure several asthma biomarkers, including pH, markers of oxidative stress (including hydrogen peroxide), microRNA profiles, lipoxins, cytokines and leukotrienes 25, 28, 45. However, the technique is still in the research phase; a standardized methodology for exhaled breath condensate collection is required and reference values need to be established. Exhaled breath temperature Exhaled breath temperature is another potential biomarker for asthma, as blood flow in asthmatic airways is increased, resulting in a measurable increase in exhaled breath temperature 46, 47. Exhaled breath temperature is unlikely to be able to distinguish between asthma phenotypes, but it could potentially be used to monitor efficacy of asthma treatment, although this requires further research 15. Biomarkers in blood Biomarkers measured in blood are relatively non‐invasive, and less technically demanding than the assessment of biomarkers from exhaled breath. Several blood biomarkers are clinically well established and already used to help characterize asthma subtypes and monitor response to treatment. Certain novel blood biomarkers have also been identified, which may impact asthma management in the future. Eosinophil counts Peripheral blood eosinophil counts have been extensively studied as a potential biomarker for asthma. Eosinophils are important drivers of severe exacerbations in asthma 13, and blood eosinophil counts reflect inflammation in the asthmatic airway, being useful in the early detection of exacerbations and the regulation of steroid dosage 48. Mepolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against IL‐5, is a selective and effective inhibitor of eosinophilic inflammation 49. Mepolizumab treatment has been shown to significantly decrease the frequency of exacerbations in patients with refractory asthma and evidence of eosinophilic airway inflammation, despite treatment with high doses of corticosteroids 13. These findings have been further supported by more recent trials of mepolizumab treatment in patients with eosinophilic asthma 50, 51. The benefits of treatment are closely associated with the blood eosinophil count, and the clinical response is marked in patients with pre‐treatment eosinophilia and absent in patients with a count < 150/μL 50. Similarly, Phase II trials of the anti‐IL‐5 agent, benralizumab, have demonstrated its effectiveness in reducing asthma exacerbation and improving lung function and asthma control in patients with uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma and acute asthma 52-54, and Phase III trials of the anti‐IL‐5 agent, reslizumab, have demonstrated its effectiveness in improving asthma control and symptoms, lung function and quality of life in patients with inadequately controlled asthma and elevated blood eosinophil counts 55-57. Blood eosinophil levels have also been shown to predict treatment benefit from biological therapies targeting IgE, IL‐4 and IL‐13 in patients with asthma 35, 58, 59. For example, in the EXTRA study, in which patients with uncontrolled severe persistent allergic asthma received 48 weeks of omalizumab treatment, patients with pre‐defined high baseline levels of peripheral blood eosinophil counts (≥ 260/μL) experienced a significant reduction in protocol‐defined exacerbations (–32%; P = 0.005), whereas those with pre‐defined low baseline levels (< 260/μL) did not (–9%; P = 0.54) 35. In a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study of lebrikizumab (a monoclonal antibody to IL‐13), conducted in adults with asthma who were inadequately controlled despite inhaled glucocorticoid therapy, there was a trend towards a lower rate of protocol‐defined exacerbations in patients treated with lebrikizumab, compared with those treated with placebo, after 24 weeks (P = 0.16) 58. However, in the pre‐specified ‘Th2 high’ subgroup, defined on the basis of baseline peripheral blood eosinophil count and serum IgE level, the rate of exacerbations was 60% lower in the lebrikizumab group than in the placebo group (P = 0.03) 58. Although peripheral blood eosinophil data are readily available from a standard complete blood count, the clinical utility of the blood eosinophil count as a biomarker for asthma may be limited in some situations by its low specificity for eosinophilic airway inflammation, as a raised count can also be caused by other allergies, autoimmune disease and parasitic infections 25. In addition, the sensitivity of blood eosinophil levels as a biomarker for asthma is likely to decrease with the use of anti‐IL‐5 treatment, due to the differential effect of such treatment on eosinophilic inflammation in different tissue compartments. Consequently, a suppressed peripheral blood eosinophil count in patients receiving anti‐IL‐5 therapy does not reliably inform the level of underlying eosinophilic airway inflammation required to determine therapy response when symptoms and/or exacerbations remain