Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

January 21, 2024 12:25 PM

|

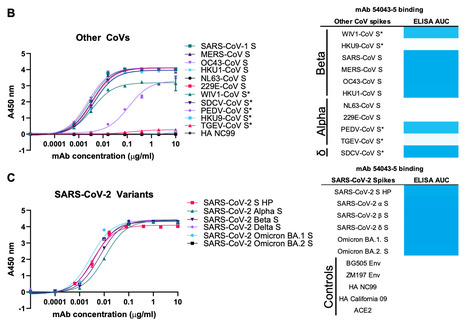

Three coronaviruses have spilled over from animal reservoirs into the human population and caused deadly epidemics or pandemics. The continued emergence of coronaviruses highlights the need for pan-coronavirus interventions for effective pandemic preparedness. Here, using LIBRA-seq, we report a panel of 50 coronavirus antibodies isolated from human B cells. Of these antibodies, 54043-5 was shown to bind the S2 subunit of spike proteins from alpha-, beta-, and deltacoronaviruses. A cryo-EM structure of 54043-5 bound to the pre-fusion S2 subunit of the SARS-CoV-2 spike defined an epitope at the apex of S2 that is highly conserved among betacoronaviruses. Although non-neutralizing, 54043-5 induced Fc-dependent antiviral responses, including ADCC and ADCP. In murine SARS-CoV-2 challenge studies, protection against disease was observed after introduction of Leu234Ala, Leu235Ala, and Pro329Gly (LALA-PG) substitutions in the Fc region of 54043-5. Together, these data provide new insights into the protective mechanisms of non-neutralizing antibodies and define a broadly conserved epitope within the S2 subunit. Pre-print in bioRxiv (Jan. 16, 2024): https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.01.15.575741

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

November 21, 2022 11:14 AM

|

A new discovery in the fight against COVID could lead to a long-lasting vaccine that works on all variants of the ever-mutating virus. With new COVID variants and subvariants evolving faster and faster, each chipping away at the effectiveness of the leading vaccines, the hunt is on for a new kind of vaccine—one that works equally well on current and future forms of the novel coronavirus. Now researchers at the National Institutes of Health in Maryland think they’ve found a new approach to vaccine design that could lead them to a long-lasting jab. As a bonus, it also might work on other coronaviruses, not just the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19. The NIH team reported its findings in a peer-reviewed study that appeared in the journal Cell Host & Microbe earlier this month. The key to the NIH’s potential vaccine design is a part of the virus called the “spine helix.” It’s a coil-shaped structure inside the spike protein, the part of the virus that helps it grab onto and infect our cells. Lots of current vaccines target the spike protein. But none of them specifically target the spine helix. And yet, there are good reasons to focus on that part of the pathogen. Whereas many regions of the spike protein tend to change a lot as the virus mutates, the spine helix doesn’t. That gives scientists “hope that an antibody targeting this region will be more durable and broadly effective,” Joshua Tan, the lead scientist on the NIH team, told The Daily Beast. Vaccines that target and “bind,” say, the receptor-binding domain region of the spike protein might lose effectiveness if the virus evolves within that region. The great thing about the spine helix, from an immunological standpoint, is that it doesn’t mutate. At least, it hasn’t mutated yet, three years into the COVID pandemic. So a vaccine that binds the spine helix in SARS-CoV-2 should hold up for a long time. And it should also work on all the other coronaviruses that also include the spine helix—and there are dozens of them, including several such as SARS-CoV-1 and MERS that have already made the leap from animal populations and