Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

February 22, 10:13 AM

|

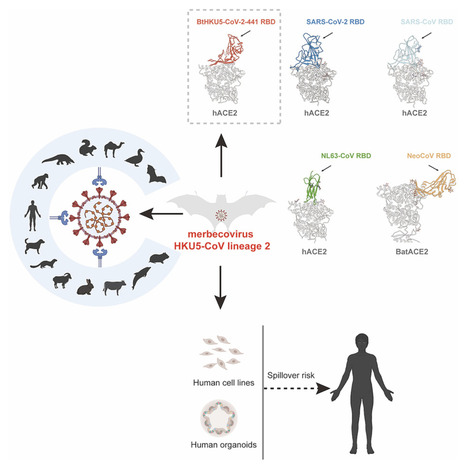

Highlights • A distinct HKU5 coronavirus lineage (HKU5-CoV-2) is discovered in bats • Bat HKU5-CoV-2 uses human ACE2 receptor and ACE2 orthologs from multiple species • Bat HKU5-CoV-2 RBD engages human ACE2 with a distinct binding mode from other CoVs • Bat HKU5-CoV-2 was isolated and infect human-ACE2-expressing cells Summary Merbecoviruses comprise four viral species with remarkable genetic diversity: MERS-related coronavirus, Tylonycterisbat coronavirus HKU4, Pipistrellusbat coronavirus HKU5, and Hedgehog coronavirus 1. However, the potential human spillover risk of animal merbecoviruses remains to be investigated. Here, we reported the discovery of HKU5-CoV lineage 2 (HKU5-CoV-2) in bats that efficiently utilize human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a functional receptor and exhibits a broad host tropism. Cryo-EM analysis of HKU5-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain (RBD) and human ACE2 complex revealed an entirely distinct binding mode compared with other ACE2-utilizing merbecoviruses with RBD footprint largely shared with ACE2-using sarbecoviruses and NL63. Structural and functional analyses indicate that HKU5-CoV-2 has a better adaptation to human ACE2 than lineage 1 HKU5-CoV. Authentic HKU5-CoV-2 infected human ACE2-expressing cell lines and human respiratory and enteric organoids. This study reveals a distinct lineage of HKU5-CoVs in bats that efficiently use human ACE2 and underscores their potential zoonotic risk. Published in Cell (Feb. 18, 2025)

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 10, 2024 1:30 PM

|

The angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor is shared by various coronaviruses with distinct receptor-binding domain (RBD) architectures, yet our understanding of these convergent acquisition events remains elusive. Here, we report that two European bat MERS-related coronaviruses (MERSr-CoVs) infecting Pipistrellus nathusii (P.nat), MOW15-22 and PnNL2018B, use ACE2 as their receptor, with narrow ortholog specificity. Cryo-electron microscopy structures of the MOW15-22 RBD-ACE2 complex unveil an unexpected and entirely distinct binding mode, mapping 50Å away from that of any other known ACE2-using coronaviruses. Functional profiling of ACE2 orthologs from 105 mammalian species led to the identification of host tropism determinants, including an ACE2 N432-glycosylation restricting viral recognition, and the design of a soluble P.nat ACE2 mutant with potent viral neutralizing activity. Our findings reveal convergent acquisition of ACE2 usage for merbecoviruses found in European bats, underscoring the extraordinary diversity of ACE2 recognition modes among coronaviruses and the promiscuity of this receptor. Preprint in bioRxiv (July 8, 2024): https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.02.560486

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 29, 2023 11:54 AM

|

Horseshoe bats carry viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2, but they probably can’t spread in people yet. Coronavirus hunters looking for the next pandemic threats have focused on China and southeast Asia, where wild bats carry SARS-CoV-2’s closest known relatives. But a survey of UK bat species suggests that researchers might want to cast a wider net. The trawl turned up new coronaviruses, and some from the same group as SARS-CoV-2. Laboratory studies with safe versions of these viruses suggest that some share key adaptations with SARS-CoV-2 — but are unlikely to spread in humans without further evolution. SARS-CoV-2 belongs to a group of coronaviruses called sarbecoviruses, which circulate in bats. But before the pandemic, efforts to find and characterize these viruses focused on Asia. “Europe and the UK had been totally overlooked,” says Vincent Savolainen, an evolutionary geneticist at Imperial College London who led the study, published on 27 June in Nature Communications. To help plug this gap, Savolainen and his colleagues teamed up with groups involved in bat rehabilitation and conservation to collect a total of 48 faecal samples from bats representing 16 of the 17 species that breed in the United Kingdom. Genetic sequencing turned up nine coronaviruses, including four sarbecoviruses and one related to the coronavirus responsible for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, or MERS, which periodically spills over into camels and humans. Ties that bind — or not To gauge the threat posed by the UK coronaviruses, the researchers created pseudoviruses: non-replicating forms of HIV that are engineered to carry the spike protein that coronaviruses use to infect cells. One sarbecovirus found in a lesser horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus hipposideros) had a spike protein that was able to infect human cells by attaching to a protein called ACE2, the same receptor used by SARS-CoV-2. But the UK sarbecovirus’s version of spike didn’t attach nearly as strongly as SARS-CoV-2’s, and pseudoviruses could infect only human cells with unnaturally high levels of ACE2. This makes it unlikely that the virus could readily infect people and spread, the researchers say. That’s reassuring, but other sarbecoviruses circulating in British bats could be able to bind to human ACE2 more efficiently, says Michael Letko, a molecular virologist at Washington State University in Pullman, who was not involved in the study. A February preprint surveyed UK lesser horseshoe bats and found signs that around half were infected with sarbecoviruses. Further adaptations that help these viruses to infect human cells more efficiently might not be hard to come by, Letko says. “Once the virus has its foot in the door, it’s easier to adapt further.” Tyler Starr, a molecular evolutionary biologist at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, says that sarbecoviruses identified so far in Europe and in Africa probably represent the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the group’s true diversity and geographical distribution. He wouldn’t be surprised if the next sarbecovirus to spill over into humans came from an unprecedented location or branch of the family tree. “The next pandemic threat could very well be in our own backyard,” adds Letko. Cited research published in Nat. Communications (June 27, 2023): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38717-w