persistent. Activation profile of eosinophils Changes in the activation profile of eosinophils in peripheral blood reflect their response to pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory signals; for example, membrane‐bound integrins become activated when eosinophils are primed to leave the circulation and enter tissue 60. Such changes have been used to diagnose the type and severity of allergic asthma 25. In a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study of inhaled corticosteroid withdrawal in patients with mild asthma, activation of β1 integrins (identified using a monoclonal antibody) predicted decreased forced expiratory volume in 1 s more effectively than either FeNO or the percentage of eosinophils in sputum, and correlated with FeNO following inhaled corticosteroid withdrawal 61, 62. However, such differences in the activation profile of eosinophils are likely to be too subtle for routine application 25. Periostin Genomewide gene expression studies in bronchial epithelial cells identified two subsets of patients, ‘Th2 high’ and ‘Th2 low’ patients 63. This terminology was based on the observation that the highest expressed genes in the ‘Th2 high’ population were all inducible by IL‐13. Moreover, an analysis of gene expression in bronchial biopsies from the same patients demonstrated differences in IL‐13 gene expression levels between patients with ‘Th2‐high’ and ‘Th2‐low’ asthma or healthy controls 63. However, even with highly sensitive assays, differences in serum IL‐13 levels cannot reliably be detected 64. There is therefore a need for a surrogate systemic biomarker of Th2‐driven asthma (recently recognized as T2 asthma) that is mechanistically linked to IL‐13. Periostin, the gene for which was one of those most highly expressed in the Th2 high population in the study by Woodruff et al. 63, is induced by IL‐4 and IL‐13 in airway epithelial cells and lung fibroblasts 65. Periostin is a matricellular protein that has been identified as a component of subepithelial fibrosis in bronchial asthma 65, 66 and which has a potential role in eosinophilic airway inflammation 67 and regulation of mucus production 68. These mechanisms suggest that periostin is a potential mediator of asthma 69. Importantly, periostin has been shown to be a systemic biomarker of T2, IL‐13‐driven, corticosteroid‐responsive asthma 63, 66. In the BOBCAT study, conducted in patients with asthma who remained symptomatic despite maximal inhaled corticosteroid treatment, serum periostin was found to predict eosinophilic airway inflammation (defined as ≥ 22 tissue eosinophils/mm2 on bronchial biopsy or sputum eosinophilia ≥ 3%) better than FeNO levels, blood eosinophil counts or serum IgE levels (Fig. 1) 70. However, in another study, serum periostin was unable to distinguish eosinophilic asthma (defined as sputum eosinophils ≥ 3%) from non‐eosinophilic airway inflammation, whereas blood eosinophil count and FeNO level were able to do so 71. Serum periostin levels in patients with asthma have been shown to be significantly higher than those in healthy subjects, and to correlate positively with blood eosinophil counts, serum IgE and eosinophil cationic protein levels (P < 0.05) 72. High serum periostin levels have also been shown to predict asthmatic activity after reduction in inhaled corticosteroids in patients with apparently stable, well‐controlled asthma 73. Similarly, serum periostin appears to be a useful biomarker for the development of airflow limitation in patients with asthma on prolonged treatment with inhaled corticosteroids 74. These findings indicate that serum periostin may be a biomarker for responsiveness to inhaled corticosteroid therapy, which may therefore be useful in helping to identify patients as suitable candidates for alternative targeted forms of therapy 75. Serum periostin has also been investigated as a biomarker for predicting treatment response to targeted asthma therapies. For example, patients with asthma with high baseline levels of serum periostin reportedly benefit most from anti‐IL‐13 therapy with lebrikizumab and tralokinumab 58, 76, 77. Recently, topline results from 2 Phase III, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab in patients with severe asthma were released (LAVOLTA I and II) 78. LAVOLTA I met its primary endpoint by demonstrating a significant reduction in the rate of asthma exacerbations in patients with high levels of serum periostin or blood eosinophils. However, the exacerbation reduction results observed in LAVOLTA II did not attain statistical significance 78. The potential prognostic role of periostin as a biomarker to predict exacerbations and to help guide asthma therapy is being further investigated in ongoing clinical trials, such as the UK Refractory Asthma Stratification Programme (RASP‐UK; see ‘Implications of biomarkers of type 2 inflammation for current clinical practice’ section) 24. Current evidence suggests