Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Dr. Stefan Gruenwald

February 1, 2012 12:43 AM

|

Imagine a high-quality 3-D camera that provides more-accurate depth information than the Microsoft Kinect, has a greater range, and works under all lighting conditions — but is so small, cheap and power-efficient that it could be incorporated into a cellphone at very little extra cost. That’s the promise of recent work by Vivek Goyal, the Esther and Harold E. Edgerton Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering, and his group at MIT’s Research Lab of Electronics.

|

Scooped by

Dr. Stefan Gruenwald

February 1, 2012 12:34 AM

|

A frog that can perch on the tip of your pinkie with room to spare has been claimed as the world's smallest vertebrate species, out-tinying a fish that got the title in 2006. But the discoverer of another weensy fish disputes the claim.

|

Scooped by

Dr. Stefan Gruenwald

February 1, 2012 12:00 AM

|

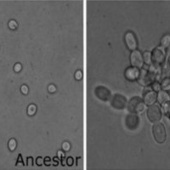

A team from the University of Minnesota, was able to artificially evolve a culture of brewer's yeast into it's multicellular form basically by overfeeding it. The culture was housed in flasks and bathed in an extremely nutrient-rich medium. Once a day, researchers would shake the flasks, then harvested the fast-sinking yeast clumps to start new cultures—the equivalent of natural selection. After just a few weeks, the yeast clumped together and after two months, the clumps had merged into multicelled organisms. What's more, the new creatures showed cell specialization, a juvenile stage, and multicellular offspring. "Multicellularity is the ultimate in cooperation," said evolutionary biologist Michael Travisano, co-author of the study. "Multiple cells make make up an individual that cooperates for the benefit of the whole. Sometimes cells give up their ability to reproduce for the benefit of close kin."

|

Scooped by

Dr. Stefan Gruenwald

February 1, 2012 12:33 AM

|

Natural selection has been wiping out species with subpar adaptive strategies. Among the casualties: dinosaurs, mammoths, Neanderthals, and all manner of megafauna that we’d all love to see first-hand. Alas, mother nature hasn’t been particularly forgiving of species selected against: for four billion years, extinction meant extinction. That is until 2009 when scientists used frozen tissue to successfully clone the Pyrenean ibex, a kind of goat native to the Pyrenees Mountains between Spain and France, making it the first species to become un-extinct. Video collection about cloning: http://tinyurl.com/76dgxqm

|

Scooped by

Dr. Stefan Gruenwald

February 1, 2012 12:21 AM

|

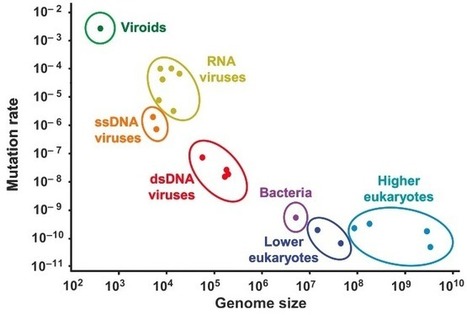

Called hammerhead viroids, their mutation rates are orders of magnitude more rapid than those of viruses, the next-most-primitive organisms, which are orders of magnitude more rapid than lowly bacteria. Thus, the hammerhead viroid blueprint of life is being constantly redrawn. Such an accelerated mutation rate could have been useful four billion years ago, after a few quirky chemicals assembled into ribonucleic acid, or RNA — DNA’s single-stranded forerunner.

|

Scooped by

Dr. Stefan Gruenwald

January 31, 2012 11:48 PM

|

Diabetes is an enormous problem, global in scope, and despite decades of engineering advances, our ability to accurately measure glucose in the human body still remains quite primitive. A new type of sensing system consists of a “tattoo” of nanoparticles designed to detect glucose, injected below the skin. A device similar to a wristwatch would be worn over the tattoo, displaying the patient’s glucose levels.