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

March 13, 2022 1:44 PM

|

A core question in understanding the drivers of zoonotic emergence is whether particular animal groups are common sources of zoonotic viruses. If so, can this information be used to establish a watch-and-act list of those species most likely to carry potentially pandemic viruses? It has long been known that most viral infections in humans have their ancestry in mammals (4). Birds are the only other probable source of zoonotic diseases, with the various forms of avian influenza virus that occasionally appear in humans (such as H5 subtype viruses) presenting an ongoing pandemic threat. Although viruses are often abundant in other animal groups (such as bony fish), their phylogenetic distance to humans greatly reduces the likelihood of successful cross-species transmission. Within the mammals, a variety of groups have served as reservoirs for zoonotic viruses (3), particularly those with which humans share proximity, either as food sources (such as pigs) or because they have adapted to human lifestyles (like some species of rodent), as well as those that are so closely related to humans (such as nonhuman primates) that viruses face little adaptive challenge when establishing human-to-human transmission. Most of all, since the emergence of SARS in late 2002, there has been intense interest in bats as virus reservoirs, although this may in part reflect biases in both ascertainment and confirmation (5). Although bats seemingly tolerate a high diversity and abundance of viruses, the underlying immunological, physiological, and ecological reasons for this are not fully understood (6). More pragmatically, the majority of bat viruses have not appeared in humans, and those that have emerged often do so through other host species (i.e., “intermediate hosts”) prior to successful emergence (7). Bats are important players in disease emergence, but they are only one component of the more complex global viral ecosystem. A related question is whether the viruses that are most likely to emerge in humans can be identified. Although metagenomic sequencing is revealing an increasingly large virosphere, with mammals carrying many thousands of different viruses, most of which remain undocumented (5), the greatest pandemic risk is posed by respiratory viruses because their fluid mode of (sometimes asymptomatic) transmission makes their control especially challenging. Three groups of RNA viruses that regularly jump species boundaries best fit this risk profile: paramyxoviruses, influenza viruses, and, particularly, coronaviruses. Hendra and Nipah viruses, both with ultimate bat ancestry, are exemplars of paramyxoviruses that have emerged in humans. Although neither have resulted in large-scale outbreaks, it is possible that more transmissible paramyxoviruses (such as the case of measles virus) lurk in the mammalian virosphere. The documented host range of influenza viruses is growing, including recent reports of avian H9N2 influenza virus in diseased Asian badgers (2), but most human influenza virus pandemics have their roots in those viruses that circulate in waterbirds and poultry, often with the secondary involvement of pigs. Fortunately, birds and humans are sufficiently different in most virus–cell interactions that avian viruses are usually unable to successfully transmit among humans......

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 27, 2021 1:19 PM

|

Souilmi et al. find that strong genetic adaptation occurred in human East Asian populations, at multiple genes that interact with coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2. The adaptation

started 25,000 years ago, and functional analysis of the adapting genes supports the occurrence of a corona- or related virus epidemic around that time in East Asia. Highlights - Ancient viral epidemics can be identified through adaptation in host genomes

- Genomes in East Asia bear the signature of an ∼25,000-year-old viral epidemic

- Functional analysis supports an ancient corona- or related virus epidemic

Summary The current severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has emphasized the vulnerability of human populations to novel viral pressures, despite the vast array of epidemiological and biomedical tools now available. Notably, modern human genomes contain evolutionary information tracing back tens of thousands of years, which may help identify the viruses that have impacted our ancestors—pointing to which viruses have future pandemic potential. Here, we apply evolutionary analyses to human genomic datasets to recover selection events involving tens of human genes that interact with coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, that likely started more than 20,000 years ago. These adaptive events were limited to the population ancestral to East Asian populations. Multiple lines of functional evidence support an ancient viral selective pressure, and East Asia is the geographical origin of several modern coronavirus epidemics. An arms race with an ancient coronavirus, or with a different virus that happened to use similar interactions as coronaviruses with human hosts, may thus have taken place in ancestral East Asian populations. By learning more about our ancient viral foes, our study highlights the promise of evolutionary information to better predict the pandemics of the future. Importantly, adaptation to ancient viral epidemics in specific human populations does not necessarily imply any difference in genetic susceptibility between different human populations, and the current evidence points toward an overwhelming impact of socioeconomic factors in the case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Published in Current Biology (June 24, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.05.067

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

May 16, 2021 1:22 PM

|

Researchers at the University of Duke found mRNA-based vaccines, such as Pfizer and Moderna, induce antibodies that may help fight against coronavirus variants. The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are not only effective against COVID-19, but may also help prevent future pandemics. Researchers at Duke University came to this concluding after testing mRNA-based vaccines similar to the jabs used on lab monkeys. According to their findings, which were published in Nature this week, these variety of vaccines induced “broadly neutralizing” antibodies that appeared to protect against Sars-CoV-2—the infection that causes COVID-19—as well as potential variants of coronavirus that could jump from animal to human. The findings may offer the public a sense of relief as many experts and epidemiologists say there’s a strong chance another pandemic will occur. In an effort to help prevent another outbreak, the team of Duke University researchers developed a pan-coronavirus vaccine that is protein-based rather than mRNA-based. The vaccine was tested on lab animals and showed promising results in fighting the original COVID-19 strain and other variants. Researchers said the vaccine also appeared to stop the virus from replicating in the lungs and nose, which could drastically reduce rates of transmission. “We began this work last spring with the understanding that, like all viruses, mutations would occur in the SARS-CoV-2 virus,” the study’s senior author Barton F. Haynes, director of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute, said in a press release. “The mRNA vaccines were already under development, so we were looking for ways to sustain their efficacy once those variants appeared. This approach not only provided protection against SARS-CoV-2, but the antibodies induced by the vaccine also neutralized variants of concern that originated in the United Kingdom, South Africa and Brazil. And the induced antibodies reacted with quite a large panel of coronaviruses.” Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s leading expert in infectious diseases, expressed optimism about Duke’s pan-coronavirus vaccine during a Thursday press conference, saying the next step was to get approval for human trials. “We always have to have a caveat when you’re dealing in a nonhuman primate,” he said, “nonetheless, this is an extremely important proof of concept that we will be aggressively pursuing as we get into the development of human trials,” Fauci said. Cited study published in Nature (May 10, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03594-0

