Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

February 25, 12:00 PM

|

Bats are reservoirs for multiple viruses, some of which are known to cause global disease outbreaks. Virus spillovers from bats have been implicated in zoonotic transmission. Some bat species can tolerate viral infections, such as infections with coronaviruses and paramyxoviruses, better than humans and with less clinical consequences. Bat species are speculated to have evolved alongside these viral pathogens, and adaptations within the bat immune system are considered to be associated with viral tolerance. Inflammation and cell death in response to zoonotic virus infections prime human immunopathology. Unlike humans, bats have evolved adaptations to mitigate virus infection-induced inflammation. Inflammatory cell death pathways such as necroptosis and pyroptosis are associated with immunopathology during virus infections, but their regulation in bats remains understudied. This review focuses on the regulation of inflammation and cell death pathways in bats. We also provide a perspective on the possible contribution of cell death-regulating proteins, such as caspases and gasdermins, in modulating tissue damage and inflammation in bats. Understanding the role of these adaptations in bat immune responses can provide valuable insights for managing future disease outbreaks, addressing human disease severity, and improving pandemic preparedness. Published (Feb. 21, 2025):

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

January 9, 12:29 PM

|

The zoonotic transmission of bat coronaviruses poses a threat to human health. However, the diversity of bat-borne coronaviruses remains poorly characterized in many geographical areas. Here, we recovered six complete coronavirus genomes by performing a metagenomic analysis of fecal samples from hundreds of individual bats captured in Spain, a country with high bat species diversity. Three of these genomes corresponded to potentially novel coronavirus species belonging to the alphacoronavirus genus. Phylogenetic analyses revealed that some of these viruses are closely related to coronaviruses previously described in bats from other countries, suggesting the existence of a shared viral reservoir worldwide. Using viral pseudotypes, we investigated the receptor usage of the identified viruses and found that one of them can use human and bat ACE2, highlighting its zoonotic potential. However, the receptor usage of the other viruses remains unknown. This study broadens our understanding of coronavirus diversity and identifies research priorities for the prevention of zoonotic viral outbreaks. Preprint in biorXiv (Jan. 8, 2025): https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.01.07.631674

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

April 27, 2024 1:41 PM

|

By cutting trees in response to international demand for tobacco, farmers induced wildlife to start eating virus-laden bat guano. Zoonotic diseases, or illnesses transmitted from animals to humans, account for about three quarters of new infectious diseases around the world, including some that could lead to pandemics. The risk of a pathogen jumping from an animal to a human increases when people encroach on ecosystems and cause relationships to be disrupted between species—but how that risk actually becomes a reality can be unpredictable and difficult to untangle. A new paper published this week in Communications Biology shines rare light on one such case study: an example showing how international demand for tobacco led to habitat alterations in Uganda that seemingly drove chimpanzees and other species to begin consuming bat guano for mineral nutrients. In that process, the animals might have been exposed to more than two dozen viruses, including a novel cousin of the COVID-causing pathogen SARS-CoV-2...

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

January 8, 2023 6:44 PM

|

Parts of Southeast Asia where human and bat population densities are highest could be infection hotspots, a study finds. Tens of thousands of people in Southeast Asia could be infected with coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV-2 each year, a study published yesterday (August 9) in Nature Communications estimates. The research, which first appeared as a preprint last September, analyzed the geographic ranges of 26 bat species and found their habitat overlapped regions where half a billion people live, representing an area larger than 5 million square kilometers, reports Reuters. Analyzing that data along with estimates of the number of people who exhibited detectable coronavirus antibodies predicted that approximately 66,000 potential infections occur each year. Stephanie Seifert, a virus ecologist at Washington State University in Pullman who was not involved in the research, tells Nature that the work “highlights how often these viruses have the opportunity to spillover.” The study coauthors considered the geographic ranges of bats known to host SARS-related viruses—primarily horseshoe bats (family Rhinolophidae) and Old World leaf-nosed bats (family Hipposideridae). They found hot spots of potential spillover events in southern China, parts of Myanmar, and the Indonesian island of Java—where both bat and human populations are particularly dense, reports Nature. Most of these SARS-related viruses don’t easily spread among humans or cause illness. But study coauthor Peter Daszak tells Nature that with enough infections “raining down on people, you will eventually get a pandemic.” However, Alice Hughes, a conservation biologist at the University of Hong Kong who was not involved in the work, tells Nature that this analysis relies on outdated and low-resolution geographical range data. “What they are trying to do is very valuable and needs to be done, but it has to be done with more finesse,” she says. The study authors argue their research can focus spillover monitoring to high-risk regions in order to identify outbreaks sooner. Renata Muylaert, a disease ecologist at Massey University in New Zealand who was not involved in the research, agrees, telling Nature, “The article has considerable significance for surveillance.” This analysis looked only at bat-to-human spillover events and did not consider infections that first transmit from bats to an intermediate animal and later to humans. Daszak tells Nature that there were limited data on that type of event, but that including them would have “massively increased the estimated risk of spillovers.”

