Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 24, 10:48 AM

|

RetroVirox has launched a Summer Promotion with a 30% discount for antiviral and neutralization services against 4 viruses, including influenza, dengue, human metapneumovirus (HMPV) and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Discount applies to services initiated between July 1 and August 31 2025

Contact us at info@retrovirox.com for inquiries and additional info

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

Today, 12:19 PM

|

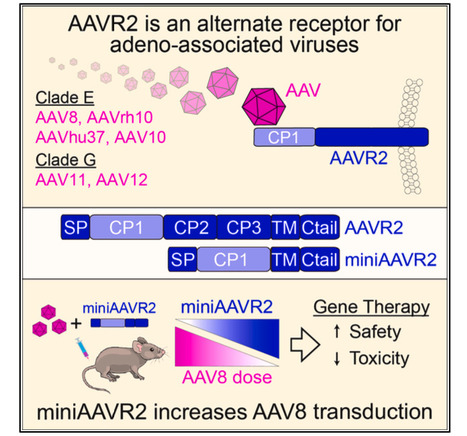

Systemic gene therapy using adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors is approved for the treatment of several genetic disorders, but challenges and toxicities associated with high vector doses remain. We report an alternate receptor for AAV (AAVR2, carboxypeptidase D [CPD]), which is distinct from the multi-serotype AAV receptor (AAVR). AAVR2 enables the transduction of clade E AAVs, including AAV8, and determines an exclusive AAVR-independent transduction pathway for AAV11 and AAV12. We characterized direct binding between the AAV8 capsid and AAVR2 by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and identified contact residues. We observed that AAV8 directly binds to the carboxypeptidase-like domain 1 of AAVR2 via its variable region VIII and demonstrated that AAV capsids that lack AAVR2 binding can be bioengineered to engage with AAVR2. Finally, we overexpressed a minimal functional AAVR2 to enhance AAV transduction in vivo. Our study provides insights into AAV biology and clinically deployable solutions to reduce dose-related toxicities associated with AAV vectors. Published in Cell (July 14, 2025): https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(25)00692-0

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 11, 12:01 PM

|

Cambodia’s Ministry of Health recently confirmed the country’s twelfth human case of H5N1 avian influenza so far this year. The patient, a five-year-old boy from Kampot province, is currently in intensive care with severe respiratory symptoms. The announcement, on July 3, came just days after a 19-month-old child in neighbouring Takeo province died from the same virus. To date, there is no evidence of human-to-human transmission. But the steady increase in cases has renewed attention to the risks posed by H5N1. This highly pathogenic bird flu virus spreads rapidly among poultry and occasionally jumps to humans, often with deadly consequences. Since 2003, there have been at least 954 reported human infections globally, nearly half of them fatal, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). Experts have long considered H5N1 a serious pandemic threat due to its high mortality rate and potential to evolve. The recent Cambodian cases are linked to the 2.3.2.1e lineage of H5N1 (previously known as 2.3.2.1c), a strain that has circulated for decades in poultry across Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. From 2005 to 2014, Cambodia saw sporadic but severe human infections – then almost a decade passed without new cases. That changed in 2023 when six human cases were reported. The numbers have since climbed: ten in 2024, and now 12 in the first half of 2025. Of these recent infections, at least 12 – about 43% – have been fatal. A troubling pattern is also emerging: seven of this year’s cases occurred in June alone, according to the WHO’s latest Disease Outbreak News update. Animal pandemic Globally, however, a different H5N1 lineage – 2.3.4.4b – has dominated in recent years. This strain sparked a devastating wave of avian outbreaks starting in 2021, sweeping across continents and decimating wild bird and poultry populations. It also spread to mammals, leading scientists to label it an “animal pandemic”. Although it no longer causes mass die-offs, 2.3.4.4b remains widespread and dangerous, particularly because of its capacity to infect mammals. It has been linked to about 70 human cases in the US alone, with only one death recorded so far, and is under investigation for suspected mammal-to-mammal transmission in species, including US dairy cattle and seals. Influenza viruses are notoriously prone to genetic reassortment – a process by which two or more strains infect the same host and exchange genetic material. These events can sometimes generate new, more transmissible or deadly variants. In April 2024, the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation reported the emergence of a reassortant virus in Vietnam. This new strain combines surface proteins from the long-standing 2.3.2.1e virus with internal genes from the globally dominant 2.3.4.4b. Evidence suggests that this reassortant virus may be driving the rise in Cambodian human infections. A 2024 study, which has not yet undergone peer review, found that the new virus carries genetic markers that could enhance its ability to infect humans – although it is not yet considered human-adapted. According to the study’s authors, this reassortant form has become the predominant strain found in poultry across the region in recent years. So far, all confirmed human cases in Cambodia have been linked to direct contact with infected or dead poultry – often in small, rural backyards. This suggests that the country’s “one health” strategy, which aims to integrate human, animal and environmental health responses, is functioning as intended. Although some gaps clearly remain. Food safety and food security remain serious concerns across much of Cambodia and Southeast Asia. Limited veterinary oversight, informal poultry markets, lack of compensation for poultry losses due to disease, and poor biosecurity may offer the virus opportunities to persist and evolve – and potentially reach more people. Since the COVID pandemic, advances in disease surveillance and reporting have made it easier to detect and confirm human infections, Dr Vijaykrishna Dhanasekaran, head of the Pathogen Evolution Lab at Hong Kong University, told me over email. However, he notes that surveillance remains heavily concentrated in urban areas and the commercial poultry sector, while rural settings and interactions with wild birds are poorly monitored. Expanding surveillance to these overlooked areas will be vital, he says, if the world hopes to better understand – and prepare for – the next potential influenza pandemic.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 9, 11:42 AM

|

A cancer-killing virus could soon be approved for use after shrinking tumours in a third of people with late-stage melanoma. Despite many decades of effort and numerous human trials, only one virus that is designed to kill cancers has ever been approved by regulators in the US and Europe. But a second could get the green light at the end of the month, after getting good results for treating melanoma, a particularly serious type of skin cancer. A genetically modified herpes virus, called RP1, was injected into the tumours of 140 people with advanced melanoma for whom standard treatments had failed. The participants also took a drug called nivolumab, which is designed to boost the immune response to tumours. In 30 per cent of those treated, tumours shrank, including those that were not injected. In half of these cases, the tumours disappeared altogether. “Half the responders had complete responses, meaning the complete disappearance of all tumours,” says Gino Kim In at the University of Southern California. “We’re very excited about these results.” The other options for treating people at this stage don’t work as well and have more serious side effects, he says. A later-stage trial that will involve 400 people is now under way, but RP1 could be approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US for treating advanced melanoma in combination with nivolumab long before this trial finishes, In told New Scientist. “The FDA is supposed to give us a decision at the end of this month.” It has been known for more than a century that viral infections can sometimes help treat cancers, but deliberately infecting people with “wild” viruses is very risky. In the 1990s, biologists began genetically modifying viruses to try making them better at treating cancers, but unable to harm healthy cells. These viruses are designed to work in two ways. Firstly, by directly infecting cancer cells and killing them by bursting them apart. Secondly, by triggering an immune response that targets all cancerous cells, wherever they are in the body. For instance, a herpes simplex virus known as T-VEC, or Imlygic, was modified to make infected tumour cells release an immune-stimulating factor called GM-CSF, among other changes. In 2015, T-VEC was approved in the US and Europe for treating inoperable melanoma. But T-VEC is not widely used, says In, in part because it was only tested on and approved for injecting into tumours in the skin. Most people with advanced melanoma have deeper tumours, he says. Research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (July 8, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO-25-01346