caused outbreaks in people. To test their hypothesis, the NIH researchers extracted antibodies from 19 recovering COVID patients and tested them on samples of five different coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-1 and MERS. Of the 55 different antibodies, most zeroed in on parts of the virus that tend to mutate a lot. Just 11 targeted the spine helix. But those 11 that went after the spine helix worked better, on average, on four of the coronaviruses. (A fifth virus, HCoV-NL63, shrugged off all the antibodies.) The NIH team isolated the best spine-helix antibody, COV89-22, and also tested it on hamsters infected with the latest subvariants of the Omicron variant of COVID. “Hamsters treated with COV89-22 showed a reduced pathology score,” the team found. The results are promising. “These findings identify a class of… antibodies that broadly neutralize [coronaviruses] by targeting the stem helix,” the researchers wrote. Don’t break out the champagne quite yet. “Although these data are useful for vaccine design, we have not performed vaccination experiments in this study and thus cannot draw any definitive conclusions with regard to the efficacy of stem helix-based vaccines,” the NIH team warned. It’s one thing to test a few antibodies on hamsters. It’s another to develop, run trials with and get approval for a whole new class of vaccine. “It is really hard and most things that start out as good ideas fail for one reason or another,” James Lawler, an infectious disease expert at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, told The Daily Beast. And while the spine-helix antibodies appear to be broadly effective, it’s unclear how they stack up against antibodies that are more specific. In other words, a spine-helix jab might work against a bunch of different but related viruses, but work less well against any one virus than a jab that’s tailored specifically for that virus. “Further experiments need to be done to evaluate if they will be sufficiently protective in humans,” Tan said of the spine-helix antibodies. There’s a lot of work to do before a spine-helix vaccine might be available at the corner pharmacy. And there are a lot of things that could derail that work. Additional studies could contradict the NIH team’s results. The new vaccine design might not work as well on people as it does on hamsters. The new jab could also turn out to be unsafe, impractical to produce or too expensive for widespread distribution. Barton Haynes, a Duke University immunologist, told The Daily Beast he looked at spine-helix vaccine designs last year and concluded they’d be too costly to warrant major investment. The main problem, he said, is that the spine-helix antibodies are less potent and “tough to induce” from their parent B-cells. The harder the pharmaceutical industry has to work to produce a vaccine, and the more vaccine it has to pack into a single dose in order to compensate for lower potency, the less cost-effective a vaccine becomes for mass-production. Maybe a spine-helix jab is in our future. Or maybe not. Either way, it’s encouraging that scientists are making incremental progress toward a more universal coronavirus vaccine. One that could work for many years on a wide array of related viruses. COVID for one isn’t going anywhere. And with each mutation, it risks becoming unrecognizable to the current vaccines. What we need is a vaccine that’s mutation-proof. Publication cited published in Cell Host and Microbe (Nov. 7, 2022): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2022.10.010

