Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

December 10, 2018 6:09 PM

|

The Fourth National Climate Assessment focuses on human welfare, societal, and environmental elements of climate change. It lays out the devastating effects on the economy, health, environment, and wildfires. Within the 1,656-page document wildfires are covered extensively. The scientists conclude that by the middle of this century, the annual area burned in the western United States could increase 2–6 times from the present, depending on the geographic area, ecosystem, and local climate. The area burned by lightning-ignited wildfires could increase by 30% by 2060. In the Southeast rising temperatures and increases in the duration and intensity of drought are expected to increase wildfire occurrence and also reduce the effectiveness of prescribed fire. Intra-annual droughts, like the one in 2016, are expected to become more frequent in the future. Thus, drought and greater fire activity are expected to continue to transform forest ecosystems in the region. In the Southwest, recent wildfires have made California ecosystems and Southwest forests net carbon emitters (they are releasing more carbon to the atmosphere than they are storing). With continued greenhouse gas emissions, models project more wildfire across the area. Under higher emissions, fire frequency could increase 25%, and the frequency of very large fires (greater than 5,000 hectares) could triple. The Northwest is likely to continue to warm during all seasons under all future scenarios, although the rate of warming depends on current and future emissions. The warming trend is projected to be accentuated in certain mountain areas in late winter and spring, further exacerbating snowpack loss and increasing the risk for insect infestations and wildfires. In central Idaho and eastern Oregon and Washington, vast mountain areas have already been transformed by mountain pine beetle infestations, wildfires, or both, but the western Cascades and coastal mountain ranges have less experience with these growing threats. Forests in the interior Northwest are changing rapidly because of increasing wildfire and insect and disease damage, attributed largely to a changing climate. These changes are expected to increase as temperatures increase and as summer droughts deepen.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

August 7, 2018 10:21 AM

|

In his first remarks on the vast California wildfires that have killed at least seven people and forced thousands to flee, President Trump blamed the blazes on the state’s environmental policies and inaccurately claimed that water that could be used to fight the fires was “foolishly being diverted into the Pacific Ocean.” State officials and firefighting experts dismissed the president’s comments, which he posted on Twitter. “We have plenty of water to fight these wildfires, but let’s be clear: It’s our changing climate that is leading to more severe and destructive fires,” said Daniel Berlant, assistant deputy director of Cal Fire, the state’s fire agency. He and others said that Mr. Trump appeared to be referring to a perennial and unrelated water dispute in California between farmers and environmentalists. Farmers have long argued for more water to be allocated to irrigating crops, while environmentalists counter that the state’s rivers would suffer and fish stocks would die. The president first addressed the fires late Sunday, writing on Twitter, “California wildfires are being magnified & made so much worse by the bad environmental laws which aren’t allowing massive amount of readily available water to be properly utilized.” He also referred to a debate in forest management about the effectiveness of removing trees and vegetation as a fire control method.

***

William Stewart, a forestry specialist at the University of California, Berkeley, said he believed Mr. Trump was referring to the battle over allocating water to irrigation versus providing river habitat for fish. That debate has no bearing on the availability of water for firefighting. Helicopters lower buckets into lakes and ponds to collect water that is then used to douse wildfires, and there is no shortage of water to do so, Cal Fire officials said.

***

Mr. Trump raised another issue when he wrote that officials “must also tree clear to stop fire spreading.” Scientists and forest experts said the president was referring to a valid and continuing debate. The timber industry has argued that “thinning” forests — removing certain trees to improve the health of the remaining ones and diminish the plants and underbrush that fuel fires — reduces the risk of wildfires. Republicans in Congress have sought to loosen environmental restrictions to allow more thinning. Democrats and environmentalists argue the practice will open the door to expanded commercial logging and threaten wildlife.