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

November 17, 2022 12:51 PM

|

Landmark study reveals ‘spillover’ mechanism for the rare but deadly Hendra virus. “Hey guys, could you open your wings and show me?” says Peggy Eby, looking up at a roost of flying foxes in Sydney’s Botanical Gardens. “I talk to them a lot.” Eby, a wildlife ecologist at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, is looking for lactating females and their newborn pups, but the overcast weather is keeping them snuggled under their mothers’ wings. Eby has been studying flying foxes, a type of bat, for some 25 years. Using her binoculars, she tallies the number of lactating females that are close to weaning their young — a proxy for whether the bats are experiencing nutritional stress and so probably more likely to shed viruses that can make people ill. Australian flying foxes are of interest because they host a virus called Hendra, which causes a very rare but deadly respiratory infection that kills one in every two infected people. Hendra virus, like Nipah, SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic) is a bat virus that has spilled over into people. These viruses often reach humans through an intermediate animal, sometimes with deadly consequences. Scientists know that spillovers are associated with habitat loss, but have struggled to pinpoint the specific conditions that spark events until now. After a detailed investigation, Eby and her colleagues can now predict — up to two years ahead — when clusters of Hendra virus spillovers will probably appear. “They have identified the environmental drivers of spillover,” says Emily Gurley, an infectious-diseases epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. And they have determined how those events could be prevented. The results are published in Nature on 16 November1. Food stress Specifically, the researchers found that clusters of Hendra virus spillovers occur following years in which the bats experience food stress. And these food shortages typically follow years with a strong El Niño, a climatic phenomenon in the tropical Pacific Ocean that is often associated with drought along eastern Australia. But if the trees the bats rely on for food during the winter have a large flowering event the year after there’s been a food shortage, there are no spillovers. Unfortunately, the problem is that “there’s hardly any winter habitat left”, says Raina Plowright, a disease ecologist and study co-author at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. The study is “absolutely fantastic”, says Sarah Cleaveland, a veterinarian and infectious-disease ecologist at the University of Glasgow, UK. “What’s so exciting about it is that it has led directly to solutions.” Cleaveland says the study’s approach of looking at the impact of climate, environment, nutritional stress and bat ecology together could bring new insights to the study of other pathogens, including Nipah and Ebola, and their viral families. The study provides “a much clearer understanding of drivers of this issue, with broad relevance to pandemics elsewhere”, says Alice Hughes, a conservation biologist at the University of Hong Kong. “The paper underscores the enhanced risk we are likely to see” with climate change and increasing habitat loss, she says. Urban shift Hendra virus was identified in 1994, following an outbreak in horses and people at a thoroughbred training facility in Brisbane, Australia. Studies later established that the virus spreads from its bat reservoir — most likely the black flying fox (Pteropus alecto) — to horses through faeces, urine and spats of chewed-up pulp the flying foxes spit out on the grass. Infected horses then spread the virus to people. Infections typically occur in clusters during the Australian winter, and several years can go by before another cluster emerges in horses, but cases have been picking up since the early 2000s. To study the mechanism of spillovers, Plowright, Eby and their colleagues collected data on the location and timing of such events, the location of bat roosts and their health, climate, nectar shortages and habitat loss over some 300,000-square kilometres in southeast Australia from 1996 to 2020. Then they used modelling to determine which factors were associated with spillovers. “I’m just in awe of the invaluable data sets that they have on the ecology,” says Gurley. Over the course of the study, the team noticed significant changes in the bats’ behaviour. The flying foxes went from having predominantly nomadic lifestyles — moving in large groups from one native forest to the other in search of nectar — to settling in small groups in urban and agricultural areas, bringing the bats closer to where horses and people live. The number of occupied bat roosts in general has trebled since the early 2000s to around 320 in 2020. A separate study from the team2 found that the newly established roosts shed Hendra virus every winter, but in years following a food shortage bats shed more virus. There were “really dramatic winter spikes in infection”, says co-author Daniel Becker, an ecologist who focuses on infectious diseases at the University of Oklahoma in Norman. The study also linked increased viral shedding in bats to increased spillovers to horses. In search of nectar Modelling in Plowright and Eby’s most recent Nature paper shows that flying-fox populations split into small groups that migrated to agricultural areas close to horses when food was scarce, and that food shortages followed strong El Niño events, probably because native eucalyptus tree budding is sensitive to climate changes. To conserve energy, the bats fly only small distances in these years, scavenging for food in agricultural areas near horses. Spillovers to horses were most likely to occur in winters following a food shortage, says Plowright. Their model was able to accurately predict in which years these would occur. Then something unexpected happened. An El Niño occurred in 2018 followed by a drought in 2019, suggesting that 2020 should also have been a spillover year. But there was only one event in May and none has been detected since. “We threw all the cards back up into the air and looked carefully at all the other elements of our hypothesis,” says Eby. Eventually they discovered that when native forests have major flowering events in winters following a food shortage, this helps to avert spillovers. In 2020, a red-gum forest near the town of Gympie flowered, drawing in some 240,000 bats. And similar winter flowering events occurred in other regions in 2021 and 2022. The researchers suggest that these mass migrations take the bats away from horses. They propose that by restoring the habitats of those handful of species that flower in winter, fewer spillovers in horses, and potentially in people, would occur. And by restoring the habitats of other animals that host dangerous pathogens, “maybe we can prevent the next pandemic”, says Plowright. Published in Nature: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-03682-9