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 8, 11:48 AM

|

AAP and other leading health organizations allege that the health secretary violated federal law when he took the COVID vaccine off the list of recommended shots for pregnant women and healthy children. A handful of leading medical organizations are suing Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. over recent changes to federal COVID-19 vaccine recommendations — part of what they characterize as a larger effort to undermine trust in vaccines among the American public. The groups behind the complaint, filed on Monday in federal district court, include the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Physicians and the American Public Health Association. The lawsuit centers on Kennedy's decision to remove pregnant women and healthy children from the COVID-19 vaccine schedule in late May. The suit alleges this was "arbitrary" and "capricious" and in violation of federal law that governs how these decisions are made. The complaint asks for the court to reverse the changes to the vaccine recommendations and declare them unlawful. "Over the past several months, experts have been sidelined, evidence has been undermined and our nation's vaccine infrastructure is now threatened," Dr. Susan Kressly, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, told reporters on Monday. "Every child's health is at stake," she said. In a statement to NPR, Andrew Nixon, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services, said, "The Secretary stands by his CDC reforms." The lawsuit was filed in Massachusetts because several of the plaintiffs who've been affected were there, said Richard H. Hughes IV, the lead counsel for the medical groups that are suing the federal government. For example, one of the plaintiffs, identified only as "Jane Doe" in the complaint, is a pregnant physician who works in a hospital in Massachusetts and says she fears she won't be able to get a COVID vaccine. The 42-page complaint catalogues many of Kennedy's actions on vaccine policy since assuming leadership at HHS, including removing the entire roster of experts from a federal vaccine advisory committee and replacing them with his own choices. James Hodge is the director of the Center for Public Health Law and Policy at Arizona State University and is not involved in the lawsuit. Hodge said the case ultimately hinges on the allegations that Kennedy and other leaders of federal health agencies under his purview violated the Administrative Procedure Act, which stipulates how changes in vaccine recommendations should be made. Those changes include a process that involves the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, or ACIP, the panel whose original members Kennedy booted. "The complaint makes a plausible case here that they did not follow proper procedures at all, related to ACIP recommendations," says Hodge. "That's where the court has to take this case seriously."

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 7, 12:04 PM

|

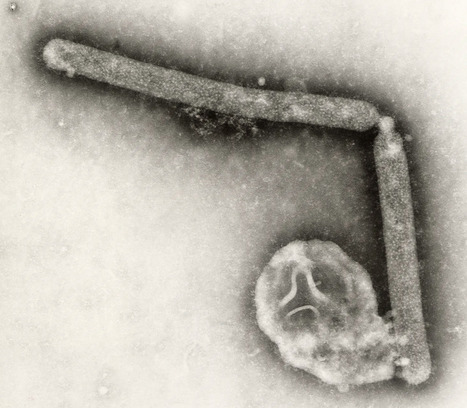

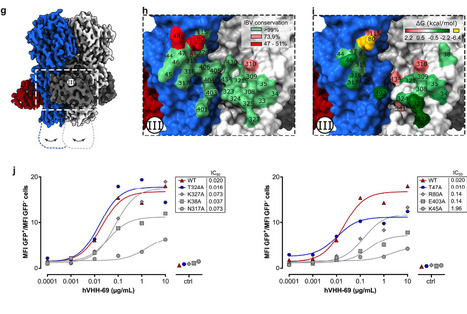

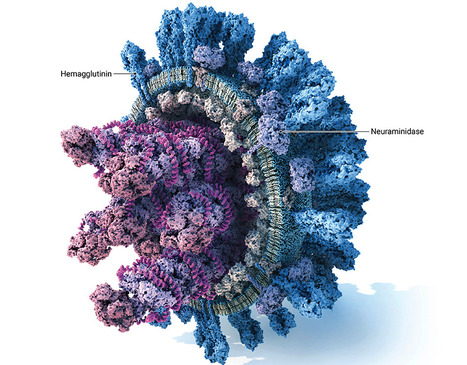

Influenza B viruses are antigenically diverse and contribute significantly to the annual influenza burden. Here we report influenza B virus neutralizing single-domain antibodies that target highly conserved regions of the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. Structural studies by single particle electron cryo-microscopy (cryo-EM) revealed that one of these single-domain antibodies prevents the conformational transition of the viral hemagglutinin to the post-fusion state by targeting a quaternary epitope spanning two protomers in the hemagglutinin-stem region. A second single-domain antibody broadly inhibits influenza B neuraminidase activity, including an oseltamivir-resistant neuraminidase, and its complex with neuraminidase elucidated by single particle cryo-EM established that it binds to residues in the neuraminidase catalytic site. Head-to-tail fusions of these single-domain antibodies led to bispecific binders that further improved the neutralization breadth and potency against influenza B viruses. These single-domain antibodies, fused to a human IgG1-Fc domain, fully protected female mice against an otherwise lethal influenza B virus challenge. Our findings underscore the potential of engineered single-domain antibodies to help control influenza B virus infections. In this study, the authors isolated single-domain antibodies directed against conserved sites of influenza B virus neuraminidase and hemagglutinin and show that they broadly neutralize influenza B viruses and, as IgG Fc fusions, are protective in vivo. Published in Nature Communications (July 1, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60232-3

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 5, 12:14 PM

|

Highly pathogenic avian influenza causes substantial poultry losses and zoonotic concerns globally. Duck vaccination against highly pathogenic avian influenza began in France in October 2023. Our assessment predicted that 314–756 outbreaks were averted in 2023–2024, representing a 96%–99% reduction in epizootic size, likely attributable to vaccination. Our findings suggest the reduction in France’s outbreak numbers in 2023–2024 likely resulted from vaccination, an intervention absent in other countries in Europe. Although general declines in wild bird cases might have reduced environmental contamination, that alone cannot explain the discrepancy in France, because such a trend would be expected elsewhere in Europe. Published in Emerging Infectious Disease (July 2025): https://doi.org/10.3201/eid3107.241445