***

The president in the past has dismissed climate change as a hoax and his top cabinet officials have questioned the established science that rising global temperatures are caused by human activity. Michael F. Wehner, a senior staff scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, said it was not possible to quantify precisely the likelihood that climate change is having an impact on forest fires, as can now be done with other extreme-weather events such as heat waves. And, he said, it’s not easy to weigh how much of the problem can be laid at the feet of forest-management practices. *** California fire officials on Monday said the Carr Fire in Shasta County had ravaged more than 160,000 acres while the Mendocino Complex fires grew overnight and had charred more than 273,000 acres across Mendocino, Lake and Colusa counties.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

February 13, 2018 8:13 AM

|

In Vermont and across New England and northern New York, many economically and culturally important tree species and forest communities will face increasing threats under warmer and more variable conditions, according to a new assessment of the vulnerability of the region’s forests to climate change led by the USDA Forest Service. A team that included Forest Service scientists, National Forest managers, state natural resource managers, other federal agencies, university researchers, and conservation organizations contributed to the report, “New England and Northern New York Forest Ecosystem Vulnerability Assessment and Synthesis: A Report from the New England Climate Change Response Framework Project.” The report was published this week by the USDA Forest Service’s Northern Research Station and is available at https://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/55635.

***

Key findings — Over decades, conditions will deteriorate for iconic tree species in the region such as red spruce, sugar maple, paper birch, northern white cedar, and balsam fir. Habitat conditions will become more favorable for species such as black cherry, yellow-poplar, and several oak and hickory species, all trees that are currently found south of New England. — Precipitation is projected to increase in winter and spring across a range of climate scenarios. Intense precipitation events are expected to continue to become more frequent. — Winters will continue to become shorter and milder. Snowfall is projected to continue to decline across the assessment area, with more winter precipitation falling as rain.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

October 24, 2016 4:49 PM

|

The New Zealand Superannuation Fund on Wednesday unveiled a climate change strategy aimed at improving investment returns while making its NZ$31.4 billion ($22.2 billion) portfolio more resilient to long-term, climate-related risks.

CEO Adrian Orr called the strategy a “significant and fundamental shift” for the Auckland-based fund, “consistent with our mandate to maximize returns without undue risk,” according to a news release.

While NZ Super has taken climate-related factors into account for years, in areas such as engagement with companies it invests in, the policy announced Wednesday amounts to a broad “intensification” of the fund's approach, said spokeswoman Catherine Etheredge.

NZ Super's four-part strategy commits the fund to:

- significantly reduce its exposure to fossil fuels and carbon emissions over time;

- incorporate climate change into investment analysis and decisions;

- manage climate risk through active engagement with companies; and

- actively seek investment opportunities in areas such as renewable energy.

The new approach calls for NZ Super to report its carbon footprint annually from 2017, with the goal of achieving substantial cuts in both carbon emissions and fossil fuel reserves over time.

The news release said the fund will pursue that goal through “ongoing engagement with companies, building carbon measures into (the fund's) investment model, targeted divestment of high-risk companies and reduction of other relevant portfolio exposures.”

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

May 13, 2016 11:37 AM

|

Hurricanes hitting the Southeast coast can supercharge the region’s forests, spurring them to store more than 100 times the carbon released annually by all vehicles in the U.S., Duke University researchers have found.

Rainfall associated with hurricanes acts as fuel for photosynthesis, drastically increasing trees’ carbon absorption rates, according to a recent study published in the journal Biogeosciences. Forests hit by tropical cyclones account for 9 percent of the warm season forest carbon sequestration in the region, the study said.

The researchers studied the Southeast coast because it is the target of more hurricanes and tropical storms than any other part of the U.S. It also harbors massive forests that absorb large amounts of carbon.

Scientists are unsure how a changing climate will affect the intensity and frequency of hurricanes, but studies suggest that the Southeast coast could see more tropical storms and hurricanes in a warming world along with more frequent drought due to warmer temperatures.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

April 8, 2016 12:19 PM

|

The bend-don’t-break adaptability of trees extends to handling climate change, according to a new study that says forests may be able to deal with hotter temperatures and contribute less carbon dioxide to the atmosphere than scientists previously thought. In addition to taking in carbon dioxide during photosynthesis, plants also release it through a process called respiration. Globally, plant respiration contributes six times as much carbon dioxide to the atmosphere as fossil fuel emissions, much of which is reabsorbed by plants, the oceans and other elements of nature. Until now, most scientists have thought that a warming planet would cause plants to release more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, which in turn would cause more warming. But in a study published Wednesday in Nature, scientists showed that plants were able to adapt their respiration to increases in temperature over long periods of time, releasing only 5 percent more carbon dioxide than they did under normal conditions.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