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

November 8, 2020 2:14 PM

|

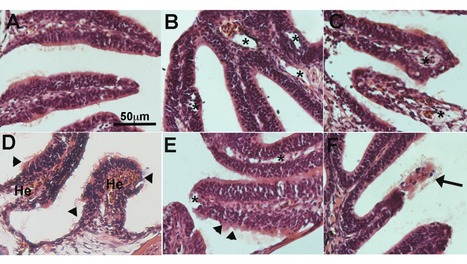

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted the search for animal models that recapitulate the pathophysiology observed in humans infected with SARS-CoV-2 and allow rapid and high throughput testing of drugs and vaccines. Exposure of larvae to SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) receptor binding domain (RBD) recombinant protein was sufficient to elevate larval heart rate and treatment with captopril, an ACE inhibitor, reverted this effect. Intranasal administration of SARS-CoV-2 S RBD in adult zebrafish recombinant protein caused severe olfactory and mild renal histopathology. Zebrafish intranasally treated with SARS-CoV-2 S RBD became hyposmic within minutes and completely anosmic by 1 day to a broad-spectrum of odorants including bile acids and food. Single cell RNA-Seq of the adult zebrafish olfactory organ indicated widespread loss of expression of olfactory receptors as well as inflammatory responses in sustentacular, endothelial, and myeloid cell clusters. Exposure of wildtype zebrafish larvae to SARS-CoV-2 in water did not support active viral replication but caused a sustained inhibition of ace2 expression, triggered type 1 cytokine responses and inhibited type 2 cytokine responses. Combined, our results establish adult and larval zebrafish as useful models to investigate pathophysiological effects of SARS-CoV-2 and perform pre-clinical drug testing and validation in an inexpensive, high throughput vertebrate model. Preprint available in bioRxiv (Nov. 8 , 2020): https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.06.368191

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

October 9, 2020 12:35 PM

|

The new coronavirus tears through areas where residents generally keep to their own small, close-knit communities. But the virus takes its time spreading in crowded cities where residents of different neighbourhoods tend to intermingle, ultimately infecting more people than in the relatively isolated areas. Moritz Kraemer at the University of Oxford, UK, and his colleagues modelled the spread of SARS-CoV-2 through communities of various sizes and population densities(B. Rader et al. Nature Med. https://doi.org/fcjk; 2020). The researchers validated their model by comparing its output with known data on individual movements and infection rates in crowded Chinese cities such as Wuhan and less densely packed provinces in Italy. The team’s model predicts relatively short, intense spikes in COVID-19 cases in relatively uncrowded cities where residents stick to their own neighbourhoods rather than mingling freely. In crowded cities, however, people are more likely to have to cope with outbreaks that last longer than do those in the countryside. The researchers applied their model to 310 cities worldwide, and predict that those with relatively even population distributions, such as Ulaanbaatar in Mongolia, could expect a short-term explosion in cases. But more densely settled urban centres, such as Madrid, can expect more protracted outbreaks. Published in Nature Medicine (October 5, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1104-0

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

August 20, 2020 11:27 AM

|

Now, a new study published in the preprint server bioRxiv in August 2020 shows that under conditions resembling those in vivo, IFNs may promote efficient viral invasion instead. The virus behind the current COVID-19 pandemic, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is known to spread more efficiently than the earlier pathogenic coronaviruses, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV. However, the case fatality rate so far has been much lower, at 2% to 5%, compared to 10% in SARS and ~ 40% in MERS. Scientists think the virus is inhibited by interferons (IFNs), even more than the earlier viruses. In fact, IFNs are currently being used to reduce the severity of COVID-19. Now, a new study published in the preprint server bioRxiv* in August 2020 shows that under conditions resembling those in vivo, IFNs may promote efficient viral invasion instead. What are IFITMs? Interferon-induced transmembrane proteins (IFITMs 1, 2, and 3) are proteins that are considered to be inhibitory of a variety of viruses, including the SARS-CoVs. Most of the evidence for this has come from studies that used cells that overexpress these proteins and are infected by pseudoviruses. The investigators looked at innate immune effectors directed against SARS-CoV-2 entry into the target cells. Viral entry involves spike-mediated recognition of the host receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) 2, triggering an irreversible conformational change of the spike protein to its fusion form by proteolytic cleavage into S1 and S2 subunits. The cleaved protein fuses to the plasma membrane and gains entry to the cell. IFITMs are a family of IFN stimulated genes (ISGs) is known to prevent this fusion, in the case of influenza A viruses, rhabdoviruses, and HIV. IFITM Overexpression Inhibits Pseudovirus S Binding Previous work has shown that when these proteins are expressed at excessively high levels, pseudoparticles expressing the spike protein of SARS and MERS are unable to enter the host cell. The mechanism of inhibition might reduce the rigidity and curvature of the plasma membrane such that fusion cannot happen. While IFITM1 is only the plasma membrane, IFITM2 and 3 are localized on lysosomal membranes within the cell. Many scientists think that such viruses cannot replicate in cells where these proteins are expressed. However, some studies have shown that IFITMs can actually increase the intensity of infection with some human coronaviruses. At the same time, mutant IFITMs could enhance infection with many viruses from this family, including SARS. The current study shows that the overexpression of IFITMs specifically reduces the entry of SARS-CoV-2 spike-mediated pseudoparticles, by two orders of magnitude for IFITM2 and IFITM3 in particular, and less potently by IFITM1. Infectivity of these pseudoviruses was not reduced, however, and in fact, it was slightly increased in one case, since it may increase the rate at which the spike protein is built into the pseudovirus. The initial tests showed that both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins expressed in pseudoviruses are inhibited efficiently by IFITMs, the first even more than the second. The mechanism of such inhibition appears to be via ubiquitination and palmitoylation. In all cases, they found that IFITMs reduce cell-to-cell fusion mediated by the spike-ACE2 binding. The depletion of these proteins led to a 3- to 7-fold increase in spike-mediated infection by all pseudoviral particles. Further testing in a cell line lacking IFITM expression showed that the number of S-ACE2 binding foci leaped upward by four- to ten-fold. These findings strongly imply that IFITM proteins are efficient inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 S-mediated viral entry.... Study available as preprint at bioRxiv (August 18, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.18.255935