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

August 19, 2021 1:43 AM

|

Dramatic antibody production in people that were infected during the 2002–04 outbreak furthers hopes of a vaccine against many coronaviruses. People who were infected almost two decades ago with the virus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) generate a powerful antibody response after being vaccinated against COVID-19. Their immune systems can fight off multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants, as well as related coronaviruses found in bats and pangolins. The Singapore-based authors of a small study published today in The New England Journal of Medicine1 say the results offer hope that vaccines can be developed to protect against all new SARS-CoV-2 variants, as well as other coronaviruses that have the potential to cause future pandemics. The study is a “proof of concept that a pan-coronavirus vaccine in humans is possible”, says David Martinez, a viral immunologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “It’s a really unique and cool study, with the caveat that it didn’t include many patients.” SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the sarbecovirus group of coronaviruses, which includes the virus that caused SARS (called SARS-CoV), as well as closely related bat and pangolin coronaviruses. Sarbecoviruses use what are known as spike proteins to bind to ACE2 receptors in the membranes of host cells and enter them. They can jump from animals to humans, as they did before in both the current pandemic and the 2002–04 outbreak of SARS, which spread to 29 countries. “The fact that this has happened twice in the last two decades is strong rationale that this is a group of viruses that we really need to pay attention to,” says Martinez. Neutralizing antibodies Last year, Linfa Wang, a virologist at Duke–NUS Medical School in Singapore who led the latest study, went looking for people who had survived SARS to see whether they offered any clues about how to develop vaccines and drugs for COVID-19. He detected ‘neutralizing’ antibodies in their blood that blocked the original SARS virus from entering cells, but did not affect SARS-CoV-2 — which he found surprising, because the viruses are closely related. But when Singapore rolled out the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine this year, Wang decided to interrogate how the SARS infection affected responses to the vaccine. What he discovered was striking. Eight vaccinated study participants, who had recovered from SARS almost two decades ago, produced very high levels of neutralizing antibodies against both viruses, even after just one dose of the vaccine. They also produced a broad spectrum of neutralizing antibodies against three SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in the current pandemic — Alpha, Beta and Delta — and five bat and pangolin sarbecoviruses. No such potent and wide-ranging antibody response was observed in blood samples taken from fully vaccinated individuals, even those who had also had COVID-19. The researchers suggest that such broad protection could arise because the vaccine jogs the immune system’s ‘memory’ of regions of the SARS virus that are also present in SARS-CoV-2, and possibly many other sarbecoviruses. Coronaviruses found in bats have the potential to cause future pandemics, so the fact that a broad spectrum of neutralizing antibodies is generated that protects against some of them “is encouraging”, says Daniel Lingwood, an immunologist at the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard in Boston. But researchers say it is not clear how long this protection lasts. A vaccine that is widely effective against sarbecoviruses could be administered to the general population in high-risk areas close to animals that harbour them, limiting the potential spread of these viruses in people, adds Christopher Barnes, a structural biologist at Stanford University in California. Which part of the virus Barton Haynes, an immunologist at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina, says the study raises the question of whether a similar response could be generated if people vaccinated against COVID-19 were given a booster shot that targeted the original SARS virus. This might protect them against new variants of SARS-CoV-2 and other sarbecoviruses. Wang says preliminary studies in mice suggest that is possible. But the latest study doesn’t identify exactly which sections of the viruses induce the broad immune response, something that would be needed to develop vaccines. That’s the “biggest question”, says Martinez. If it is a region of the virus that is present not just in sarbecoviruses, but in the entire group of coronaviruses, there is potential for creating a vaccine against all of them, he says. Several research groups have identified specific antibodies that prevent SARS-CoV-2 and other sarbecoviruses from spreading in cells. Others are already working on pan-coronavirus vaccines, and have synthesized components that induce strong protection in monkeys and mice. Haynes and his colleagues, for example, have developed2 a protein nanoparticle studded with 24 pieces of a section of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein called the receptor binding domain, a key target of antibodies. They found that in monkeys, the nanoparticle induced much higher levels of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 than did the Pfizer vaccine. It also induced cross-reactive antibodies against the original SARS virus and bat and pangolin sarbecoviruses. Martinez and his colleagues have induced these widely reactive antibodies in mice, using a vaccine made from a combination of spike proteins from different coronaviruses3. But Martinez says the latest study suggests that this complex spike chimaera might not be necessary; a similar protective response could be induced simply by the original SARS virus’s spike protein. Wang says he is already working on potential vaccines that target multiple sarbecoviruses, and he now hopes to find additional survivors of the 2002–04 SARS outbreak to conduct a much larger study, including testing their responses to other COVID-19 vaccines. Research Cited Published in NEJM (Aug. 18, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2108453