March 14, 2016 12:33 PM

|

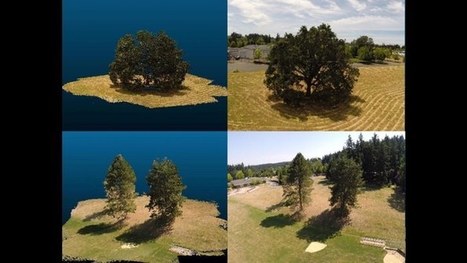

Considering that it takes hundreds of years for forests to grow, it can be difficult to assess how they'll be affected by climate change in the long term. To address that problem, researchers at Washington State University have created the world's first computer simulation capable of growing realistic forests, using the model to predict how things like frequent wildfires or drought might impact forests across North America.

The new computer simulation allows scientists to grow a virtual forest over the period of a few weeks. Known as LES (after the Russian word for forest), the system simulates the growth of 100 x 100 m (330 x 330 ft) areas of vegetation, that are then scaled up to simulate entire forests. It's more complex than any previous systems, simulating both canopy structures and intricate root systems for each tree. Each leaf competes for sunlight, while beneath the virtual earth, the organisms' roots compete for water resources.

In order to ensure that the model accurately represents real-life forests, the researchers turned to the US Department of Agriculture's Forest Inventory and Analysis program, as well as other forestry databases. They also worked with the US Forest Service to fly drones over and around forests, imaging them to gather further information and develop 3D models, allowing for more accurate vegetation and tree distribution.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

January 12, 2016 7:45 AM

|

Liberal news outlets are reporting 2015 is a record year for wildfires in the U.S. and that that record was likely driven by man-made global warming. That’s completely false.

The U.S. Forest Service reports fires burned 10.1 million acres of private, state and federal lands in 2015 — a record number of acres, according to the agency. Forest Service officials told liberal media outlets they had to borrow money three times to put out fires, and more than half the agency’s budget went to firefighting in 2015.

But 10.1 million acres is not a record amount for wildfires. In fact, it’s not even close to the worst wildfire season in U.S. history. The number of acres burned last year is only about one-fifth the acreage burned in 1930 and 1931 when more than 50 million acres burned.

There’s even evidence wildfires burned upwards of 140 million acres in pre-industrial times. Federal data shows effective management strategies like prescribed burns can reduce wildfire risks and improve land health.

What’s most interesting is the years with the worst wildfires occurred when carbon dioxide emissions were only a quarter of what they are today. This is important because scientists claim CO2 and other greenhouse gases are heating up the planet and driving more wildfires.

Data going back nearly 90 years seems to indicate a negative correlation between CO2 and wildfires, but that changes when data is “cherry-picked” to only include data going back to the 1960s. A correlation between rising CO2 and wildfires magically appears when data only starts in the 60s.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

September 1, 2015 1:20 PM

|

Deforestation will cost the Earth an India-sized patch of forest by mid-century––a crippling blow to the climate––but carbon pricing could halve the loss, according to a new study.

A comprehensive new analysis of satellite imagery and land use practices across 101 countries shows that one-seventh of the world's tropical forests will be lost over the next 35 years, an area equal to roughly one-third of the United States.

Such a tremendous loss of forests and the burning of the carbon they contain would hasten global warming significantly. The loss, however, could be cut nearly in half by placing a price on carbon that pays landowners to keep their forests intact.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

June 12, 2015 11:53 AM

|

A new report from Mercer modelling the potential impact of climate change on investments, has found investors cannot ignore the implications for investment returns. ***

The investment modelling in Mercer’s report estimates the potential impact of climate change on returns for portfolios, asset classes and industry sectors between 2015 and 2050, based on four climate change scenarios and four climate risk factors.

***

The investment modelling supports the following key findings: (1) Climate change will give rise to investment winners and losers ***

(2) The biggest risk is at the industry level

Differentiation between winners and losers is most apparent at the industry level – For example, depending on the climate scenario which plays out, the average annual returns from the coal sub-sector could fall by anywhere between 18% and 74% over the next 35 years... *** Conversely, the renewables sub-sector could see average annual returns increase by between 6% and 54% over a 35 year time horizon (or between 4% and 97% over a 10-year period) depending on the climate scenario.

