Your new post is loading...

It's like combining Google Translate with a time machine: - Researchers have unearthed hundreds of thousands of cuneiform tablets, but many remain untranslated.

- Translating an ancient language is a time-intensive process, and only a few hundred experts are qualified to perform it.

- A recent study describes a new AI that produces high-quality translations of ancient texts.

Translation isn’t simply a matter of swapping one word for a corresponding word in another language. A high-quality translation requires the translator to understand how both languages string thoughts together and then use that knowledge to create a translation that maintains the linguistic nuances of the original, which native speakers effortlessly understand. As difficult as that process is, it’s nothing compared to the challenge of translating an ancient language into a modern tongue. These translators must not only resurrect extinct languages from written sources but also have intimate knowledge of how the cultures that produced those sources evolved over centuries. If that weren’t enough, their sources are often fragmented, leaving crucial context lost to the ages. Because of this, the number of people capable of translating languages from antiquity is small, and their best efforts are often outpaced by the volume of texts unearthed by archeologists. Take ancient Akkadian. This early Semitic language is one of the best attested from the ancient world. Hundreds of thousands, by some accounts more than a million, Akkadian texts have been discovered and today lie in museums and universities. Many have even been digitized online. Each one has the potential to teach us about the life, politics, and beliefs of the first civilizations, yet this knowledge remains locked behind the time and manpower necessary to translate them. To help change that, a multidisciplinary team of archaeologists and computer scientists has developed an artificial intelligence that can translate Akkadian almost instantly and unlock the historic record preserved in these 5,000-year-old tablets. Hundreds of thousand of cuneiform tablets are housed in museum and university collections, yet many of these remain untranslated due to how time-intensive the process is and how few people have the expertise to do so. Akkadian lost (and found) Akkadian was the mother tongue of the Akkadian Empire, which arose around 2300 B.C. through the conquests of its founder, Sargon the Great. As a spoken language, Akkadian would eventually split into Assyrian and Babylonian dialects before being completely supplanted by Aramaic early in the first millennium BC. Today, it is a truly extinct language, without even daughter languages to carry on its legacy. As a written language, however, Akkadian proved more enduring. The empire borrowed the cuneiform script of its predecessor, the Sumerian civilization. This writing system used a reed stylus to impress wedge-shaped glyphs into wet clay tablets before baking them (hence the name cuneiform, which literally means “wedge-shaped” in Latin). Even after Aramaic supplanted Akkadian as the common language of the region, scholars continued to write in Akkadian cuneiform into the first century AD — even in antiquity, it seems, scholars and academics were incredibly stubborn. This traditional mindset had an unintended benefit for modern archeologists, too. While cuneiform could be written on papyrus, it was more often scribed onto clay or stone. These materials stand up much better to the fires and floods that ravaged their pithy peers. And while time is cruel to all things — archeologists rarely discover cuneiform tablets in mint condition — this is one reason why Akkadian writing may be so well-attested in the historic record. “Ironically, destructive conflagrations have preserved some of ancient Mesopotamia’s greatest libraries — because they were made of clay. In contrast, all of ancient Egypt’s papyrus libraries have burnt or crumbled to dust, though many individual codices survive,” linguist Steven Roger Fischer writes in A History of Writing. Even with such linguist riches, properly translating these ancient libraries is no small feat. Beyond the challenges already mentioned, the Akkadian language is polyvalent. That is, its cuneiform signs can have several different readings depending on how each one functions in a sentence. There are many reasons for this development, but according to Fischer, one reason the Akkadians never simplified was that they “appeared to be bound to tradition and a self-imposed efficiency.” That traditional mindset led them to continue using Sumerian script for a language very different from Sumerian. As such, translating Akkadian is a two-step process. First, scholars must transliterate the cuneiform signs. That is, they take the cuneiform and rewrite it using the similar-sounding phonetics of the target language. An example most readers will be familiar with is the Arabic word الله, which translates into English as “God” but transliterates as “Allah.” This transliteration is the closest the Latin alphabet can get to producing the word as it sounds in Arabic. Scholars then take their transliteration of the text and translate it into a modern language. Fast-acting AI for instant results As you can imagine, that can be a long and laborious process — one that takes years of training and dedication to learn to do well. To help speed things along, the research team developed a neural machine translation model for Akkadian cuneiform, the same technology under the hood of Google Translate. The team trained the AI model on a sample of cuneiform texts from the Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus and taught it to translate in two distinct ways. First, the AI model learned to translate Akkadian from transliterations of the original texts. It also learned how to translate cuneiform symbols directly. More specifically, it translated Unicode glyphs of cuneiform texts that were generated by another time-saving tool that automatically produces Unicode from an image of an original tablet. The AI model then had to figure out how to handle the nuances of the sample’s various genres — for example, the difference between literary works and administrative letters — as well as how to handle the changes found in cuneiform script over the millennia it was used. The AI model was then tested using the bilingual evaluation understudy 4 (BLEU4), an algorithm used to appraise machine-translated text. In its transliteration to English test, the team’s AI model scored 37.47. In its cuneiform to English test, it scored 36.52. Both scores were above their target baseline and in the range of a high-quality translation. And there was a surprising result: The model was able to reproduce the nuances of each test sentence’s genre. While this wasn’t one of the researcher’s goals, they note in the study that it may open possibilities for uses beyond translation. “In almost every instance, whether the [translation] is proper or not, the genre is recognizable,” the team writes. “A promising future scenario would have the [model] show the user a list of sources on which they based their translations, which would also be particularly useful for scholarly purposes.” The team published their results in the peer-reviewed PNAS Nexus. They also released their research and source code on GitHub at Akkademia. Although clay and stone tablets may stand up better than papyrus to the ravishes of time, they are often still found fragmented and may be missing crucial context.(Credit: homocosmicos / Adobe Stock) The past’s future looks brighter As promising as the initial results are, there is still work to be done. In both cases, some of the test sentences were mistranslated. And like other AI models, this one is prone to hallucinations — moments where the response has no connection to the source. In one instance, the human translator produced the sentence “Why should we (also) conduct the lawsuit before a man from Libbi-Ali?” The AI’s translation: “They are in the Inner City in the Inner City.” (A bit off.) All told, the AI model works best when it is translating short- to medium-length sentences. It also does better with more formulaic genres, like royal decrees and administrative records, than literary genres such as myths, hymns, and prophecies. With more training on a larger dataset, the researchers note in the study, they aim to improve its accuracy. In time, they hope their AI model can act as a virtual assistant to human scholars. The AI can provide the raw translation quickly, while the scholar can refine it with their knowledge of historic languages, cultures, and people. “Hundreds of thousands of clay tablets inscribed in the cuneiform script document the political, social, economic, and scientific history of ancient Mesopotamia. Yet, most of these documents remain untranslated and inaccessible due to their sheer number and limited quantity of experts able to read them,” the team writes in the study. “This is another major step toward the preservation and dissemination of the cultural heritage of ancient Mesopotamia.”