|

Scooped by

Dr. Stefan Gruenwald

January 31, 2012 11:29 PM

|

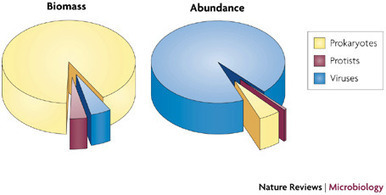

Viruses are by far the most abundant 'lifeforms' in the oceans and are the reservoir of most of the genetic diversity in the sea. The estimated 10^30 viruses in the ocean, if stretched end to end, would span farther than the nearest 60 galaxies. Every second, approximately 10^23 viral infections occur in the ocean. These infections are a major source of mortality, and cause disease in a range of organisms, from shrimp to whales. As a result, viruses influence the composition of marine communities and are a major force behind biogeochemical cycles. Each infection has the potential to introduce new genetic information into an organism or progeny virus, thereby driving the evolution of both host and viral assemblages. Probing this vast reservoir of genetic and biological diversity continues to yield exciting discoveries. Viruses can be found in every environment on the Earth, but their importance is perhaps most evident in the oceans, where they are known to be the reservoir of most of the genetic diversity. Viruses kill approximately 20% of the oceanic microbial biomass daily, which has a significant impact on nutrient and energy cycles. This Review highlights areas in which marine virology is advancing quickly or seems to be poised for paradigm-shifting discoveries. Developing the necessary techniques to obtain accurate and reproducible estimates of the distribution and abundance of marine viruses has been a challenge for researchers. Sub-populations of both viruses and host cells can now be discriminated using flow cytometry. Viral abundance generally co-varies with prokaryotic abundance and productivity, but marked differences in this relationship have been reported in different marine environments. Quantifying the effects of viruses on marine prokaryotic and eukaryotic heterotrophic and autotrophic communities is also a challenging area, and remains one of the biggest obstacles to incorporating viral-mediated processes into global models of nutrient and energy cycling. Our knowledge of the diversity of viruses in marine environments has increased greatly with the development of metagenomic approaches. The interactions between viruses and the organisms they infect ultimately control the genetic diversity of viruses and potentially influence the composition of microbial communities. However, the experimental evidence that supports the hypothesis that viruses regulate microbial diversity in nature is ambiguous. This is perhaps not surprising as the effects of viruses on their host cells depend on transient associations, which might lead us to expect that the influences of viruses on host populations will also be spatially and temporally variable. Viruses/bacteria video collection: http://tinyurl.com/7plkwe3

|

|

Scooped by

Dr. Stefan Gruenwald

February 1, 2012 12:41 AM

|

The former Lucasian professor of mathematics and theoretical physics at the University of Cambridge is widely regarded as one of the most brilliant theoretical physicists since Einstein. He has 12 honorary degrees, a CBE and in 2009 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the US. Now aged 70, he has long defied and baffled medical experts who predicted he had just months to live in 1963 when he was diagnosed with Motor Neurone Disease (MND). Key points of Dr. Hawking's life: - Born in Oxford on 8 Jan 1942, brought up in St Albans. Father a research biologist, mother a radical free-thinker

- Labelled a swot at public school, he liked horse riding, rowing, classical music and debating

- A Brief History of Time - the 1988 layman's guide to cosmology - has sold 10 million copies worldwide

- Discovered "Hawking radiation", where black holes leak energy and fade to nothing, and "theory of everything" suggesting universe evolves according to well-defined laws

- Popular ambassador for science, he lent his synthesized voice to various recordings and appeared in BBC comedy Red Dwarf, The Simpsons and Star Trek

- In 2001, he claimed mankind could be wiped out by a genetically engineered "doomsday" virus

- In an interview with the New Scientist ahead of his 70th birthday, he said he spent most of the day thinking about women, who he says are "a complete mystery"

|

Scooped by

Dr. Stefan Gruenwald

February 1, 2012 12:23 AM

|

Volunteers can go to the Planethunters website to see time-lapsed images of 150,000 stars, taken by the Kepler space telescope. They will be advised on the signs that indicate the presence of a planet and how to alert experts if they spot them. "We know that people will find planets that are missed by the computer," said Chris Lintott from Oxford University.

|

Scooped by

Dr. Stefan Gruenwald

January 31, 2012 11:58 PM

|

An ultra-low-cost computer for use in teaching computer programming to children has been developed by The Raspberry Pi Foundation, a UK registered charity. The first version is about the size of a USB key, and is designed to plug into a TV or be combined with a touch screen for a low cost tablet. The expected price is $25 for a fully configured system.

|

Scooped by

Dr. Stefan Gruenwald

January 31, 2012 11:56 PM

|

What will the future of medicine bring? Tiny body monitors, large patient databases and the end of illness. Today, we mostly wait for the body to break before we treat it. In the near future, we will be able to monitor and adjust our health in real time with the help of smartphones, wearable gadgets and many other devices.