(3) Asset-class return impacts will be material, but vary widely by climate change scenario

***

A 2°C scenario could see return benefits for emerging market equities, infrastructure, real estate, timber and agriculture. A 4°C scenario could negatively impact emerging market equities, real estate, timber and agriculture.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

February 17, 2015 6:08 PM

|

In a paper which appears in Nature Geoscience this month, a group of ecologists demonstrated that these fires scorching Earth's northernmost forests can, paradoxically, have a chilling effect on our climate. A smoldering blaze kicks up plumes of heat-trapping soot, which eventually settle back to the ground, hastening snowmelt. Combustion also releases carbon dioxide, our planet's most important heat-trapping greenhouse gas. These effects, like the heat from the blaze itself, tend to warm the planet up.

But as wildfires eat through forests, they also expose the ground, and in the far north, that means uncovering snow and ice. The dark, leafy landscape becomes a bright, reflective one. In climate science lingo, reflectivity is called albedo, and it's a critically important factor for determining how much of the sun's energy our planet absorbs. By increasing a landscape's albedo, fires can reflect more of the sun's radiation back to space and cool the climate.

Trees, in other words, affect our climate almost as much as humans do.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

October 2, 2014 8:15 PM

|

Forest ecosystems across the Northwoods will face direct and indirect impacts from a changing climate over the 21st century. This assessment evaluates the vulnerability of forest ecosystems in the Laurentian Mixed Forest Province of northern Wisconsin and western Upper Michigan under a range of future climates. Information on current forest conditions, observed climate trends, projected climate changes, and impacts to forest ecosystems was considered in order to assess vulnerability to climate change. Upland spruce-fir, lowland conifers, aspen-birch, lowland-riparian hardwoods, and red pine forests were determined to be the most vulnerable ecosystems. White pine and oak forests were perceived as less vulnerable to projected changes in climate. These projected changes in climate and the associated impacts and vulnerabilities will have important implications for economically valuable timber species, forest-dependent wildlife and plants, recreation, and long-term natural resource planning.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

June 20, 2014 2:06 PM

|

Minnesota's northern forests are expected to look vastly different a century from now -- with fewer spruce, tamarack and fir trees and more maple, oak and basswood -- due to a warming climate.

That's the finding of a major new study headed by the U.S. Forest Service Northern Research Station and released Thursday.

The study took an in-depth look at some 23.5 million acres of forest across northern Minnesota and describes both the effects of climate change that have already been observed as well as projections on what continued warming is expected to do.

The findings, which echo what many scientists already have said, are that trees already at the southern end of their range will do poorly -- including balsam fir, aspen, white spruce and tamarack. Tree species at the northern edge of their range will do better -- including basswood, black cherry, white pine, red maple, sugar maple and white oak.

According to the report's findings, significant changes in Minnesota's climate have been documented over the past century. On average, northern Minnesota forests are seeing less snowfall but more severe winter storms. Meanwhile, minimum and maximum temperatures have been increasing across all seasons, with winter temperatures rising the most. Rainfall in the spring and fall has increased, with more of that precipitation occurring in downpours of 3 inches or more.

***

The 240-page report predicts: - Temperature increases will lead to longer growing seasons in northern Minnesota forests.

- The number of heavy precipitation events will continue to increase in northern Minnesota, and impacts from flooding and soil erosion may also become more damaging.

- Forests may experience more drought stress during the growing season, as well as increased risk of forest fires and an increase in forest pests and invasive species.

|

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

October 16, 2018 9:22 AM

|

Warmer temperatures brought on by climate change will lead to drier soils and reduce tree photosynthesis and growth in forests later this century, according to a new University of Minnesota study published in the journal Nature. That important conclusion comes as scientists have speculated the opposite: that a warming climate might speed up a forests' photosynthesis and facilitate growth in cold-weather climates found in North America, Europe and Asia. "These results have important implications for the future," said Peter Reich, a professor of forest resources in the College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences and the study's lead author. "Typical dry spells already occur frequently enough to erase most of the potential benefits to tree growth of warmer summer temperatures. In a warmer future, the extra evaporation from warmer plants and soils will make those dry spells drier, further suppressing photosynthesis." Cool summers slow the growth of forests in cold places. That's why scientists had hypothesized that warmer climatological conditions might help increase a forest's growth rate in the future. In their study, University of Minnesota researchers looked at more than 2,000 young trees from 11 different species—including birch, maple, oak, pine and spruce—growing in 48 plots in two forests in northern Minnesota. During the three-year study, researchers increased temperatures at the test plots—without use of chambers of any kind—by 3.4 degrees Celsius (6 degrees Fahrenheit), an increase that might happen in Minnesota by the end of the 21st century. During the course of the study, researchers routinely measured photosynthesis at the plots to see how fast leaves were taking carbon dioxide out of the air to make sugars for the trees. Researchers found that:when soils were moist, photosynthesis was higher in plants growing at warmer than at ambient temperatures;in moderately to severely dry soils, which occurred during two-thirds of the growing season, warmer temperatures reduced photosynthesis;as a result, photosynthesis was reduced—on average—by the experimental climate warming. "These results show that low soil moisture will slow down or eliminate any potential benefits of climate warming on tree photosynthesis even in moist, cold climates like Minnesota, Canada and Siberia," said Reich.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

