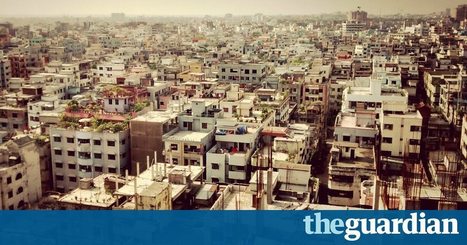

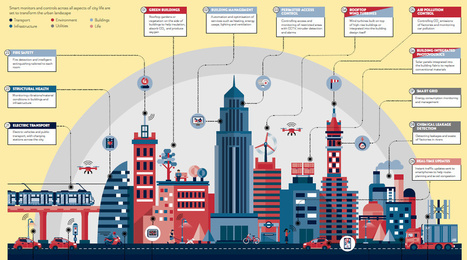

Evenly spread over all of the world’s mountains, deserts and other terrains, we would be standing 150 metres away from our nearest neighbours. In the most densely populated cities – from Dhaka to Medellin – we’re right on top of them

|

Scooped by

Judy Curtis / SIPR

onto Smart Cities & The Internet of Things (IoT) May 16, 2017 5:44 PM

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

Then something strange happened. Not only did modernist urbanism not seem to alleviate urban problems, but the aversion to high density began to be overturned. In the early 1960s Jane Jacobs tried to counter the ideas of Howard and Le Corbusier through her deep observation of ordering systems in high-density neighbourhoods, ideas that would later be taken up by the New Urbanists, who reacted against both modernist planning and the sprawl of American suburbia.

In 1990s Britain, Richard Rogers and the Urban Task Force advocated high density residential development along the lines of the city of Barcelona (density of 15,000 people/sq km), with its consistent superblocks as a civilised counterpart to suburbia.

This argument for density is echoed by geographers such as Richard Florida, who point out that the entire point of the city is the dense proximity of people, leading to what he calls “collision density”, and all the innovations of modern life.

Higher density city environments can also be more efficient, with greater public transport use and shorter journeys. Clustering dwellings together also means they share in each other’s energy loads – so density can have a significant effect on reducing carbon emissions.

“Anyone who believes that global warming is a real danger should see dense urban living as part of the solution,” as Harvard’s Ed Glaeser puts it.