Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

September 10, 2016 1:23 PM

|

"Not only did we fail to imagine what the web would become, we still don't see it today. We are oblivious to the miracle it has blossomed into. Twenty years after its birth the immense scope of the web is hard to fathom. The total number of web pages including those that are dynamically…

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

March 16, 2016 1:30 PM

|

Smarter groups tend to be more cooperative. This finding, which shows up both in lab experiments and in free-form negotiation studies, means that intelligent groups have more social intelligence. That helps explain why countries with high average test scores usually have stronger economies and more effective governments.

|

Rescooped by

Howard Rheingold

from Learning & Mind & Brain

July 9, 2015 4:47 PM

|

Cooperative behaviour is not an instinctive impulse or deliberate choice, but a learning process.

Via Julie Tardy, Miloš Bajčetić

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

February 9, 2015 4:35 PM

|

A new book by David Sloan Wilson provides some thoughtful answers. Wilson is a professor of biology and anthropology at Binghamton University, and one of the leading evolutionary theorists of his generation. He has written scholarly and popular books on the evolution of altruism, religion as a multilevel adaptation, and, in The Neighborhood Project: Using Evolution to Improve My City, One Block at a Time (Little, Brown and Company, 2011), on applying evolutionary principles to better the quality of life in Binghamton, N.Y. His new book, Does Altruism Exist? Culture, Genes, and the Welfare of Others, is part of a series of little books on big ideas from Yale University Press, and a concise summary of his life’s work.

A cottage industry has grown in recent years around theories purporting to explain how our brains produce empathy, morality, and good will.

Like Darwin,Wilson begins with the animals, specifically bees, which, when their colony splits by swarming, send out scouts to search out a new nest cavity. Miraculously, when the individual scouts return, each having visited a cavity or two at most, and therefore lacking the requisite big picture to "argue" their case, a collective decision about the best option is nonetheless made based on their dancelike interactions. This collective process is uncannily similar in pattern to the one observed between individual neurons in the brains of rhesus monkeys that are trying to determine the principal direction of movement of haphazard dots on a screen. The "group mind" of the bees seems to work in almost identical ways to the single, multimillion-neuron mind of the monkey.

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

February 4, 2015 3:52 PM

|

Group size in early hunter-gather conditions was limited by the cognitive capacity required to ‘compute’ social organizational parameters (e.g. pecking order, status and role structures, divisions-of-labor, kinship networks, and territorial embeddedness). Group size was also limited by the mechanism that enabled the memory of all individual exchanges and other forms of ‘moral’ accounting history essential to maintaining group cohesiveness.

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

January 8, 2015 12:11 PM

|

A Natural History of Human Thinking [Michael Tomasello] on Amazon.com. Tool-making or culture, language or religious belief: ever since Darwin, thinkers have struggled to identify what fundamentally differentiates human beings from other animals. In this much-anticipated book Michael Tomasello weaves his twenty years of comparative studies of humans and great apes into a compelling argument that cooperative social interaction is the key to our cognitive uniqueness. Once our ancestors learned to put their heads together with others to pursue shared goals, humankind was on an evolutionary path all its own.

Tomasello argues that our prehuman ancestors, like today's great apes, were social beings who could solve problems by thinking. But they were almost entirely competitive, aiming only at their individual goals. As ecological changes forced them into more cooperative living arrangements, early humans had to coordinate their actions and communicate their thoughts with collaborative partners. Tomasello's "shared intentionality hypothesis" captures how these more socially complex forms of life led to more conceptually complex forms of thinking. In order to survive, humans had to learn to see the world from multiple social perspectives, to draw socially recursive inferences, and to monitor their own thinking via the normative standards of the group. Even language and culture arose from the preexisting need to work together. What differentiates us most from other great apes, Tomasello proposes, are the new forms of thinking engendered by our new forms of collaborative and communicative interaction.

A Natural History of Human Thinking is the most detailed scientific analysis to date of the connection between human sociality and cognition.

|

Rescooped by

Howard Rheingold

from E-Learning-Inclusivo (Mashup)

December 15, 2014 3:21 PM

|

Peeragogy is a collection of techniques for collaborative learning and collaborative work. By learning how to “work smart” together, we hope to leave the world in a better state than it was when we arrived. Indeed, humans have always learned from each other. But for a long time – until the advent of the Web and widespread access to digital media – schools have had an effective monopoly on the business of learning. Now, with access to open educational resources and free or inexpensive communication platforms, groups of people can learn together outside as well as inside formal institutions. All of this prompted us to reconsider the meaning of “peer learning.”