|

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

March 19, 2023 1:27 PM

|

In a recent article published in the journal PNAS, researchers in China provide evidence that a novel vaccine candidate known as CF501/RBD-Fc robustly neutralized severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Omicron subvariants BQ.1.1 and XBB in a rhesus macaque animal model. This vaccine comprised the human immunoglobulin G (hIgG) fraction, crystallizable (Fc)-conjugated receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 ancestral WA1 strain, in combination with a novel stimulator of interferon genes (STING) agonist-based adjuvant called CF501. The study findings confirm that CF501/RBD-Fc induced highly potent and persistent broad-neutralizing antibody (bnAb) responses against several SARS-CoV-2 variants, including Omicron subvariants. Background Due to their exceptional immune-evasion properties, Omicron subvariants pose a significant challenge to current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines. For example, the BA.5 subvariant is resistant to neutralization, even after four doses of a messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccine. Moreover, the newly emerged XBB Omicron subvariant remains unneutralized by nAbs induced by a booster dose of the bivalent vaccine containing the mRNA sequences of the Omicron BA.5 and ancestral spike (S) proteins. Previous studies using the pseudovirus neutralization assay have shown that, as compared to the ancestral strain D614G, XBB is up to 155-fold more resistant to nAbs in vaccinee sera. Thus, there remains an urgent need for a pan-sarbecovirus vaccine with the ability to neutralize current and yet-to-emerge SARS-CoV-2 variants. About the study In the present study, researchers administered three doses of CF501/RBD-Fc or Alum/RBD-Fc-based vaccines in two groups, each comprised of three rhesus macaques. Sera was subsequently collected to evaluate RBD-binding IgG and nAb titers through the use of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and virus neutralization assays. The researchers also tested whether sera from immunized rhesus macaques could neutralize pseudotyped Omicron subvariants. Each test animal's parameters were correlated by pairwise comparisons to assess the association between nAb and binding antibodies specific to Omicron subvariants XBB and BQ.1.1. Results At day 28, after two vaccine doses, endpoint RBD-specific IgG titers against Omicron subvariants in the CF501/RBD-Fc group ranged between 512,000 and 1,792,000. These values were nearly three- to 28-fold higher than that of the Alum/RBD-Fc group. Although the endpoint titers gradually declined, they remained relatively stable and higher in the CF501/RBD-Fc group as compared to the Alum/RBD-Fc group. The magnitude of the RBD-binding antibodies remained consistently higher in the CF501/RBD-Fc group after three vaccine doses and remained high until day 191 following the first vaccination. The 50% neutralizing titers (NT50) of bnAbs in sera from CF501/RBD-Fc macaques were much higher than those in the Alum/RBD-Fc group against all pseudotyped viruses, with NT50 values of 436 and 313 against BQ.1.1 and XBB at day 28, respectively. Cross-neutralizing bnAb titers in the CF501/RBD-Fc group continued to increase after the third vaccination, with day 122 NT50 values of 2,118 and 2,526 against BQ.1.1 and XBB after receipt of the first vaccine dose, respectively. These titers also increased in the Alum/RBD-Fc group after three vaccine doses; however, these values marginally surged against BQ.1.1 and XBB. Eventually, NT50 values declined in both groups. The third vaccine dose did not elicit increased NT50 titers against D614G but drastically increased bnAb titers against the Omicron subvariants. Although their NT50 against BQ.1.1 and XBB declined by 26.9- and 22.5-fold relative to D614G, respectively, these bnAbs effectively neutralized BQ.1.1 and XBB infection. Virus neutralization assay results also showed that CF501/RBD-Fc sera potently neutralized authentic BA.2.2 infection as compared to Alum/RBD-Fc sera. Immunofluorescence assay also confirmed that sera from CF501/RBD-Fc group potently inhibited Omicron BA.2.2 replication. Conclusions Overall, the study findings indicate that the CF501 adjuvant stimulated the conservative but nondominant RBD epitopes for generating bnAbs against pan-sarbecovirus vaccines. Thus, the researchers recommend replacing the adjuvant in the first-generation COVID-19 subunit vaccines with CF501 for next-generation booster vaccinations. This strategy might enhance the immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants BQ.1.1 and XBB, as well as future SARS-CoV-2 variants that have yet to emerge. Research cited published (March 10, 2023) in PNAS: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2221713120

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 29, 2022 11:20 AM

|

Germany's BioNTech , Pfizer's partner in COVID vaccines, said the two companies would start tests on humans of next-generation shots that protect against a wide variety of coronaviruses in the second half of the year. Their experimental work on shots that go beyond the current approach include T-cell-enhancing shots, designed to primarily protect against severe disease if the virus becomes more dangerous, and pan-coronavirus shots that protect against the broader family of viruses and its mutations. In presentation slides posted on BioNTech's website for its investor day, the German biotech firm said its aim was to "provide durable variant protection". The two partners, makers of the Western world's most widely used COVID-19 shot, are currently discussing with regulators enhanced versions of their established shot to better protect against the Omicron variant and its sublineages. read more The virus' persistent mutation into new variants that more easily evade vaccine protection, as well as waning human immune memory, have added urgency to the search by companies, governments and health bodies for more reliable tools of protection. As part of a push to further boost its infectious disease business, BioNTech said it was independently working on precision antibiotics that kill superbugs that have grown resistant to currently available anti-infectives. BioNTech, which did not say when trials could begin, is leaning on the technology of PhagoMed, which it acquired in October last year. The Vienna-based antibiotics developer has done work on enzymes, made by bacteria-killing viruses, that break through the bacterial cell wall. Drug-resistant infections are on the rise, driven by antibiotic overuse and leaks into the environment in antibiotics production. Public health researchers put the combined number of people dying per year from antibiotic-resistant infections in the United States and the European Union at close to 70,000. read more