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

August 4, 2020 11:37 AM

|

Yunjeong Kim and Kyeong-Ok "KC" Chang, virologists in the College of Veterinary Medicine at Kansas State University, have published a study showing a possible therapeutic treatment for COVID-19. Pathogenic coronaviruses are a major threat to global public health, as shown by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, or SARS-CoV; Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, known as MERS-CoV; and the newly emerged SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 infection. The study, "3C-like protease inhibitors block coronavirus replication in vitro and improve survival in MERS-CoV-infected mice," appears in the Aug. 3 issue of the prestigious medical journal Science Translational Medicine. It reveals how small molecule protease inhibitors show potency against human coronaviruses. These coronavirus 3C-like proteases, known as 3CLpro, are strong therapeutic targets because they play vital roles in coronavirus replication. Vaccine developments and treatments are the biggest targets in COVID-19 research, and treatment is really key," said Chang, professor of diagnostic medicine and pathobiology. "This paper describes protease inhibitors targeting coronavirus 3CLpro, which is a well-known therapeutic target." The study demonstrates that this series of optimized coronavirus 3CLpro inhibitors blocked replication of the human coronaviruses MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 in cultured cells and in a mouse model for MERS. These findings suggest that this series of compounds should be investigated further as a potential therapeutic for human coronavirus infection. Chang and Kim have been using National Institutes of Health grants to develop antiviral drugs to treat MERS and human norovirus infections. Their work extends to other human viruses such as rhinoviruses and SARS-CoV-2... Original study published in Science Translational Medicine (Aug. 3, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abc5332

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 16, 2020 11:09 AM

|

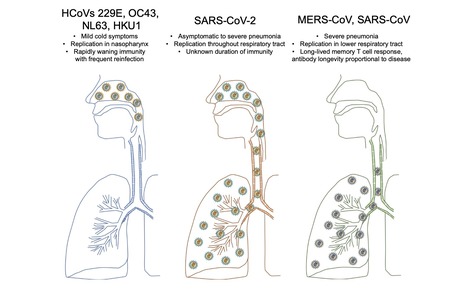

A key goal to controlling COVID-19 is developing an effective vaccine. Development of a vaccine requires knowledge of what constitutes a protective immune response and also features that might be pathogenic. Protective and pathogenic aspects of the response to SARS-CoV-2 are not well understood, partly because the virus has infected humans for only 6 months. However, insight into coronavirus immunity can be informed by previous studies of immune responses to non-human coronaviruses, to common cold coronaviruses, and to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Here we review the literature describing these responses and discuss their relevance to the SARS-CoV-2 immune response. Original review available at Immunity (July 14, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2020.07.005

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 15, 2020 11:02 AM

|

Many mass immunization efforts worldwide were halted this spring to prevent spread of the virus at crowded inoculation sites. The consequences have been alarming. As poor countries around the world struggle to beat back the coronavirus, they are unintentionally contributing to fresh explosions of illness and death from other diseases — ones that are readily prevented by vaccines. This spring, after the World Health Organization and UNICEF warned that the pandemic could spread swiftly when children gathered for shots, many countries suspended their inoculation programs. Even in countries that tried to keep them going, cargo flights with vaccine supplies were halted by the pandemic and health workers diverted to fight it. Now, diphtheria is appearing in Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal. Cholera is in South Sudan, Cameroon, Mozambique, Yemen and Bangladesh. A mutated strain of poliovirus has been reported in more than 30 countries. And measles is flaring around the globe, including in Bangladesh, Brazil, Cambodia, Central African Republic, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Nepal, Nigeria and Uzbekistan. Of 29 countries that have currently suspended measles campaigns because of the pandemic, 18 are reporting outbreaks. An additional 13 countries are considering postponement. According to the Measles and Rubella Initiative, 178 million people are at risk of missing measles shots in 2020. The risk now is “an epidemic in a few months’ time that will kill more children than Covid,” said Chibuzo Okonta, the president of Doctors Without Borders in West and Central Africa. As the pandemic lingers, the W.H.O. and other international public health groups are now urging countries to carefully resume vaccination while contending with the coronavirus. At stake is the future of a hard-fought, 20-year collaboration that has prevented 35 million deaths in 98 countries from vaccine-preventable diseases, and reduced mortality from them in children by 44 percent, according to a 2019 study by the Vaccine Impact Modeling Consortium, a group of public health scholars...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 7, 2020 12:45 AM

|

Pandemic hunting scientists warn of a 'perfect storm' for new diseases to emerge from wildlife. In the last 20 years, we've had six significant threats - SARS, MERS, Ebola, avian influenza and swine flu," Prof Matthew Baylis from the University of Liverpool told BBC News. "We dodged five bullets but the sixth got us. "And this is not the last pandemic we are going to face, so we need to be looking more closely at wildlife disease." As part of this close examination, he and his colleagues have designed a predictive pattern-recognition system that can probe a vast database of every known wildlife disease. Across the thousands of bacteria, parasites and viruses known to science, this system identifies clues buried in the number and type of species they infect. It uses those clues to highlight which ones pose most of a threat to humans. If a pathogen is flagged as a priority, scientists say they could direct research efforts into finding preventions or treatments before any outbreak happens. "It will be another step altogether to find out which diseases could cause a pandemic, but we're making progress with this first step," Prof Baylis said. Many scientists agree that our behaviour - particularly deforestation and our encroachment on diverse wildlife habitats - is helping diseases to spread from animals into humans more frequently. According to Prof Kate Jones from University College London, evidence "broadly suggests that human-transformed ecosystems with lower biodiversity, such as agricultural or plantation landscapes, are often associated with increased human risk of many infections". "That's not necessarily the case for all diseases," she added. "But the kinds of wildlife species that are most tolerant of human disturbance, such as certain rodent species, often appear to be more effective at hosting and transmitting pathogens....