Via Charles Tiayon

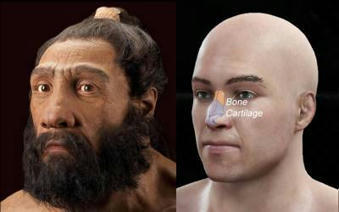

Humans inherited genetic material from Neanderthals that affects the shape of our noses, finds a new study led by UCL researchers. The new Communications Biology study finds that a particular gene, which leads to a taller nose (from top to bottom), may have been the product of natural selection as ancient humans adapted to colder climates after leaving Africa. Co-corresponding author Dr Kaustubh Adhikari (UCL Genetics, Evolution & Environment and The Open University) said: "In the last 15 years, since the Neanderthal genome has been sequenced, we have been able to learn that our own ancestors apparently interbred with Neanderthals, leaving us with little bits of their DNA. "Here, we find that some DNA inherited from Neanderthals influences the shape of our faces. This could have been helpful to our ancestors, as it has been passed down for thousands of generations." The study used data from more than 6,000 volunteers across Latin America, of mixed European, Native American and African ancestry, who are part of the UCL-led CANDELA study, which recruited from Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Mexico and Peru. The researchers compared genetic information from the participants to photographs of their faces -- specifically looking at distances between points on their faces, such as the tip of the nose or the edge of the lips -- to see how different facial traits were associated with the presence of different genetic markers. The researchers newly identified 33 genome regions associated with face shape, 26 of which they were able to replicate in comparisons with data from other ethnicities using participants in east Asia, Europe, or Africa. In one genome region in particular, called ATF3, the researchers found that many people in their study with Native American ancestry (as well as others with east Asian ancestry from another cohort) had genetic material in this gene that was inherited from the Neanderthals, contributing to increased nasal height. They also found that this gene region has signs of natural selection, suggesting that it conferred an advantage for those carrying the genetic material. First author Dr Qing Li (Fudan University) said: "It has long been speculated that the shape of our noses is determined by natural selection; as our noses can help us to regulate the temperature and humidity of the air we breathe in, different shaped noses may be better suited to different climates that our ancestors lived in. The gene we have identified here may have been inherited from Neanderthals to help humans adapt to colder climates as our ancestors moved out of Africa." Co-author Prof. Andres Ruiz-Linares (Fudan University, UCL Genetics, Evolution & Environment, and Aix-Marseille University) added: "Most genetic studies of human diversity have investigated the genes of Europeans; our study's diverse sample of Latin American participants broadens the reach of genetic study findings, helping us to better understand the genetics of all humans." The finding is the second discovery of DNA from archaic humans, distinct from Homo sapiens, affecting our face shape. The same team discovered in a 2021 paper that a gene influencing lip shape was inherited from the ancient Denisovans.*

A recent excavation in Megiddo, Israel, unearthed the earliest example of a particular type of cranial surgery in the Ancient Near East — and potentially one of the oldest examples of leprosy in the world. Archaeologists know that people have practiced cranial trephination, a medical procedure that involves cutting a hole in the skull, for thousands of years. They've turned up evidence that ancient civilizations across the globe, from South America to Africa and beyond, performed the surgery. Now, thanks to a recent excavation at the ancient city of Megiddo, Israel, there's new evidence that one particular type of trephination dates back to at least the late Bronze Age. Rachel Kalisher, a Ph.D. candidate at Brown University's Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, led an analysis of the excavated remains of two upper-class brothers who lived in Megiddo around the 15th century B.C. She found that not long before one of the brothers died, he had undergone a specific type of cranial surgery called angular notched trephination. The procedure involves cutting the scalp, using an instrument with a sharp beveled edge to carve four intersecting lines in the skull, and using leverage to make a square-shaped hole. Kalisher said the trephination is the earliest example of its kind found in the Ancient Near East. "We have evidence that trephination has been this universal, widespread type of surgery for thousands of years," Kalisher said. "But in the Near East, we don't see it so often -- there are only about a dozen examples of trephination in this entire region. My hope is that adding more examples to the scholarly record will deepen our field's understanding of medical care and cultural dynamics in ancient cities in this area." Kalisher's analysis, written in collaboration with scholars in New York, Austria and Israel, was published on Wednesday, Feb. 22, in PLOS ONE.

The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institutet has today decided to award the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Svante Pääbo “for his discoveries concerning the genomes of extinct hominins and human evolution.”

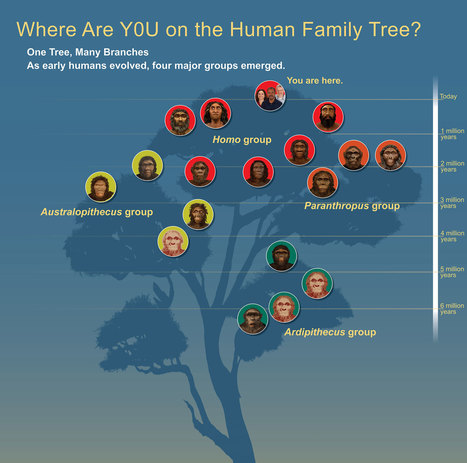

Humanity has always been intrigued by its origins. Where do we come from, and how are we related to those who came before us? What makes us, Homo sapiens, different from other hominins?

Through his pioneering research, Svante Pääbo accomplished something seemingly impossible: sequencing the genome of the Neanderthal, an extinct relative of present-day humans. He also made the sensational discovery of a previously unknown hominin, Denisova. Importantly, Pääbo also found that gene transfer had occurred from these now extinct hominins to Homo sapiens following the migration out of Africa around 70,000 years ago. This ancient flow of genes to present-day humans has physiological relevance today, for example affecting how our immune system reacts to infections.

Pääbo’s seminal research gave rise to an entirely new scientific discipline; paleogenomics. By revealing genetic differences that distinguish all living humans from extinct hominins, his discoveries provide the basis for exploring what makes us uniquely human.