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 2, 10:58 AM

|

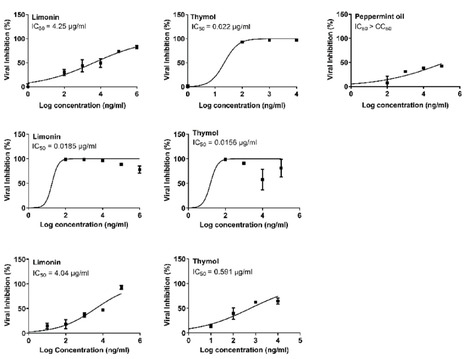

Emerging and re-emerging respiratory viruses represent a continuing threat to human health. The pandemic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) and influenza A viruses (IAVs) are co-circulating, presenting serious threats to public health. Therefore, screening for safe and broad-spectrum antiviral candidates to control such viral infections is prioritized. Herein, this study reports the in vitro antiviral activity of some essential volatile oils (EOs) and volatile oil components including Peppermint oil, Eucalyptus oil, Clove oil, Thymol, Camphor and Limonin against two different IAVs, namely influenza A/H1N1 and A/H5N1 viruses, and SARS-CoV-2 virus. All tested samples were safe in MDCK and Vero E6 cell lines with CC50 values that exceed 1 mg/ml, allowing the screening of their antiviral activities using a wide range of concentrations. The results show the potency of Thymol and Limonin against influenza A/H1N1 virus with IC50 values of 0.022 and 4.25 µg/ml, respectively. The anti-influenza activities of Thymol and Limonin were further validated by testing them against the avian influenza A/H5N1 virus, resulting in anti-influenza activities with IC50 values of 18.5 and 15.6 ng/ml, respectively. The broad-spectrum potential of the highly potent antiviral candidates, Thymol and Limonin, were further tested against the pandemic SARS-CoV-2 and, both exerted anti-coronavirus activities with IC50 values of 0.591 and 4.04 µg/ml, respectively. Further investigations against influenza A/H1N1 virus revealed that Thymol and Limonin could inhibit IAV by hindering viral replication. The Biochemical analyses of the interaction of Limonin and Thymol with FDA-approved anti-influenza drug targets, neuraminidase and viral polymerases, revealed that both compounds can partially inhibit IAV polymerase activity, but have no effect on neuraminidase activity. Likely, molecular docking studies indicated that Thymol and Limonin obstruct active binding sites of IAV polymerases. These findings presented on the antiviral activity of Limonin and Thymol might be used to support the development of supplemental therapy against currently emerging and reemerging respiratory viral infections. Published in Scientific Reports (July 2, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06967-x

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 29, 1:07 PM

|

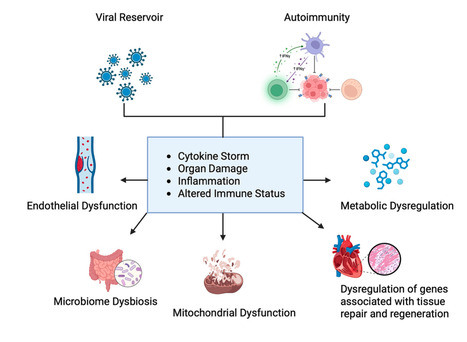

Long coronavirus disease (COVID) is a multisystem condition that affects a significant proportion of individuals following severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, with persistent symptoms ranging from fatigue and cognitive dysfunction to cardiovascular disorders. It is estimated that 30–60% of infected individuals experience symptoms lasting more than 12 weeks. Despite advances in understanding acute infection, the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying long COVID remain unclear. Current hypotheses suggest that viral persistence, immune dysfunction, and metabolic alterations play central roles. Omics approaches, including metabolomics, proteomics, and lipidomics, have played a crucial role in investigating molecular changes, identifying biomarkers, and refining therapeutic strategies. This review discusses recent advances in understanding long COVID, addressing its mechanisms, risk factors, the impact of viral variants, and the role of vaccination, with an emphasis on the importance of omics technologies in elucidating this condition. Published in Molecular Diagnostics and Therapy (June 18 2025): https://doi.org/10.1007/s40291-025-00792-8

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 27, 12:41 PM

|

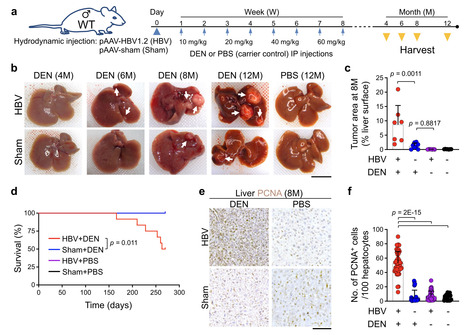

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is associated with hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Considering that most HBV-infected individuals remain asymptomatic, the mechanism linking HBV to hepatitis and HCC remains uncertain. Herein, we demonstrate that HBV alone does not cause liver inflammation or cancer. Instead, HBV alters the chronic inflammation induced by chemical carcinogens to promote liver carcinogenesis. Long-term HBV genome expression in mouse liver increases liver inflammation and cancer propensity caused by a carcinogen, diethylnitrosamine (DEN). HBV plus DEN-activated interleukin-33 (IL-33)/regulatory T cell axis is required for liver carcinogenesis. Pitavastatin, an IL-33 inhibitor, suppresses HBV plus DEN-induced liver cancer. IL-33 is markedly elevated in HBV+ hepatitis patients, and pitavastatin use significantly correlates with reduced risk of hepatitis and its associated HCC in patients. Collectively, our findings reveal that environmental carcinogens are the link between HBV and HCC risk, creating a window of opportunity for cancer prevention in HBV carriers. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is associated with hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Here, the authors show that HBV promotes HCC formation only in response to environmental carcinogens, involving increased IL-33 signaling and regulatory T cells. Published in NAt. Comm. (June 27, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60894-z