|

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

January 9, 12:29 PM

|

The zoonotic transmission of bat coronaviruses poses a threat to human health. However, the diversity of bat-borne coronaviruses remains poorly characterized in many geographical areas. Here, we recovered six complete coronavirus genomes by performing a metagenomic analysis of fecal samples from hundreds of individual bats captured in Spain, a country with high bat species diversity. Three of these genomes corresponded to potentially novel coronavirus species belonging to the alphacoronavirus genus. Phylogenetic analyses revealed that some of these viruses are closely related to coronaviruses previously described in bats from other countries, suggesting the existence of a shared viral reservoir worldwide. Using viral pseudotypes, we investigated the receptor usage of the identified viruses and found that one of them can use human and bat ACE2, highlighting its zoonotic potential. However, the receptor usage of the other viruses remains unknown. This study broadens our understanding of coronavirus diversity and identifies research priorities for the prevention of zoonotic viral outbreaks. Preprint in biorXiv (Jan. 8, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.01.07.631674

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

August 9, 2023 12:56 PM

|

The Orthocoronaviridae subfamily is large comprising four highly divergent genera. Four seasonal coronaviruses were circulating in humans prior to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Infection with these viruses induced antibody responses that are relatively narrow with little cross-reactivity to spike proteins of other coronaviruses. Here, we report that infection with and vaccination against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) induces broadly crossreactive binding antibodies to spikes from a wide range of coronaviruses including members of the sarbecovirus subgenus, betacoronaviruses including Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS CoV), and extending to alpha-, gamma- and delta-coronavirus spikes. These data show that the coronavirus spike antibody landscape in humans has profoundly been changed and broadened as a result of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. While we do not understand the functionality of these crossreactive antibodies, they may lead to enhanced resistance of the population to infection with newly emerging coronaviruses with pandemic potential. Preprunt in medRxiv (August 6, 2023): https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.01.23293522

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

January 8, 2023 6:44 PM

|

Parts of Southeast Asia where human and bat population densities are highest could be infection hotspots, a study finds. Tens of thousands of people in Southeast Asia could be infected with coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV-2 each year, a study published yesterday (August 9) in Nature Communications estimates. The research, which first appeared as a preprint last September, analyzed the geographic ranges of 26 bat species and found their habitat overlapped regions where half a billion people live, representing an area larger than 5 million square kilometers, reports Reuters. Analyzing that data along with estimates of the number of people who exhibited detectable coronavirus antibodies predicted that approximately 66,000 potential infections occur each year. Stephanie Seifert, a virus ecologist at Washington State University in Pullman who was not involved in the research, tells Nature that the work “highlights how often these viruses have the opportunity to spillover.” The study coauthors considered the geographic ranges of bats known to host SARS-related viruses—primarily horseshoe bats (family Rhinolophidae) and Old World leaf-nosed bats (family Hipposideridae). They found hot spots of potential spillover events in southern China, parts of Myanmar, and the Indonesian island of Java—where both bat and human populations are particularly dense, reports Nature. Most of these SARS-related viruses don’t easily spread among humans or cause illness. But study coauthor Peter Daszak tells Nature that with enough infections “raining down on people, you will eventually get a pandemic.” However, Alice Hughes, a conservation biologist at the University of Hong Kong who was not involved in the work, tells Nature that this analysis relies on outdated and low-resolution geographical range data. “What they are trying to do is very valuable and needs to be done, but it has to be done with more finesse,” she says. The study authors argue their research can focus spillover monitoring to high-risk regions in order to identify outbreaks sooner. Renata Muylaert, a disease ecologist at Massey University in New Zealand who was not involved in the research, agrees, telling Nature, “The article has considerable significance for surveillance.” This analysis looked only at bat-to-human spillover events and did not consider infections that first transmit from bats to an intermediate animal and later to humans. Daszak tells Nature that there were limited data on that type of event, but that including them would have “massively increased the estimated risk of spillovers.”