Ancient genomes from the herpes virus that commonly causes lip sores – and currently infects some 3.7 billion people globally – have been uncovered and sequenced for the first time by an international team of scientists led by the University of Cambridge. Latest research suggests that the HSV-1 virus strain behind facial herpes as we know it today arose around five thousand years ago, in the wake of vast Bronze Age migrations into Europe from the Steppe grasslands of Eurasia, and associated population booms that drove rates of transmission. Herpes has a history stretching back millions of years, and forms of the virus infect species from bats to coral. Despite its contemporary prevalence among humans, however, scientists say that ancient examples of HSV-1 were surprisingly hard to find. The authors of the study, published in the journal Science Advances, say the Neolithic flourishing of facial herpes detected in the ancient DNA may have coincided with the advent of a new cultural practice imported from the east: romantic and sexual kissing. “The world has watched COVID-19 mutate at a rapid rate over weeks and months. A virus like herpes evolves on a far grander timescale,” said co-senior author Dr Charlotte Houldcroft, from Cambridge’s Department of Genetics. “Facial herpes hides in its host for life and only transmits through oral contact, so mutations occur slowly over centuries and millennia. We need to do deep time investigations to understand how DNA viruses like this evolve,” she said. “Previously, genetic data for herpes only went back to 1925.” The team managed to hunt down herpes in the remains of four individuals stretching over a thousand-year period, and extract viral DNA from the roots of teeth. Herpes often flares up with mouth infections: at least two of the ancient cadavers had gum disease and a third smoked tobacco. The oldest sample came from an adult male excavated in Russia’s Ural Mountain region, dating from the late Iron Age around 1,500 years ago. Two further samples were local to Cambridge, UK. One a female from an early Anglo-Saxon cemetery a few miles south of the city, dating from 6-7th centuries AD. The other a young adult male from the late 14th century, buried in the grounds of medieval Cambridge’s charitable hospital (later to become St. John’s College), who had suffered appalling dental abscesses. The final sample came from a young adult male excavated in Holland: a fervent clay pipe smoker, most likely massacred by a French attack on his village by the banks of the Rhine in 1672. “We screened ancient DNA samples from around 3,000 archaeological finds and got just four herpes hits,” said co-lead author Dr Meriam Guellil, from Tartu University’s Institute of Genomics. “By comparing ancient DNA with herpes samples from the 20th century, we were able to analyse the differences and estimate a mutation rate, and consequently a timeline for virus evolution,” said co-lead author Dr Lucy van Dorp, from the UCL Genetics Institute. Co-senior author Dr Christiana Scheib, Research Fellow at St. John’s College, University of Cambridge, and Head of the Ancient DNA lab at Tartu University, said: “Every primate species has a form of herpes, so we assume it has been with us since our own species left Africa.” “However, something happened around five thousand years ago that allowed one strain of herpes to overtake all others, possibly an increase in transmissions, which could have been linked to kissing.” The researchers point out that the earliest known record of kissing is a Bronze Age manuscript from South Asia, and suggest the custom – far from universal in human cultures – may have travelled westward with migrations into Europe from Eurasia. In fact, centuries later, the Roman Emperor Tiberius tried to ban kissing at official functions to prevent disease spread, a decree that may have been herpes-related. However, for most of human prehistory, HSV-1 transmission would have been “vertical”: the same strain passing from infected mother to newborn child. Two-thirds of the global population under the age of 50 now carry HSV-1, according to the World Health Organization. For most of us, the occasional lip sores that result are embarrassing and uncomfortable, but in combination with other ailments – sepsis or even COVID-19, for example – the virus can be fatal. In 2018, two women died of HSV-1 infection in the UK following Caesarean births. “Only genetic samples that are hundreds or even thousands of years old will allow us to understand how DNA viruses such as herpes and monkeypox, as well as our own immune systems, are adapting in response to each other,” said Houldcroft. The team would like to trace this hardy primordial disease even deeper through time, to investigate its infection of early hominins. “Neanderthal herpes is my next mountain to climb,” added Scheib. Publisjhed in Science Advances (July 27, 2022): https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abo4435

Via Juan Lama

Modern genetic evidence suggests that statue builders on islands such as Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island, had a shared ancestry. Polynesian voyagers settled islands across a vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean within about 500 years, leaving a genetic trail of the routes that the travelers took, scientists say. Comparisons of present-day Polynesians’ DNA indicate that sea journeys launched from Samoa in western Polynesia headed south and then east, reaching Rarotonga in the Cook Islands by around the year 830. From the mid-1100s to the mid-1300s, people who had traveled farther east to a string of small islands called the Tuamotus fanned out to settle Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island, and several other islands separated by thousands of kilometers on Polynesia’s eastern edge. On each of those islands, the Tuamotu travelers built massive stone statues like the ones Easter Island is famed for. That’s the scenario sketched out in a new study in the Sept. 23 2021 Nature by Stanford University computational biologist Alexander Ioannidis, population geneticist Andrés Moreno-Estrada of the National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity in Irapuato, Mexico, and their colleagues. The new analysis generally aligns with archaeological estimates of human migrations across eastern Polynesia from roughly 900 to 1250. And the study offers an unprecedented look at settlement pathways that zigged and zagged over a distance of more than 5,000 kilometers, the researchers say.

Neanderthal fossils from a cave in Belgium believed to belong to the last survivors of their species ever discovered in Europe are thousands of years older than once thought, a new study said. Previous radiocarbon dating of the remains from the Spy Cave yielded ages as recent as approximately 24,000 years ago, but the new testing pushes the clock back to between 44,200 to 40,600 years ago. The research appeared in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and was carried out by a team from Belgium, Britain and Germany. Co-lead author Thibaut Deviese from the University of Oxford and Aix-Marseille University told AFP he and colleagues had developed a more robust method to prepare samples, which was better able to exclude contaminants. Having a firm idea of when our closest human relatives disappeared is considered a key first step toward understanding more about their nature and capabilities, as well as why they eventually went extinct while our own ancestors prospered. The new method still relies on radiocarbon dating, long considered the gold standard of archeological dating, but refines the way specimens are collected. All living things absorb carbon from the atmosphere and their food, including the radioactive form carbon-14, which decays over time. Since plants and animals stop absorbing carbon-14 when they die, the amount that remains when they are dated tells us how long ago they lived.