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 6, 2021 2:51 AM

|

Scientists have detected Zika virus RNA in free-ranging African bats. RNA, or ribonucleic acid, is a molecule that plays a central role in the function of genes. A team of Colorado State University scientists, led by veterinary postdoctoral fellow Dr. Anna Fagre, has detected Zika virus RNA in free-ranging African bats. RNA, or ribonucleic acid, is a molecule that plays a central role in the function of genes. According to Fagre, the new research is a first-ever in science. It also marks the first time scientists have published a study on the detection of Zika virus RNA in any free-ranging bat. The findings have ecological implications and raise questions about how bats are exposed to Zika virus in nature. The study was recently published in Scientific Reports, a journal published by Nature Research. Fagre, a researcher at CSU's Center for Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases, said while other studies have shown that bats are susceptible to Zika virus in controlled experimental settings, detection of nucleic acid in bats in the wild indicates that they are naturally infected or exposed through the bite of infected mosquitoes. "This provides more information about the ecology of flaviviruses and suggests that there is still a lot left to learn surrounding the host range of flaviviruses, like Zika virus," she said. Flaviviruses include viruses such as West Nile and dengue and cause several diseases in humans. CSU Assistant Professor Rebekah Kading, senior author of the study, said she, Fagre and the research team aimed to learn more about potential reservoirs of Zika virus through the project. The team used 198 samples from bats gathered in the Zika Forest and surrounding areas in Uganda and confirmed Zika virus in four bats representing three species. Samples used in the study date back to 2009 from different parts of Uganda, years prior to the large outbreaks of Zika virus in 2015 to 2017 in North and South Americas. "We knew that flaviviruses were circulating in bats, and we had serological evidence for that," said Kading. "We wondered: Were bats exposed to the virus or could they have some involvement in transmission of Zika virus?" The virus detected by the team in the bats was most closely related to the Asian lineage Zika virus, the strain that caused the epidemic in the Americas following outbreaks in Micronesia and French Polynesia. The first detection of the Asian lineage Zika virus in Africa was in late 2016 in Angola and Cape Verde. "Our positive samples, which are most closely related to the Asian lineage Zika virus, came from bats sampled from 2009 to 2013," said Fagre. "This could mean that the Asian lineage strain of the virus has been present on the African continent longer than we originally thought, or it could mean that there was a fair amount of viral evolution and genomic changes that occurred in African lineage Zika virus that we were not previously aware of." Fagre said the relatively low prevalence of Zika virus in the bat samples indicates that bats may be incidental hosts of Zika virus infection, rather than amplifying hosts or reservoir hosts. "Given that these results are from a single cross-sectional study, it would be risky and premature to draw any conclusions about the ecology and epidemiology of this pathogen, based on our study," she said. "Studies like this only tell one part of the story." The research team also created a unique assay for the study, focusing on a specific molecular component that flaviviruses possess called subgenomic flavivirus RNA, sfRNA. Most scientists that search for evidence of Zika virus infection in humans or animals use PCR, polymerase chain reaction, to identify bits of genomic RNA, the nucleic acid that results in the production of protein, said Fagre. Kading said her team will continue their research to try and learn more about how long these RNA fragments persist in tissues, which will allow them to approximate when these bats were infected with Zika virus. "There is always a concern about zoonotic viruses," she said. "The potential for another outbreak is there and it could go quiet for a while. We know that in the Zika forest, where the virus was first found, the virus is in non-human primates. There are still some questions with that as well. I don't think Zika virus has gone away forever." See Scientific Reports (April 26, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87816-5

