Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

November 27, 3:30 AM

|

🎉 NEW PAPER PUBLISHED 🔬

Over a century after its introduction, the BCG vaccine continues to surprise us. Despite being given to billions of people, we still know remarkably little about what actually happens in the skin and blood in the hours and days right after intradermal BCG vaccination. Our team set out to change that.

In this study, conducted in Guinea-Bissau, we developed and validated a completely new experimental pipeline—bringing cutting-edge “omics” technologies into a difficult low-resource setting—to map the local (skin) and systemic (blood) immunological events following BCG.

Here are some of the most exciting methodological advances:

✨ 1. Spatial transcriptomics on 2 mm skin punch biopsies from healthy volunteers with and without a BCG scar

Using Nature’s 2020 Method of the Year, we assessed gene expression within the actual tissue architecture of the skin. For the first time, we could identify which cell types in the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis respond to BCG, and how.

✨ 2. Liquid biopsy: Cell-free RNA (cfRNA) Profiling

By capturing cell-free RNA from plasma, we non-invasively traced molecular signals released from the skin into the bloodstream. This offers the prospect of blood-based biomarkers that reflect tissue-level vaccine responses—a major step toward scalable immune monitoring.

✨ 3. Multiomics integration

We combined spatial transcriptomics, whole-blood transcriptomics, epigenetics, proteomics, metabolomics, & advanced computer-vision analysis of dermatoscopic images.

✨ 4. Precision study in a low-resource setting

From dermatoscopic imaging (using a smartphone-based system) to standardized storage/processing workflows (see Fig. 2 in the paper), we demonstrated that highly advanced immunology is possible in West Africa—opening the door for larger trials in populations where BCG’s effects matter most.

✨ 5. Capturing early immune events never previously characterized

By sampling on day 1, 7, & 14, and stratifying participants by presence/absence of pre-existing BCG scars, this project may shed light on why BCG given at birth has such profound survival benefits—and why revaccination responses differ.

Why this matters:

Most new TB vaccines build on BCG, yet the early steps of how BCG “trains” the immune system have never been fully mapped. Understanding these local and systemic events may be important for designing better vaccines—not only against TB, but potentially against a wide range of infections where BCG has shown non-specific (heterologous) benefits.

A huge thank you to our incredible collaborators across Guinea-Bissau, Denmark and Canada. And especially to the participants in Bissau who made this study possible.

If you’re interested in immunology, systems biology, vaccine innovation or (of course) vaccine epidemiology, let me hear your thoughts and/or connect with me here on LinkedIn.

📄 The full paper is available open access (link in comments) - & we have more interesting to come from this project.

|

Suggested by

Société Francaise d'Immunologie

November 26, 2020 2:16 PM

|

Abstract In recent years, the century‐old Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette‐Guerin (BCG) vaccine against tuberculosis (TB) has been re‐evaluated for its capacity to stem the global tide of TB. ...

|

Suggested by

Société Francaise d'Immunologie

May 30, 2020 2:22 AM

|

To Editor COVID-19, caused by the new corona virus (SARS-CoV-2), is an emerging, rapidly evolving disease that needs rapid intervention as it shows high spread mortality rates within very short time. Interestingly, the reported cases show different severity of symptoms, ranging from mild to severe with no symptoms in some cases. Although very limited studies investigated the immune responses toward COVID-19, a recent study conducted by researchers at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity in Australia, assessed the immune responses in the blood from a patient with COVID-19 disease with mild severity [1]. They looked at the cellular and humoral immune responses at different time points during the infection; i.e. before, during and after resolution of the disease and recovery of the patient. Their longitudinal analysis showed a robust immune response across different cell types associates with clinical recovery. These findings are similar to what the same group have reported before in patients with influenza infection [2], [3], Accordingly, we suggest a link between the quality of the immunity and recovery from COVID-19, at least in part, in patients with mild symptoms. Indeed, different susceptibilities to COVID-19 disease were observed between different age groups where children showed lower rate of infection than adults and elderly. Although the mechanism behind these differences in infection severity and susceptibility is not clear, one possible explanation could be the difference in the quality and quantity of the immune performance that is shaped by the history of recent infections and/or vaccinations. We present here the hypothesis that the resultant immunity against prior influenza infection would, at least in part, foster immunity against SARS-CoV-2. This hypothesis is supported by which the similarity in the quality of immunity toward both viruses. and by the previous studies showing cross reactivity of immunity between Flu and coronavirus [4] due to the similarity in their structures [5], [6]. Besides the cross reactivity effect, the anti-Flu immune responses can induce bystander immunity [7] that is expected to non-specifically augment immunity against other viral infection such as SARS-CoV-2. Furthermore, influenza vaccination itself would generate sustained immunity that overall enhance immunity against SARS-CoV-2. This would explain why the rate of SARS-CoV-2 in children is low since they catch flu more than adults do [8]. As such, it is expected that their immune systems be often alarmed against influenza, generating bystander immunity that harness the immune responses against related viral infection. Under this setting, we hypothesize that children generate multifactorial immunity with the repeated influenza exposure that would offer bystander immune response in case they became infected with the new SARS-CoV-2. It might be possible also that individuals who received prior Flu vaccination might show mild severity of COVID-19 because of Flu-induced bystander effect of the generated immune responses which itself might cross react against SARS-CoV-2. Due to this cross reactivity between Flu and SARS-CoV-2, we suggest that the Flu-induced bystander immunity is more of beneficial effects to COVID-19 than those suggested by MMR and BCG vaccines [9], [10]. Indeed, the zero COVID-19 patient (the Chinese patient suspected to be the first case infected with the new corona virus) who was released from the hospital couple of weeks after her diagnosis declared that the symptoms were almost like those of her repeated flu infection [11]. Given the safety of Flu vaccine in adult, we recommend the use of Flu vaccine, at least in part, as a bystander adjuvant to minimize the severity of COVID-19 disease. We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