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 27, 2021 1:43 PM

|

A few dozen human genes rapidly evolved in ancient East Asia to thwart coronavirus infections, scientists say. Those genes could be crucial to today’s pandemic. Researchers have found evidence that a coronavirus epidemic swept East Asia some 20,000 years ago and was devastating enough to leave an evolutionary imprint on the DNA of people alive today. The new study suggests that an ancient coronavirus plagued the region for many years, researchers say. The finding could have dire implications for the Covid-19 pandemic if it’s not brought under control soon through vaccination. “It should make us worry,” said David Enard, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Arizona who led the study, which was published on Thursday in the journal Current Biology. “What is going on right now might be going on for generations and generations.” Until now, researchers could not look back very far into the history of this family of pathogens. Over the past 20 years, three coronaviruses have adapted to infect humans and cause severe respiratory disease: Covid-19, SARS and MERS. Studies on each of these coronaviruses indicate that they jumped into our species from bats or other mammals. Four other coronaviruses can also infect people, but they usually cause only mild colds. Scientists did not directly observe these coronaviruses becoming human pathogens, so they have relied on indirect clues to estimate when the jumps happened. Coronaviruses gain new mutations at a roughly regular rate, and so comparing their genetic variation makes it possible to determine when they diverged from a common ancestor. The most recent of these mild coronaviruses, called HCoV-HKU1, crossed the species barrier in the 1950s. The oldest, called HCoV-NL63, may date back as far as 820 years. But before that point, the coronavirus trail went cold — until Dr. Enard and his colleagues applied a new method to the search. Instead of looking at the genes of the coronaviruses, the researchers looked at the effects on the DNA of their human hosts. Over generations, viruses drive enormous amounts of change in the human genome. A mutation that protects against a viral infection may well mean the difference between life and death, and it will be passed down to offspring. A lifesaving mutation, for example, might allow people to chop apart a virus’s proteins. But viruses can evolve, too. Their proteins can change shape to overcome a host’s defenses. And those changes might spur the host to evolve even more counteroffensives, leading to more mutations. When a random new mutation happens to provide resistance to a virus, it can swiftly become more common from one generation to the next. And other versions of that gene, in turn, become rarer. So if one version of a gene dominates all others in large groups of people, scientists know that is most likely a signature of rapid evolution in the past. In recent years, Dr. Enard and his colleagues have searched the human genome for these patterns of genetic variation in order to reconstruct the history of an array of viruses. When the pandemic struck, he wondered whether ancient coronaviruses had left a distinctive mark of their own. He and his colleagues compared the DNA of thousands of people across 26 different populations around the world, looking at a combination of genes known to be crucial for coronaviruses but not other kinds of pathogens. In East Asian populations, the scientists found that 42 of these genes had a dominant version. That was a strong signal that people in East Asia had adapted to an ancient coronavirus. But whatever happened in East Asia seemed to have been limited to that region. “When we compared them to populations around the world, we couldn’t find the signal,” said Yassine Souilmi, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Adelaide in Australia and a co-author of the new study. The scientists then tried to estimate how long ago East Asians had adapted to a coronavirus. They took advantage of the fact that once a dominant version of a gene starts being passed down through the generations, it can gain harmless random mutations. As more time passes, more of those mutations accumulate. Dr. Enard and his colleagues found that the 42 genes all had about the same number of mutations. That meant that they had all rapidly evolved at about the same time. “This is a signal we should absolutely not expect by chance,” Dr. Enard said. They estimated that all of those genes evolved their antiviral mutations sometime between 20,000 and 25,000 years ago, most likely over the course of a few centuries. It’s a surprising finding, since East Asians at the time were not living in dense communities but instead formed small bands of hunter-gatherers. Aida Andres, an evolutionary geneticist at the University College London who was not involved in the new study, said she found the work compelling. “I’m quite convinced there’s something there,” she said. Still, she didn’t think it was possible yet to make a firm estimate of how long ago the ancient epidemic took place. “The timing is a complicated thing,” she said. “Whether that happened a few thousand years before or after — I personally think it’s something that we cannot be as confident of.” Scientists looking for drugs to fight the new coronavirus might want to scrutinize the 42 genes that evolved in response to the ancient epidemic, Dr. Souilmi said. “It’s actually pointing us to molecular knobs to adjust the immune response to the virus,” he said. Dr. Anders agreed, saying that the genes identified in the new study should get special attention as targets for drugs. “You know that they’re important,” she said. “That’s the nice thing about evolution.”

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

May 21, 2021 11:32 AM

|

Research increases worry about the pandemic potential of other members of the virus family. Eight children hospitalized with pneumonia in Malaysia several years ago had evidence of infections with a novel coronavirus similar to one found in dogs, a research team reports today. Only seven coronaviruses were previously known to infect people, the latest being SARS-CoV-2, the spark of the COVID-19 pandemic. The discovery of this likely new human pathogen, along with the report of an instance of a coronavirus that appears to have jumped from pigs to people many years ago, could significantly expand which members of the viral family pose another global threat. “I think the more we look, the more we will find that these coronaviruses are crossing species everywhere,” says Stanley Perlman, a virologist at the University of Iowa who was not involved in the new work. The researchers have not definitely linked either new virus to human disease. And there’s no evidence that the two new coronaviruses can transmit between people—each infection may have been a dead-end jump into a person from a nonhuman host. But many researchers worry the viruses may evolve that ability within a person or the animals they normally infect. A complete genome sequence of the virus found in one Malaysian patient, reported today in Clinical Infectious Diseases, reveals a chimera of genes from four coronaviruses: two previously identified canine coronaviruses, one known to infect cats, and what looks like a pig virus. This is the first report suggesting a caninelike coronavirus can replicate in people, and further studies will need to confirm the ability. The researchers have grown the virus in dog tumor cells but not yet in human cells. Unlike with SARS-CoV-2 and other known human coronaviruses, “We don’t have any clear evidence that this particular [coronavirus] strain is better adapted to humans because of its spike structure,” says veterinary virologist Anastasia Vlasova of Ohio State University (OSU), Wooster, lead author of the study. Human infections from dog coronaviruses may occur “at a much higher frequency than we previously thought,” she adds. This particular virus might not transmit between people, but we don’t know that for sure, Vlasova cautions. The eight children whose tissue samples Vlasova and her colleagues studied were mainly living in traditional longhouses or villages in rural or suburban Sarawak on Borneo, where they likely had frequent exposure to domestic animals and jungle wildlife. They were among 301 hospitalized pneumonia patients during 2017–18 and the researchers screened their nasopharyngeal samples—tissue from the upper part of the throat—for a large variety of human and nonhuman coronaviruses. Standard hospital diagnostics for pneumonia or other respiratory illness would not have detected dog and cat coronaviruses. No one has been looking for these viruses in patients with such illnesses until recently. “These canine and feline coronaviruses are everywhere in the world,” Perlman says. The entire novel virus sequence from the children’s samples most resembles a canine coronavirus. However, the sequence for its spike protein, which attaches to host cell receptors to initiate an infection, is closely related to the spike sequence of canine coronavirus type I and the one for a porcine coronavirus known as transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV). And one part of the spike protein bears a 97% similarity to the spike of a feline coronavirus. This chimera is unlikely to have arisen at once, but instead involved repeat genetic reshuffles between different coronaviruses over time. “This is a mosaic of several different recombinations, happening over and over, when nobody’s watching. And then boom, you get this monstrosity,” says virologist Benjamin Neuman at Texas A&M University, College Station. The animal that actually transmitted the novel virus to the people could have been a cat, pig, dog, “or some wild carnivores,” says Vito Martella, a veterinary virologist at the University of Bari in Italy. He plans to screen stored fecal samples from Italian children with acute gastroenteritis to see whether he can find something similar. Researchers already knew three canine coronavirus subtypes mix readily with feline and porcine coronaviruses. “What is more surprising is that these [animal] viruses can actually cause disease in a person,” Perlman says, because one would expect them to lack some of the genes important for adapting well to people. Seven of the eight children whose tissues harbored sequences of the virus were younger than 5 years old, and four of them were infants, mostly from Indigenous ethnic groups. Each was hospitalized for 4 to 7 days and recovered. Scientists divide coronaviruses into four genera—alpha, beta, gamma, and delta—and the new one is an alpha. It is the third such alpha coronavirus to infect people; the other two cause common colds, and most people are exposed to them early in life. That pattern may explain why only children were perhaps sickened by this new one. Ralph Baric, a virologist at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, suggests adults may have some immunity to the newly discovered alpha coronavirus because of repeated exposure to the other two. So far, the most dangerous human coronaviruses—SARS-CoV-1, SARS-CoV-2, and MERS-CoV—are the betas. Researchers haven’t seen alphas trigger an outbreak of serious disease in humans, Neuman says, “but that doesn’t feel like much comfort in the wild world of viruses.” In March, researchers at the University of Florida reported in a medRxiv preprint the first evidence of a porcine delta coronavirus that infects people, in serum from three Haitian children who had fevers in 2014—15. The researchers transferred serum samples into monkey cells and were able to grow viruses that they matched, genetically, to known porcine coronaviruses (The work has been submitted to a peer-reviewed journal.) Delta coronaviruses were once thought to infect only birds. Then, in 2012, a delta coronavirus infected swine in Hong Kong. It “appears to have jumped over from songbirds,” says OSU coronavirologist Linda Saif, who went on to isolate the virus in swine cell cultures. The same virus caused a major fatal diarrheal disease outbreak in baby pigs in the United States in 2014. It has since been shown to infect cell lines from humans, pigs, and chickens; lab studies have shown the virus causes persistent infection and diarrheal disease when put into poultry. “It’s out on its own, a left field–type virus that infects both avian and mammalian species,” Baric says. “There aren’t any other coronaviruses that I know can do this.” Some virologists have labeled the Hong Kong delta coronvirus a pandemic threat. The Haitian virus differs considerably and virologists want to test local children and adults for antibodies to it. If its ability to infect people is confirmed, it may also be viewed as a pandemic threat, Saif says. Together, the two reports point to the importance of animal diseases in public health, and the need for coronavirus vaccines for domesticated animals. “This research clearly shows that more studies are desperately needed to evaluate critical questions regarding the frequency of cross-species [coronavirus] transmission and potential for human-to-human spread,” Baric says. Gregory Gray at Duke University, senior author on the Malaysian chimeric coronavirus study, also advocates for surveillance among pneumonia patients in areas known to be hot spots for novel viruses or places where large populations of animals and humans mix, such as live animal markets and large farms. “These spillovers take years,” Gray says. “It’s not like in the movies. They go through different steps to infect humans.” So far indications are that the chimeric virus has not evolved to transmit efficiently between people.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