The Peeragogy Handbook isn’t a normal book. It is an evolving guide, and it tells a collaboratively written story that you can help write. Using this book, you will develop new norms for the groups you work with — whether online, offline, or both. Every section includes practical ideas you can apply to build and sustain strong and exciting collaborations. When you read the book, you will get to know the authors and will see how we have applied these ideas: in classrooms, in research, in business, and more. You’ll meet Julian, one of the directors of a housing association; Roland, a professional journalist and change-maker; Charlie, a language teacher and writer who works with experimental media for fun and profit; and Charlotte, an indie publisher who wants to become better at what she does by helping others learn how to do it well too — as well as many other contributors from

around the globe.

Via Edumorfosis, juandoming

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

December 10, 2014 1:49 PM

|

“There is an emerging sharing economy workforce,” Peers executive director Shelby Clark told BuzzFeed News. “It’s totally different than anything we’ve ever seen before, it has new needs. So we need to create new products and services that meet those needs.”

To that end, Peers, an online community for sharing economy workers — which according to Clark boasts a quarter of a million people in the network — is rolling out two of the first programs to be made available to its networks of workers on the site’s support marketplace: Homesharing Liability Insurance and Keep Driving.

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

November 16, 2014 4:52 PM

|

It's an information superhighway that speeds up interactions between a large, diverse population of individuals. It allows individuals who may be widely separated to communicate and help each other out. But it also allows them to commit new forms of crime.

No, we're not talking about the internet, we're talking about fungi. While mushrooms might be the most familiar part of a fungus, most of their bodies are made up of a mass of thin threads, known as a mycelium. We now know that these threads act as a kind of underground internet, linking the roots of different plants. That tree in your garden is probably hooked up to a bush several metres away, thanks to mycelia.

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

September 11, 2014 4:01 PM

|

"According to a United Nations report published Wednesday, the ozone layer — which protects Earth’s inhabitants from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays — is slowly rebuilding itself. Almost more impressive is the fact that the prevention of this harmful hole is happening because of a global treaty: the Montreal Protocol."

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

August 4, 2014 1:40 PM

|

"Our theory is thus about processes in the human mind. Those processes evolve in tandem with culture. They require culture for their support while they enable culture through their capacities. In particular, we believe that the genetic elements of culture are to be found in the external world, in the properties of artifacts and behaviors, not inside human heads. Hays first articulated this idea in his book on the evolution of technology and I have developed it in my papers Culture as an Evolutionary Arena"

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

May 26, 2014 12:53 PM

|

Professor Elinor Ostrom’s work was extremely influential worldwide, and this includes important contributions to Mexican commons governance. From water governance to forest stewardship to small-scale fisheries’ management, Ostrom’s institutional

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

May 10, 2014 1:06 AM

|

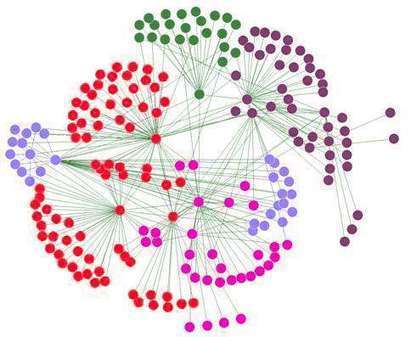

"This chapter addresses the governance of a specific type of constructed common-pool resource, online creation communities (OCCs).OCCs are communities of individuals that mainly interact via a platform of online participation, with the goal of building and sharing a common-pool resource resulting from collaboratively systematizing and integrating dispersed information and knowledge resources. Previous research of the governance of OCCs has been based on analyzing specific aspects of the governance. However, there has been a gap in the literature, one of lacking a comprehensive and holistic view of what governance means in collective action online. "

|

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

June 2, 2016 3:04 PM

|

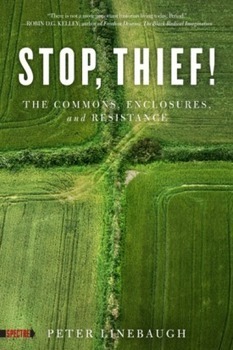

The tragedy of the commons, a concept described by ecologist Garrett Hardin, paints a grim view of human nature. The theory goes that, if a resource is shared, individuals will act in their own self-interest, but agains

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

July 13, 2015 2:19 PM

|

The two aspects of being human that set us apart from other mammals are metacognition and the deep desire to belong or feel felt. Our sense of needing to belong to a group is an inherited part of our neurobiology, and collaboration with others is the desired outcome. Metacognition is our brains' miraculous innate ability to self-assess, think about our thinking, and reshape our perspectives.

Feeling the emotions of others, social acceptance, and cooperation are critical to our early development of the identity and industry stages. Author and motivational speaker Daniel Pink states that the future belongs to conceptual cooperative thinkers.

