Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

December 17, 11:46 AM

|

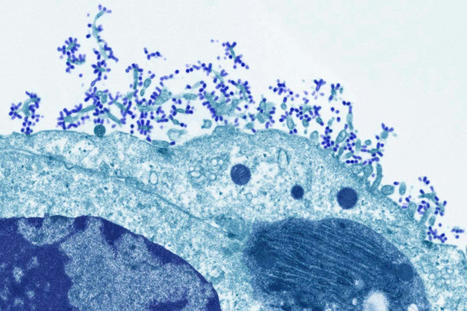

Scientists are deploying an array of technologies that are making a vaccine against all varieties of influenza seem more achievable. In February 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) tried to predict which strains of influenza were going to pose the biggest threat in that year’s Northern Hemisphere flu season. It failed. On the basis of surveillance data on which strains were circulating, the WHO selected four that would become the foundation of that year’s vaccine. One was an H3N2 virus strain that was the most prevalent of that particular subtype, at that moment. But by the time the vaccine was making its way into people’s arms that autumn, a different version of the virus had taken over — and the vaccine was only 6% effective at protecting against it. That year’s Northern Hemisphere flu season was more severe than the five that had preceded it, and lasted weeks longer than any in the previous decade.This problem of antigenic drift — when gene mutations cause components of the influenza virus to change, and it evolves away from the vaccines designed to keep it in check — could be reduced by the development of a universal flu vaccine. A shot that provides broad coverage against a wide array of strains could improve efficacy significantly from the 40–60% reduction in risk that flu vaccines typically achieve. It would also eliminate the need for WHO’s twice-yearly meetings to predict which viral strains to guard against, the subsequent scramble to manufacture the vaccine and the need for people to be vaccinated year after year. Some strategies to improve the effectiveness of the flu vaccine and reduce the need for annual shots have made it into early clinical trials. A major thrust of these efforts is to coax the immune system to respond to a part of the flu virus that it normally pays little attention to. Ordinarily, the immune system produces antibodies that focus on a particular part of haemagglutinin, a protein on the surface of the virus that allows it to enter cells. Antibodies clamp to haemagglutinin and block the virus from attaching. Haemagglutinin has 18 subtypes: H1 to H18. And, unfortunately, haemagglutinin can evolve rapidly, changing its shape so that antibodies can no longer bind to it. “What we’re trying to do is trick the immune system into attacking a part of the influenza virus that it typically doesn’t attack,” says Florian Krammer, a vaccinologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Haemagglutinin is a stalk, rising from the virus surface, topped by a ball-shaped head. The immune system focuses most of its efforts here. “The head domain sticks out of the virus, so it’s very easy for B-cell receptors, which in the end become antibodies, to recognize that part,” Krammer says. “The stalk is a little bit more hidden.” Krammer treats this as a challenge, and is trying to amplify the immune response to the haemagglutinin stalk. A second protein called neuraminidase, which helps the virus spread to other cells, has 11 subtypes. Although viruses with any combination of these haemagglutinin and neuraminidase subtypes can infect people, the two currently circulating in humans are H1N1 and H3N2. Krammer and his colleagues create new versions of the virus by taking H1 stalks and replacing the heads with those from other subtypes, such as H14 or H8. Apart from newborn babies, most people have been either infected with or vaccinated against flu — or both — and so have a pre-existing immune response. When presented with a chimaera protein (say, an H1 stalk and an H8 head) the immune system recognizes the part it has seen before (the stalk)and reacts to that. “That weakens the response to the head and strengthens the response to this stalk,” Krammer says. And a stronger reaction to the stalk should, in turn, make it harder for the virus to evade the immune response. The stalk plays a crucial part in allowing the virus to fuse with the host cell, and undergoes a series of structural changes during fusion. Any mutation that interferes with those changes renders the virus ineffective, meaning the stalk can’t evolve in response to the immune system as readily as the head can. The stalk also doesn’t vary much between virus strains, so immunity against this part provides broader protection. In 2020, Krammer and his colleagues tested a vaccine in a small phase I clinical trial3. They showed that it induced a large number of antibodies to target an H1 stalk. Although the COVID-19 pandemic put the work on hold, it has since resumed. The next step will be to try the same with an H3 stalk, and to combine the two to see whether the result generates a broad antiviral response. “It’s going slowly, but it’s going,” Krammer says. At Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, microbiologist Nicholas Heaton is also trying to get the immune system to look beyond the haemagglutinin head. His aim is to get it to notice other sites on the virus at which antibodies can bind, known as epitopes. “Normally, the immune system would focus on that haemagglutinin head domain. It’s obsessed with it,” Heaton says. “If you remove it, then you say, out of everything that’s left, what do you like? And so you get these responses to other epitopes.” Heaton and his colleagues used gene editing to create more than 80,000 variations of haemagglutinin with different changes to a specific part of the head domain, but with the same stalk4. The variety of head-domain epitopes meant that the immune system focused its attention on the stalk, leading to a significant increase in stalk antibodies when tested in ferrets and mice. But Heaton didn’t want to create a new immune response at the expense of the old one. He, therefore, also used conventional methods to create a virus particle that elicited the typical haemagglutinin-head-focused response, and then mixed the two types to achieve broader immunity. The variant epitopes also seem to induce some immunity, and many might help to inhibit the virus. The stalk-binding antibodies don’t actually neutralize the virus, Heaton says, but they can help the immune system to recognize it and clear it faster, theoretically lowering the viral burden and thus the severity of the infection. “People who would have stayed out of work for two days won’t even feel sick,” Heaton says. People who might have died could instead experience just a few days of illness. “Those are the types of shifts that we think would be accomplished by lower peak viral burden and faster clearance of the virus.”.....