February 26, 2018 4:05 PM

|

Beech trees are dominating the woodlands of the northeastern United States as the climate changes, and that could be bad news for the forests and people who work in them, according to a group of scientists.

The scientists say the move toward beech-heavy forests is associated with higher temperatures and precipitation. They say their 30-year study, published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Applied Ecology, is one of the first to look at such broad changes over a long time period in the northeastern U.S. and southeastern Canada.

The changes could have major negative ramifications for forest ecosystems and industries that rely on them, said Dr. Aaron Weiskittel, a University of Maine associate professor of forest biometrics and modeling and one of the authors.

Beech, often used for firewood, is of much less commercial value than some species of birch and maple trees that can be used to make furniture and flooring.

"There's no easy answer to this one. It has a lot of people scratching their heads," Weiskittel said. "Future conditions seem to be favoring the beech, and managers are going to have to find a good solution to fix it."

The authors of the study, who are from the University of Maine and Purdue University, used U.S. Forest Service data from 1983 to 2014 from the states of Maine, New Hampshire, New York and Vermont to track trends in forest composition. They found that abundance of American beech increased substantially, while species including sugar maple, red maple and birch all decreased.

That's a problem not only because of beech's lower value, but because of the spread of beech bark disease, which causes the trees to die young and be replaced by newer trees that succumb to the same disease.

The authors found that the rise of beech and the decline of other species is associated with "higher temperature and precipitation" in the forests. The dominance of beech was also especially notable in some key tourist areas — the White Mountains of New Hampshire, the Adirondack Mountains of New York and the Green Mountains of Vermont.

And beech has the possibility to grow even more because it's not a favorite food of deer, which will eat more seedlings of other trees, Weiskittel said.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

June 19, 2017 12:15 PM

|

*** However, there are far less emotional—and far more realistic and shrewd—reasons to remain level-headed should the US formally withdraw from the Paris Climate Accord. A number of economists and analysts believe that President Trump’s decision essentially changes nothing because COP21 commitments are non-binding. *** Key reasons why President Trump’s decision will have no measurable impact include: - The official global target of a 2°C temperature rise is “utterly inadequate,” according to a lead author on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Petra Tschakert from Pennsylvania State University and a coordinating lead author of the IPCC's Fifth Assessment Report noted that, "The consensus that transpired during this session was that a 2°C danger level seemed utterly inadequate given the already observed impacts on ecosystems, food, livelihoods, and sustainable development.”

*** - Fundamental economics and rapidly emerging technologies, rather than regulation, are driving the US shift away from fossil fuels and toward renewable energy sources. Besides the improving economics of renewable energy sources, coal is coming under pressure from competitive natural gas prices.

*** - "The increasingly favorable economics of renewables are more important than the presidential election’s impact on the industry, in our view,” says Stephen Byrd, a senior analyst with Morgan Stanley. “Wind and solar are price-competitive in many parts of the US. It’s the economics and not the politics that’s driving the use of renewables.”

*** - The process of a US withdrawal from COP21 is complex; it’s not as if the US can immediately scrap its current responsibilities as a member nation of the pact—even if they are non-binding in this case. A country that is part of the Accord can withdraw only four years after giving notice of its intent to do so.