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

March 6, 2015 12:26 PM

|

San Antonio's taxi mayhem had demonstrated the century-old “tragedy of the commons” theory: That shepherds could not be trusted to sustainably share a public resource such as a piece of grassland, because each would be more likely to act in his or her own self-interest and overgraze — to the detriment of the common good.

Elinor Ostrom won the Nobel Prize in economics in 2009 for debunking that theory, using as proof the cooperative acequia canal systems such as those that irrigated croplands around the Alamo, parts of which still exist near Mission San Juan Capistrano.

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

February 4, 2015 3:55 PM

|

The next series of posts I want to explore how information and identity are shaped by and shape fundamental social constraints.

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

February 4, 2015 3:06 PM

|

Tonnies’ distinction between community and civil society profoundly shaped 20th century social science and inspired anthropologists, sociologists and cross-cultural psychologists to explore how different social groups organized themselves according to these different principles.

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

December 25, 2014 7:15 PM

|

Communities of practice are formed by people who engage in a process of collective learning in a shared domain of human endeavor: a tribe learning to survive, a band of artists seeking new forms of expression, a group of engineers working on similar problems, a clique of pupils defining their identity in the school, a network of surgeons exploring novel techniques, a gathering of first-time managers helping each other cope. In a nutshell:

Communities of practice are groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly.

Note that this definition allows for, but does not assume, intentionality: learning can be the reason the community comes together or an incidental outcome of member’s interactions. Not everything called a community is a community of practice. A neighborhood for instance, is often called a community, but is usually not a community of practice.

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

December 15, 2014 1:08 PM

|

Both collaborative behaviours (working together for a common goal) and cooperative behaviours (sharing freely without any quid pro quo) are needed in the network era. Most organizations focus on shorter term collaborative behaviours, but networks thrive on cooperative behaviours, where people share without any direct benefit. This is the major shift we need in creating Enterprise 2.0 or social businesses. Being “social” means being human, and humans are much more than economic units. We like to be helpful and we like to get recognition. We need more than extrinsic compensation and our behaviour on Wikipedia and online social networks proves this. For the most part, we like to help others. This is cooperation, and it makes for more resilient networks. Better networks are better for business.

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

December 8, 2014 1:50 PM

|

The backlash against unethical labor practices in the “collaborative sharing economy” has been overplayed. Recently, The Washington Post, New York Times and others started to rail against online labor brokerages like Taskrabbit, Handy, and Uber because of an utter lack of concern for their workers. At the recent Digital Labor conference, my colleague McKenzie Wark proposed that the modes of production that we appear to be entering are not quite capitalism as classically described. “This is not capitalism,” he said, “this is something worse.” [1]

But just for one moment imagine that the algorithmic heart of any of these citadels of anti-unionism could be cloned and brought back to life under a different ownership model, with fair working conditions, as a humane alternative to the free market model.

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

October 15, 2014 2:00 PM

|

Cooperative boardgames require some mental readjustment. Your fellow players aren’t your opponents; they’re on your team! Either you all beat the game, or you all lose!

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

September 7, 2014 4:33 PM

|

"The camera never moves, the interval never changes, there’s no crazy ‘flow-motion’ skills involved and what is captured isn’t a picturesque landscape… and yet, this time-lapse gabbed us and wouldn’t let go. What’s captured in this three-and-a-half-minute time-lapse is an Amish barn raising… about a month of construction done in all of 10 hours. But more than that, it’s the power of team work."

"While most of us are familiar with consumer or worker coops, the social co-operative is a bit different. First, it welcomes many types of members – from paid staff and volunteers to service users and family members to social economy investors. While many coops look and feel like their market brethren, with a keen focus on profit and loss, social coops are committed to meeting social goals such as healthcare, eldercare, social services and workforce integration for former prisoners. They are able to blend market activity with social services provisioning and democratic participation, all in one swoop."

Via june holley

|

Scooped by

Howard Rheingold

May 13, 2014 2:18 PM

|

"A new study suggests that predictable social lives accentuate individual quirks and personal styles in spiders that live in groups....But about 25 arachnid species have swapped the hermit’s hair shirt for a more sociable and cooperative strategy, in which dozens or hundreds of spiders pool their powers to exploit resources that would elude a solo player."

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

![[eBook] The Peeragogy Handbook (Howard Rheingold) | Cooperation Theory & Practice | Scoop.it](https://img.scoop.it/-Zgo8KKMiKwAJbj_c6kkaDl72eJkfbmt4t8yenImKBVvK0kTmF0xjctABnaLJIm9)

I called it "infotention," which is shorter than "cognitive load management," but means the same thing: in response to the tsunami of incoming information, people and organizations need to learn both technical and attentional strategies to manage their ability to eliminate the noise and find the signal.