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

September 22, 2020 2:53 PM

|

A new Cleveland Clinic study has found that receiving the influenza vaccine does not increase a person's risk for contracting COVID-19 or worsen associated morbidity or mortality. Published in the Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, the study shows the flu vaccine is the single most important intervention to help stay healthy this fall and winter. Seasonal flu activity is unpredictable, and otherwise healthy people are hospitalized due to serious respiratory infection each year. This year, it's even more important to receive the flu vaccination to help prevent a twindemic of flu and COVID-19. In this new study, a team of researchers led by Joe Zein, M.D. - a pulmonologist at Cleveland Clinic—analyzed more than 13,000 patients tested for COVID-19 at Cleveland Clinic between early March and mid-April of this year. Comparing those who had received unadjuvanted influenza vaccines in the fall or winter of 2019 (4,138 patients) against those who did not received the vaccine (9,082 patients) revealed that influenza vaccination was not associated with increased COVID-19 incidence or disease severity, including risk for hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit or mortality. "Our findings suggest that we should proceed as usual with our vaccination strategy for global influenza this flu season," said Dr. Zein. "Getting the annual flu vaccine remains the best safeguard against the influenza virus—both for yourself and the people around you." Since much is still unknown about the possible outcomes of concurrent SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) and influenza infection—including disease pathology and burden to the healthcare system—researchers and clinicians believe that the population's adherence to widespread and early flu vaccination while researchers continue to collect data will help to mitigate the risk of simultaneous viral infections and epidemics/pandemics. "We have already seen the stress that COVID-19 can put on our hospitals and resources," said Dr. Zein. "While we're not yet sure how flu season will affect COVID-19 susceptibility and infections, we strongly advise people to get their influenza vaccines, both for their individual health and the collective health of our care systems." This study is the latest to utilize data from patients enrolled in Cleveland Clinic's COVID-19 Registry, which includes all individuals tested at Cleveland Clinic for the disease, not just those that test positive. Cleveland Clinic was one of the first organizations to develop a data registry and biobank for the emergent disease. Data from the registry has already been used in several landmark COVID-19 studies, including those that have led to the development of models that can predict a patient's likelihood of testing positive for COVID-19 and being hospitalized due to the disease. Original study published in J. Clin. and Translational Science (Sept. 17, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2020.543