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 26, 11:56 AM

|

It is the first NHS England commissioned gene therapy in the UK infused directly into the brain. A three-year-old girl has become the youngest patient in the UK to receive a groundbreaking gene therapy for a rare, life-threatening inherited condition. Gunreet Kaur, from Hayes in west London, underwent the pioneering treatment for aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency, a disorder that severely impacts children’s physical, mental, and behavioural development. Children afflicted with AADC deficiency typically struggle with fundamental bodily controls, including head movement, blood pressure regulation, and heart rate. Gunreet was diagnosed with the condition when she was just nine months old, presenting a significant challenge for her family. However, since receiving the new gene therapy, known as Upstaza, in February 2024, Gunreet has shown remarkable progress. Her mother expressed astonishment at the advancements, which include new movements and vocalisation – milestones she once believed would be unattainable. It is anticipated that Gunreet will continue to make further strides as she grows.The innovative treatment was administered at the world-renowned Great Ormond Street children’s hospital (GOSH) in London. GOSH currently stands as the sole hospital in the UK offering this specific gene therapy to paediatric patients. Sandeep Kaur said Gunreet has made “great progress” since her treatment. “When Gunreet was about seven months old I noticed she wasn’t reaching her milestones at the same age that her older brother did,” she said. “She couldn’t hold her own head up or reach out for items. She cried a lot and always wanted to be held. “Since having the gene therapy, Gunreet has made great progress. “She cries less, smiles more, and can reach for objects. “She can hold her head up and is trying to sit up, she’s recently learned how to roll from her stomach to her back which is fantastic to see. “It means a lot to me that Gunreet was able to have this gene therapy – her general health has improved, she has more co-ordination, she can bring her palms together and is able to move her hand to her mouth.” AADC deficiency is caused by a mutation in the gene that produces the AADC enzyme, this enzyme is needed to produce a neurotransmitter called dopamine which is important in controlling movement. People with AADC deficiency do not have a working version of the enzyme, which means that they have little or no dopamine in the brain. This means that they can suffer developmental delays, weak muscle tone and inability to control the movement of the limbs. It can also lead to painful episodes for affected children. The condition is rare and often deadly, with many children with AADC deficiency not reaching adulthood. The medicine, also known as eladocagene exuparvovec, consists of a virus that contains a working version of the AADC gene. The treatment is delivered by millimetre precision to an exact location in the brain of the patient by a team of medics assisted by a robotic surgery tool. When given to the patient, it is expected that the virus will carry the AADC gene into nerve cells, enabling them to produce the missing enzyme. This is expected to enable the cells to produce the dopamine they need to work properly, which will improve symptoms of the condition. It is the first NHS England commissioned gene therapy in the UK infused directly into the brain. Professor Manju Kurian, consultant paediatric neurologist at GOSH, said “AADC deficiency is a rare condition but often a cruel one that has such a profound impact on children and their carers and families. “We know children with the condition have painful episodes that can last for hours and, as their condition progresses, their life becomes more and more difficult. “It’s incredible to me that I can now prescribe novel gene therapies just as I would prescribe paracetamol and antibiotics. “While the treatment is now available under the NHS at GOSH, we can only do this by working collaboratively across teams inside and outside the hospital, from physios and surgeons to dietitians and speech therapists, alongside partnerships with companies who supply these therapies. “It’s great to see how this treatment has been able to help babies and children across the country like Gunreet. “The natural history of the condition is that most patients cannot fully hold their head or make any developmental progress after that milestone. “Gunreet’s progress over the last year has been really impressive in that context, as well as the virtual disappearance of the eye crises. “We’re hopeful that one day she will be able to talk or walk, as seen in some of the young patients treated in the clinical trial.”

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 23, 11:47 AM

|

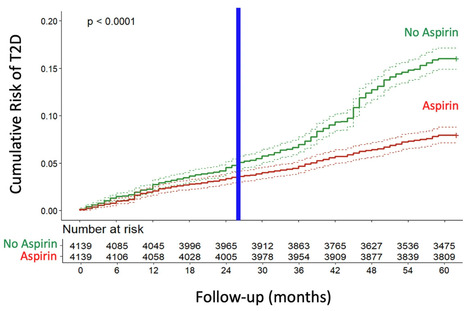

This study aimed to determine whether daily low-dose aspirin reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes (T2D) associated with COVID-19. A longitudinal cohort of 200,000 adults followed from 2018 to 2022 was analyzed, comparing T2D incidence between aspirin users and non-users. Propensity score matching was used to balance the groups. The incidence of T2D was substantially lower in the aspirin group, with Cox regression showing a 52% risk reduction. Kaplan-Meier analysis confirmed a significant divergence in cumulative T2D risk after two years. This protective effect was observed both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a stronger association during the pandemic period. These findings indicate that daily low-dose aspirin significantly reduces the risk of COVID-19-associated new-onset T2D, highlighting the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of T2D triggered or unmasked by COVID-19. Published (June 18, 2025) NPJ Metabolic Health and Disease: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44324-025-00072-3

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 20, 1:02 PM

|

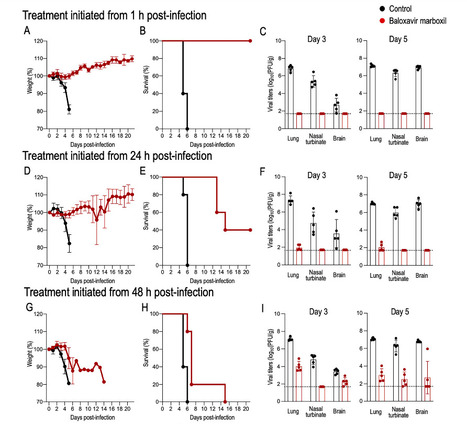

Since the first detection of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 (clade 2.3.4.4b) in U.S. dairy cattle in early 2024, the virus has spread rapidly, posing a major public health concern as the number of human cases continues to rise. Although human-to-human transmission has not been confirmed, experimental data suggest that the bovine H5N1 virus can transmit via respiratory droplets in ferrets, highlighting its pandemic potential. With no vaccines currently available, antiviral drugs remain the only treatment option. Here, we investigate the efficacy of the polymerase inhibitor baloxavir marboxil (BXM) against this virus in mice. We find that early treatment post-infection is effective, but delayed treatment significantly reduces BXM efficacy and increases the risk of BXM resistance, underscoring the importance of timely BXM administration for effective treatment. This study shows that early treatment with baloxavir marboxil is effective against the bovine H5N1 influenza virus, but delayed treatment significantly reduces its effectiveness and increases the risk of emergence of resistant viruses. Published in Nat. Comm (June 20, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60791-5

|

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

Today, 12:34 PM

|

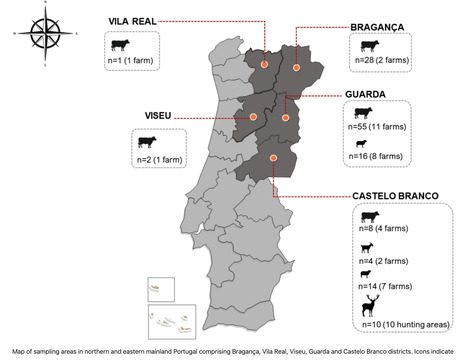

Following the death of an 83-year-old man from the district of Bragança, in north-eastern Portugal due to Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF), a serological survey was conducted to investigate domestic and wild ruminants. The survey included samples from cattle(n = 94), sheep(n = 30), goats(n = 4), and red deer(n = 10) collected within the affected region and neighboring areas where the human case was reported. CCHF antibodies were detected by ELISA in the serum of sheep, cattle and red deer, corresponding to seropositivity rates of 3.33%, 38.29%, and 60%, respectively, indicating significant exposure to the virus. Indirect immunofluorescence assays further validated the ELISA results. Most of the positive cattle originate from farms located in the Guarda district, which are located close to the Spanish border. None of the goats was positive for CCHFV-antibodies and viral-RNA was not detected in any of the samples. CCHFV-RNA was also not detected in 15 ticks from Dermacentor and Rhipicephalus genera collected from vegetation or cattle, on one of the positive farms. Our findings suggest that CCHFV is actively circulating in northeastern Portugal. Reports of human cases of CCHF in Spain, particularly near the border with Portugal, are consistent with the detection of CCHFV-RNA in ticks feeding on domestic and wild animals in western Spain, highlighting the potential for cross-border transmission and suggesting an established circulation of CCHFV in the Iberian Peninsula. Published (July 11, 2025) in Sci. Reports: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10627-5