December 18, 2020 10:24 PM

|

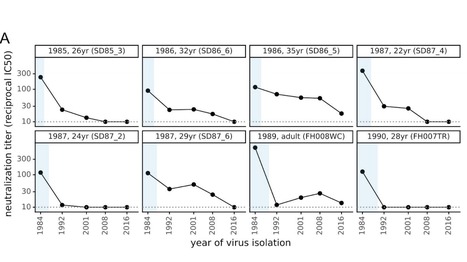

There is intense interest in antibody immunity to coronaviruses. However, it is unknown if coronaviruses evolve to escape such immunity, and if so, how rapidly. Here we address this question by characterizing the historical evolution of human coronavirus 229E. We identify human sera from the 1980s and 1990s that have neutralizing titers against contemporaneous 229E that are comparable to the anti-SARS-CoV-2 titers induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination. We test these sera against 229E strains isolated after sera collection, and find that neutralizing titers are lower against these "future" viruses. In some cases, sera that neutralize contemporaneous 229E viral strains with titers >1:100 do not detectably neutralize strains isolated 8-17 years later. The decreased neutralization of "future" viruses is due to antigenic evolution of the viral spike, especially in the receptor-binding domain. If these results extrapolate to other coronaviruses, then it may be advisable to periodically update SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Preprint available in bioRxiV (Dec. 18, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.17.423313

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

November 8, 2020 1:23 PM

|

There are at least 50 million confirmed coronavirus cases across the globe. With about 10 million of those cases, the United States is the country with the most confirmed coronavirus cases, followed immediately by India and Brazil. At least 230,000 people have died from the disease in the United States. The World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a pandemic on March 11. The coronavirus has killed more Americans than every war US troops have died in since 1945 combined, Business Insider's John Haltiwanger reported. The leading cause of death for Americans, heart disease, typically kills fewer than 650,000 people a year in the US. The pandemic has created uncertainty and instability, leading to roiled markets, shuttering many small businesses nationwide, and forcing the world to adapt to a new normal. For nearly nine months, people have been learning to live under once unfamiliar laws and recommendations from health officials. Quarantining, practicing social distancing, and wearing masks have become the relative norm in most countries. But as the numbers of confirmed coronavirus cases and deaths continue to rise, health officials say practices will remain the new norm well into 2021 and possibly 2022. Meanwhile, scientists and pharmaceutical companies have been racing to create a vaccine to prevent COVID-19. But it will take more time to release safe and effective shots — and even longer to inoculate enough of the global population to achieve herd immunity.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

August 28, 2020 11:41 AM

|

The main protease, Mpro (or 3CLpro) in SARS-CoV-2 is a viable drug target because of its essential role in the cleavage of the virus polypeptide. Feline infectious peritonitis, a fatal coronavirus infection in cats, was successfully treated previously with a prodrug GC376, a dipeptide-based protease inhibitor. Here, we show the prodrug and its parent GC373, are effective inhibitors of the Mpro from both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 with IC50 values in the nanomolar range. Crystal structures of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with these inhibitors have a covalent modification of the nucleophilic Cys145. NMR analysis reveals that inhibition proceeds via reversible formation of a hemithioacetal. GC373 and GC376 are potent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 replication in cell culture. They are strong drug candidates for the treatment of human coronavirus infections because they have already been successful in animals. The work here lays the framework for their use in human trials for the treatment of COVID-19. Coronavirus main protease is essential for viral polyprotein processing and replication. Here Vuong et al. report efficient inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication by the dipeptide-based protease inhibitor GC376 and its parent GC373, which were originally used to treat feline coronavirus infection. Published in Nature Commun. (August 27, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18096-2