*** Josiah Neely astutely notes that, “[The] United States has over the past decade reduced its greenhouse-gas emissions by more than almost any other country. It did this despite the fact that it had not joined the Kyoto Protocol, a previous international agreement meant to fight climate change. Instead of imposing costly measures to reduce emissions, the United States succeeded because of new technologies that were both cheaper and cleaner than existing sources.” While such nebulous international agreements as COP21 and the Kyoto Protocol do have the potential to galvanize support, the free market—not government—will ultimately develop and implement scalable renewable solutions that will benefit both the environment and humanity in the coming decades.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

May 20, 2016 10:50 AM

|

Drought could render the U.S. Northeast’s mixed forests unsustainable after 2050 while Washington’s Cascade Mountains may require tropical and subtropical forest species, according to researchers using a new type of mathematical model at Washington State University.

***

WSU Vancouver mathematicians Jean Liénard and Nikolay Strigul, and ecologist John Harrison, predict the Pacific Northwest’s climate may be warmer and wetter, requiring the establishment of forest types seen in places like southeastern China, southern Brazil or sub-Saharan Africa. Predicted forest types in the U.S. for projected climates determined by the WSU tolerance model.

In the northeastern U.S., the model projects forests of maple/beech/birch, spruce/fir and white/red/jack pine combinations will be ill-suited to withstand predicted drought conditions by the latter half of the 21st century. Other forested areas that were identified as being at risk from drought included the northern Great Plains and the higher elevations of the Rocky Mountains. Meanwhile, low altitude areas of Texas may eventually host tropical dry forests similar to regions of eastern Mexico. Moist, deciduous forests found in locations like Cuba could one day thrive along the U.S. Gulf Coast. “Until now, our ability to predict exactly how and where forest characteristics and distributions are likely to be altered as a result of climate change has been rather limited,” said Liénard, a postdoctoral researcher and the paper’s first author. “With our model, it is possible to identify which forests are at the greatest risk from future environmental stressors. Forest managers and private landowners could then take steps like planting drought tolerant seedlings and saplings to prepare.”

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

April 18, 2016 10:46 AM

|

University of Victoria scientists say they have some good news about global warming and its impact on British Columbia’s forests, especially about the environment’s recovery from the devastating mountain pine beetle outbreak more than a decade ago.

A group of scientists at the university’s Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions have discovered that global warming is producing larger trees and faster-growing forests.

The findings, published in the peer-reviewed scientific journal American Geophysical Union, conclude global warming is making BC forests grow faster and the trees in those forests are able to take in more carbon dioxide, the gas associated with the globe’s steadily climbing temperatures.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

April 4, 2016 10:24 AM

|

Pension funds will be the subject to a climate disclosure framework being drawn up by a group convened by the Financial Stability Board (FSB).

The Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), chaired by US businessman Michael Bloomberg, also said it would look to enhance the disclosure framework for unlisted asset classes, including real estate and infrastructure.

Initially convened to design a consistent disclosure framework for listed companies to benefit institutional investors, the TCFD has now said it will also look at “effective” reporting by the financial sector.

Publishing its first report since being announced at the UN Climate Change Conference in Paris last year, the TCFD noted the “growing demand for decision-useful climate-related information” by financial market participants, which it said had led to a proliferation of different disclosure frameworks.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

February 2, 2016 11:52 AM

|

In August last year, France became the first country to introduce mandatory climate change-related reporting for institutional investors.

The relevant law has been hailed as “groundbreaking”, with potentially far-reaching implications.

Many investors, in the meantime, have their work cut out for them.

The reporting obligations are set out under Article 173 of France’s law on “energy transition for green growth”, with an implementing decree setting out the requirements in greater detail.

Effective since the beginning of January, the decree applies to a wide range of investors, including asset managers, insurance companies, Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations and pension and social security funds.

They are being required to report not only on how they integrate environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors in general into their investment policies – and, where applicable, risk management – but also specifically on how climate change considerations are incorporated.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

September 14, 2015 10:12 AM

|

If the air feels just a bit fresher, it may be because the trees are making a comeback. Despite a lot of bad news on climate, our planet has become measurably greener, as seen from space. And that points to a way out of the climate crisis.

A group of scholars at Australian, Chinese, Dutch and Saudi Arabian universities recently published, in the journal Nature Climate Change, a 20-year study measuring the precise quantity of the Earth’s “terrestrial biomass” – that is, the total mass of living organisms, most of which are plants. They used two decades of microwave satellite readings (which are an accurate way to measure biological material) to determine how the world’s stock of living things has changed over time.