|

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

November 25, 2022 11:42 AM

|

An mRNA vaccine has been found to induce antibody responses against all 20 known subtypes of influenza A and B in mice and ferrets. An experimental vaccine has generated antibody responses against all 20 known strains of influenza A and B in animal tests, raising hopes for developing a universal flu vaccine. Influenza viruses are constantly evolving, making them a moving target for vaccine developers. The annual flu vaccines available now are tailored to give immunity against specific strains predicted to circulate each year. However, researchers sometimes get the prediction wrong, meaning the vaccine is less effective than it could be in those years. Some researchers think annual flu jabs could be replaced by a universal flu vaccine that is effective against all flu strains. Researchers have tried to achieve this by making vaccines containing protein fragments that are common to several influenza strains, but no universal vaccine has yet gained approval for wider use. Now, Scott Hensley at the University of Pennsylvania and his colleagues have created a vaccine based on mRNA molecules – the same approach that was pioneered by the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna covid-19 vaccines. mRNA contains genetic codes for making proteins, just like DNA. The vaccine contains mRNA molecules encoding fragments of proteins found in all 20 known strains of influenza A and B – the viruses that cause seasonal outbreaks each year. The strains have different versions of two proteins on their surface, haemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N), which are targeted by immune responses. But even within one strain, such as H1N1, there can be slight variations in these proteins, so the version in the universal vaccine will not exactly match every possible variant. In tests in mice, the team found that the animals generated antibodies specific to all 20 strains of the flu virus, and these antibodies remained at a stable level for up to four months. In another test, the team gave mice the universal flu vaccine or a dummy vaccine containing code for a non-flu protein. A month later, they infected them with either one of two variants of the H1N1 flu virus, one with an H1 protein that was very similar to the version of the protein in the vaccine, and one with a more distinct version. All the mice given the flu vaccine survived exposure to the virus with the more similar protein and 80 per cent survived being infected with the more distinct variant. All of the mice given the dummy vaccine died around a week after infection with either variant. Another group of mice were given an mRNA vaccine targeted only to the precise flu strain they were exposed to, and all of this group survived over the same time period. This suggests the universal flu vaccine would offer less protection against new variants of the 20 flu strains than an annual vaccine matched to new forms of the virus, says Albert Osterhaus at the University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover in Germany, who wasn’t involved in the study. The researchers also tested the universal vaccine in ferrets with similar results. “The mouse and ferret models for influenza are as good as animal models get. The animal data are promising and thus a good indication of what will happen in humans,” says Peter Palese at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. A key benefit of mRNA vaccines is that they can easily be scaled up compared with other approaches which rely on growing influenza viruses in chicken eggs or in the lab, says Palese. “For generating a basic immunity against epidemic or pandemic influenza virus strains in the future, this strategy could offer an option if longevity [of immunity] in humans is confirmed,” says Osterhaus. “Definitely these animal data are promising and merit further exploration in clinical studies. Given previous studies with candidate universal flu vaccines in human trials, it is hard to predict what the clinical data will bring,” says Osterhaus. “This 20-HA mRNA vaccine was tested in ferret animals, which is highly significant and may hold promise for protecting against future emerging flu strains against severe disease in humans,” says Sang-Moo Kang at Georgia State University. Study cited published in Science (Nov. 24): https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abm0271

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

September 30, 2019 2:52 PM

|

The dominant flu strain circulating the world appears to have changed since the World Health Organization decided which one to base shots on in February, a Canadian flu expert warns. - Flu circulates the world annually and becomes active in the US around October

- WHO scientists chose the forms of the virus to base vaccines on in February for the Northern Hemisphere and this month for the Southern Hemisphere

- Last week the WHO predicted different strains of the flu would be dangerous to the Southern Hemisphere from the ones they based Northern shots on

- That may mean the North's shot will be 'mismatched'

- A mismatched vaccine for influenza A/H3N2 is partially blamed for the record deaths from the 2017-2018 flu season