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

August 10, 2020 12:04 PM

|

The report, published by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children's Hospital Association, said there was a 40% increase in child cases across the states and cities that were studied in those two weeks there was a 40% increase in child cases across the states and cities that were studied. The age range for children differed by state, with some defining children as only those up to age 14 and one state -- Alabama -- pushing the limit to 24. The compiled data comes during back-to-school season as health officials are trying to understand the effects of the virus on children and the role young people play in its spread. Some schools have begun welcoming crowds back to class and others have had to readjust their reopening plans in response to infections. In one Georgia high school that made headlines after a photo of a crowded school hallway went viral, nine coronavirus cases were reported, according to a letter from the principal. Six of those cases were students and three were staff members, the letter said. While some US leaders -- including the President -- have said the virus doesn't pose a large risk to children, one recent study suggests older children can transmit the virus just as much as adults. Another study said children younger than 5 carry a higher viral load than adults, raising even more questions about their role in transmission. At least 86 children have died since May, according to the new report. Last week, a 7-year-old boy with no pre-existing conditions became the youngest coronavirus victim in Georgia. In Florida, two teenagers died earlier this month bringing the state's death toll of minors to seven. And Black and Hispanic children are impacted more severely with higher rates of infections, hospitalizations and coronavirus-related complications, recently published research shows.

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 23, 2020 11:20 AM

|

Watchdogs expressed concern that Pfizer and BioNTech's recent vaccine supply deal with the U.S. could lead to price gouging on the final shot. The U.K. pumped $127 million into its vaccine manufacturing capacity, plus the EMA formed a multi-pronged COVID-19 research initiative. And the NIH will launch a suite of large-scale coronavirus therapeutics trials. With a new U.S. vaccine supply deal under their belts, Pfizer and BioNTech are taking heat from some watchdogs concerned that the partners' shot is overpriced—and worried by Pfizer's refusal to promise a no-profit vaccine. China's Sinopharm said its shot could release to the public before year's end; plus, the U.K. poured nearly $127 million into manufacturing "for any successful" COVID vaccine, approval pending. Meanwhile, the National Institutes of Health is gearing up to launch a "flurry" of large-scale COVID-19 therapeutics trials, and the European Medicines Agency established a new coronavirus research initiative. Pfizer and BioNTech's $1.95 billion deal to supply 100 million vaccine doses to the U.S. drew ire from watchdogs, who warned that the move could lead to price-gouging later. The agreement includes an option for 500 million more doses at an as-yet-undetermined price. AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson both pledged to sell vaccines at no profit to the U.S.—which has shelled out funding for development in both cases—while Pfizer has expressed interest in making at least a marginal return on its shot.....

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 29, 2020 11:45 AM

|

Scientists not involved in the study seriously doubt the findings, which challenge the current consensus on where and when the virus originated. In a study not yet published in a journal, scientists have reported that the new coronavirus was present in wastewater in Barcelona, Spain in March 2019, a finding that, if confirmed, would show that the pathogen had emerged much earlier than previously thought. But independent experts who reviewed the findings said they doubted the claim. The study was flawed, they said, and other lines of evidence strongly suggest the virus emerged in China late last year. Up until now, the earliest evidence of the virus anywhere in the world has been from December 2019 in China and it was only known to have hit mainland Spain in February 2020. “Barcelona is a city that is frequented by Chinese people, in tourism and business, so probably this happened also elsewhere, and probably at the same time,” said the lead author, Albert Bosch, a professor in the Department of Microbiology of the University of Barcelona who has been studying viruses in wastewater for more than 40 years. Several experts not involved in the research pointed out problems with the new study, which has not yet been subjected to the critical review by outside experts that occurs before publication in a scientific journal. They suggested that the tests might very well have produced false positives because of contamination or improper storage of the samples. “I don’t trust the results,” said Irene Xagoraraki, an environmental engineer at Michigan State University. Researchers at the University of Barcelona posted their findings online on June 13. Most of their report described research on wastewater treatments from early 2020. Preprint available at medRxiv (June 13, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.13.20129627

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 7, 2020 12:54 PM

|

On January 9 of this year, Chinese state media reported that a team of researchers led by Xu Jianguo had identified the pathogen behind a mysterious outbreak of pneumonia in Wuhan as a novel coronavirus. Although the virus was soon after named 2019-nCoV, and then renamed SARS-CoV-2, it remains commonly known simply as the coronavirus. While that moniker has been catapulted into the stratosphere of public attention, it’s somewhat misleading: Not only is it one of many coronaviruses out there, but you’ve almost certainly been infected with members of the family long before SARS-CoV-2’s emergence in late 2019. Coronaviruses take their name from the distinctive spikes with rounded tips that decorate their surface, which reminded virologists of the appearance of the sun’s atmosphere, known as its corona. Various coronaviruses infect numerous species, but the first human coronaviruses weren’t discovered until the mid-1960s. “That was sort of the golden days, if you will, of virology, because at that time the technology became available to grow viruses in the laboratory, and to study viruses in the laboratory,” says University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center pediatrician Jeffrey Kahn, who studies respiratory viruses. But the two coronaviruses that were identified at the time, OC43 and 229E, didn’t elicit much research interest, says Kahn, who wrote a review on coronaviruses a few years after the SARS outbreak of 2003. “I don't believe there was a big effort to make vaccines against these because these were thought to be more of a nuisance than anything else.” The viruses cause typical cold symptoms such as a sore throat, cough, and stuffy nose, and they seemed to be very common; one early study estimated that 3 percent of respiratory illnesses in a children’s home in Georgia over seven years in the 1960s had been caused by OC43, and a 1986 study of children and adults in northern Italy found that it was rare to come across a subject who did not have antibodies to that virus (an indicator of past infection)......

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...