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

February 10, 2020 11:23 PM

|

It’s no coincidence that some of the worst viral disease outbreaks in recent years — SARS, MERS, Ebola, Marburg and likely the newly arrived 2019-nCoV virus — originated in bats. A new University of California, Berkeley, study finds that bats’ fierce immune response to viruses could drive viruses to replicate faster, so that when they jump to mammals with average immune systems, such as humans, the viruses wreak deadly havoc. Some bats — including those known to be the original source of human infections — have been shown to host immune systems that are perpetually primed to mount defenses against viruses. Viral infection in these bats leads to a swift response that walls the virus out of cells. While this may protect the bats from getting infected with high viral loads, it encourages these viruses to reproduce more quickly within a host before a defense can be mounted. This makes bats a unique reservoir of rapidly reproducing and highly transmissible viruses. While the bats can tolerate viruses like these, when these bat viruses then move into animals that lack a fast-response immune system, the viruses quickly overwhelm their new hosts, leading to high fatality rates. “Some bats are able to mount this robust antiviral response, but also balance it with an anti-inflammation response,” said Cara Brook, a postdoctoral Miller Fellow at UC Berkeley and the first author of the study. “Our immune system would generate widespread inflammation if attempting this same antiviral strategy. But bats appear uniquely suited to avoiding the threat of immunopathology.” The researchers note that disrupting bat habitat appears to stress the animals and makes them shed even more virus in their saliva, urine and feces that can infect other animals. “Heightened environmental threats to bats may add to the threat of zoonosis,” said Brook, who works with a bat monitoring program funded by DARPA (the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) that is currently underway in Madagascar, Bangladesh, Ghana and Australia. The project, Bat One Health, explores the link between loss of bat habitat and the spillover of bat viruses into other animals and humans. “The bottom line is that bats are potentially special when it comes to hosting viruses,” said Mike Boots, a disease ecologist and UC Berkeley professor of integrative biology. “It is not random that a lot of these viruses are coming from bats. Bats are not even that closely related to us, so we would not expect them to host many human viruses. But this work demonstrates how bat immune systems could drive the virulence that overcomes this.”.... Published in Ecology Epidemiology and Global Health (03 February, 2020): https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.48401