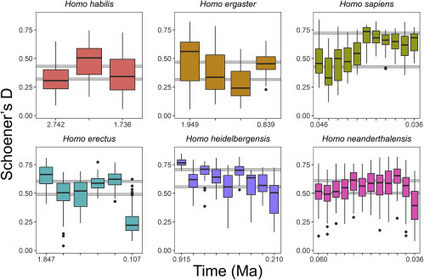

The message of the extinction rebellion protest movement, that human-induced climate change poses a threat to our species' survival, is reawakening consciences worldwide. Climate change is known to have been a major player in the turnover of species throughout the geological record. Were our ancestors, forged through the continually oscillating Pleistocene glacial cycles, not shielded from this danger? To date, the lack of sufficiently detailed and long-timescale climate information and the scarcity of data on early humans have left this question unanswered. By combining a mammoth data collation and analysis with novel paleoclimate modeling, a team of scientists now discovered that, for vanished human species, extinction had a candid, unquestionable climatic drive, which in the case of Neanderthals adds to the effect of competition with ourselves. Notably, Homo sapiens is the only species whose climatic niche was still expanding toward the end of our analysis, when the Neanderthals went extinct. At least six different Homo species populated the World during the latest Pliocene to the Pleistocene. The extinction of all but one of them is currently shrouded in mystery, and no consistent explanation has yet been advanced, despite the enormous importance of the matter. The researchers use a recently implemented past climate emulator and an extensive fossil database spanning 2,754 archaeological records to model climatic niche evolution in Homo. They find statistically robust evidence that the three Homo species representing terminating, independent lineages, H. erectus, H. heidelbergensis, and H. neanderthalensis, lost a significant portion of their climatic niche space just before extinction, with no corresponding reduction in physical range. This reduction coincides with increased vulnerability to climate change. In the case of Neanderthals, the increased extinction risk was probably exacerbated by competition with H. sapiens. This study suggests that climate change was the primary factor in the extinction of Homo species.

Researchers at the Donnelly Centre in Toronto have found that dozens of genes, previously thought to have similar roles across different organisms, are in fact unique to humans and could help explain how our species came to exist. These genes code for a class of proteins known as transcription factors, or TFs, which control gene activity. TFs recognize specific snippets of the DNA code called motifs, and use them as landing sites to bind the DNA and turn genes on or off. Previous research had suggested that TFs which look similar across different organisms also bind similar motifs, even in species as diverse as fruit flies and humans. But a new study from Professor Timothy Hughes' lab, at the Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research, shows that this is not always the case. Writing in the journal Nature Genetics, the researchers describe a new computational method which allowed them to more accurately predict motif sequences each TF binds in many different species. The findings reveal that some sub-classes of TFs are much more functionally diverse than previously thought. "Even between closely related species there's a non-negligible portion of TFs that are likely to bind new sequences," says Sam Lambert, former graduate student in Hughes' lab who did most of the work on the paper and has since moved to the University of Cambridge for a postdoctoral stint. "This means they are likely to have novel functions by regulating different genes, which may be important for species differences," he says. Even between chimps and humans, whose genomes are 99 per cent identical, there are dozens of TFs which recognize diverse motifs between the two species in a way that would affect expression of hundreds of different genes. "We think these molecular differences could be driving some of the differences between chimps and humans," says Lambert, who won the Jennifer Dorrington Graduate Research Award for outstanding doctoral research at U of T's Faculty of Medicine. To reanalyze motif sequences, Lambert developed new software which looks for structural similarities between the TFs' DNA binding regions that relate to their ability to bind the same or different DNA motifs. If two TFs, from different species, have a similar composition of amino-acids, building blocks of proteins, they probably bind similar motifs. But unlike older methods, which compare these regions as a whole, Lambert's automatically assigns greater value to those amino-acids -- a fraction of the entire region -- which directly contact the DNA. In this case, two TFs may look similar overall, but if they differ in the position of these key amino-acids, they are more likely to bind different motifs. When Lambert compared all TFs across different species and matched to all available motif sequence data, he found that many human TFs recognize different sequences -- and therefore regulate different genes -- than versions of the same proteins in other animals. The finding contradicts earlier research, which stated that almost all of human and fruit fly TFs bind the same motif sequences, and is a call for caution to scientists hoping to draw insights about human TFs by only studying their counterparts in simpler organisms.

There's a new addition to the family tree: an extinct species of human that's been found in the Philippines. It's known as Homo luzonensis, after the site of its discovery on the country's largest island Luzon. Its physical features are a mixture of those found in very ancient human ancestors and in more recent people. That could mean primitive human relatives left Africa and made it all the way to South-East Asia, something not previously thought possible. The find shows that human evolution in the region may have been a highly complicated affair, with three or more human species in the region at around the time our ancestors arrive. One of these species was the diminutive "Hobbit" - Homo floresiensis - which survived on the Indonesian island of Flores until 50,000 years ago. Prof Chris Stringer, from London's Natural History Museum, commented: "After the remarkable finds of the diminutive Homo floresiensis were published in 2004, I said that the experiment in human evolution conducted on Flores could have been repeated on many of the other islands in the region. "That speculation has seemingly been confirmed on the island of Luzon... nearly 3,000km away."

Via Neelima Sinha

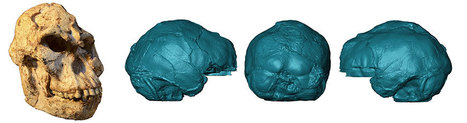

First ever endocast reconstruction of the nearly complete brain of the hominin known as Little Foot reveals a small brain combining ape-like and human-like features. MicroCT scans of the Australopithecus fossil known as Little Foot shows that the brain of this ancient human relative was small and shows features that are similar to our own brain and others that are closer to our ancestor shared with living chimpanzees. While the brain features structures similar to modern humans -- such as an asymmetrical structure and pattern of middle meningeal vessels -- some of its critical areas such as an expanded visual cortex and reduced parietal association cortex points to a condition that is distinct from us. The Australopithecus fossil named Little Foot, an ancient human relative, was excavated over 14 years from the Sterkfontein Caves in South Africa, by Professor Ronald Clarke, from the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits). Its brain endocast was virtually extracted, described and analysed by Wits researcher, Dr Amélie Beaudet, and the Sterkfontein team by using MicroCT scans of the fossil. The scans reveal impressions left on the skull by the brain and the vessels that feed it, along with the shape of the brain. Beaudet's research was released as the first in a series of papers planned for a special issue of this journal on the near-complete "Little Foot" skeleton in the Journal of Human Evolution. "Our ability to reconstruct features of early hominin brains has been limited by the very fragmentary nature of the fossil record. The Little Foot endocast is exceptionally well preserved and relatively complete, allowing us to explore our own origins better than ever before," says Beaudet. The endocast showed that Little Foot's brain was asymmetrical, with a distinct left occipital petalia. Brain asymmetry is essential for lateralisation of brain function. Asymmetry occurs in humans and living apes, as well as in other younger hominin endocasts. Little Foot now shows us that this brain asymmetry was present at a very early date (from 3.67 million years ago), and supports suggestions that it was probably present in the last common ancestor of hominins and other great apes.