that periostin can help identify patients with T2 asthma, but additional biomarkers are likely to be required in order to further subdifferentiate this phenotype 15. The use of periostin as a biomarker in asthma management is currently limited by the need for well‐established and validated cut‐off values for high and low serum periostin levels, and thus the need for standardized measurement techniques. In addition, the specificity of periostin for asthma may be confounded by the presence of several factors, including comorbidities in which it is also known to be involved, such as metastatic cancer, renal injury, bone fracture and osteoporosis 79-81. Chitinase‐like protein YKL‐40 Serum levels of the chitinase‐like protein, YKL‐40, have been shown to be significantly elevated in patients with asthma vs. controls 82-84. However, reports regarding correlations between serum YKL‐40 levels and asthma severity or other asthma biomarker levels (eosinophils, total serum IgE, FeNO) have been inconsistent 70, 82-85. YKL‐40 polymorphisms have been shown to be associated with asthma, bronchial hyperresponsiveness and reduced lung function 86. It remains to be determined whether YKL‐40 is involved in the pathophysiology of asthma or is simply a marker of extracellular tissue remodelling 87, and its clinical utility in asthma management remains to be established. ILC2S Emerging evidence has indicated that activated ILC2s are capable of producing large amounts of inflammatory cytokines and may play a crucial role in T2 asthma 88. In a recent study conducted in 150 patients with mild‐to‐moderate asthma and 42 healthy controls, the percentage of ILC2s in peripheral blood was shown to correlate significantly with sputum eosinophil counts (P < 0.001), and to have a sensitivity of 67.7% and a specificity of 95.3% when used to distinguish eosinophilic from non‐eosinophilic patients with asthma 89. The percentage of ILC2s in peripheral blood therefore appears to be a surrogate marker of airway eosinophilic inflammation 89, although the clinical utility of this as a potential biomarker in asthma management is likely to be limited by difficulties in measuring ILC2 counts. IgE Serum levels of total and allergen‐specific IgE have been considered as potential biomarkers for study population characterization and for the assessment of effectiveness in intervention studies in asthma 90. However, in clinical trials of the anti‐IgE therapy, omalizumab, pre‐treatment levels of total IgE or antigen‐specific IgE were inconsistent in predicting response to treatment 91, 92. The clinical utility of measuring IgE serum levels may be limited by low specificity 25. Other circulating biomarkers Many other circulating molecules and proteins have been investigated as potential biomarkers for asthma (Table 2). Whilst some of these are related to clinically important features cross‐sectionally, we do not currently have evidence that they are prognostic or capable of predicting treatment responses. Potential biomarker Details ECP Component of eosinophil secondary granules, released during degranulation Increased serum ECP levels are indicative of systemic eosinophilic inflammation 93 Serum ECP levels are often increased in patients with asthma 94 and correlate well with airway inflammation 95 May have an advantage as a marker of activated eosinophils, although there is little evidence that ECP is more informative than blood eosinophil counts Serum ECP levels are affected by other factors, in particular smoking 95 Eotaxin (CCL11) Potent and selective chemoattractant for human eosinophils 93 Serum eotaxin levels correlate with ECP levels in asthma patients 96 Has been used to predict symptom severity during tapering of inhaled corticosteroid treatment 97 DPP‐4 Glycoprotein induced from bronchial epithelial cells by IL‐13 stimulation; highly expressed in bronchial epithelial cells of untreated asthma patients 98 In a Phase IIb study of tralokinumab therapy in severe uncontrolled asthma, patients with baseline serum DPP‐4 levels higher than the population median experienced improvements in FEV1 and asthma quality of life questionnaire scores 77 RANTES Chemokine at sites of allergic inflammation Serum levels significantly increased in asthma patients vs. controls; and in moderate and severe vs. mild asthma 99 Serum levels correlate positively with absolute eosinophil counts and total serum IgE, and negatively with FEV1 99 Osteopontin Plays a role in Th2‐mediated inflammation Serum levels shown to be elevated in patients with asthma vs. healthy controls, but do not appear to correlate with disease severity 100, 101 Thymus and activation‐regulated chemokine (TARC; CCL17) Thought to be involved in type 2‐mediated inflammation Serum levels shown to be significantly higher in patients with asthma vs. healthy controls and to correlate with eotaxin levels in patients with asthma 102 Serum levels are also increased in other allergic