|

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

February 22, 10:13 AM

|

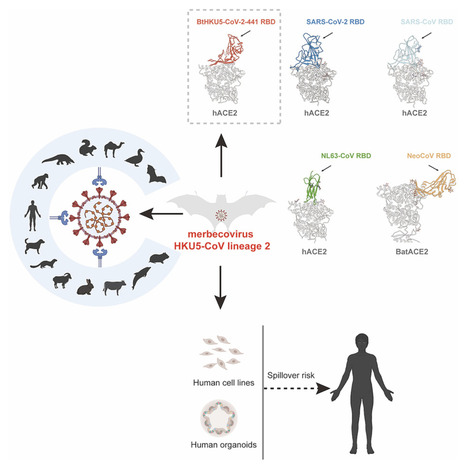

Highlights • A distinct HKU5 coronavirus lineage (HKU5-CoV-2) is discovered in bats • Bat HKU5-CoV-2 uses human ACE2 receptor and ACE2 orthologs from multiple species • Bat HKU5-CoV-2 RBD engages human ACE2 with a distinct binding mode from other CoVs • Bat HKU5-CoV-2 was isolated and infect human-ACE2-expressing cells Summary Merbecoviruses comprise four viral species with remarkable genetic diversity: MERS-related coronavirus, Tylonycterisbat coronavirus HKU4, Pipistrellusbat coronavirus HKU5, and Hedgehog coronavirus 1. However, the potential human spillover risk of animal merbecoviruses remains to be investigated. Here, we reported the discovery of HKU5-CoV lineage 2 (HKU5-CoV-2) in bats that efficiently utilize human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a functional receptor and exhibits a broad host tropism. Cryo-EM analysis of HKU5-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain (RBD) and human ACE2 complex revealed an entirely distinct binding mode compared with other ACE2-utilizing merbecoviruses with RBD footprint largely shared with ACE2-using sarbecoviruses and NL63. Structural and functional analyses indicate that HKU5-CoV-2 has a better adaptation to human ACE2 than lineage 1 HKU5-CoV. Authentic HKU5-CoV-2 infected human ACE2-expressing cell lines and human respiratory and enteric organoids. This study reveals a distinct lineage of HKU5-CoVs in bats that efficiently use human ACE2 and underscores their potential zoonotic risk. Published in Cell (Feb. 18, 2025)

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

July 10, 2024 1:30 PM

|

The angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor is shared by various coronaviruses with distinct receptor-binding domain (RBD) architectures, yet our understanding of these convergent acquisition events remains elusive. Here, we report that two European bat MERS-related coronaviruses (MERSr-CoVs) infecting Pipistrellus nathusii (P.nat), MOW15-22 and PnNL2018B, use ACE2 as their receptor, with narrow ortholog specificity. Cryo-electron microscopy structures of the MOW15-22 RBD-ACE2 complex unveil an unexpected and entirely distinct binding mode, mapping 50Å away from that of any other known ACE2-using coronaviruses. Functional profiling of ACE2 orthologs from 105 mammalian species led to the identification of host tropism determinants, including an ACE2 N432-glycosylation restricting viral recognition, and the design of a soluble P.nat ACE2 mutant with potent viral neutralizing activity. Our findings reveal convergent acquisition of ACE2 usage for merbecoviruses found in European bats, underscoring the extraordinary diversity of ACE2 recognition modes among coronaviruses and the promiscuity of this receptor. Preprint in bioRxiv (July 8, 2024): https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.02.560486