***

What the study found was, in the initial years, predictably depressing: Between 1993 and 2002, the world’s stock of plants declined – in large part because of large-scale deforestation in the tropical rain forests of Brazil and Indonesia.

But then, between 2003 and 2012 (the last year they analyzed), something surprising happened: The trees started growing back. Their results showed that deforestation in Brazil and Indonesia slowed sharply, while better growing conditions in the savannahs of northern Australia and southern Africa added mass, and – most dramatically – the vast forests of China and Russia grew back at a considerable pace. *** What is most significant is not that the world’s forests are growing back, but the reasons why. Almost all of the regreening of the post-2003 years was caused, whether through explicit policy or happy accident, by countries increasing their level of urbanization, their proportion of commercial agriculture or their rate of economic growth – all of which created the conditions for a more carbon-friendly ecology.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

June 22, 2015 12:04 PM

|

The Department of Forests, Parks and Recreation released a guidebook last month on adapting forests for climate changes.

The guidebook, titled “Creating and Maintaining Resilient Forests in Vermont: Adapting Forests to Climate Change,” was written with the purpose of supplementing current forest management planning and practices with forest-adaptation strategies that are more relevant to the current climate change trends and projections.

Immediate risks to the forests due to climate change are increases in chance of fire, changes in freeze cycles that could disrupt regular cone production among many others, according to the guidebook.

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

March 23, 2015 10:15 AM

|

The Amazon has long been seen as a life preserver of sorts in the global warming fight, its lush forest storing billions of tons of carbon.

But now a paper published in Nature Wednesday says that the Amazon is losing its capacity to serve as a carbon sink. In a 30-year study of the South American tropical forest, an international team found that the Amazon has gone from storing 2 billion tons of carbon dioxide each year in the 1990s to half that now.

***

"Climate change models that include vegetation responses assume that as long as carbon dioxide levels keep increasing, then the Amazon will continue to accumulate carbon," he said. "Our study shows that this may not be the case and that tree mortality processes are critical in this system."

William R. L. Anderegg, a NOAA Climate & Global Change Postdoctoral Fellow at the Princeton Environmental Institute who did not take part in the study, said the findings were "big news" and showed the potential limits of forests as a solution for combating global warming.

"Scientists have known for a long time that eventually forests would saturate and their carbon uptake would decline to zero over time as mortality of trees caught up with the increased growth rates," Anderegg said. "But what's really stunning to me is that we thought this saturation would occur decades from now, even towards or beyond the end of the century. This study shows that it really seems to have started in the 2000s. That's decades before we expected. This is bad news, because forests are currently one of the most effective carbon sinks."

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

October 20, 2014 5:37 PM

|

We can blame man for the altered composition of Eastern forests, but not climate change, according to a researcher in Penn State's College of Agricultural Sciences.

Forests in the Eastern United States remain in a state of "disequilibrium" stemming from the clear-cutting and large-scale burning that occurred in the late 1800s, contends Marc Abrams, a professor of forest ecology and physiology. And since about 1930, the Smokey Bear era, aggressive forest-fire suppression has had a far greater influence on shifts in dominant tree species than minor fluctuations in temperature.

"Looking at the historical development of Eastern forests, the results of the change in types of disturbances -- both natural and man-caused -- are much more significant than any change in climate," said Abrams. "Over the last 50 years, most environmental science has focused on the impact of climate change. In some systems, however, climate change impacts have not been as profound as in others. This includes the forest composition of the eastern U.S."

|

Scooped by

Prentiss & Carlisle

September 24, 2014 3:11 PM

|

Some trees are growing up to 70 percent faster than just a half century ago, as global warming supercharges their metabolism, German researchers report in a new study published in Nature Communications

Three decades ago, forest dieback was a hot topic, with the very survival of large forest ecosystems seemingly in doubt. But instead of a collapse, the latest studies indicate that forests have actually been growing at a faster rate. The new data from the Technische Universität München comes from forest plots that have been closely monitored since 1870. The forested areas are also representative of the typical climate and environmental conditions found in Central Europe.

“Our findings are based on a unique data pool,” maintains Prof. Hans Pretzsch from TUM’s Chair for Forest Growth and Yield, who headed up the study.

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...