|

Scooped by

Krishan Maggon

November 2, 2019 11:30 AM

|

Abstract Pathophysiology of graft failure (GF) occurring after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) still remains elusive. We measured serum levels of several different cytokines/chemokines in 15 children experiencing GF, comparing their values with those of 15 controls who had sustained donor cell engraftment. Already at day +3 after transplantation, patients developing GF had serum levels of interferon (IFN)-γ and CXCL9 (a chemokine specifically induced by IFNγ) significantly higher than those of controls (8859±7502 vs. 0 pg/mL, P=0.03, and 1514.0±773 vs. 233.6±50.1 pg/mlL, P=0.0006, respectively). The role played by IFNγ in HSCT-related GF was further supported by the observation that a rat anti-mouse IFNγ-neutralizing monoclonal antibody promotes donor cell engraftment in Ifngr1−/−mice receiving an allograft. In comparison to controls, analysis of bone marrow-infiltrating T lymphocytes in patients experiencing GF documented a predominance of effector memory CD8+ cells, which showed markers of activation (overexpression of CD95 and downregulation of CD127) and exhaustion (CD57, CD279, CD223 and CD366). Finally, we obtained successful donor engraftment in 2 out of 3 children with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis who, after experiencing GF, were re-transplanted from the same HLA-haploidentical donor under the compassionate use coverage of emapalumab, an anti-IFNγ monoclonal antibody recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of patients with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Altogether, these results suggest that the IFNγ pathway plays a major role in GF occurring after HSCT. Increased serum levels of IFNγ and CXCL9 represent potential biomarkers useful for early diagnosis of GF and provide the rationale for exploring the therapeutic/preventive role of targeted neutralization of IFNγ. Introduction Graft failure (GF), estimated to occur in 1-5% of cases after myeloablative conditioning and in up to 30% of cases after reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC),1 still remains a relevant cause of morbidity and mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).2 Despite a slight reduction of its incidence over the last decade, mortality after GF remains as high as 11%.3 To date, in the absence of effective treatment options, re-transplantation, from either the same, or whenever possible, a different donor is considered the treatment of choice.2 Currently identified risk factors for GF include: i) human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-disparity and sex mismatch in the donor/recipient pair; ii) presence of donor-specific antibodies (DSA) in the recipient; iii) T-cell depletion (TCD) of the graft; iv) ABO-blood group mismatch; v) use of RIC; vi) a diagnosis of non-malignant disorders (in particular thalassemia, severe aplastic anemia, SAA, and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, HLH); vii) viral infections; viii) low nucleated cell dose in the graft; and ix) the use of myelotoxic drugs in the post-transplant period.1–4 In the last two decades, several groups have investigated immune-mediated GF. In particular, it has been shown that immune-mediated GF is mainly caused by host T and natural killer (NK) cells surviving the conditioning regimen, through a classical alloreactive immune response against non-shared, major (in case of HLA-partially-matched HSCT) or minor (in case of fully HLA-matched HSCT) histocompatibility antigens.2,5,6 However, to date the molecular pathways involved in immune-mediated GF have not yet been completely clarified. Indeed, since the inhibition of different pathways (including perforin-FasL−, TNFR-1−, and TRAIL-dependent cytotoxicity) did not prove to be efficient in preventing GF, the pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for GF seem to be multiple and likely to be redundant.7 Nonetheless, consistently over the years, different groups have suggested a pivotal pathogenic role of IFNγ in GF pathophysiology,8–14 through both direct [e.g. inhibition of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) self-renewal, proliferative capacity, and multilineage differentiation]10,11 and indirect (e.g. induction of FAS expression on HSC, with increased apoptosis in the presence of activated cytotoxic T cells)8,12 effects. Despite these experimental data, there has still not been any in vivo characterization of GF in humans. Indeed, although the expansion of host CD8+ T cells in patients experiencing GF has been previously demonstrated in vivo,15,16 a more detailed characterization of this cell population is lacking. Thus, we started a prospective study aimed at better characterizing the pathophysiology of GF, focusing on the identification of biological markers that: (i) could predict early the occurrence of GF in the clinical setting; and (ii) could be used as a therapeutic target with clinically available biological agents. For this purpose, we broadly investigated cytokine and chemokine levels in peripheral blood (PB), as well as the cellular features in bone marrow (BM) biopsies of patients experiencing this complication. After confirming in vivo a role of IFNγ-pathway in the development of GF, we also investigated in an animal model of GF whether the sole inhibition of IFNγ would be able to prevent/treat GF. Finally, in view of these findings and the similarity between immune-mediated GF and HLH, we treated, in compassionate use (CU), with emapalumab, an anti-IFNγ monoclonal antibody recently approved for the treatment of HLH,17 three patients with primary HLH, who, after having experienced GF, underwent a second HSCT. Methods Patients Patients aged from 0.3 to 21 years, who received an allograft from any type of donor/stem cell source between January 1st 2016 and August 31st 2017 at the IRCCS Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital in Rome, Italy, were considered eligible for the study. All patients or legal guardians provided written informed consent, and the entire research was conducted under institutional review board approved protocols and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board approved the study. Cytokine profile In order to identify a cytokine/chemokine profile predictive of GF, PB samples were collected at different time points after HSCT: day 0, +3±2, +7±2, +10±2, +14±2, +30±2 after transplantation. Validated MesoScale Discovery (MSD, Rockville, MD, USA) platform-based immunoassay was used for the quantification of IFNγ, sIL2Rα, CXCL9, CXCL10, TNFα, IL6, IL10, and sCD163 serum levels. Bone marrow biopsy: histopathology analysis and immunofluorescence Bone marrow biopsies were obtained when GF was suspected. (Since BM characterization was a secondary end point of this study and BM aspiration is not routinely performed in this condition, parents/legal guardians could refuse the procedure.) Details on BM specimen preparation, histopathology analysis and immunofluorescence are reported in the Online Supplementary Appendix. Immune-phenotypic analysis The following monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were used: anti-CD3, CD4, CD8, CD25, CD27, CD28, CD45RA, CD45RO, CD56, CD57, CD62L, CD95, CD127, CD137, CD197, CD223 (Lag3), CD279 (PD1), and CD366 (TIM3) (BD Biosciences, NJ, Biolegend, CA and Affymetrix, CA, USA). In vivo murine model of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation rejection C57BL/6 Ifngr1−/− mice were used as recipient, while C57BL/6 Ifngr1+/+ were used as donor. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Swiss animal protection law. Details on experiments are reported in the Online Supplementary Appendix. Emapalumab administration in compassionate use to hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis patients experiencing graft failure Emapalumab (previously known as NI-0501), a fully human anti-IFNγ monoclonal antibody, was administered on a CU basis (after local ethical committee approval) to three patients affected by HLH who experienced GF after a first TCD HSCT from a partially-matched family donor (PMFD) with the aim of preventing flares of HLH and a second GF. The drug was administered by 1-hour intravenous infusion twice a week until sustained donor engraftment or GF. The dose varied between 1 and 6 mg/kg, based on pharmacokinetic data. Additional methods are presented in the Online Supplementary Appendix. Statistical analysis Unless otherwise specified, quantitative variables were reported as Mean±Standard Error of Mean (SEM); categorical variables were expressed as absolute value and percentage. Clinical characteristics of patients were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables, while the Mann-Whitney rank sum test or the Student t-test (two-sided) was used for continuous variables, as appropriate. For multiple comparison analyses, statistical significance was evaluated by a repeated measure ANOVA test, followed by a Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test for multiple comparisons. Results Patients’ characteristics During the study period, 15 consecutive patients who experienced GF were eligible for the study. Most of them were affected by non-malignant disorders characterized by a high risk of GF (e.g. SAA and HLH) and received a TCD allograft from a PMFD. Fifteen children, matched for transplant characteristics, who had sustained donor engraftment during the same period were used as controls. Patients’ and control characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Main transplant characteristics (i.e. conditioning regimen, type of donor, graft manipulation) were comparable between the two groups (except for a trend for a lower age in the GF group). Of the 15 patients experiencing GF, ten were tested for anti-HLA antibodies, which were detected in five patients (50%). Those who had a mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of anti-HLA antibodies >5000 received rituximab and underwent plasma-exchange to lower the value below the threshold of 5000 MFI;18 this treatment successfully reduced the MFI value in all cases. Table 1. Characteristics of patients who either did or did not experience graft failure (GF). Signs and symptoms of patients who either did or did not experience GF are detailed in Table 2. The most frequent sign associated with GF was fever, occurring at a median time of six days from the infusion of the graft (range 1-16 days). Moreover, both lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and ferritin increased in many patients (80% and 46.7%, respectively); these laboratory findings appeared late after HSCT (at a median of 11 and 10 days, respectively). All patients received steroids in an attempt to avoid GF, without benefit. Chimerism analysis performed on PB showed only recipient cells in all GF cases, while in all controls but one, who showed mixed chimerism, only donor-origin cells were found. Table 2. Signs and symptoms of patients who experienced graft failure (GF). Cytokine/chemokine profile Kinetics of IFNγ, CXCL9, IL10 and IL2Rα serum levels are shown in Figure 1A-D, while serum levels of TNFα, CXCL10, sCD163 and IL6 are shown in Figure 2A-D. Serum levels of these cytokines/chemokines differed between patients experiencing GF and controls, starting from the first days after the infusion of the graft. Notably, for IFNγ, CXCL9, IL10 and TNFα, this difference became statistically significant already at day +3 after HSCT. In particular, mean IFNγ levels at day +3 were 8859±7502 pg/mL in GF patients versus 0 pg/mL in controls (P=0.03); CXCL9 levels were 1514.0±773 pg/ml versus 233.6±50.1 pg/mL (P=0.0006); IL10 levels were 58.8±39.1 pg/mL versus 1.7±1.1 pg/mL (P=0.01); TNFα levels were 3.5±1.0 pg/mL versus 0.9±0.2 pg/mL (P=0.02). In this cohort, receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis on CXCL9 levels at day +3 showed an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.905 [95% Confidence Interval (CI) 0.709-0.987; P<0.0001] (Online Supplementary Figure S1); a cut-off value of 274.5 pg/mL had a sensitivity of 88.89% and a specificity of 78.57%. The ROC analysis of other markers, which were significantly increased at day +3 showed an AUC of 0.802 for TNFα (95%CI: 0.566-0.944; P=0.006), of 0.756 for IL10 (95%CI: 0.529-0.912; P=0.011) and of 0.682 for IFNγ (95%CI: 0.471-0.849; P=0.017). Figure 1. Cytokine/chemokine profile. Serum levels of interferon (IFN)-γ (A), CXCL9 (B), CXCL10 (C), and sIL2Rα (D) in patients who either did (red line) or did not (blue line) experience graft failure (GF). All graphs represent Mean and Standard Error of Mean for each variable. HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Figure 2. Cytokine/chemokine profile. Serum levels of TNFα (A), CXCL10 (B), sCD163 (C), IL6 (panel D). Red line: patients who experience graft failure (GF); blue line: controls. All graphs represent Mean and Standard Error of Mean for each variable. HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Since primary HLH patients commonly present increased IFNγ and its related chemokines serum levels during disease reactivation/flare (that is frequent after failure of HSCT19), we performed additional analyses excluding this subset of patients in order to validate the data in disorders other than HLH. Even after excluding HLH patients, CXCL9 and IL10 serum levels remained significantly higher in patients experiencing GF in comparison with controls (Online Supplementary Figure S2). Activation of macrophages and T lymphocytes characterizes graft failure in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation Bone marrow biopsies were obtained at time of GF in seven patients and were compared to those of five controls (obtained in a similar time period, i.e. between 2 and 3 weeks after HSCT). In all GF patients, evaluation of BM morphology showed different stages of GF with reduced cellularity (Figure 3A and Online Supplementary Figure S3A and B) as compared to patients with sustained donor engraftment (Online Supplementary Figure S4A). In GF patients, the percentage of myelocytes and erythroid precursors was reduced compared to controls (Figure 3B). Erythroid colonies were markedly smaller, with a higher percentage of premature erythroid cells. The megakaryocytic lineage was well represented in all GF cases, but with irregular distribution (Figure 3C). In several areas of the specimens, a remarkable number of apoptotic cells partially grouped in clusters was observed (Figure 3D). All biopsies showed stromal damage resulting in edema (Figure 3E). While the total number of CD68+ macrophages was comparable between GF patients and controls (Figure 4A), significantly higher percentages of CD68+ and CD163+ macrophages, with cellular fragments, erythrocytes and lipid vacuoles in their cytoplasm, (indicating activation and phagocytic activity) (Figure 3F and G and Online Supplementary Figure S3C and D), were observed