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 29, 2023 11:54 AM

|

Horseshoe bats carry viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2, but they probably can’t spread in people yet. Coronavirus hunters looking for the next pandemic threats have focused on China and southeast Asia, where wild bats carry SARS-CoV-2’s closest known relatives. But a survey of UK bat species suggests that researchers might want to cast a wider net. The trawl turned up new coronaviruses, and some from the same group as SARS-CoV-2. Laboratory studies with safe versions of these viruses suggest that some share key adaptations with SARS-CoV-2 — but are unlikely to spread in humans without further evolution. SARS-CoV-2 belongs to a group of coronaviruses called sarbecoviruses, which circulate in bats. But before the pandemic, efforts to find and characterize these viruses focused on Asia. “Europe and the UK had been totally overlooked,” says Vincent Savolainen, an evolutionary geneticist at Imperial College London who led the study, published on 27 June in Nature Communications. To help plug this gap, Savolainen and his colleagues teamed up with groups involved in bat rehabilitation and conservation to collect a total of 48 faecal samples from bats representing 16 of the 17 species that breed in the United Kingdom. Genetic sequencing turned up nine coronaviruses, including four sarbecoviruses and one related to the coronavirus responsible for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, or MERS, which periodically spills over into camels and humans. Ties that bind — or not To gauge the threat posed by the UK coronaviruses, the researchers created pseudoviruses: non-replicating forms of HIV that are engineered to carry the spike protein that coronaviruses use to infect cells. One sarbecovirus found in a lesser horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus hipposideros) had a spike protein that was able to infect human cells by attaching to a protein called ACE2, the same receptor used by SARS-CoV-2. But the UK sarbecovirus’s version of spike didn’t attach nearly as strongly as SARS-CoV-2’s, and pseudoviruses could infect only human cells with unnaturally high levels of ACE2. This makes it unlikely that the virus could readily infect people and spread, the researchers say. That’s reassuring, but other sarbecoviruses circulating in British bats could be able to bind to human ACE2 more efficiently, says Michael Letko, a molecular virologist at Washington State University in Pullman, who was not involved in the study. A February preprint surveyed UK lesser horseshoe bats and found signs that around half were infected with sarbecoviruses. Further adaptations that help these viruses to infect human cells more efficiently might not be hard to come by, Letko says. “Once the virus has its foot in the door, it’s easier to adapt further.” Tyler Starr, a molecular evolutionary biologist at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, says that sarbecoviruses identified so far in Europe and in Africa probably represent the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the group’s true diversity and geographical distribution. He wouldn’t be surprised if the next sarbecovirus to spill over into humans came from an unprecedented location or branch of the family tree. “The next pandemic threat could very well be in our own backyard,” adds Letko. Cited research published in Nat. Communications (June 27, 2023): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38717-w

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

December 8, 2022 11:15 AM

|

Lloviu cuevavirus (LLOV) was the first identified member of Filoviridae family outside the Ebola and Marburgvirus genera. A massive die-off of Schreibers’ bent-winged bats (Miniopterus schreibersii) in the Iberian Peninsula in 2002 led to its discovery. Studies with recombinant and wild-type LLOV isolates confirmed the susceptibility of human-derived cell lines and primary human macrophages to LLOV infection in vitro. Based on these data, LLOV is now considered as a potential zoonotic virus with unknown pathogenicity to humans and bats. We examined bat samples from Italy for the presence of LLOV in an area outside of the currently known distribution range of the virus. We detected one positive sample from 2020, sequenced the complete coding sequence of the viral genome and established an infectious isolate of the virus. In addition, we performed the first comprehensive evolutionary analysis of the virus, using the Spanish, Hungarian and the Italian sequences. The most important achievement of this article is the establishment of an additional infectious LLOV isolate from a bat sample using the SuBK12-08 cells, demonstrating that this cell line is highly susceptible to LLOV infection. These results further confirms the role of these bats as the host of this virus, possibly throughout their entire geographic range. This is an important result to further understand the role of bats as the natural hosts for zoonotic filoviruses. Preprint available at bioRxiv (Dec. 5, 2022): https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.05.519067