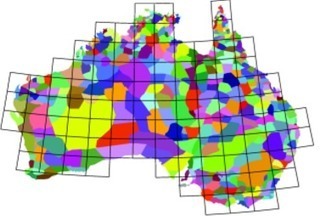

A team of international researchers, led by Colorado State University's Michael Gavin, have taken a first step in answering fundamental questions about human diversity. Humans collectively speak nearly 7,000 languages. But these languages are not spread evenly across the globe. Why do humans speak so many languages, and why are there so many languages in some places and so few in others? In a new study published in Global Ecology and Biogeography, the team was the first to use a form of simulation modeling to study the processes that shape language diversity patterns. Researchers tested the approach in Australia, and the model estimated 406 languages on the continent; the actual number of indigenous languages is 407. The team - which includes linguists, geographers, ecologists, anthropologists and evolutionary biologists based in the United States, Brazil, Germany, Canada, and Sweden - adapted a form of modeling first created by ecologists to study the processes shaping species diversity. The researchers began with a grid on a blank map. The computer model placed a population of people in one cell on the grid and then used a series of simple rules that defined how the population grew, spread across the map, and divided into separate populations speaking different languages.

New archaeological research from The Australian National University (ANU) has found that Homo erectus, an extinct species of primitive humans, went extinct in part because they were 'lazy'. An archaeological excavation of ancient human populations in the Arabian Peninsula during the Early Stone Age, found that Homo erectus used 'least-effort strategies' for tool making and collecting resources. This 'laziness' paired with an inability to adapt to a changing climate likely played a role in the species going extinct, according to lead researcher Dr. Ceri Shipton of the ANU School of Culture, History and Language. "They really don't seem to have been pushing themselves," Dr. Shipton said. "I don't get the sense they were explorers looking over the horizon. They didn't have that same sense of wonder that we have." Dr. Shipton said this was evident in the way the species made their stone tools and collected resources. "To make their stone tools they would use whatever rocks they could find lying around their camp, which were mostly of comparatively low quality to what later stone tool makers used," he said. "At the site we looked at there was a big rocky outcrop of quality stone just a short distance away up a small hill. But rather than walk up the hill they would just use whatever bits had rolled down and were lying at the bottom. When we looked at the rocky outcrop there were no signs of any activity, no artefacts and no quarrying of the stone. They knew it was there, but because they had enough adequate resources they seem to have thought, 'why bother?'". This is in contrast to the stone tool makers of later periods, including early Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, who were climbing mountains to find good quality stone and transporting it over long distances. Dr. Shipton said a failure to progress technologically, as their environment dried out into a desert, also contributed to the population's demise. "Not only were they lazy, but they were also very conservative," Dr. Shipton said. "The sediment samples showed the environment around them was changing, but they were doing the exact same things with their tools. There was no progression at all, and their tools are never very far from these now dry river beds. I think in the end the environment just got too dry for them."

|

An international research team led by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, has for the first time successfully isolated ancient human DNA from a Paleolithic artefact: a pierced deer tooth discovered in Denisova Cave in southern Siberia. To preserve the integrity of the artefact, they developed a new, nondestructive method for isolating DNA from ancient bones and teeth. From the DNA retrieved they were able to reconstruct a precise genetic profile of the woman who used or wore the pendant, as well as of the deer from which the tooth was taken. Genetic dates obtained for the DNA from both the woman and the deer show that the pendant was made between 19,000 and 25,000 years ago. The tooth remains fully intact after analysis, providing testimony to a new era in ancient DNA research, in which it may become possible to directly identify the users of ornaments and tools produced in the deep past. Pierced deer tooth discovered from Denisova Cave in southern Siberia that yielded ancient human DNA. Artefacts made of stone, bones or teeth provide important insights into the subsistence strategies of early humans, their behavior and culture. However, until now it has been difficult to attribute these artefacts to specific individuals, since burials and grave goods were very rare in the Palaeolithic. This has limited the possibilities of drawing conclusions about, for example, division of labor or the social roles of individuals during this period. In order to directly link cultural objects to specific individuals and thus gain deeper insights into Paleolithic societies, an international, interdisciplinary research team, led by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, has developed a novel, non-destructive method for DNA isolation from bones and teeth. Although they are generally rarer than stone tools, the scientists focused specifically on artefacts made from skeletal elements, because these are more porous and are therefore more likely to retain DNA present in skin cells, sweat and other body fluids. A new DNA extraction method Lead author Elena Essel working in the clean laboratory on the pierced deer tooth discovered from Denisova Cave. Before the team could work with real artefacts, they first had to ensure that the precious objects would not be damaged. “The surface structure of Paleolithic bone and tooth artefacts provides important information about their production and use. Therefore, preserving the integrity of the artefacts, including microstructures on their surface, was a top priority” says Marie Soressi, an archaeologist from the University of Leiden who supervised the work together with Matthias Meyer, a Max Planck geneticist. The team tested the influence of various chemicals on the surface structure of archaeological bone and tooth pieces and developed a non-destructive phosphate-based method for DNA extraction. “One could say we have created a washing machine for ancient artifacts within our clean laboratory," explains Elena Essel, the lead author of the study who developed the method. "By washing the artifacts at temperatures of up to 90°C, we are able to extract DNA from the wash waters, while keeping the artifacts intact.”

Scientists have made groundbreaking progress in characterizing the fraction of human DNA that varies between individuals. For more than 20 years, scientists have relied on the human reference genome, a consensus genetic sequence, as a standard against which to compare other genetic data. Used in countless studies, the reference genome has made it possible to identify genes implicated in specific diseases and trace the evolution of human traits, among other things. But it has always been a flawed tool. One of its biggest problems is that about 70 percent of its data came from a single man of predominantly African-European background whose DNA was sequenced during the Human Genome Project, the first effort to capture all of a person's DNA. As a result, it can tell us little about the 0.2 to one percent of genetic sequence that makes each of the seven billion people on this planet different from each other, creating an inherent bias in biomedical data believed to be responsible for some of the health disparities affecting patients today. Many genetic variants found in non-European populations, for instance, aren't represented in the reference genome at all. For years, researchers have called for a resource more inclusive of human diversity with which to diagnose diseases and guide medical treatments. Now scientists with the Human Pangenome Reference Consortium have made groundbreaking progress in characterizing the fraction of human DNA that varies between individuals. As they recently published in Nature, they have assembled genomic sequences of 47 people from around the world into a so-called pangenome in which more than 99 percent of each sequence is rendered with high accuracy. Layered upon each other, these sequences revealed nearly 120 million DNA base pairs that were previously unseen. While it's still a work in progress, the pangenome is public and can be used by scientists around the world as a new standard human genome reference, says The Rockefeller University's Erich D. Jarvis, one of the primary investigators. "This complex genomic collection represents significantly more accurate human genetic diversity than has ever been captured before," he says. "With a greater breadth and depth of genetic data at their disposal, and greater quality of genome assemblies, researchers can refine their understanding of the link between genes and disease traits, and accelerate clinical research." Sourcing diversity Completed in 2003, the first draft of the human genome was relatively imprecise, but it became sharper over the years thanks to filled-in gaps, corrected errors, and advancing sequencing technology. Another milestone was reached last year, when the final eight percent of the genome -- mainly tightly coiled DNA that doesn't code for protein and repetitive DNA regions -- was finally sequenced. Despite this progress, the reference genome remained imperfect, especially with respect to the critical 0.2 to one percent of DNA representing diversity. The Human Pangenome Reference Consortium (HPRC), a government-funded collaboration between more than a dozen research institutions in the United States and Europe, was launched in 2019 to address this problem. At the time, Jarvis, one of the consortium's leaders, was honing advanced sequencing and computational methods through the Vertebrate Genomes Project, which aims to sequence all 70,000 vertebrate species. His and other collaborating labs decided to apply these advances for high-quality diploid genome assemblies to revealing the variation within a single vertebrate: Homo sapiens. To collect a diversity of samples, the researchers turned to the 1000 Genomes Project, a public database of sequenced human genomes that includes more than 2500 individuals representing 26 geographically and ethnically varied populations. Most of the samples come from Africa, home to the planet's largest human diversity. "In many other large human genome diversity projects, the scientists selected mostly European samples," Jarvis says. "We made a purposeful effort to do the opposite. We were trying to counteract the biases of the past." It's likely that gene variants that could inform our knowledge of both common and rare diseases can be found among these populations.