conditions; in particular, atopic dermatitis 103 Appetite‐modulating factors: visfatin and ghrelin Visfatin is an appetite‐modulating pro‐inflammatory adipokine and ghrelin primarily exerts anti‐inflammatory effects Serum levels of visfatin and ghrelin found to be significantly increased in patients with asthma vs. healthy controls 104 Other cytokines and growth factors IL‐3, IL‐18, fibroblast growth factor, hepatocyte growth factor and stem cell growth factor‐β shown to be significantly higher in patients with poorly controlled asthma vs. healthy controls 105 IL‐3 and IL‐18 levels found to be significantly higher in patients with poorly controlled asthma vs. those with well‐controlled asthma 105 Levels of IL‐18, fibroblast growth factor, hepatocyte growth factor and stem cell growth factor‐β shown to correlate positively with poor asthma control and negatively with quality of life scores 105 IL‐23 may be involved in modulating Th17 cells, which are thought to have a pathogenic role in T2 asthma 106 IL‐23 levels found to be significantly higher in children with asthma vs. healthy controls and to have a strong inverse relationship with FEV1 107 Acute‐phase proteins: α(2)‐macroglobulin, haptoglobin, ceruloplasmin and hemopexin Shown to be capable of discriminating between patients with asthma, patients with COPD and healthy controls, using two‐dimensional gel electrophoresis 108 Complement components C3 and C4 Serum levels of C3, but not C4, shown to be elevated in children with stable asthma, with a positive correlation between serum C3 and the severity of asthma 109 Serum levels of C3 and/or C4 found to be elevated in the majority of patients with intermittent atopic asthma vs. healthy controls 110 CRP Non‐specific marker of systemic inflammation that can be routinely measured in clinical practice 111 CRP levels shown to be increased in patients with asthma vs. controls 112 Correlations found between CRP levels and airway obstruction (FEV1/forced vital capacity ratio) 113 and the risk of severe asthma 114 However, CRP is highly non‐specific and has not shown consistent correlation with asthma control 111 Neutrophil chemotaxis velocity Neutrophils obtained from patients with asthma migrate significantly more slowly than those from patients with non‐asthmatic allergic rhinitis 115 Chemotaxis velocity of 1.55 μm/min may represent a threshold that can identify asthma with diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 73%, respectively 115 COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP, C‐reactive protein; DPP‐4, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4; ECP, eosinophil cationic protein; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; IgE, immunoglobulin E; IL, interleukin; RANTES, regulated upon activation, normal T‐cell expressed and secreted; Th2, type 2 helper T cell; T2, type 2. Implications of biomarkers of type 2 inflammation for current clinical practice The management of severe asthma remains a daily challenge as we currently have no gold standard diagnostic test, easy measure of adherence to prescribed therapies or accurate predictor of future risk. Failure to respond to high‐dose inhaled corticosteroids in difficult‐to‐control asthma may either be due to non‐adherence to treatment (which occurs in 30–50% of patients) or may be due to persistent type 2 inflammation, which is relatively resistant to corticosteroid therapy. This latter group of patients requires additional treatment with agents that specifically target type 2 mechanisms (such as anti‐IL‐5 and anti‐IL‐13 treatments) 24. Conversely, patients with severe asthma frequently suffer from multiple comorbidities and may continue to be symptomatic even when their underlying airway inflammation is well controlled. RASP‐UK is currently conducting an objective assessment of corticosteroid adherence in patients with severe asthma and investigating the use of novel biomarker stratification strategies to improve clinical management 24. Specifically, the study will identify patients with high levels of T2 asthma biomarkers (periostin, eosinophils, FeNO) when adherent to high‐dose corticosteroid therapy as appropriate candidates for novel biological treatments that target the T2 cytokine axis 24. It is hoped that such stratification will enable patients to receive the most appropriate treatment, thus optimizing the use of relatively expensive targeted therapies. RASP‐UK will also compare the use of a composite biomarker score, comprising FeNO, serum periostin and blood eosinophils, to guide corticosteroid therapy vs. conventional symptom‐based guidelines, thereby potentially helping to avoid unnecessary morbidity due to excessive corticosteroid exposure 24. U‐BIOPRED (Unbiased BIOmarkers in PREDiction of respiratory disease outcomes) is a 5‐year European‐wide project that aims to identify biomarkers for severe asthma 116. It will make use of multi‐dimensional phenotyping using