|

Scooped by

Dr. Stefan Gruenwald

January 31, 2012 11:49 PM

|

The New England Journal of Medicine marks its 200th anniversary this year with a timeline celebrating the scientific advances first described in its pages: the stethoscope (1816), the use of ether for anesthesia (1846), and disinfecting hands and instruments before surgery (1867), among others. For centuries, this is how science has operated — through research done in private, then submitted to science and medical journals to be reviewed by peers and published for the benefit of other researchers and the public at large. But to many scientists, the longevity of that process is nothing to celebrate. The system is hidebound, expensive and elitist, they say. Peer review can take months, journal subscriptions can be prohibitively costly, and a handful of gatekeepers limit the flow of information. It is an ideal system for sharing knowledge, said the quantum physicist Michael Nielsen, only “if you’re stuck with 17th-century technology.” Dr. Nielsen and other advocates for “open science” say science can accomplish much more, much faster, in an environment of friction-free collaboration over the Internet. And despite a host of obstacles, including the skepticism of many established scientists, their ideas are gaining traction. Open-access archives and journals like arXiv and the Public Library of Science (PLoS) have sprung up in recent years. GalaxyZoo, a citizen-science site, has classified millions of objects in space, discovering characteristics that have led to a raft of scientific papers. On the collaborative blog MathOverflow, mathematicians earn reputation points for contributing to solutions; in another math experiment dubbed the Polymath Project, mathematicians commenting on the Fields medalistTimothy Gower’s blog in 2009 found a new proof for a particularly complicated theorem in just six weeks. And a social networking site called ResearchGate — where scientists can answer one another’s questions, share papers and find collaborators — is rapidly gaining popularity. Editors of traditional journals say open science sounds good, in theory. In practice, “the scientific community itself is quite conservative,” said Maxine Clarke, executive editor of the commercial journal Nature, who added that the traditional published paper is still viewed as “a unit to award grants or assess jobs and tenure.” Dr. Nielsen, 38, who left a successful science career to write “Reinventing Discovery: The New Era of Networked Science,” agreed that scientists have been “very inhibited and slow to adopt a lot of online tools.” But he added that open science was coalescing into “a bit of a movement.” Video collection about discussions in regards to "Open Science": http://tinyurl.com/7xezgel

|

Scooped by

Dr. Stefan Gruenwald

January 31, 2012 11:30 PM

|

The Northern Lights have lit up the skies above Scotland, Canada and Norway after the biggest solar storm in more than six years bombarded Earth with radiation. Solar storms video collection: http://tinyurl.com/7pamtq3

|

Scooped by

Dr. Stefan Gruenwald

January 31, 2012 11:22 PM

|

Historical list of leap seconds since 1972 Unlike the better-known leap year, which adds a day to February in a familiar four-year cycle (with a few well-defined exceptions), the leap second is tacked on once every few years to synchronize atomic clocks — the world’s scientific timekeepers — with Earth’s rotational cycle, which, sadly, does not run quite like clockwork. The United States is the primary proponent for doing away with the leap second, arguing that the sporadic adjustments, if botched or overlooked, could lead to major foul-ups if electronic systems that depend on the precise time — including computer and cellphone networks, air traffic control and financial trading markets — do not agree on the time. Since the 1950s, the world has run on two sets of clocks. One is the ticking of atomic clocks, defined by the precise frequency that electrons jump around in atoms. The other is based on the traditional notion of a spinning Earth. If the leap second is stamped out, the astronomical definition of time will diverge from what is dictated by the atomic clocks, about a couple of thousandths of a second a day, growing to a minute over the course of a century, and someday — thousands of years from now — noon will strike at sunrise instead of when the sun is overhead. The problem is a distinctly modern one. Only a few centuries ago, people set their watches by the clock in the town square, and the time in each town was different from the next. That mattered little, since there was no need or ability to communicate with anyone elsewhere in the world. Railroads changed the situation, creating the need to set cross-country schedules. This in turn led to the creation of time zones, synchronizing time across large swaths. But the length of a day and a second remained tied to the rotation of Earth. In 1967, the nations of the world changed things around, creating a new definition of a second based on atomic clocks and pegged to the length of an astronomical day in 1900. But Earth, like any spinning top, has slowed down since 1900, and the time between sunrise and sunset has grown longer. Atomic clocks now run slightly ahead of what is defined in the sky, and, starting in 1972, leap seconds have been added to keep the two sets of clocks synchronized. A panel of experts at the International Telecommunication Union, an arm of the United Nations, began discussions eight years ago, but could not come to a consensus to keep or get rid of them. The United States and Britain have been butting heads over the issue over most of that time. “What it decided was to give the baby to the higher levels,” said François Rancy, director of the union’s radio communication bureau. Discussions are continuing between the United States and Britain, and Mr. Rancy said he hoped the two could finally come to a consensus in the hours before that agenda item is reached. But if necessary, the proposal to eliminate leap seconds would be put to a vote of the delegates. In a poll conducted by the union last year, only 16 nations expressed an opinion. Thirteen would abolish leap seconds. Three wanted to keep them. If approved, the recommendation would still have to be ratified by a larger meeting next month. Regardless, there will be one extra second to enjoy this summer. The change would not take effect until 2018.

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...