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 24, 2021 11:38 AM

|

Scientist who found archived online files of removed NIH data says recovered information may clarify how coronavirus entered humans. In a world starved for any fresh data to help clarify the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic, a study claiming to have unearthed early sequences of SARS-CoV-2 that were deliberately hidden was bound to ignite a sizzling debate. The unreviewed paper, by evolutionary biologist Jesse Bloom of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, asserts that a team of Chinese researchers sampled viruses from some of the earliest COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China, posted the viral sequences to a widely used U.S. database, and then a few months later had the genetic information removed to “obscure their existence.” To some scientists, the claims reinforce suspicions that China has something to hide about the origins of the pandemic. But critics of the preprint, posted yesterday on bioRxiv, say Bloom’s detective work is much ado about nothing, because the Chinese scientists later published the viral information in a different form, and the recovered sequences add little to what’s known about SARS-CoV-2’s origins. The sequences, Bloom says, do support other evidence that the pandemic did not originate in Wuhan’s Huanan Seafood Market, where SARS-CoV-2 initially came to light. Chinese health officials on 31 December 2019 tied the market to an outbreak of an “unexplained pneumonia,” but a month later, it had become clear that many of the earliest cases had no link to the location. The paper highlights three mutations found in SARS-CoV-2 collected from patients linked to the market that are not in the unearthed sequences of the coronavirus or its closest relative, which researchers from the Wuhan Institute of Virology discovered in bats in 2013. Bloom’s more explosive assertion, that the Chinese researchers deleted data, is bound to intensify the debate about whether the virus originally jumped to humans from an unknown animal or somehow leaked from a laboratory. Bloom says he has no bias toward a particular origin hypothesis for SARS-CoV-2, and he agrees that the viral sequences he highlighted are a small piece of a large unfinished puzzle. “I don't think this bolsters either the lab origin or zoonosis hypothesis,” he says. “I think it provides additional evidence that this virus was probably circulating in Wuhan before December, certainly, and that probably, we have a less than complete picture of the sequences of the early viruses.” Bloom, who studies viral evolution, launched his study after a controversial report on the pandemic’s origin issued in March by a joint commission of Chinese and foreign researchers organized by the World Health Organization (WHO). Bloom helped organize a much discussed letter, co-signed by 17 other scientists, that criticized the WHO report for deeming it “extremely unlikely” that SARS-CoV-2 escaped from a laboratory. In the letter, published on 14 May in Science, the authors argued for “a dispassionate science-based discourse on this difficult but important issue.” The WHO report relied heavily on sequences of SARS-CoV-2 found in COVID-19 patients tied to the market, Bloom notes. “I was just going through and trying to repeat a number of the analyses in the joint WHO-China report,” Bloom says. This led him to a study that listed all SARS-CoV-2 sequences submitted before 31 March 2020 to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA), a database overseen by the National Center for Biotechnology Information, a division of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). But when he checked SRA for one of the listed projects, he couldn’t find its sequences. Googling some of the project’s information, he found another study, led by Ming Wang from Wuhan University’s Renmin Hospital, that was posted as a preprint on 6 March on medRxiv, and later published, on 24 June, in Small, a journal more focused on materials and chemistry than virology. That paper lists some of the earliest Wuhan COVID-19 patients and the specific mutations in their viruses, but doesn’t give the full sequence data. Further internet sleuthing led Bloom to discover that SRA backs up its information in Google’s Cloud platform, and a search there turned up files containing some of the earlier data submissions from Wang's team. The paper in Small makes no mention of any corrections to viral sequences that might explain why they were removed from SRA, which led Bloom to conclude in his preprint that “the trusting structures of science have been abused to obscure sequences relevant to the early spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan.” Bloom asserts that because the deleted sequences lack the three mutations seen in the SARS-CoV-2 from the seafood market, the viruses Wang’s team found more likely represent a progenitor. But the sequence of that bat virus found in 2013 differs from SARS-CoV-2 by about 1100 nucleotides, which means decades must have passed before it evolved into the pandemic coronavirus—and other species may well have been infected with the bat virus before it made the final jump into people. This great difference in sequences, says evolutionary biologist Andrew Rambaut at the University of Edinburgh, means researchers cannot use a few mutations like the ones Bloom highlights to look back in time to see the “roots” of the family tree of SARS-CoV-2 tree. Bloom says he contacted the Chinese researchers to ask why they removed the SRA data, but they did not reply. (Science also received no reply after emailing the lead authors.) NIH issued a statement today saying it removed the sequences at the request of the submitting investigator, who the agency says holds the rights to the data. The scientist “indicated the sequence information had been updated, was being submitted to another database, and wanted the data removed from SRA to avoid version control issues,” NIH said. (Bloom says he cannot find the sequences in any other virology database he knows.) Researchers are sharply divided about the value of Bloom’s resurrection of the SRA data. “This is a creative and rigorous approach to investigating the provenance of SARS-CoV-2,” says Ian Lipkin, a microbiologist at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. “The two take-home points are that the virus was circulating before the outbreak linked to the Wuhan seafood market and that there may have been active suppression of epidemiological and sequence data needed to track its origin.” Leaving aside the meaning of the sequences Bloom found, the demonstration that researchers can potentially find “new” data in the cloud is an exciting advance, adds Sudhir Kumar, who does genomics research at Temple University and has published his own analysis of early SARS-CoV-2 sequences, “Many people feel that there is a lot more Chinese data out there, and they don't have access to it,” he says. Others are underwhelmed. “Jesse is resurfacing info that’s been online for over a year and claiming it proves a cover-up,” says Stephen Goldstein, an evolutionary virologist at the University of Utah. “I don’t understand [his reasoning].” The Small paper is simply a good study that “unfortunately flew below the radar,” he adds. Rambaut notes that the Chinese researchers submitted their Small paper before requesting SRA remove the data. “The idea that the group was trying to hide something is farcical,” Rambaut says. “If they were covering something [up] they surely would have not submitted the paper. … I don't like the insinuations about malfeasance where [Bloom] has zero knowledge of the reasons the authors of the paper had for removing their data.” A member of the WHO origin commission, Marion Koopmans from the Erasmus University Medical Center, notes that its report stresses the need to find more data about the earliest viruses in circulation. “It’s good to see additional data, but I’m not sure what point this makes,” Koopmans says, adding that the preprint’s accusations could harm future collaborations on origin studies with Chinese researchers. “The tone of the intro is in my view rather suggestive and I wish science would stay away from this.” Bloom acknowledges that researchers can piece together the coronavirus sequences from the data found in the Small paper, but he says that’s not the way most in the field conduct evolutionary analyses of SARS-CoV-2. “No one knew about these sequences because the way that people find sequences is to go to the sequence databases and download the sequences and look at them,” Bloom says. Stepping into the divisive discussion of SARS-CoV-2’s origin comes at a price, he acknowledges. “So many people have agendas and preconceived notions on this topic that if you open your mouth on the topic, someone's going to take what you've said to support or reject some particular narrative,” he says. “So the choices are either not to say anything at all, which I don't think is useful or productive, or just to try to draw the conclusions you can and make it as transparent as possible. No matter how much people like [my new study] or don't like it, or agree with the interpretation or disagree with the interpretation, they can at least go download it and repeat it themselves.” Published in Science (June 23, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abk1383 Preprint of the research cited available in bioRxiv (June 22, 2021): https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.18.449051