a series of ‘omics platforms’, in which a large number of parameters will be assessed at one time, allowing researchers to develop a ‘handprint’ of severe asthma subtypes 116. It is hoped that the project will help refine diagnostic criteria for asthma phenotypes and establish whether these can predict responsiveness to new and existing treatments 116, thereby providing a template for asthma stratification and personalization of treatment. Hopefully, these and other ongoing clinical studies will allow the use of blood biomarkers in asthma to move from the research setting to routine clinical practice. The emergence of a multiplicity of novel biomarkers for asthma, including those developed as companion diagnostics for targeted therapies, could lead to confusion and over‐complexity in clinical practice. It is hoped that studies such as RASP‐UK and U‐BIOPRED will provide the strength of data required to enable the development of evidence‐based guidelines detailing how and when specific biomarkers should be used, in terms of guiding prognosis, informing treatment decisions and monitoring subsequent response to therapy. To date, research has predominantly focussed on the characterization of biomarkers for T2 asthma. However, T2 asthma represents only one of the currently recognized asthma phenotypes. Non‐eosinophilic airway inflammation occurs in approximately 50% of patients with asthma, and non‐eosinophilic asthma has been further subdivided into neutrophilic, mixed granulocytic and pauci‐granulocytic (or pauci‐immune) subtypes 30, 117, 118. The proportions of these subtypes are currently unclear, due to variations in the cut‐offs used to define them 117. For example, non‐eosinophilic asthma has been defined as asthma associated with a sputum eosinophil count of either ≤ 2% or ≤ 3%, whilst neutrophilic asthma has been defined using sputum neutrophil cut‐offs ranging from ≥ 60% to > 76% 119. Crucially, non‐eosinophilic asthma is insensitive to corticosteroid therapy 9. To date, biological agents developed to target mediators of non‐eosinophilic inflammation (e.g. IL‐17) and novel small molecules targeting neutrophilic inflammation (e.g. chemokine receptor 2 antagonists) have failed to show convincing beneficial effects in clinical trials 117, 120, 121. There is therefore an ongoing need for research to further identify and characterize biomarkers of non‐T2 asthma, to aid diagnosis, inform prognosis and help guide the development of effective targeted therapies. The characterization of non‐T2 biomarkers is also important for the characterization and management of T2 asthma, as the absence of expression of a T2 biomarker does not necessarily imply a non‐T2 status, and biomarkers for non‐T2 asthma will therefore aid the differential diagnosis of both non‐T2 and T2 phenotypes. Conclusions The clinical management of airway diseases is not straightforward and is confounded by the use of diagnostic labels implying a probable natural history, which can result in suboptimal management paradigms and unhelpfully influence expectations about treatment outcomes 122, 123. Asthma is now known to be heterogeneous with a number of underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, which may require very different treatment approaches. Consequently, there has been an increasing focus on identifying specific, well‐defined and treatable aspects of disease 123, 124. The identification and evidence‐based clinical application of reliable biomarkers that: (1) assist in the diagnosis of asthma, (2) provide prognostic information and (3) identify underlying pathophysiological disease mechanism(s) to target treatment will be major areas of advance in coming years. Several biomarkers are currently available that assist in these areas (Table 3) but ongoing research will help clarify further the potential use of these and other biomarkers in routine practice, and provide greater understanding and evidence for the clinical utility of a range of emerging novel potential biomarkers. Biomarker Ideal characteristics of biomarker Easily measurable Ability to distinguish a mechanism causally linked to important clinical outcome Reliable and reproducible in the clinical setting Ability to provide information about disease prognosis and clinical outcomes Mechanistically linked to the therapeutic target Cost‐effective Bronchial biopsy − ++ − − ++ − Bronchoalveolar lavage − ++ − − ++ − Sputum induction + ++ − +++ + + FeNO ++ ++ +++ ++ ++ ++ VOCs ++ +++ + − ++ ? Exhaled breath condensate +++ + − ++ ++ ? Exhaled breath temperature +++ − − + + +++ Blood eosinophil counts +++ +++ +++ ++ +++ +++ Activation profile of eosinophils + ++ − − +++ ? Serum periostin +++ +++ +++ +++ +++ +++ Chitinase‐like protein YKL‐40 + − − − + ? Blood ILC2s − +++ − ++ ++ ? Serum IgE +++ − − + + ? FeNO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide; IgE, immunoglobulin E; ILC2s, type 2 innate lymphoid cells; VOCs, volatile organic compounds. Acknowledgements Third‐party medical writing assistance for this review paper was provided by John Scopes, mXm Medical Communications, and was funded by Roche Products Ltd. Author contributions All authors were involved in the analysis and interpretation of data included in this article, in the writing of the article and in the decision to submit the article for publication. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version for publication. Conflict of interests In the last 5 years, IDP has received speaker's honoraria from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Aerocrine, Almirall, Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline, and a payment for organizing an educational event from AstraZeneca. He has also received honoraria for attending advisory panels with Almirall, Genentech, Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Schering‐Plough, Novartis, Dey, Napp and Respivert, and sponsorship to attend international scientific meetings from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca and Napp. SA is an employee of Roche Products Ltd. AMG has attended advisory boards for Roche, AstraZeneca, Teva and Novartis; has received lecture fees from Roche, AstraZeneca, Teva, Novartis, Chiesi, Boehringer Ingelheim and Napp; has attended international conferences with Napp and Boehringer Ingelheim; and has participated in clinical trials with GlaxoSmithKline, Roche and Boehringer Ingelheim, for which his institution has been remunerated. LGH has received grant funding from MedImmune, Novartis UK, Hoffmann‐La Roche/Genentech Inc., AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline; has taken part in advisory boards and given lectures at meetings supported by GlaxoSmithKline, Respivert, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Nycomed, Boehringer Ingelheim, Vectura, Novartis and AstraZeneca; has received funding support to attend international respiratory meetings (AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim and GlaxoSmithKline); and has taken part in asthma clinical trials (GlaxoSmithKline, Schering‐Plough, Synairgen and Hoffmann‐La Roche/Genentech), for which his institution was remunerated. He is also Academic Lead for the Medical Research Council Stratified Medicine UK Consortium in Severe Asthma, which involves industrial partnerships with Amgen, Genentech/Hoffman‐La Roche, AstraZeneca, Medimmune, Aerocrine and Vitalograph. References Citing Literature Number of times cited according to CrossRef: 10 G. Roberts, Asthma and oral immunotherapy biomarkers, Clinical & Experimental Allergy, 49, 2, (140-141), (2019). Wiley Online Library Hitasha Rupani and Anoop J Chauhan, Measurement of FeNO in asthma: what the hospital doctor needs to know, British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 10.12968/hmed.2019.80.2.99, 80, 2, (99-104), (2019). Crossref Ian D. Pavord and Nicola A. Hanania, Controversies in Allergy: Should Severe Asthma with Eosinophilic Phenotype Always Be Treated with Anti-IL-5 Therapies, The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.03.010, (2019). Crossref Sun-Hye Lee, Pureun-Haneul Lee, Byeong-Gon Kim, Jisu Hong and An-Soo Jang, Annexin A5 Protein as a Potential Biomarker for the Diagnosis of Asthma, Lung, 10.1007/s00408-018-0159-x, 196, 6, (681-689), (2018). Crossref S. Diver, R. J. Russell and C. E. Brightling, New and emerging drug treatments for severe asthma, Clinical & Experimental Allergy, 48, 3, (241-252), (2018). Wiley Online Library Yunus Çolak, Shoaib Afzal, Børge G. Nordestgaard, Jacob L. Marott and Peter Lange, Combined value of exhaled nitric oxide and blood eosinophils in chronic airway disease: the Copenhagen General Population Study, European Respiratory Journal, 10.1183/13993003.00616-2018, 52, 2, (1800616), (2018). Crossref Lisa Giovannini-Chami, Agnès Paquet, Céline Sanfiorenzo, Nicolas Pons, Julie Cazareth, Virginie Magnone, Kévin Lebrigand, Benoit Chevalier, Ambre Vallauri, Valérie Julia, Charles-Hugo Marquette, Brice Marcet, Sylvie Leroy and Pascal Barbry, The “one airway, one disease” concept in light of Th2 inflammation, European Respiratory Journal, 10.1183/13993003.00437-2018, 52, 4, (1800437), (2018). Crossref Reynold A Panettieri, Ulf Sjöbring, AnnaMaria Péterffy, Peter Wessman, Karin Bowen, Edward Piper, Gene Colice and Christopher E Brightling, Tralokinumab for severe, uncontrolled asthma (STRATOS 1 and STRATOS 2): two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 clinical trials, The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30184-X, 6, 7, (511-525), (2018). Crossref Joo-Hee Kim, Serum vascular endothelial growth factor as a marker of asthma exacerbation, The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine, 32, 2, (258), (2017). Crossref Giovanni Passalacqua, Anti-interleukin 5 therapies in severe asthma, The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 5, 7, (537), (2017). Crossref