The cellular differences between these species may illuminate steps in their evolution and how those differences can be implicated in disorders, such as autism and intellectual disabilities, seen in humans. While the physical differences between humans and non-human primates are quite distinct, a new study reveals their brains may be remarkably similar. And yet, the smallest changes may make big differences in developmental and psychiatric disorders. Understanding the molecular differences that make the human brain distinct can help researchers study disruptions in its development. A new study, published recently in the journal Science by a team including University of Wisconsin-Madison neuroscience professor Andre Sousa, investigates the differences and similarities of cells in the prefrontal cortex -- the frontmost region of the brain, an area that plays a central role in higher cognitive functions -- between humans and non-human primates such as chimpanzees, Rhesus macaques and marmosets. The cellular differences between these species may illuminate steps in their evolution and how those differences can be implicated in disorders, such as autism and intellectual disabilities, seen in humans. Sousa, who studies the developmental biology of the brain at UW-Madison's Waisman Center, decided to start by studying and categorizing the cells in the prefrontal cortex in partnership with the Yale University lab where he worked as a postdoctoral researcher. "We are profiling the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex because it is particularly interesting. This cortical area only exists in primates. It doesn't exist in other species," Sousa says. "It has been associated with several relevant functions in terms of high cognition, like working memory. It has also been implicated in several neuropsychiatric disorders. So, we decided to do this study to understand what is unique about humans in this brain region." Sousa and his lab collected genetic information from more than 600,000 prefrontal cortex cells from tissue samples from humans, chimpanzees, macaques and marmosets. They analyzed that data to categorize the cells into types and determine the differences in similar cells across species. Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of the cells were fairly comparable. "Most of the cells are actually very similar because these species are relatively close evolutionarily," Sousa says. Sousa and his collaborators found five cell types in the prefrontal cortex that were not present in all four of the species. They also found differences in the abundancies of certain cell types as well as diversity among similar cell populations across species. When comparing a chimpanzee to a human the differences seem huge -- from their physical appearances down to the capabilities of their brains. But at the cellular and genetic level, at least in the prefrontal cortex, the similarities are many and the dissimilarities sparing. "Our lab really wants to know what is unique about the human brain. Obviously from this study and our previous work, most of it is actually the same, at least among primates," Sousa says.

Most linguistics scholars today agree that many of the world’s modern languages share a common forebear. Indeed, this notion lines up perfectly with the sudden appearance of behaviorally modern humans, as they are referred to by geneticists and archaeologists, some 50,000 years ago. Where experts disagree, however, is how language has developed since then.

While many linguists posit that development of sentence structure has been a relatively haphazard process, an unlikely collaboration between a Stanford linguist and a Nobel Prize-winning physicist provides proof of a more linear evolution of language. Merritt Ruhlen, a lecturer in Anthropology at Stanford, and his longtime collaborator Murray Gell-Mann, a founder and Distinguished Professor of the Santa Fe Institute, have mapped the evolution of word order in a paper titled "The Origin and Evolution of Word Order," published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Drawing on a sample of 2,135 of the world’s known languages, they have created a phylogenetic Language Tree, and through it show that sentence structure in the first modern languages followed a subject-object-verb (SOV) order, still evident in many modern languages such as Japanese. With groundbreaking evidence that points to a continuous evolution of language, the scholars provide new insight into how our ancestors may have communicated.

To highlight the significance of such findings, it is first necessary to demonstrate word order in action: In the English language, the common sentence will see the verb follow the subject, and the object follow the verb. Thus, the sentence: “The man reads the book” would be described as having a SVO (subject-verb-object) order. In Japanese, however, the verb follows the object, which itself follows the subject, to produce an SOV word order. It is for this reason that if we were to use Google Translate to decipher the Japanese for: “The man reads the book”, our screen would show us something resembling: “The man the book reads”.

The work of Ruhlen and Gell-Mann demonstrates that such differences did not occur by chance. Using their Language Tree, the authors show not only that SOV was the original word order but, moreover, that word order evolution has since been a largely unidirectional process whenever it has occurred.

Tying Sentence Structure To Migration Patterns

Modern humans first appeared 200,000 years ago, Ruhlen explains, but their social, technological and linguistic capabilities were largely evocative of their predecessors, the Neanderthals. “It was only about 50,000 years ago that major changes occurred by which these humans became not just anatomically modern, but behaviorally modern.” Detail of the geographical distribution of the 12 language families of the world, in an illustration produced by Gell-Mann and Ruhlen.Along with technological innovations, such as the creation of tools from materials other than rock, art and fishing, came the development of fully modern language.

“We can trace the source of all modern languages today to this period,” says Ruhlen. “And it is our argument that the languages of this period were characterized by an SOV word order.” Changes that saw the emergence of other word orders only truly began about 20,000 years ago, says the scholar, as a result of human global migration out of Africa. These migrations allowed the original SOV word order to change into the other five possible word orders at different times in different places.

