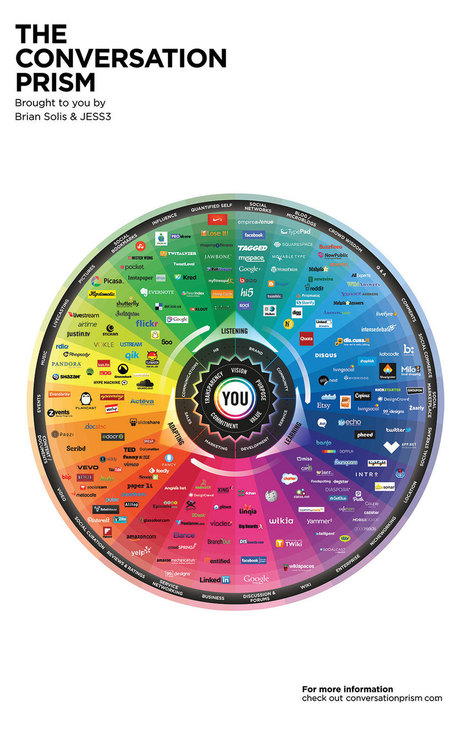

Amid the cacophony of a year-end media blitz that bombards us with listicles of the greatest scientific discoveries, the top papers, and the cutest animal stories, we seemed to have missed an important and serious contribution to our understanding of social media and its relationship to scientific publishing.

I was alerted to this paper the old-fashioned way–in conversation with a cardiovascular researcher–which I found rather odd, because research on social media typically attracts the attention of those who promote social media. Indeed, I can find no mention of it among those who follow bibliometric and sociometric research. Those #altmetrics hash-taggers seemed to have missed this paper, as did readers of the SIGMETRICS listserv.

The paper that slipped my attention was “A Randomized Trial of Social Media From Circulation,” which appeared online November 18, 2014 in the journal, Circulation.

In order to understand the effect of social media on the readership of their journal, the researchers (all members of the Circulation editorial board) designed a rigorous scientific trial in which half ofCirculation‘s original research articles were randomly assigned, upon publication, to be promoted in a social media campaign.

The campaign consisted of a Circulation Facebook blog post and Tweet, both of which contained the main point of the article, a key figure, and a toll-free link to the full-text version of the article. Articles in the control arm of the study didn’t receive any of these interventions.

The researchers measured the total number of page views (abstract + full text + PDF) for each article over 30 days. Did their promotion via social media have any effect? They write:

There was no difference in median 30-day page views (409 [social media] versus 392 [control], P=0.80). No differences were observed by article type (clinical, population, or basic science; P=0.19), whether an article had an editorial (P=0.87), or whether the corresponding author was from the United States (P=0.73).

While their results were resoundingly negative, they are still interesting, as prior studies have all reported positive results. I should note that prior studies were observational in nature, in which researchers searched for relationships between social media attention and some form of impact (downloads or citations). The problem with studying social media this way is that it becomes very difficult to understand what is causing what: Social media may increase the impact of a journal article; alternatively, important articles may simply attract a lot of social media attention.

If this problem sounds familiar, you’ll find a methodological critique of the RIN/Nature study on the relationship between Open Access and citations.

By randomly assigning articles into the social media and control arm of the experiment, the researchers can be pretty sure that the two groups are similar, in all respects, at the start of the experiment. If differences are observed at the end of the experiment, they can be pretty sure that they were caused by social media.

The fact that the researchers were unable to detect a difference in article downloads between the social media and control group suggests that their social media campaign had little (if any) effect. It also questions whether prior studies were successful in isolating and measuring the effects of social media. The true effects of social media may be much smaller than previously reported.

Like a study worthy of publication in a top medical journal, the researchers were careful about overgeneralizing their study. Cardiovascular researchers (and other bench and clinical researchers) are very different than computational biologists, social media researchers, and those who spend their days glued to their chairs and computers. While Circulation had more than 28,000 Facebook followers and nearly 5,000 Twitter followers, these online followers were qualitatively different (younger and predominantly male) than Circulation‘s traditional readers. This does not say that medical journals can categorically ignore this group of potential online readers, only that they may not be reflective ofCirculation’s readership as a whole.

Last week, I asked a room full of cardiovascular researchers if they used Twitter. One man in the audience put up his hand, but qualified that it was to keep up with his favorite soccer teams. When I asked about Facebook, two researchers put up their hands, but explained that it was part of their editorial duties to promote their journal.

Now I understand why I learned of this study by word-of-mouth.

Via Plus91

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

i would be interested to ssee replications of thsi study in our field. my impression is that psychologists, physios and other rehab researchers are more connected to twitter and other social media