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

May 11, 2019 1:51 PM

|

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

April 30, 2019 8:20 AM

|

Many children with asthma think they are using their asthma inhaler medications correctly when they are not. This makes it very difficult to keep their asthma under control. A new study in Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, ...

|

Suggested by

Société Francaise d'Immunologie

April 28, 2019 7:06 AM

|

Original Article from The New England Journal of Medicine — Innate Immunity and Asthma Risk in Amish and Hutterite Farm Children...

|

Suggested by

LIGHTING

April 11, 2019 11:52 PM

|

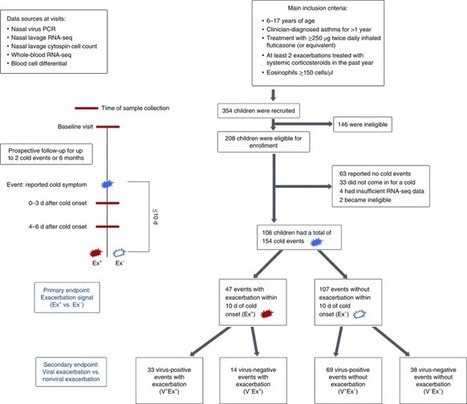

Respiratory infections are the principal cause of asthma exacerbations in children. Altman and colleagues use a systems approach to describe the pathways associated with asthma exacerbations in a cohort of inner-city children.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

March 11, 2019 10:33 AM

|

|

Suggested by

Société Francaise d'Immunologie

March 6, 2019 4:56 AM

|

The neuronal and immune systems exhibit bidirectional interactions that play a critical role in tissue homeostasis, infection, and inflammation. Neuron-derived neuropeptides and neurotransmitters regulate immune cell functions, whereas inflammatory mediators produced by immune cells enhance neuronal activation. In recent years, accumulating evidence suggests that peripheral neurons and immune cells are colocalized and affect each other in local tissues. A variety of cytokines, inflammatory mediators, neuropeptides, and neurotransmitters appear to facilitate this crosstalk and positive-feedback loops between multiple types of immune cells and the central, peripheral, sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric nervous systems. In this Review, we discuss these recent findings regarding neuro-immune crosstalk that are uncovering molecular mechanisms that regulate inflammation. Finally, neuro-immune crosstalk has a key role in the pathophysiology of allergic diseases, and we present evidence indicating that neuro-immune interactions regulate asthma pathophysiology through both direct and indirect mechanisms.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

February 27, 2019 9:31 AM

|

Review Series 10.1172/JCI124610 Influences on allergic mechanisms through gut, lung, and skin microbiome exposures Andrea M. Kemter and Cathryn R. Nagler First published February 25, 2019 - More info In industrialized societies the incidence of allergic diseases like atopic dermatitis, food allergies, and asthma has risen alarmingly over the last few decades. This increase has been attributed, in part, to lifestyle changes that alter the composition and function of the microbes that colonize the skin and mucosal surfaces. Strategies that reverse these changes to establish and maintain a healthy microbiome show promise for the prevention and treatment of allergic disease. In this Review, we will discuss evidence from preclinical and clinical studies that gives insights into how the microbiota of skin, intestinal tract, and airways influence immune responses in the context of allergic sensitization. PREVIEW PAGES Reset NextPage 0Back Continue reading with a subscription. A subscription is required for you to read this article in full. If you are a subscriber, you may sign in to continue reading. Already subscribed? Click here to sign into your account. Don't have a subscription? Please select one of the subscription options, which includes a low-cost option just for this article. At an institution or library? If you are at an institution or library and believe you should have access, please check with your librarian or administrator (more information). Problems? Please try these troubleshooting tips.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