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 14, 12:03 PM

|

The World Health Organization is now recommending that countries include an HIV drug newly approved for prevention, lenacapavir, as a tool in their efforts to fight HIV infections – especially for groups most at risk and in areas where the burden of HIV remains high. The global recommendation – issued Monday at the International AIDS Conference in Kigali, Rwanda – comes about a month after the US Food and Drug Administration approved lenacapavir as a twice-yearly injection for the prevention of the human immunodeficiency virus or HIV. Lenacapavir had been approved in 2022 to treat certain HIV infections and, in trials for prevention, it was found to dramatically reduce the risk of infection and provide almost total protection against HIV. “These new recommendations are designed for real-world use. WHO is working closely with countries and partners to support the implementation,” Dr. Meg Doherty, director of WHO’s Department of Global HIV, Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections Programmes, said in a news briefing. “The first recommendation is that a long-acting injectable, lenacapavir, should be offered as an additional prevention choice for people at risk for HIV and as part of combination prevention. With that, we call it a strong recommendation with moderate to high certainty of the evidence,” Doherty said. The second recommendation in the guidelines is that rapid diagnostic tests like at-home tests can be used to screen someone for HIV when they are starting, continuing or stopping long-acting medication to prevent infection – called pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP....

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 10, 10:41 AM

|

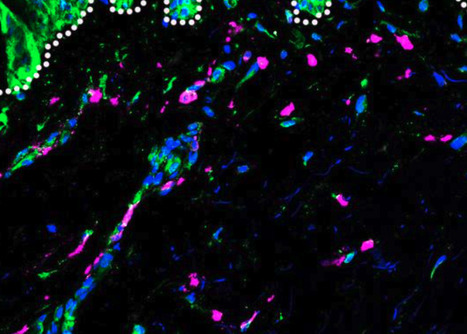

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder with both genetic and environmental factors contributing to pathogenesis. Viral infections are potential environmental triggers that influence PD pathology. Using ViroFind, an unbiased platform for whole virome sequencing, along with quantitative PCR (qPCR), we identified human pegivirus (HPgV) in 5 of 10 (50%) of PD brains, confirmed by IHC in 2 of 2 cases, suggesting an association with PD. All 14 age- and sex-matched controls were HPgV negative. HPgV-brain positive patients with PD showed increased neuropathology by Braak stage and Complexin-2 levels, while those positive in the blood had higher IGF-1 and lower pS65-ubiquitin, supporting disruption in metabolism or mitophagy in response to HPgV. RNA-Seq revealed altered immune signaling in HPgV-infected PD samples, including consistent suppression of IL-4 signaling in both the brain and blood. Longitudinal analysis of blood samples showed a genotype-dependent viral response, with HPgV titers correlating directly with IL-4 signaling in a LRRK2 genotype–dependent manner. YWHAB was a key hub gene in the LRRK2 genotypic response, which exhibited an altered relationship with immune-related factors, including NFKB1, ITPR2, and LRRK2 itself, in patients with PD who are positive for HPgV. These results suggest a role for HPgV in shaping PD pathology and highlight the complex interplay between viral infection, immunity, and neuropathogenesis. Published in JCI Insight (July 8, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.189988

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 8, 12:01 PM

|

uly 7 (Reuters) - The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said on Monday it has ended its emergency response for H5N1 bird flu, owing to a decline in animal infections and no reports of human cases since February. The emergency response was deactivated on July 2, the agency told Reuters, adding that surveillance and response for bird flu cases will continue under the purview of its influenza division. The updates for bird flu was merged with routine updates for seasonal influenza, the agency's website showed on Monday. The number of people monitored and tested for bird flu will be reported on a monthly basis, the agency said, adding that it will no longer report infection rates in animals on its website. The virus has infected 70 people, mostly farm workers, and killed one person over the past year as it spread aggressively among cattle herds and poultry flocks. Experts have warned that further spread of bird flu raises the risk of it becoming more transmissible to humans. The current public health risk from H5N1 bird flu remains low, CDC said, adding that it will continue to monitor the situation and scale up activities as needed. The country's response to bird flu has faced several disruptions this year, including from staff exodus at the U.S. Department of Agriculture as part of the Trump administration's wider efforts to shrink the federal workforce and the government cancelling a more than $700 million contract awarded to Moderna (MRNA.O), opens new tab for the late-stage development of its bird flu vaccine for humans. Bloomberg News first reported that CDC has ended its emergency response, opens new tab for bird flu. Emergency activation allows for additional support for a public health response, including staffing and other resources, to increase testing, surveillance and communications during an outbreak, according to CDC. The CDC H5N1 bird flu response was activated on April 4, 2024.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 7, 12:12 PM

|

Since Spring 2024, new genotypes of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b have been identified in the United States (US). These HPAI H5N1 genotypes have caused unprecedented multi-state outbreaks in poultry and dairy farms, and human infections. Here, we discuss the current situation of this outbreak and emphasizes the need for pre-pandemic preparedness to control HPAI H5N1 in both poultry and dairy farms in the US. Published July 5, 2025: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44298-025-00138-5

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 5, 12:50 PM

|

Most of the locally-acquired cases of chikungunya appear to be clustered around two towns near Marseille, Toulon and Saint-Tropez. A mosquito-borne virus that causes debilitating joint pain and fever has begun to spread locally in holiday hotspots in the South of France. Some 712 imported cases of chikungunya were recorded between May 1 and July 1, leading to 14 locally-acquired infections in the same period, according to data from Santé publique France, the French public health agency. While the disease is routinely brought back to France by returning travellers, the number of imported cases reported this year is greater than the previous ten combined, largely because of a major outbreak on the French Indian Ocean territory of Réunion. Chikungunya is primarily spread by the Aedes mosquito (also known as the tiger mosquito) and cannot spread from person to person. But a mosquito can pick up the disease by feeding on an infected individual and then transmit it to new human hosts by biting them. Most of the locally-acquired cases appear to be clustered around Salon-de-Provence and La Crau, two towns on France’s Mediterranean coast near Marseille, Toulon and Saint-Tropez...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 3, 11:50 AM