in comparison to controls [median 80% (range 30-100%) vs. 0% (range 0-5%); P<0.0001] (Figure 4B and Online Supplementary Figure S4B and C). In all analyzed samples from GF patients, a significant increase in T lymphocytes (Figures 3H and 4A and Online Supplementary Figure S3G), with a predominance of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, expressing perforin, Granzyme B and TIA-1 (Figures 3I and J and 4A and Online Supplementary Figure S5) was observed. The Online Supplementary Appendix provides further details. Figure 3. Immunohistochemistry evaluation of bone marrow (BM) specimens in a patient experiencing graft failure (Pt #4). (A) Hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining of a BM specimen at 4X magnification. (B) Evaluation of erythroid colony spreading by glycophorin staining (10X). (C) Megakaryocyte distribution evaluated by CD61 expression (10X). (D) H&E staining at 40X showing apoptotic events. (E) H&E staining revealing stromal damage and edema development (40X). Characterization of the macrophage population by CD68 (F) and CD163 (G) staining (40X). Characterization and distribution of T lymphocytes by analysis of CD3 (H), CD4 (I), and CD8 (J) expression (10X). Figure 4. Immunohistochemistry characterization of bone marrow (BM) in patients who either did or did not experience graft failure (GF). (A) Comparison of absolute number of CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, CD68+, TIA-1+, perforin+ and granzyme+ cells in BM of GF patients and controls (CTRL). The total number of positive cell for each marker was counted in five fields per sample under 20-fold magnification and reported as Mean±Standard Deviation. (B) Percentages of CD68+ cells with hemophagocytic activity (i.e. showing cellular fragments, erythrocytes and lipid vacuoles in their cytoplasm) in BM of GF patients and CTRL. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. Polyclonal T-cell pattern with predominant CD8 effector memory phenotype effector memory phenotype In order to better characterize the role of T lymphocytes in GF, the TCR repertoire was initially analyzed in the CD3+ population, showing a polyclonal distribution of the Vβ chains (Online Supplementary Figure S6). Then, we extended our analysis on BM-infiltrating lymphocytes through flowcytometry in both controls and GF patients. Regarding NK (CD56+/CD3−) and γδ T cells (CD3+/CD4−/CD8−) no difference was observed between the two patient groups (data not shown). By contrast, in the αβ T-cell subset, the analysis revealed a significant difference in both CD4 (58.9%±13.4% vs. 7.6%±7.3%, controls vs. GF patients) and CD8 (25.9%±6.1% vs. 66.5%±18.2%, controls vs.GF patients) subsets (P<0.0001 and P=0.0018, respectively) (Figure 5A). We further characterized both CD4+ and CD8+ populations for the expression of memory markers. While no significant difference was detected in the CD4+ subpopulation, the CD8+ subset displayed a significant enrichment of effector memory T cells (EfM) (CD45RO+/CCR7-) (40.3±24.6% vs. 20.7%±7.3%, GF patients vs. CTRL patients; P=0.034) (Figure 5B and C) and a significant reduction of the naïve subset (CD45RA+/CCR7+) (18.6%±16.6% vs. 28.6%±12.1%, GF patients vs. controls; P=0.014). See Online Supplementary Appendix for further details. Figure 5. Immuno-characterization of the T lymphocytes present in bone marrow aspirates of patients who either did or did not experience graft failure (GF). (A) Flow cytometry analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ population in patients with GF and controls (CTRL). Distribution of naïve (CD45RA+/CCR7+), central memory (CD45RO+/CCR7+), effector memory (CD45RO+/CCR7−), effector terminal (CD45RA+/CCR7−), and NK-T (CD3+/CD56+) subsets in CD4+ (B) or CD8+ (C) T cells. Activation and exhaustion profile in both the CD4+ and CD8+ population by the analysis of CD95 (D), CD127 (E), and CD57 (F). (A, D, E, and F) Each patient or CTRL is represented by a symbol and a horizontal line marks the median. (B and C) The average (+) and Median±Standard Deviation are shown. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001. Increasing expression of activation and exhaustion markers on T cells during graft failure We evaluated the expression of several activation and exhaustion markers on infiltrating cells. As expected, in patients experiencing GF, both CD4+ and CD8+ cells displayed a significant activation profile, as demonstrated by the overexpression of CD95 (69.2%±23.0% vs. 93.9%±6.9% and 57.9%±27.2% vs. 98.35%±2.0%, controls vs. GF patients, respectively; P=0.021 and P=0.002) (Figure 5D) and downregulation of CD127 (recently shown to be associated with prolonged T-cell receptor stimulation20) on the proliferating CD8+ cells (69.3%±16.9% vs. 37.9%±18.8%, controls vs. GF patients, respectively; P=0.014) (Figure 5E). The expression of several exhaustion and senescence markers confirmed the status of prolonged activation of T lymphocytes located in the BM of GF patients, such as the upregulation of CD57 (CD57+: 10.2%±10.5% vs. 37.4%±12.4% and 34.7%±17.3% vs. 68.0%±18.8% controls vs. GF patients in CD4 and CD8 respectively; P=0.003 and P=0.011) (Figure 5F). See Online Supplementary Appendix for further details. Interferon-γ drives rejection of donor cells in Ifngr1−/–mice In order to understand if the sole IFNγ-inhibition would be sufficient to prevent GF, we used an established mouse model of GF.13 As previously reported by Rottman et al.,13 the infection of Ifngr1−/− mice with Bacillus Calmette– Guérin (BCG) resulted in a rapid increase of circulating IFNγ levels reaching a concentration of 11,000 pg/mL on day 20 post-infection (Figure 6A). HSCT performed at day 21, i.e. at the peak of IFNγ levels, resulted in poor chimerism as only 5% of the Ifngr1+/+ donor cells engrafted in the BCG-infected Ifngr1−/− recipient mice. After day 21 post-BCG infection, serum IFNγ levels gradually decreased to a steady state level of approximately 100 pg/mL. This decrease in IFNγ serum levels correlated with an increase in chimerism as the Ifngr1−/− recipient mice exhibited 19% HSC engraftment of donor cells at day 84 (Figure 6A). For further assessing the role played by IFNγ in GF, BCG-infected Ifngr1−/− recipient mice were given a neutralizing IFNγ mAb, XMG1.2, pre-and post-HSCT. Neutralization of IFNγ improved engraftment in BCG-infected Ifngr1−/−recipient mice because, at three months after the allograft, 45% of the lymphocytes were of donor origin (i.e. Ly5.1 positive), as compared to 19% in isotype control-treated mice (Figure 6B). In order to assess IFNγ activity and ensure neutralization by XMG1.2, the IFNγ-dependent chemokine CXCL9 was measured. A decrease in CXCL9 serum levels during the XMG1.2 treatment was observed, confirming IFNγ neutralization in contrast to isotype control-treated mice (Figure 6C). Once XMG1.2 treatment was interrupted, at day 42 post-BCG infection, a gradual increase in CXCL9 serum levels was observed, indicating restoration of IFNγ activity. Figure 6. Successful hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) chimerism in interferon (IFN)-γR1−/− mice correlates with low IFNγ activity; circulating CXCL9 levels is a biomarker of in vivo IFNγ activity. Ifngr1−/− mice (expressing the Ly5.2 congenic marker) were intravenously (i.v.) infected with 1,106 CFU of Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) (strain Pasteur 1173P2). After 14, 20, 28, 35 and 42 days mice were treated i.v. with 100 mg/kg of an