February 14, 2019 5:31 AM

|

Environmental exposures interplay with human host factors to promote the development and progression of allergic diseases. The worldwide prevalence of allergic disease is rising as a result of complex gene-environment interactions that shape the immune system and host response. Research shows an association between the rise of allergic diseases and increasingly modern Westernized lifestyles, which are characterized by increased urbanization, time spent indoors, and antibiotic usage. These environmental changes result in increased exposure to air and traffic pollution, fungi, infectious agents, tobacco smoke, and other early-life and lifelong risk factors for the development and exacerbation of asthma and allergic diseases. It is increasingly recognized that the timing, load, and route of allergen exposure affect allergic disease phenotypes and development. Still, our ability to prevent allergic diseases is hindered by gaps in understanding of the underlying mechanisms and interaction of environmental, viral, and allergen exposures with immune pathways that impact disease development. This Review highlights epidemiologic and mechanistic evidence linking environmental exposures to the development and exacerbation of allergic airway responses.

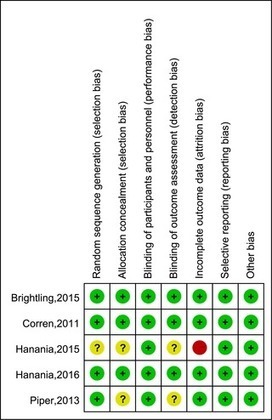

More and more clinical trials have tried to assess the clinical benefit of anti-interleukin (IL)-13 monoclonal antibodies for uncontrolled asthma. The aim of this study is to evaluate the efficacy and safety of anti-IL-13 monoclonal antibodies for uncontrolled asthma. Major databases were searched for randomized controlled trials comparing the anti-IL-13 treatment and a placebo in uncontrolled asthma. Outcomes, including asthma exacerbation rate, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) scores, rescue medication use, and adverse events were extracted from included studies for systematic review and meta-analysis. Five studies involving 3476 patients and two anti-IL-13 antibodies (lebrikizumab and tralokinumab) were included in this meta-analysis. Compared to the placebo, anti-IL-13 treatments were associated with significant improvement in asthma exacerbation, FEV1 and AQLQ scores, and reduction in rescue medication use. Adverse events and serious adverse events were similar between two groups. Subgroup analysis showed patients with high periostin level had a lower risk of asthma exacerbation after receiving anti-IL-13 treatment. Our study suggests that anti-IL-13 monoclonal antibodies could improve the management of uncontrolled asthma. Periostin may be a good biomarker to detect the specific subgroup who could get better response to anti-IL-13 treatments. In view of blocking IL-13 alone is possibly not enough to achieve asthma control because of the overlapping pathophysiological roles of IL-13/IL-4 in inflammatory pathways, combined blocking of IL-13 and IL-4 with monoclonal antibodies may be more encouraging.

Via Krishan Maggon

|

There are no currently available validated biomarkers that can predict AIT success. In adolescents and adults, AIT should be reserved for patients with moderate/severe rhinitis or for those with moderate asthma who, despite appropriate pharmacotherapy and adherence, continue to exhibit exacerbations that appear to be related to allergen exposure, except in some specific cases. Immunotherapy may be even more advantageous in patients with multimorbidity. In children, AIT may prevent asthma onset in patients with rhinitis. mHealth tools are promising for the stratification and follow‐up of patients.

Via Krishan Maggon

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

July 15, 2019 2:29 AM

|

Allergic diseases, such as respiratory, cutaneous and food allergy, have dramatically increased in prevalence over the last few decades. Recent research points to a central role of the microbiome, which is highly influenced by multiple environmental and dietary factors. It is well established that the microbiome can modulate the immune response, from cellular development to organ and tissue formation exerting its effects through multiple interactions with both the innate and acquired branches of the immune system. It has been described at some extent changes in environment and nutrition produce dysbiosis in the gut but also in the skin, and lung microbiome, inducing qualitative and quantitative changes in composition and metabolic activity. Here we review the potential role of the skin, respiratory and gastrointestinal tract microbiomes in allergic diseases.In the gastrointestinal tract, the microbiome has been proven to be important in developing either effector or tolerant responses to different antigens by balancing the activities of Th1 and Th2 cells. In the lung, the microbiome may play a role in driving asthma endotype polarization, by adjusting the balance between Th2 and Th17 patterns. Bacterial dysbiosis is associated with chronic inflammatory disorders of the skin, such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Thus, the microbiome can be considered a therapeutical target for treating inflammatory diseases, such as allergy. Despite some limitations, intervention

|

Suggested by

Société Francaise d'Immunologie

June 8, 2019 1:58 PM

|