|

Gene therapy can improve hearing in children and adults with congenital deafness or severe hearing impairment, a new study involving researchers at Karolinska Institutet reports. Hearing improved in all ten patients, and the treatment was well-tolerated. The study was conducted in collaboration with hospitals and universities in China and is published in the journal Nature Medicine. The study comprised ten patients between the ages of 1 and 24 at five hospitals in China, all of whom had a genetic form of deafness or severe hearing impairment caused by mutations in a gene called OTOF. These mutations cause a deficiency of the protein otoferlin, which plays a critical part in transmitting auditory signals from the ear to the brain. Effect within a month The gene therapy involved using a synthetic adeno-associated virus (AAV) to deliver a functional version of the OTOF gene to the inner ear via a single injection through a membrane at the base of the cochlea called the round window. The effect of the gene therapy was rapid and the majority of the patients recovered some hearing after just one month. A six-month follow-up showed considerable hearing improvement in all participants, the average volume of perceptible sound improving from 106 decibels to 52. Best results in children The younger patients, especially those between the ages of five and eight, responded best to the treatment. One of the participants, a seven-year-old girl, quickly recovered almost all her hearing and was able to hold daily conversations with her mother four months afterwards. However, the therapy also proved effective in adults. "Smaller studies in China have previously shown positive results in children, but this is the first time that the method has been tested in teenagers and adults, too," says Dr Duan. "Hearing was greatly improved in many of the participants, which can have a profound effect on their life quality. We will now be following these patients to see how lasting the effect is." No serious adverse reactions The results also show that the treatment was safe and well-tolerated. The most common adverse reaction was a reduction in the number of neutrophils, a type of white blood cell. No serious adverse reactions were reported in the follow-up period of 6 to 12 months. "OTOF is just the beginning," says Dr Duan. "We and other researchers are expanding our work to other, more common genes that cause deafness, such as GJB2 and TMC1. These are more complicated to treat, but animal studies have so far returned promising results. We are confident that patients with different kinds of genetic deafness will one day be able to receive treatment." The study was conducted in collaboration with a number of institutions, including Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University, China, and was financed by several Chinese research programmes and Otovia Therapeutics Inc., the company that has developed the gene therapy and that employs many of the researchers involved in the study. Research Published in Nature Med. (July 2, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03773-w

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 1, 12:52 PM

|

Skin study findings may help to explain why African ancestry is associated with a lower risk of severe dengue. Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and Instituto Aggeu Magalhães, have for the first time linked the extreme variability in severity of the mosquito-borne viral disease, dengue, between individuals, to the influence of genetic ancestry on inflammatory responses in the skin. The team exposed human skin explants from donors of European or African ancestry to dengue virus (DENV) and examined immune responses. Their findings indicated that inflammatory responses in the skin that promote virus replication and spread are influenced by genetic background, with immune activity increasing with greater European ancestry. The researchers suggest the findings may help to explain why African ancestry is associated with a lower risk of severe dengue, and could point to new approaches to treatments and vaccines for dengue, which is the most common mosquito-borne disease worldwide. Lead author Priscila Castanha, PhD, MPH, assistant professor of infectious diseases and microbiology at Pitt’s School of Public Health, and colleagues reported on their findings in PNAS, in a paper titled “Genetic ancestry shapes dengue virus infection in human skin explants.” The team concluded in their report, “Our findings show that the early innate immune response of human skin to DENV infection is strongly influenced by genetic ancestry…Genetic ancestry should be considered when predicting a patient’s likelihood of severe dengue, and when assessing efficacy and adverse events associated with dengue vaccines.” Cases of dengue fever, commonly known as “breakbone fever” for the excruciating joint pain that is the hallmark of the disease, is the most prevalent arthropod-borne viral disease in humans, affecting tens of millions of people, the authors noted. Cases have been rising around the world in recent years, and more than half the global population is at risk. “There’s an urgent need for better prevention and treatment for this global threat,” said Castanha. “Dengue outbreaks can quickly overwhelm local hospitals.” The course of the disease varies widely from person to person. Some are asymptomatic while others experience dengue’s painful flu-like symptoms and then recover within days or weeks. “But 5% have serious bleeding, shock and organ failure—they can be critically ill within two days,” said senior author Simon Barratt-Boyes, PhD, professor of infectious diseases and microbiology at Pitt Public Health and immunology at Pitt School of Medicine. For decades, epidemiologic studies have documented a puzzling phenomenon. In countries with ethnically diverse populations, people of African ancestry tend to have milder cases of dengue, while people of European ancestry have more severe disease. But no one could explain why. “Beginning more than four decades ago, multiple reports from South and Central American countries with genetically admixed populations described the protective effects of African ancestry from severe dengue,” the authors stated. “African ancestry is associated with protection against severe dengue, but the mechanisms are unknown.” For their newly reported study the team used a model they developed with samples of human skin that had been donated by individuals who had undergone elective skin-reduction surgeries after profound weight loss. “We used skin because it is an immunologic organ and the body’s first line of defense against dengue infection,” said Barratt-Boyes. When maintained in culture under proper conditions, the tissue samples used in this model can survive and carry out their normal immune functions for days, providing a unique opportunity for scientific study, he added, “because the skin is where the story begins with all mosquito-borne diseases.” The study focused on samples from individuals who had self-identified as having European or African ancestry. First, the researchers objectively measured the ancestral geographic origins written into the skin samples’ DNA by analyzing single nucleotide polymorphism genetic markers. The team then injected each skin sample with dengue virus and observed and compared the samples’ subsequent immune responses over a 24-hour period. The team found that the inflammatory response to the virus was much greater in skin from people with higher proportions of European ancestry. And unfortunately, in severe dengue, this immune response is prone to “friendly fire.” The virus infects inflammatory cells, actually recruiting them to spread the infection instead of fighting it off. This dynamic is believed to be what is so damaging to blood vessels and organs in severe cases of dengue fever. In the samples from donors of European ancestry, the team saw this friendly fire in action as myeloid cells mobilized to confront the virus, then themselves became infected. The turncoat cells then moved out of the skin and spread out into the dish—similar to how they would spread within the body, traveling through the bloodstream and into lymph nodes. “We show using isolated human skin specimens that dengue infection elicits a marked inflammatory response in European ancestry skin, leading to infection of resident cells that then migrate out of skin, spreading infection,” the team wrote in summary. “In contrast, African ancestry skin has significantly less inflammation in response to infection, limiting replication and spread.” The protective effects of African ancestry from severe dengue begin at the initial stages of infection, the scientists also note. The team showed that the problem was not the skin itself—it was indeed the inflammatory response. In the samples from individuals with higher proportions of African ancestry, the researchers added inflammatory molecules called cytokines, and the friendly fire ensued. “Infiltration and infection of macrophages in African ancestry skin increased to that of European skin after blocking IFN-α and providing interleukin-1β.” Then, when the team blocked the inflammation within those same samples, the virus’s rate of infection in the cells plummeted. “It makes sense that, in parts of the world where ancient populations were exposed to deadly mosquito-borne viruses—like the one that causes yellow fever, which is related to dengue viruses and has been around for a very long time—those with a limited inflammatory response had an advantage,” said Barratt-Boyes. “They then passed that advantage down to their descendants.” Ancient Europeans’ descendants, however, lack that ancestral exposure and the evolutionary adaptation it made possible. The authors hope that, eventually, the mechanism they’ve identified could be exploited for precision medicine approaches to things like risk assessment, triage in an outbreak, therapies and vaccines. “Genetic ancestry may affect the way different populations respond to dengue vaccines, which are weakened viruses given in skin,” they pointed out. In future studies, the investigators hope to describe this mechanism in further detail, including which specific gene variants contribute to protection from severe dengue. The current study’s broader analysis of geographic ancestry could be an important first step to that end. “Ancestry does affect biology,” said Castanha. “Evolution has made its mark on everyone’s DNA.” Research Published in PNAS (June 30, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2502793122