isotype control (n=5) or the anti-mIFNγ, XMG1.2 (n=5). At day 21, mice were infused with bone marrow from Ifngr+/+ mice, expressing the Ly5.1 marker, after mild irradiation (550 rads). Chimerism, assessed by determining the surface expression of Ly5.1 and Ly5.2 on lymphocytes, was analyzed by flow cytometry at different time points after HSCT treatment. IFNγ levels were quantified at different time points by ELISA using the Luminex technology. (A) Graph represents the super-imposition of the chimerism (black straight line) and the IFNγ levels (gray dotted line) in the isotype control treated mice. (B) Graph represents the chimerism determined in mice treated with the isotype control (black straight line) or with the XMG1.2 (gray straight line) mAbs. (C) Ifngr1−/− mice were i.v. infected with 1.106 CFU of BCG (strain Pasteur 1173P2). After 14, 20, 28, 35 and 42 days mice were treated i.v. with 100 mg/kg of an isotype control (black straight line; n=5) or the anti-mIFNγ, XMG1.2 (gray straight line; n=5). At day 21, mice were transplanted with bone marrow from Ifngr+/+ mice, expressing the Ly5.1 marker, after mild irradiation (550 rads). At different time points post-BCG infection, circulating CXCL9 levels were quantified by ELISA using the Luminex technology. Ab: antibody. Emapalumab administration to patients after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation failure Three patients with primary HLH who experienced GF together with disease reactivation after a first TCD HSCT from a PMFD were treated with emapalumab both before and after the second HSCT (details are reported in Online Supplementary Table S1). For all these patients, the use of the other parent as a donor was not possible because of non-eligibility due to viral hepatitis. The CU of emapalumab was requested and obtained with the objective of controlling, without the use of myelosuppressive drugs other than those used in the conditioning regimen, HLH reactivation before and after a second HSCT. Emapalumab was administered at doses of 1-6 mg/kg every three days. Drug infusions were well tolerated and no significant safety event occurred. Two patients engrafted, while one rejected also the second HSCT without, however, experiencing a new HLH flare. This patient was successfully rescued with a third HSCT employing an unrelated cord blood (UCB) unit (notably, she received emapalumab until 3 days before UCB infusion). Remarkably, the two patients who engrafted upon treatment with emapalumab had very low levels of CXCL9 (i.e. below 102 pg/mL), indicating IFNγ neutralization, while this was not the case for the third patient at the time of the second transplant rejection. All these three patients are currently alive and disease-free, with a follow up of 24, 23 and 21 months, respectively. Discussion Diagnosis and treatment of GF in HSCT recipients remain challenging. Indeed, sign and symptoms (e.g. fever, increase in LDH or ferritin serum levels) associated with this transplant complication are non-specific; moreover, re-transplantation, although associated with relevant risk of tissue-toxicity and infections, represents the treatment of choice, since steroids and other immunosuppressive drugs are usually ineffective for rescuing these patients.2 In this study, we investigated humoral and cellular features of GF occurring after allogeneic HSCT in children, documenting a pivotal role played by IFNγ in the pathophysiology of this complication. Apart from the indirect evidence provided by the observation of very high rates of primary and secondary rejection after HLA-identical HSCT in patients with IFNγ-receptor 1 deficiency,21 currently available clinical data about the role of IFNγ in GF in humans remain limited. Interestingly, we found that GF is characterized by the same clinical (including high-grade fever, hepato/splenomegaly, hemophagocytosis in BM)22,23 and laboratory (i.e. increased ferritin, IFNγ, CXCL9, CXCL10, sCD163 and sIL-2Rα levels)24–28 features found in patients with HLH, where a central role of IFNγ has been shown.29 Our data indicate that IFNγ levels, and even more CXCL9 levels measured in PB, can predict GF with high sensitivity and specificity already at day +3 after graft infusion, while signs and symptoms of GF appear only later (see Table 2). Indeed, the current proposed risk score for GF determined on day +21 after HSCT, based on eight patient and transplant variables, showed good specificity, but low sensitivity.1 The high accuracy of CXCL9 in predicting GF, as indicated by the AUC of 0.905, renders this chemokine an ideal “candidate biomarker”, as stated by the 2014 National Institutes of Health consensus on biomarkers.30,31 CXCL9, also known as monokine induced by γ-interferon (MIG), is a chemokine specifically induced by IFNγ,32 and represent the most sensitive and specific of the soluble factors we analyzed. It binds to the chemokine receptor CXCL3 expressed on naïve T cells, Th1 CD4+ T cells, effector CD8+ T cells, as well as on NK and NKT cells, driving Th1 inflammation. Circulating CXCL9 levels have been shown to reflect the amount of IFNγ produced in organs, such as liver and spleen,25 which are the typical target of inflammation. This strong correlation with IFNγ produced in organs rather than in blood provides an explanation why, despite high CXCL9 serum levels, serum levels of IFNγ were found to be low or even undetectable in a few of our GF patients. Furthermore, elevated levels of CXCL9 have been related to graft rejection in solid organ transplantation (such as heart, kidney and lung transplantation),33–35 but, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating that the hyperproduction of IFNγ in GF occurring after HSCT results in increased CXCL9 serum levels. Among other cytokines/chemokines, we also observed increased levels of IL10, an important Th2 cytokine with anti-inflammatory properties, this finding being in agreement with the hyperproduction of this molecule recorded in patients with HLH.36 Our results are not only relevant for diagnostic purposes, but also suggest that IFNγ is a potential therapeutic target in GF. Indeed, independently of the mechanism of IFNγ-mediated GF (i.e. direct effect on HSC or HLH-like effect), our results support the investigation of IFNγ neutralization for prevention and/or treatment of GF in patients undergoing HSCT. The encouraging efficacy and safety data reported from the ongoing study in primary HLH with emapalumab (NI-0501), an anti-IFNγ monoclonal antibody,17,37 provides additional support for the rationale for using this drug.38 The data we generated in the murine model of GF confirm and extend the role played by IFNγ previously demonstrated by Rottman et al.13 Moreover, we also show that the sole neutralization of IFNγ, without the administration of anti-IL12 (employed in the experiments reported by Rottman et al.),13 is able to improve engraftment. The observation that decreased CXCL9 production correlates with improved HSCT chimerism provides further support to a therapeutic intervention aimed at neutralizing IFNγ-pathway signaling. Finally, the data obtained in the three patients treated on a CU basis indicate that the use of an anti-IFNγ monoclonal antibody is safe also in a very fragile population, namely infants with a previous GF undergoing a second HSCT. Four out of the seven patients we studied who underwent BM aspirate and biopsy showed evidence of hemophagocytosis. Indeed, it has been shown that an increased