The origins of the deadly Black Death have been discovered more than 600 years after it entered the human population, scientists have said. The medieval, bubonic plague was first recorded in the 14th century and was the start of a near 500-year-long wave of killer diseases termed the Second Plague Pandemic. The Black Death killed millions and was considered one of the largest infectious disease catastrophes in human history. Despite years of research, the geographic and chronological origin of the disease remained a mystery. But now researchers believe the Black Death first originated in North Kyrgyzstan in the late 1330s. The team, from Scotland’s University of Stirling and Germany’s Max Planck Institute and University of Tubingen, analysed ancient DNA (aDNA) taken from the teeth of skeletons discovered in cemeteries near Lake Issyk Kul in the Tian Shan region of Kyrgyzstan. They were drawn to these sites after identifying a huge spike in the number of burials there in 1338 and 1339, according to University of Stirling historian Dr Philip Slavin, who helped make the discovery. The team found the cemeteries, at Kara-Djigach and Burana, had already been excavated in the late 1880s, with about 30 skeletons taken from the graves, but were able to trace them and analyse DNA taken from the teeth of seven individuals. The sequencing, which determines the DNA structure, showed three individuals carried Yersinia pestis, a bacterium which is linked to the beginning of the Black Death outbreak before it arrived in Europe. ‘Our study puts to rest one of the biggest and most fascinating questions in history and determines when and where the single most notorious and infamous killer of humans began,’ Dr Slavin said.

A near-perfectly preserved ancient human fossil known as the Harbin cranium sits in the Geoscience Museum in Hebei GEO University. The largest of known Homo skulls, scientists now say this skull represents a newly discovered human species named Homo longi or "Dragon Man." Their findings, appearing in three papers publishing June 25 in the journal The Innovation, suggest that the Homo longi lineage may be our closest relatives -- and has the potential to reshape our understanding of human evolution. "The Harbin fossil is one of the most complete human cranial fossils in the world," says author Qiang Ji, a professor of paleontology of Hebei GEO University. "This fossil preserved many morphological details that are critical for understanding the evolution of the Homo genus and the origin of Homo sapiens." The cranium was reportedly discovered in the 1930s in Harbin City of the Heilongjiang province of China. The massive skull could hold a brain comparable in size to modern humans' but had larger, almost square eye sockets, thick brow ridges, a wide mouth, and oversized teeth. "While it shows typical archaic human features, the Harbin cranium presents a mosaic combination of primitive and derived characters setting itself apart from all the other previously-named Homo species," says Ji, leading to its new species designation of Homo longi. Scientists believe the cranium came from a male individual, approximately 50 years old, living in a forested, floodplain environment as part of a small community. "Like Homo sapiens, they hunted mammals and birds, and gathered fruits and vegetables, and perhaps even caught fish," remarks author Xijun Ni, a professor of primatology and paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Hebei GEO University. Given that the Harbin individual was likely very large in size as well as the location where the skull was found, researchers suggest H. longi may have been adapted for harsh environments, allowing them to disperse throughout Asia. Using a series of geochemical analyses, Ji, Ni, and their team dated the Harbin fossil to at least 146,000 years, placing it in the Middle Pleistocene, a dynamic era of human species migration. They hypothesize that H. longi and H. sapiens could have encountered each other during this era.

Carved artifacts excavated from Tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge suggest now-extinct hominids made barbed bone points long before humans did, researchers say. A type of bone tool generally thought to have been invented by Stone Age humans got its start among hominids that lived hundreds of thousands of years before Homo sapiens evolved, a new study concludes. A set of 52 previously excavated but little-studied animal bones from East Africa’s Olduvai Gorge includes the world’s oldest known barbed bone point, an implement probably crafted by now-extinct Homo erectus at least 800,000 years ago, researchers say. Made from a piece of a large animal’s rib, the artifact features three curved barbs and a carved tip, the team reports in the November Journal of Human Evolution. Among the Olduvai bones, biological anthropologist Michael Pante of Colorado State University in Fort Collins and colleagues identified five other tools from more than 800,000 years ago as probable choppers, hammering tools or hammering platforms. The previous oldest barbed bone points were from a central African site and dated to around 90,000 years ago (SN: 4/29/95), and were assumed to reflect a toolmaking ingenuity exclusive to Homo sapiens. Those implements include carved rings around the base of the tools where wooden shafts were presumably attached. Barbed bone points found at H. sapiens sites were likely used to catch fish and perhaps to hunt large land prey. The Olduvai Gorge barbed bone point, which had not been completed, shows no signs of having been attached to a handle or shaft. Ways in which H. erectus used the implement are unclear, Pante and his colleagues say. This find and four of the other bone implements date to at least 800,000 years ago, based on their original positions below Olduvai sediment that records a known reversal of Earth’s magnetic field about 781,000 years ago. Another bone artifact dates to roughly 1.7 million years ago, the researchers say.

Four fossilized monkey teeth discovered deep in the Peruvian Amazon provide new evidence that more than one group of ancient primates journeyed across the Atlantic Ocean from Africa, according to new USC research just published in the journal Science. The teeth are from a newly discovered species belonging to an extinct family of African primates known as parapithecids. Fossils discovered at the same site in Peru had earlier offered the first proof that South American monkeys evolved from African primates.

The monkeys are believed to have made the more than 900-mile trip on floating rafts of vegetation that broke off from coastlines, possibly during a storm. “This is a completely unique discovery,“ said Erik Seiffert, PhD, the study’s lead author and Professor of Clinical Integrative Anatomical Sciences at Keck School of Medicine of USC. “It shows that in addition to the New World monkeys and a group of rodents known as caviomorphs – there is this third lineage of mammals that somehow made this very improbable transatlantic journey to get from Africa to South America.”

Researchers have named the extinct monkey Ucayalipithecus perdita. The name comes from Ucayali, the area of the Peruvian Amazon where the teeth were found, pithikos, the Greek word for monkey and perdita, the Latin word for lost.

The people who lived at Huseby-Kiev in western Sweden 10,000 years ago made their living by hunting and fishing. That doesn't sound surprising until you consider that this was a landscape that had, until recently, been covered by ice sheets 4km (2.5 miles) thick. How they occupied the re-emerging landscape is a bit of a mystery. We don't know much about who they actually were, where they came from, or how they made their way into Sweden as the ice receded. In the 1990s, archaeologists recovered a few chewed-up lumps of birch bark pitch, some of which still held fingerprints and tooth marks left behind from millennia ago. Using this ancient chewing gum, archaeologist Natalija Kashuba of Uppsala University recently recovered DNA from two women and one man who had lived, worked, and apparently chewed gum on the shores of ancient Sweden. That means we can now link DNA from ancient people to their artifacts, and that's a big clue about how people migrated into Scandinavia after the Ice Age. When Kashuba and her colleagues compared the DNA from all three pieces of chewing gum to databases of ancient DNA from other sites, it turned out that the two women and the man from Huseby-Kiev were closely related to the Scandinavian hunter-gatherer group—but their genomes looked more like Mesolithic people from western Europe than from Russia. It's the first time archaeologists have found Scandinavian hunter-gatherer DNA clearly linked with stone tools, and it shows that people in Scandinavia 10,000 years ago were already using the newer eastern European method of pressure-flaking. It also shows that the spread of the new technology wasn't just carried by people from eastern Europe. The two groups were trading ideas, not just genes. On a smaller scale, the DNA samples in the three unassuming lumps of pitch reveal something about the lives and culture of people 10,000 years ago. The tooth marks in the gum came from deciduous teeth (which most people call baby teeth), suggesting that making stone tools wasn't strictly adult work. And two of the three genomes were genetically female, which suggests that tool-making also wasn't a gender-specific job. As DNA sequencing technology improves, archaeologists are finding ancient DNA in surprising places. Earlier this year, the stem of a clay pipe revealed the genome of an enslaved woman who once lived in Maryland. Kashuba and her colleagues say that gums, resins, and similar materials from around the world may also be good sources of ancient DNA, even in places where few human bones have managed to preserve DNA from the distant past. They also suggest that these materials may hold proteins and other molecules which could offer clues about ancient people's diets and microbiomes.