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 28, 11:31 AM

|

US biomedical agency’s public-access policy kicks in on 1 July. Nature talks to specialists about how to comply. From 1 July, researchers funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) will be required to make their scientific papers available to read for free as soon as they are published in a peer-reviewed journal. That’s according to the agency’s latest public-access policy, aimed at making federally funded research accessible to taxpayers. Established under former US president Joe Biden, the policy was originally set to take effect on 31 December for all US agencies, but the administration of Biden’s successor, Donald Trump, has accelerated its implementation for the NIH, a move that has surprised some scholars. That’s because, although the Trump team has declared itself a defender of taxpayer dollars, it has also targeted programmes and research projects focused on equity and inclusion for elimination. And one of the policy’s main goals is to ensure equitable access to federally funded research. The move means that universities will have less time to advise their researchers on how to comply with the policy, says Peter Suber, director of the Harvard Open Access Project in Cambridge, Massachusetts. There is usually “some confusion or even some non-compliance after a new policy takes effect, but I think universities will eventually get on top of that”, he says. The NIH policy has been welcomed by open-access (OA) advocates, and reflects a global shift towards making publicly funded research freely available. Since 2021, several European science agencies that provide funding for researchers have required grant holders to make their papers OA immediately. What is the new policy? Scientific papers that result from projects funded by the NIH must be deposited in the agency’s digital repository, PubMed Central, and made freely available there immediately after publication in a peer-reviewed journal. Previously, the NIH, the world’s largest public funder of biomedical research, allowed journals to restrict access to papers for an embargo period of up to 12 months before making them publicly available in PubMed Central. The policy applies to manuscripts accepted for publication on or after 1 July, and the version deposited can be either the ‘accepted’ manuscript (including all revisions resulting from the peer-review process) or the final published article. What options do authors have? Scientists can take one of several routes to make their papers immediately free to read. For authors already publishing in an OA journal (or the OA portion of a hybrid journal), the policy brings little change: when researchers’ papers are posted online by the journal, they are made freely available to readers. These authors just need to ensure that their papers are deposited in PubMed Central as soon as they are published. And “if you’re publishing open access, a lot of those publishers have mechanisms in place to do the deposit for you”, says Lisa Hinchliffe, a librarian and academic at the University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign. Authors publishing in closed-access journals (or the closed sections of hybrid journals), which require people to have a subscription to read papers, will be most affected by the change, Hinchliffe says. Researchers will have to make sure that the agreement they sign with the publisher complies with the NIH policy, meaning that they are allowed to deposit the full version of the paper in PubMed Central without embargo. They might also need to submit the paper to PubMed Central themselves, because some publishers have indicated that they will not offer this service. What issues might researchers encounter? Several publishers, including Elsevier and Springer Nature, require that papers published in closed-access journals remain available only to subscribers for an embargo period — 6 or 12 months, for instance — before they can be placed in repositories such as PubMed Central (Nature’s news team is editorially independent of its publisher, Springer Nature). “It’s very likely that not all publisher agreements will be compatible with the new policy, and that creates a difficult situation — both for the publisher and for the author,” Suber says. These publishers might steer authors towards their OA journals (or the OA parts of their hybrid journals) to comply with the policy. However, OA journals make their money by asking for article-processing charges (APCs), which can be anywhere from hundreds to thousands of dollars. Authors switching to publishing in an OA journal would be responsible for paying those APCs. This is what happened when Plan S — an OA initiative launched by a coalition of mostly European funders — went into effect, Hinchliffe says. “Authors should know that in advance, and if they don’t want to pay the APC, but still want to comply with the NIH policy, then they have to go somewhere else,” Suber says. Some authors might not need to worry about APCs, however. In preparation for the NIH policy coming into effect, some universities have been putting in place agreements with publishers that allow their researchers to publish OA papers at no cost to them, generally through contracts where universities shift funds previously spent on subscriptions to supporting OA publishing. The Big Ten Academic Alliance, a consortium of US research universities, announced one such agreement with Springer Nature last month. Not only are we prepared for the transition to OA, says Maurice York, director of Library Initiatives for the Big Ten alliance, but “it’s what we’ve been pushing for”. Furthermore, some funders cover APCs. According to the NIH’s policy, the agency will allow authors to include ‘reasonable costs’ associated with publication, such as APCs, in their project budgets....

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 27, 12:22 PM

|

Thimerosal is found in only a small fraction of US vaccine doses but has long been viewed with suspicion by the anti-vaccination community. Vaccine advisers appointed by US health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr have recommended against the use of influenza vaccines containing a mercury-based preservative called thimerosal — fulfilling a long-held goal of the anti-vaccine movement. The vote’s practical effects in the United States are limited, because most US flu vaccine doses are already free of thimerosal, which is only present in multi-dose vials, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). And the ingredient was removed from all childhood vaccines in 2001. But thimerosal has long been a target of the anti-vaccine movement, despite strong evidence supporting its safety in the low doses found in vaccines. Public-health officials and scientists say that the vote’s symbolic effects are powerful as they struggle to maintain public confidence in vaccines. “We are talking about such a small amount of vaccine” containing thimerosal, says Chrissie Juliano, executive director of Big Cities Health Coalition, an association of US health departments, in Takoma Park, Maryland. “What this does is sow mistrust. It confuses the public.” “It was an anti-science recommendation,” says Paul Offit, the director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania. “We have the information we need to tell us that thimerosal, at the level contained in vaccines, is a trivial contribution to the mercury that we’re exposed to every day.” The US Department of Health and Human Services, which includes the CDC, did not respond to a request for comment by publication time. Handpicked panel The decision came today during the first meeting of the newly chosen Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), a panel that recommends which vaccines US residents should receive and when. Most US health-insurance programmes, which fund health care for US residents, are required to provide vaccines recommended by the ACIP at no cost. Earlier this month, Kennedy, a vaccine sceptic, fired all 17 members of the committee and appointed 8 new ones, some of whom have expressed scepticism about vaccines. (One new member stepped down shortly before the meeting.) Before the vote, the committee heard a presentation by Lyn Redwood, a nurse practitioner and president emeritus of the anti-vaccine group Children's Health Defense in Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, founded by Kennedy. She advocated for the removal of the ingredient from US vaccines, pointing to various studies to make her case. Offit, who is a former member of the ACIP, says that subject-matter experts typically vet presentations before the meeting — a step that was not followed in this case — and probably would have flagged some of the data Redwood presented as inaccurate. A version of Redwood’s slides posted before the meeting contained a reference to a paper that doesn't exist, according to Reuters. The reference was later removed. Some members of the committee echoed Redwood’s claims about the safety of thimerosal, but member Cody Meissner, a paediatrics researcher at the Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine in Lebanon, New Hampshire, criticized the meeting’s focus on thimerosal. “I’m not quite sure how to respond to this presentation. This is an old issue that has been addressed in the past,” he said. “Of all the issues that ACIP needs to focus on, this is not a big issue,” he added. His was the only dissenting vote on the recommendation against thimerosal-containing vaccines. Meissner expressed concerns that the ACIP’s recommendation could impact access to vaccines in other countries. “The recommendations that the ACIP makes are followed among many countries around the world,” he noted, and removing thimerosal from all vaccines could increase costs. Multi-dose vials, which are the ones that still contain the ingredient, are generally cheaper and easier to store and use in mass vaccination programs.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 25, 11:21 AM