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

April 17, 2021 12:06 PM

|

n 2017, three leading vaccine researchers submitted a grant application with an ambitious goal. At the time, no one had proved a vaccine could stop even a single beta coronavirus—the notorious viral group then known to include the lethal agents of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), as well as several causes of the common cold and many bat viruses. But these researchers wanted to develop a vaccine against them all. Grant reviewers at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) deemed the plan “outstanding.” But they gave the proposal a low priority score, dooming its bid for funding. “The significance for developing a pan-coronavirus vaccine may not be high,” they wrote, apparently unconvinced that the viruses pose a global threat. How things have changed. As the world nears 3 million deaths from the latest coronavirus in the spotlight, SARS-CoV-2, NIAID and other funders have had a major change of heart. In November 2020, the agency solicited applications for “emergency awards” to pursue pancoronavirus vaccine development. And in March, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), an international nonprofit launched in 2017, announced it would spend up to $200 million on a new program to accelerate the creation of vaccines against beta coronaviruses, a family that now includes SARS-CoV-2. The threat of another coronavirus pandemic now seems very real. Beyond bats, coronaviruses infect camels, birds, cats, horses, mink, pigs, rabbits, pangolins, and other animals from which they could jump into human populations with little to no immunity, as most researchers suspect SARS-CoV-2 did. “Chances are, in the next 10 to 50 years, we may have another outbreak like SARS-CoV-2,” says structural biologist Andrew Ward of Scripps Research, one of the scientists who submitted the 2017 proposal NIAID rejected. The agency has not given out any of its new awards yet, but Ward’s lab is already pursuing a vaccine targeting a subset of beta coronaviruses. Some two dozen other research groups around the world have similar pancoronavirus vaccine projects underway. Their approaches include novel nanocages arrayed with viral particles, the cutting-edge messenger RNA (mRNA) technique at the heart of proven COVID-19 vaccines, and cocktails of inactivated viruses, the mainstay of past vaccines. A few teams have even published promising results from animal tests of early candidates. No pancoronavirus vaccine has entered human trials, and how to evaluate a candidate’s protection against diseases that have not yet emerged remains a challenge. Nor is it clear how such a vaccine might be used. One possibility: keeping it in reserve until a new human threat emerges. “We might be able to prime everybody to get a basic level of immunity” against the emerging virus, buying time to make a more specific vaccine, Ward says. Despite the many unknowns, the rapid success of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 has sparked optimism. This coronavirus doesn’t seem particularly difficult to foil with a vaccine, which raises hopes that the immune system can be trained to outwit its relatives, too. Survivors of SARS years ago provide more encouragement: Some of their antibodies—an immune memory of that viral encounter—can also stymie the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 in lab dishes. NIAID’s Barney Graham, who helped develop Moderna’s mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, shares the optimism about pancoronavirus vaccines. “Compared to flu and HIV, this is going to be relatively easy to accomplish,” he predicts. EARLIER THIS YEAR, Hannah Turner, a technician at Scripps Research who works with Ward, took a cold, hard look at a now infamous protein: SARS-CoV-2’s spike, which enables the virus to infect cells and is at the heart of several successful COVID-19 vaccines. All coronaviruses have these spikes, which create the distinctive crownlike appearance that earned them their name, and most pancoronavirus vaccine efforts aim to rouse an immune response to some part of the spike protein. On this February morning, Turner mixes labmade copies of the SARS-CoV-2 spike with “broadly neutralizing” antibodies harvested from COVID-19 patients. These antibodies powerfully prevent multiple variants of SARS-CoV-2, as well as the original SARS virus, SARS-CoV, from infecting susceptible cells in test tube studies. Turner then freezes the spike-antibody mixtures with liquid nitrogen and places the resulting crystals in a $4 million microscope the size of three refrigerators. It begins bombarding the samples with up to 200 kilovolts of electrons to map the spike-antibody complexes at atomic resolution—an increasingly popular technique called cryo–electron microscopy (cryo-EM). What resembles a telescope view of lunar landscapes unfolds across four monitors. Turner’s trained eye spots the crystallized spike proteins, clumped together in groups of three called trimers and studded with antibodies. She points out one of the fanlike structures. “It’s pretty cool,” she says. “This is what you want to see.” The computers over the next few days will sort through 1100 different angles of her sample, migrating the best views into software that creates a gorgeous “final map” of spike with an attached antibody, at a resolution that approaches 3 angstroms, just a tad thicker than a strand of DNA. By creating similar portraits of spikes from many different coronaviruses with broadly neutralizing antibodies bound to them, Ward hopes to identify short segments of the protein—so-called epitopes—key to that binding for all the pathogens. Those epitopes, Ward believes, are the key to designing a vaccine that can trigger a broad immune attack on coronaviruses.... Published in Science (April 15, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abi9939

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...