number of hemophagocytic macrophages in the BM obtained 14±7 days after HSCT is associated with higher risk of death due to GF.39 Moreover, in a cohort of adult patients receiving cord blood transplantation, GF was strictly related to the occurrence of HLH manifestations.23 Recently, in a retrospective study on peri-engraftment BM samples from 32 adult patients, Kawashima et al. proposed two histological measures, namely macrophage ratio and CD8+ ratio (defined as the ratio between the macrophage or CD8+ lymphocyte number on the total nucleated cell number), as predictors of GF at day +14.15 Despite some preliminary studies characterizing host T cell expansion in patients with GF,15,16 no information is available regarding the phenotype of these cells. Our data indicate an active role of T lymphocytes in mediating GF. As previously reported,15 in these patients, the mononuclear infiltrate is mainly constituted by cytotoxic CD8+ lymphocytes with a predominant effector memory phenotype. This population was demonstrated to be activated, proliferating and cytotoxic, expressing specific molecules, such as Granzyme B, Perforin and TIA-1, involved in target-killing, as well as various activation and proliferation markers. Interestingly, we observed that CD8+ lymphocyte expansion is predominantly polyclonal, suggesting that the immune response is directed towards several antigens and not against few immunodominant epitopes. However, a significant enrichment of certain β clones was found. The cytopathic effect was clearly demonstrated by apoptotic cells surrounding proliferating T cells, which are long-term activated, as demonstrated by the expression of several exhaustion markers.40,41 Furthermore, the remaining γ/d and CD4+ T-cell populations are similarly expressing exhaustion markers, underlying an over-stimulated environment. Notably, a particular behavior was observed in the NKT-cell population with a significant reduction of CD8+ NKT, probably due to their activation and a significant increase of CD4+ NKT. The role of these cells is yet to be fully elucidated, although they were shown to be able to prevent pancreatic islet transplant rejection, but also to sustain CD8+ T-cell expansion.42,43 Given these data, a treatment able to interrupt the overproduction of molecules responsible for inflammation,33 such as an anti-IFNγ, could be beneficial in this setting. Fifty percent of tested patients had anti-HLA antibodies: all those with positivity >5,000 MFI received a desensitization therapy in order to lower the antibody title with the aim of reducing the risk of GF. Although we cannot exclude a role of anti-HLA antibodies in causing GF in our patients, all five positive patients showed increased values of IFNγ and/or related cytokines after HSCT. Thus, we can hypothesize that there may be a common final pathway and/or combined action (like that reported in solid organ transplantation)44 between humoral and cellular mechanisms sustaining GF. Limitations of this study are the lack of a validation cohort and the relatively small number of patients included in the study. Another important limitation is that most patients experiencing GF that we report were transplanted from a PMFD after a TCD procedure (both being well-known risk factors for GF);2,3 thus, our results should be further validated in other transplant settings, especially when post-transplant pharmacological graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis is used. Indeed, the use of calcineurin inhibitors or other immunosuppressive agents can modify IFNγ (and related cytokines) secretion kinetics.45 Overall, our data suggest that immune-mediated GF may share clinical and laboratory characteristics with HLH. Besides providing evidence for further investigating the use of markers to allow a non-invasive, prompt identification of patients at high risk of developing this severe complication of HSCT, the increased serum levels of IFNγ and CXCL9 found in GF patients provide a rationale for investigating a targeted therapy (i.e. anti-IFNγ therapy) in this complication. We are currently designing a clinical trial on the use of emapalumab for prevention and/or treatment of GF in patients at high risk of developing this complication. Footnotes Check the online version for the most updated information on this article, online supplements, and information on authorship & disclosures: www.haematologica.org/content/104/11/2314 Funding This work was supported by “Ricerca corrente” (Ministero della Salute) (PM), Investigator Grant 2015 Id. 17200 by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) (FL) and by Novimmune SA, Switzerland. Received January 7, 2019. Accepted February 18, 2019. Copyright© 2019 Ferrata Storti Foundation Material published in Haematologica is covered by copyright. All rights are reserved to the Ferrata Storti Foundation. Use of published material is allowed under the following terms and conditions: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/legalcode. Copies of published material are allowed for personal or internal use. Sharing published material for non-commercial purposes is subject to the following conditions: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/legalcode, sect. 3. Reproducing and sharing published material for commercial purposes is not allowed without permission in writing from the publisher. References 1.↵Olsson RF, Logan BR, Chaudhury S, et al. Primary graft failure after myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Leukemia. 2015;29(8):1754–1762.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 2.↵Locatelli F, Lucarelli B, Merli P. Current and future approaches to treat graft failure after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15(1):23–36.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 3.↵Olsson R, Remberger M, Schaffer M, et al. Graft failure in the modern era of allogeneic hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(4):537–543.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 4.↵Cluzeau T, Lambert J, Raus N, et al. Risk factors and outcome of graft failure after HLA matched and mismatched unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a study on behalf of SFGM-TC and SFHI. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51(5):687–691.OpenUrl 5.↵Masouridi-Levrat S, Simonetta F, Chalandon Y. Immunological Basis of Bone Marrow Failure after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Front Immunol. 2016;7:362.OpenUrlCrossRef 6.↵Murphy WJ, Kumar V, Bennett M. Acute rejection of murine bone marrow allografts by natural killer cells and T cells. Differences in kinetics and target antigens recognized. J Exp Med. 1987;166(5):1499–1509. 7.↵Komatsu M, Mammolenti M, Jones M, Jurecic R, Sayers TJ, Levy RB. Antigen-primed CD8+ T cells can mediate resistance, preventing allogeneic marrow engraftment in the simultaneous absence of perforin-CD95L-TNFR1-and TRAIL-dependent killing. Blood. 2003;101(10):3991–3999. 8.↵Chen J, Feng X, Desierto MJ, Keyvanfar K, Young NS. IFN-γ-mediated hematopoietic cell destruction in murine models of immune-mediated bone marrow failure. Blood. 2015;126(24):2621–2631. 9.Chen J, Lipovsky K, Ellison FM, Calado RT, Young NS. Bystander destruction of hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells in a mouse model of infusion-induced bone marrow failure. Blood. 2004;104(6):1671–1678. 10.↵de Bruin AM, Demirel O, Hooibrink B, Brandts CH, Nolte MA. Interferon-γ impairs proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Blood. 