This year's flu vaccine may not be effective, a top expert warns. Dr Danuta Skowronski, an influenza expert from the University of British Columbia told Stat News that the this year's flu shot for the Northern Hemisphere - including the US, UK and Canada - is likely to be a 'mismatch.' Flu shots have to be newly developed ahead of each season based on scientists' predictions of which strains will be most active in the coming months. Officials from the World Health Organization (WHO) choose the strains for the Northern Hemisphere's shot in February, and chose those for the Southern Hemisphere last week. For the Southern Hemisphere, officials chose influenza A/H3N2 and B/Victoria - different ones from the strains picked for the North, suggesting to Dr Skowronski that the prior prediction was wrong and the Northern shots may be ineffective. 'I think the vaccine strain selections by the WHO committee are obviously important for the Southern Hemisphere but they’re also signals to us because they’re basing their decisions on what they see current predominating on the global level,' said Dr Skowronski. Every year, the flu virus makes its way around the world, typically becoming more active in the US in October. Without fail, between three and five million people fall ill globally and anywhere between 290,000 and 650,000 die of the disease. Most of those that die are very young, very old or have an underlying condition. But in the worst flu seasons, a healthy people succumb to the virus as well. Already, one child has died of the flu in the US - an alarming bellwether that the US may be in for a particularly bad season. The 2017-2018 flu season was one of those particularly nasty years for the flu. More than 80,000 people died of flu in the US that season, including 160 children. It was the highest death toll since 1976, and pediatric deaths set an all-time record, aside from pandemics like the 1918 Spanish flu, which killed between 20 and 100 million worldwide. The historically high fatality rate from the 2017-2018 flu season was largely blamed on the fact that the flu shots distributed to the US were a poor match for the circulating strains of the virus. Flu vaccines are the best protection there is against the flu - but they are only effective against the strains of the virus upon which they're based - and that's a matter of calculated guesswork. It's impossible to quantify exactly how many strains of flu there are. The most common viruses are influenza A and B, but there are others, they vary based on the hosts they first attack (swine, bird etc) and mutate frequently. Ahead of each season, health officials and flu experts the world over convene to carefully examine early cases of the flu in each season and the patterns from the previous years to predict which strains and variations will be dominant that year. Flu vaccines are then developed based on either a dead form of those viruses or partial viruses. When scientists' predictions are close, the vaccines are highly effective, and fewer people die - so long as vaccination rates remain high. When they're off-base, illnesses surge and death tolls climb. These predictions are tricky, as the strains of the virus vary from continent-to-continent and the ways they move from one to the other vary annually. But typically, the most potent and common ones are similar in the North and South. Flu season starts earlier in the year in the Northern Hemisphere, so WHO officials convened in February to decide what strains should be the basis of the Northern shot. After narrowing down the viruses to influenza B/Victoria and A/H3N2, the scientists struggled to make a choice about which particular variation of the H3N2 virus would pose the greatest threat in the 2019-2020 flu season, Stat reported. So they went with the virus type that had suddenly ramped up at the end of last season in the US. But Dr Skowronski thinks that that might have been a mistake. 'That H3N2 wave was late and it was evolving at the time that they met in February,' Skowronski said. 'And there was a diverse mix of H3 viruses. And it wasn’t clear to them, I guess, [which strain] … would emerge the clear winner,' she told Stat. But by the time the officials met again this month to decide the basis for the Southern Hemisphere's shot, things had changed. H3N2 has posed a shot-matching challenge in recent years. It was the same virus that the 2017-2018 shots offered such little protection - only about 40 percent - against that season's dominant, and particularly aggressive strain. Dr Skowronski would like to see the Northern Hemisphere's shot re-formulated, based on the Southern Hemisphere shot. But shorty of that, she urges that doctors be prepared that even people who get inoculated against the flu may wind up contracting it this year any way. At least, however, the influenza B virus predicted in February appears to still be the correct one, which is particularly important as children tend to contract and die from B strains more often. Last week, officials from the World Health Organization chose the strains of the virus upon which to base the Southern Hemisphere's vaccine Strains recommendations available at the WHO site: https://www.who.int/influenza/vaccines/virus/recommendations/en/

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...