|

Influenza vaccines could soon get some serious competition—or assistance. A new clinical trial shows a single shot of a long-lasting flu drug may protect people for an entire season, and it might do so more effectively than vaccines. In a study that enrolled 5000 healthy adults before the flu season started and followed them until after it ended, the highest dose of the drug provided 76.1% protection from disease, compared with a placebo shot, its developer, Cidara Therapeutics, reported in a press release and on an investor call yesterday. “This is one of the most exciting recent advances for influenza prevention,” says Kathleen Neuzil, a veteran influenza vaccine researcher recently forced out of her job as head of the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health by President Donald Trump’s administration. The drug’s promise echoes that of the anti-HIV drug lenacapavir, which protects people from infection for 6 months and last week won approval from the Food and Drug Administration as a so-called pre-exposure prophylactic. Called CD388, the flu shot contains a reformulated version of zanamivir, a flu drug also known as Relenza that GSK brought to market in 1999 and is approved to both treat and prevent disease. Zanamivir, which must be inhaled daily, targets neuraminidase, an enzyme made by the virus that frees newly made virions from the surface of infected cells. To create a longer lasting version, Cidara developed a chemical variant of the drug and attached several copies of it to a piece of an antibody called the Fc fragment, which is engineered to resist being broken down by the human body. The study, which took place in the United States and the United Kingdom, recruited adults who had not received the influenza vaccine. They were given one of three different doses of CD388 or a placebo shot under the skin between September and December 2024. Over the next 24 weeks, the researchers tallied the number of participants who had respiratory symptoms, such as coughing and a fever, and a confirmed test for the influenza virus. All three doses provided what Cidara’s chief medical officer, Nicole Davarpanah, described as “highly statistically significant protection,” although the lowest had only 57.7% efficacy and the middle dose 61.3%. No serious side effects occurred at any dose. Seasonal influenza vaccines, which are given either by injection or as a nasal spray, are designed to protect against at least three of the seasonal strains that circulate each winter. Their effectiveness at preventing disease depends heavily on how well they match the flu strains going around in the human population but average only about 40% because mutations in flu viruses often allow them to dodge immune responses. In contrast, CD388 is effective against a wide variety of strains, a study in mice published by Cidara researchers the 17 March issue of Nature Microbiology shows. The drug attacks a region of neuraminidase that cannot easily change without compromising viral fitness. But Neuzil cautions that although resistance to neuraminidase inhibitors is rare in flu viruses, it does occur, and Cidara’s press release did not address the issue. “This would be important to follow,” she says. Epidemiologist Arnold Monto of the University of Michigan School of Public Health says he anticipated Cidara’s positive results, based on a study he helped conduct more than 25 years ago. Inhaling zanamivir every day during the flu season offered 84% protection, Monto and his co-workers reported in JAMA in 1999. Those findings went nowhere because most people don’t want to take a daily drug to prevent the flu, Monto says. But a single injection may attract a large market. “This strategy is very attractive in many ways,” he says. Monto adds that much will depend on the drug’s future price, which the company did not want to discuss. “Flu vaccines are very cheap,” he notes. And several research groups are working to develop “universal” flu vaccines that work against virtually all strains and pack more punch than existing ones. Other drugs to prevent influenza are also in the works, including one being made by Cerberus Therapeutics that delivers zanamivir via “nanobodies”—tiny antibodies derived from camels that are relatively easy to produce in massive quantities—says immunologist and Cerberus Co-Founder Hidde Ploegh. Although he calls CD388 a “valuable approach” and the new data “compelling,” Ploegh believes Cerberus will have an advantage because its drug is squirted up the nose. “If you think of ease of distribution, compliance, and acceptance, then I think any approach that avoids needles is preferable,” he says. Then again Cerberus has yet to reach human studies. Cidara plans to launch large-scale efficacy trials of CD388 in the Southern Hemisphere’s flu season, which starts in early 2026. Those studies will allow participants to also get vaccinated against flu, if they want; the two interventions combined could offer even better protection. The trial will focus on people with compromised immune systems or chronic conditions that make them particularly vulnerable to severe influenza. “If the inhibitor can be manufactured at a large scale at a reasonable price, it could be very helpful as a prophylaxis for high-risk people,” says flu research Adolfo García-Sastre of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “It’s a very interesting technology.”

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 20, 1:25 PM

|

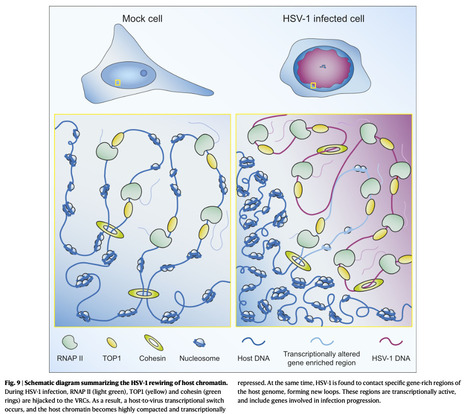

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) remodels the host chromatin structure and induces a host-to-virus transcriptional switch during lytic infection. We combine super-resolution imaging and chromosome-capture technologies to identify the mechanism of remodeling. We show that the host chromatin undergoes massive condensation caused by the hijacking of RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) and topoisomerase I (TOP1). In addition, HSV-1 infection results in the rearrangement of topologically associating domains and loops, although the A/B compartments are maintained in the host. The position of viral genomes and their association with RNAP II and cohesin is determined nanometrically. We reveal specific host–HSV-1 genome interactions and enrichment of upregulated human genes in the most contacting regions. Finally, TOP1 inhibition fully blocks HSV-1 infection, suggesting possible antiviral strategies. This viral mechanism of host chromatin rewiring sheds light on the role of transcription in chromatin architecture. Here, the authors show how HSV-1 rewires the host cell’s chromatin architecture during lytic infection by hijacking transcription machinery and forming contacts between viral and host genomes. Published in Nature Comm. (June 19, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60534-6

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...