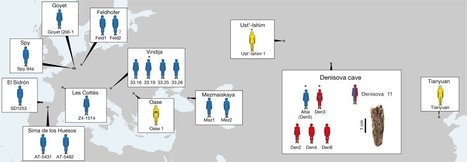

A recent study used machine learning technology to analyze eight leading models of human origins and evolution, and the program identified evidence in the human genome of a “ghost population” of human ancestors. The analysis suggests that a previously unknown and long-extinct group of hominins interbred with Homo sapiens in Asia and Oceania somewhere along the long, winding road of human evolutionary history, leaving behind only fragmented traces in modern human DNA. The study, published in Nature Communications, is one of the first examples of how machine learning can help reveal clues to our own origins. By poring through vast amounts of genomic data left behind in fossilized bones and comparing it with DNA in modern humans, scientists can begin to fill in some of the gaps of our species’ evolutionary history. In this case, the results seem to match paleoanthropology theories that were developed from studying human ancestor fossils found in the ground. The new data suggest that the mysterious hominin was likely descended from an admixture of Neanderthals and Denisovans (who were only identified as a unique species on the human family tree in 2010). Such a species in our evolutionary past would look a lot like the fossil of a 90,000-year-old teenage girl from Siberia's Denisova cave. Her remains were described last summer as the only known example of a first-generation hybrid between the two species, with a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. “It's exactly the kind of individual we expect to find at the origin of this population, however this should not be just a single individual but a whole population,” says study co-author Jaume Bertranpetit, an evolutionary biologist at Barcelona's Pompeu Fabra University.

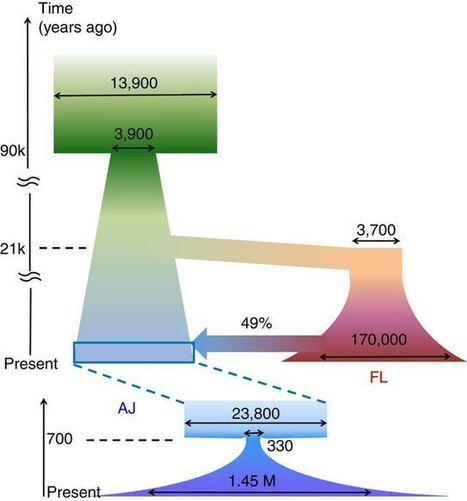

The Ashkenazi Jewish (AJ) population is a genetic isolate close to European and Middle Eastern groups, with genetic diversity patterns conducive to disease mapping. A group of scientists report high-depth sequencing of 128 complete genomes of AJ controls. Compared with European samples, the AJ panel has 47% more novel variants per genome and is eightfold more effective at filtering benign variants out of AJ clinical genomes. Reconstruction of recent AJ history from such segments confirms a recent bottleneck of merely ≈350 individuals. Modeling of ancient histories for AJ and European populations using their joint allele frequency spectrum determines AJ to be an even admixture of European and likely Middle Eastern origins. The split between the two ancestral populations is dated to ≈12–25,000 yrs, suggesting a predominantly Near Eastern source for the repopulation of Europe after the Last Glacial Maximum.

Genetic analysis uncovers a direct descendant of two different groups of early humans. A female who died around 90,000 years ago was half Neanderthal and half Denisovan, according to genome analysis of a bone discovered in a Siberian cave. This is the first time scientists have identified an ancient individual whose parents belonged to distinct human groups. The findings were published on 22 August in Nature1. “To find a first-generation person of mixed ancestry from these groups is absolutely extraordinary,” says population geneticist Pontus Skoglund at the Francis Crick Institute in London. “It’s really great science coupled with a little bit of luck.” The team, led by palaeogeneticists Viviane Slon and Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, conducted the genome analysis on a single bone fragment recovered from Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Russia. This cave lends its name to the ‘Denisovans’, a group of extinct humans first identified on the basis of DNA sequences from the tip of a finger bone discovered [2] there in 2008. The Altai region, and the cave specifically, were also home to Neanderthals. Given the patterns of genetic variation in ancient and modern humans, scientists already knew that Denisovans and Neanderthals must have bred with each other — and with Homo sapiens. But no one had previously found the first-generation offspring from such pairings, and Pääbo says that he questioned the data when his colleagues first shared them. “I thought they must have screwed up something.” Before the discovery of the Neanderthal–Denisovan individual, whom the team has affectionately named Denny, the best evidence for so close an association was found in the DNA of a Homo sapiens specimen who had a Neanderthal ancestor within the previous 4–6 generations [3].

|

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

"It's like combining Google Translate with a time machine.

Translation isn’t simply a matter of swapping one word for a corresponding word in another language. A high-quality translation requires the translator to understand how both languages string thoughts together and then use that knowledge to create a translation that maintains the linguistic nuances of the original, which native speakers effortlessly understand.

As difficult as that process is, it’s nothing compared to the challenge of translating an ancient language into a modern tongue. These translators must not only resurrect extinct languages from written sources but also have intimate knowledge of how the cultures that produced those sources evolved over centuries. If that weren’t enough, their sources are often fragmented, leaving crucial context lost to the ages.

Because of this, the number of people capable of translating languages from antiquity is small, and their best efforts are often outpaced by the volume of texts unearthed by archeologists.

Take ancient Akkadian. This early Semitic language is one of the best attested from the ancient world. Hundreds of thousands, by some accounts more than a million, Akkadian texts have been discovered and today lie in museums and universities. Many have even been digitized online. Each one has the potential to teach us about the life, politics, and beliefs of the first civilizations, yet this knowledge remains locked behind the time and manpower necessary to translate them.

To help change that, a multidisciplinary team of archaeologists and computer scientists has developed an artificial intelligence that can translate Akkadian almost instantly and unlock the historic record preserved in these 5,000-year-old tablets...."

#metaglossia_mundus