2013;121(18):3578–3585. 11.↵Lin FC, Karwan M, Saleh B, et al. IFN-γ causes aplastic anemia by altering hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell composition and disrupting lineage differentiation. Blood. 2014;124(25):3699–3708. 12.↵Maciejewski J, Selleri C, Anderson S, Young NS. Fas antigen expression on CD34+ human marrow cells is induced by interferon γ and tumor necrosis factor α and potentiates cytokine-mediated hematopoietic suppression in vitro. Blood. 1995;85(11): 3183–3190. 13.↵Rottman M, Soudais C, Vogt G, et al. IFN-γ mediates the rejection of haematopoietic stem cells in IFN-γR1-deficient hosts. PLoS Med. 2008;5(1):e26.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 14.↵Selleri C, Maciejewski JP, Sato T, Young NS. Interferon-γ constitutively expressed in the stromal microenvironment of human marrow cultures mediates potent hematopoietic inhibition. Blood. 1996; 87(10):4149–4157. 15.↵Kawashima N, Terakura S, Nishiwaki S, et al. Increase of bone marrow macrophages and CD8+ T lymphocytes predict graft failure after allogeneic bone marrow or cord blood transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52(8):1164–1170.OpenUrl 16.↵Koyama M, Hashimoto D, Nagafuji K, et al. Expansion of donor-reactive host T cells in primary graft failure after allogeneic hematopoietic SCT following reduced-intensity conditioning. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(1):110–115.OpenUrl 17.↵Jordan M, Locatelli F, Allen C, et al. A Novel Targeted Approach to the Treatment of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) with an Anti-Interferon γ (IFN γ) Monoclonal Antibody (mAb), NI-0501: First Results from a Pilot Phase 2 Study in Children with Primary HLH. Blood. 2015; 126(23):3.OpenUrl 18.↵Ciurea SO, Thall PF, Milton DR, et al. Complement-Binding Donor-Specific Anti-HLA Antibodies and Risk of Primary Graft Failure in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(8):1392–1398.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 19.↵Messina C, Zecca M, Fagioli F, et al. Outcomes of Children with Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis Given Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Italy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(6):1223–1231.OpenUrl 20.↵Utzschneider DT, Alfei F, Roelli P, et al. High antigen levels induce an exhausted pheno type in a chronic infection without impairing T cell expansion and survival. J Exp Med. 2016;213(9):1819–1834. 21.↵Roesler J, Horwitz ME, Picard C, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for complete IFN-γ receptor 1 deficiency: a multi-institutional survey. J Pediatr. 2004; 145(6):806–812. 22.↵Abe Y, Choi I, Hara K, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome: a rare complication of allogeneic nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29(9):799–801. 23.↵Takagi S, Masuoka K, Uchida N, et al. High incidence of haemophagocytic syndrome following umbilical cord blood transplantation for adults. Br J Haematol. 2009; 147(4):543–553.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 24.↵Bracaglia C, de Graaf K, Pires Marafon D, et al. Elevated circulating levels of interferon-γ and interferon-γ-induced chemokines characterise patients with macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):166–172. 25.↵Buatois V, Chatel L, Cons L, et al. Use of a mouse model to identify a blood biomarker for IFNγ activity in pediatric secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Transl Res. 2017;180:37–52.e2.OpenUrl 26.Henter JI, Elinder G, Soder O, Hansson M, Andersson B, Andersson U. Hypercytokinemia in familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 1991; 78(11):2918–2922. 27.Xu XJ, Tang YM, Song H, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a specific cytokine pattern in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in children. J Pediatr. 2012;160(6):984–990.e1. 28.↵Yang SL, Xu XJ, Tang YM, et al. Associations between inflammatory cytokines and organ damage in pediatric patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Cytokine. 2016;85:14–17.OpenUrl 29.↵Jordan MB, Hildeman D, Kappler J, Marrack P. An animal model of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): CD8+ T cells and interferon γ are essential for the disorder. Blood. 2004;104(3):735–743. 30.↵Paczesny S. Biomarkers for posttransplantation outcomes. Blood. 2018;131(20):2193–2204. 31.↵Paczesny S, Hakim FT, Pidala J, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: III. The 2014 Biomarker Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(5):780–792.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 32.↵Groom JR, Luster AD. CXCR3 ligands: redundant, collaborative and antagonistic functions. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011;89(2): 207–215. 33.↵Fahmy NM, Yamani MH, Starling RC, et al. Chemokine and chemokine receptor gene expression indicates acute rejection of human cardiac transplants. Transplantation. 2003;75(1):72–78. 34.Gupta A, Broin PO, Bao Y, et al. Clinical and molecular significance of microvascular inflammation in transplant kidney biopsies. Kidney Int. 2016;89(1):217–225.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 35.↵Medoff BD, Wain JC, Seung E, et al. CXCR3 and its ligands in a murine model of obliterative bronchiolitis: regulation and function. J Immunol. 2006;176(11):7087–7095. 36.↵An Q, Hu SY, Xuan CM, Jin MW, Ji Q, Wang Y. Interferon γ and interleukin 10 polymorphisms in Chinese children with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(9). 37.↵Locatelli F, Jordan M, Allen C, et al. Safety and efficacy of emapalumab in pediatric patients with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):LBA–6.OpenUrl 38.↵Prencipe G, Caiello I, Pascarella A, et al. Neutralization of interferon-γ reverts clinical and laboratory features in a mouse model of macrophage activation syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(4):1439–1449.OpenUrl 39.↵Imahashi N, Inamoto Y, Ito M, et al. Clinical significance of hemophagocytosis in BM clot sections during the peri-engraftment period following allogeneic hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012; 47(3):387–394.OpenUrlPubMed 40.↵Ferris RL, Lu B, Kane LP. Too much of a good thing? Tim-3 and TCR signaling in T cell exhaustion. J Immunol. 2014;193(4):1525–1530. 41.↵Jin HT, Anderson AC, Tan WG, et al. Cooperation of Tim-3 and PD-1 in CD8 T-cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010; 107(33):14733–14738. 42.↵Ikehara Y, Yasunami Y, Kodama S, et al. CD4(+) Valpha14 natural killer T cells are essential for acceptance of rat islet xenografts in mice. J Clin Invest. 2000; 105(12):1761–1767. 43.↵Lin H, Nieda M, Rozenkov V, Nicol AJ. Analysis of the effect of different NKT cell subpopulations on the activation of CD4 and CD8 T cells, NK cells, and B cells. Exp Hematol. 2006;34(3):289–295.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 44.↵Zeglen S, Zakliczynski M, Wozniak-Grygiel E, et al. Mixed cellular and humoral acute rejection in elective biopsies from heart transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2009; 41(8):3202–3205.OpenUrlCrossRefPubMed 45.↵Grant CR, Holder BS, Liberal R, et al. Immunosuppressive drugs affect interferon (IFN)-γ and programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) kinetics in patients with newly diagnosed autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2017;189(1):71–82.OpenUrl