|

Scooped by

Juan Lama

June 2, 2020 4:25 PM

|

A team of scientists studying the origin of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that has caused the COVID-19 pandemic, found that it was especially well-suited to jump from animals to humans by shapeshifting as it gained the ability to infect human cells. Conducting a genetic analysis, researchers from Duke University, Los Alamos National Laboratory, the University of Texas at El Paso and New York University confirmed that the closest relative of the virus was a coronavirus that infects bats. But that virus's ability to infect humans was gained through exchanging a critical gene fragment from a coronavirus that infects a scaly mammal called a pangolin, which made it possible for the virus to infect humans. The researchers report that this jump from species-to-species was the result of the virus's ability to bind to host cells through alterations in its genetic material. By analogy, it is as if the virus retooled the key that enables it to unlock a host cell's door -- in this case a human cell. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, the "key" is a spike protein found on the surface of the virus. Coronaviruses use this protein to attach to cells and infect them. "Very much like the original SARS that jumped from bats to civets, or MERS that went from bats to dromedary camels, and then to humans, the progenitor of this pandemic coronavirus underwent evolutionary changes in its genetic material that enabled it to eventually infect humans," said Feng Gao, M.D., professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Duke University School of Medicine and corresponding author of the study publishing online May 29 in the journal Science Advances. The researchers found that typical pangolin coronaviruses are too different from SARS-CoV-2 for them to have directly caused the human pandemic. However, they do contain a receptor-binding site -- a part of the spike protein necessary to bind to the cell membrane -- that is important for human infection. This binding site makes it possible to affix to a cell surface protein that is abundant on human respiratory and intestinal epithelial cells, endothelial cell and kidney cells, among others. While the viral ancestor in the bat is the most closely related coronavirus to SARS-CoV-2, its binding site is very different, and on its own cannot efficiently infect human cells. SARS-CoV-2 appears to be a hybrid between bat and pangolin viruses to obtain the "key" necessary receptor-binding site for human infection. Original study published in Science Advances (May 29, 2020): https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abb9153

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...