|

Scooped by

Krishan Maggon

February 8, 2019 5:07 AM

|

The fact that the incidence is highest in people who are immunosuppressed provides some support for the idea that Merkel cell carcinoma is an immunogenic cancer, one that is related to immune function, and a good candidate for immunotherapy. The National Cancer Institute defines immunotherapy as “a type of therapy that uses substances to stimulate or suppress the immune system to help the body fight cancer, infection, and other diseases. Some types of immunotherapy only target certain cells of the immune system. Others affect the immune system in a general way. Types of immunotherapy include cytokines, vaccines, bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG), and some monoclonal antibodies.” Pembrolizumab is a monoclonal antibody. Other centers participating in the trial are University of Washington/Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and Bloomberg–Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, Emory University, Moffitt Cancer Center, Mount Sinai Medical Center, University of California San Francisco, Yale University, Stanford University, University of Pittsburgh, Duke University Medical Center, Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, City of Hope, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Cancer Immunotherapy Trials Network, University of Washington, and Axio Research. The research was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute, the Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) patient gift fund at University of Washington, the Kelsey Dickson MCC Challenge Grant from the Prostate Cancer Foundation, the Al Copeland Foundation, and Merck, which provided pembrolizumab and partial funding for this study.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

May 10, 2018 2:44 PM

|

Infections take their greatest toll in early life necessitating robust approaches to protect the very young. Here we review the rationale, current state and future research directions for one such approach: neonatal immunization. Challenges to neonatal immunization include natural concern about safety as well as a distinct neonatal immune system that is generally polarized against Th1 responses to many stimuli such that some vaccines that are effective in adults are not in newborns. Nevertheless, neonatal immunization could result in high population penetration as birth is a reliable point of healthcare contact, and offers an opportunity for early protection of the young, including preterm newborns who are deficient in maternal antibodies. Despite distinct immunity and reduced responses to some vaccines, several vaccines have proven safe and effective at birth. While some vaccines such as polysaccharide vaccines have little effectiveness at birth, hepatitis B vaccine (HBV) can prime at birth and requires multiple doses to achieve protection, whereas the live attenuated Bacille Calmette Guérin (BCG), may offer single shot protection, potentially in part via heterologous (“nonspecific”) beneficial effects. Additional vaccines have been studied at birth including those directed against pertussis, pneumococcus, Haemophilus influenza type B (Hib) and rotavirus providing important lessons. Current areas of research in neonatal vaccinology include characterization of early lif

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

March 23, 2018 10:07 AM

|

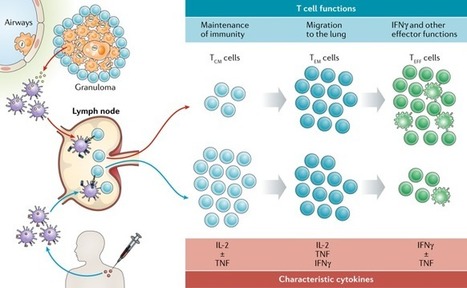

Tuberculosis (TB) is a granulomatous disease that has affected humanity for thousands of years. The production of cytokines, such as IFN-γ and TNF-α, is fundamental in the formation and maintenance of granulomas and in the control of the disease. Recently, the introduction of TNF-α-blocking monoclonal antibodies, such as Infliximab, has brought improvements in the treatment of patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, but this treatment also increases the risk of reactivation of latent tuberculosis. Our objective was to analyze, in an in vitro model, the influence of Infliximab on the granulomatous reactions and on the production of antigen-specific cytokines (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-12p40, IL-10 and IL-17) from beads sensitized with soluble Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) antigens cultured in the presence of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from TB patients. We evaluated 76 individuals, with tuberculosis active, treated and subjects with positive PPD. Granuloma formation was induced in the presence or absence of Infliximab for up to 10 days. The use of Infliximab in cultures significantly blocked TNF-α production (p <0.05), and led to significant changes in granuloma structure, in vitro, only in the treated TB group. On the other hand, there was a significant reduction in the levels of IFN-γ, IL-12p40, IL-10 and IL-17 after TNF-α blockade in the three experimental groups (p <0.05). Taken together, our results demonstrate that TNF-α blockade by Infliximab directly influenced the structure of granuloma only in the treated TB group, but negatively modulated the production of Th1, Th17 and regulatory T cytokines in the three groups analyzed.

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

July 29, 2015 7:47 AM

|

by Paulo Ranaivomanana, Vaomalala Raharimanga, Patrice M.

|

|

Scooped by

Gilbert C FAURE

December 30, 2020 5:36 AM

|

Click on the article title to read more.

|

Scooped by

Krishan Maggon

October 8, 2020 1:40 PM

|