Your new post is loading...

About the Group of 77

Establishment: The Group of 77 (G-77) was established on 15 June 1964 by seventy-seven developing countries signatories of the “Joint Declaration of the Seventy-Seven Developing Countries” issued at the end of the first session of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in Geneva. Beginning with the first “Ministerial Meeting of the Group of 77 in Algiers (Algeria) on 10 – 25 October 1967, which adopted the Charter of Algiers”, a permanent institutional structure gradually developed which led to the creation of Chapters of the Group of 77 with Liaison offices in Geneva (UNCTAD), Nairobi (UNEP), Paris (UNESCO), Rome (FAO/IFAD), Vienna (UNIDO), and the Group of 24 (G-24) in Washington, D.C. (IMF and World Bank). Although the members of the G-77 have increased to 134 countries, the original name was retained due to its historic significance.

Aims: The Group of 77 is the largest intergovernmental organization of developing countries in the United Nations, which provides the means for the countries of the South to articulate and promote their collective economic interests and enhance their joint negotiating capacity on all major international economic issues within the United Nations system, and promote South-South cooperation for development. Structure: The functioning and operating modalities of the work of the G-77 in the various Chapters have certain minimal features in common such as a similarity in membership, decision-making and certain operating methods. A Chairman, who acts as its spokesman, coordinates the Group’s action in each Chapter. The Chairmanship, which is the highest political body within the organizational structure of the Group of 77, rotates on a regional basis (between Africa, Asia-Pacific and Latin America and the Caribbean) and is held for one year in all the Chapters. Currently the Republic of South Africa holds the Chairmanship of the Group of 77 in New York for the year 2015. The South Summit is the supreme decision-making body of the Group of 77. The First and the Second South Summits were held in Havana, Cuba, on 10 – 14 April 2000 and in Doha, Qatar, on 12 – 16 June 2005, respectively. In accordance with the principle of geographical rotation, the Third South Summit is due to be held in Africa. The Annual Meeting of the Ministers for Foreign Affairs of the Group of 77 is convened at the beginning of the regular session of the General Assembly of the United Nations in New York. Periodically, Sectoral Ministerial Meetings in preparation for UNCTAD sessions and the General Conferences of UNIDO and UNESCO are convened. Special Ministerial Meetings are also called as needed such as on the occasion of the Group’s 25th anniversary (Caracas, June 1989), 30th anniversary (New York, June 1994), and 40th anniversary (Sao Paulo, Brazil, June 2004). Other Sectoral Ministerial Meetings in various fields of cooperation of interest to the Group are convened, in order to pursue South-South cooperation. Starting in 1995, the Group convened a series of sectoral meetings in the following fields:

- Sectoral Review Meeting of the Group of 77 on Energy, Jakarta, Indonesia, 5 – 7 September 1995;

- Sectoral Meeting of the Group of 77 on Food and Agriculture, Georgetown, Guyana, 15 – 19 January, 1996;

- South-South Conference on Trade, Investment and Finance, San Jose, 13 – 15 January 1997;

- High-level Conference on Subregional and Regional Economic Cooperation among Developing Countries, Bali, Indonesia, 2 – 5 December 1998;

- South-South High-level Conference on Science and Technology of the Group of 77, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 27 – 30 October 2002;

- High-level Conference on South-South Cooperation, Marrakech, Morocco, 16 – 19 December 2003;

- High-level Forum on Trade and Investment, Doha, Qatar, 5 – 6 December 2004;

- Open-ended Intergovernmental Study Group Workshop on the Trade and Development Bank, New York, 2 – 3 May 2005;

- Group of Experts Meeting on Development Platform for the South, Kingston, Jamaica, 29 – 30 August 2005;

- Meeting of the Ministers of Science and Technology of the Member States of the Group of 77, Angra dos Reis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3 September 2006;

- Group of 77 Panel of Eminent Experts on a Development Platform for the South, New York, 18 - 19 October 2007;

- Group of 77 Panel of Eminent Experts on a Development Platform for the South, St. John's, Antigua and Barbuda, 29 - 30 April 2008;

- Ministerial Forum on Water, Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, 23 - 25 February 2009;

- Meeting of the Ministers of Science and Technology of the Member States of the Group of 77 held in Budapest, Hungary, on 4 November 2009 on the occasion of the World Science Forum organized by UNESCO.

In addition to the Sectoral Meetings, the Intergovernmental Follow-up and Coordination Committee on South-South Cooperation (IFCC), which is a plenary body consisting of senior officials, meets once every two years to review the state of implementation of the Caracas Programme of Action (CPA) adopted by the Group of 77 in 1981 and the progress made in the implementation of the outcomes of the South Summits in the field of South-South cooperation.

To date IFCC has held twelve sessions:

IFCC-I (Manila, Philippines, 23 – 28 August 1982); IFCC-II (Tunis, Tunisia, 5 – 10 September 1983); IFCC-III (Cartagena, Colombia, 3 – 8 September 1984); IFCC-IV (Jakarta, Indonesia, 19 – 23 August 1985); IFCC-V (Cairo, Egypt, 18 – 23 August 1986); IFCC-VI (Havana, Cuba, 7 – 12 September 1987): IFCC-VII (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 31 July – 5 August 1989); IFCC-VIII (Panama City, Panama, 30 August – 03 September 1993); IFCC-IX (Manila, Philippines, 8 – 12 February 1996); IFCC-X (Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran, 18 – 23 August 2001); IFCC-XI (Havana, Cuba, 21 – 23 March 2005); IFCC-XII (Yamoussoukro, Côte d'Ivoire, 10-13 June 2008). Finance: The activities of the Group of 77 are financed through contributions by Member States in accordance with the relevant decisions of the First South Summit. Activities:

Besides resolution and decisions initiated by the Group of 77 in the UN General Assembly and its Committees as well as various UN bodies and specialized agencies, the Group of 77 produces joint declarations, action programmes and agreements on development issues. The Group adopted the following declarations/documents since its first Ministerial Meeting held in Algiers in 1967:

- The Charter of Algiers, Algiers, 10 – 25 October 1967;

- Lima Declaration, Lima, 25 October – 7 November 1971;

- Manila Declaration, Manila, 26 January – 7 February 1975;

- Report on the Conference on Economic Cooperation among Developing Countries, Mexico City, 13 – 22 September 1976;

- Arusha Programme for Self-Reliance and Framework for Negotiations, Arusha, 12 – 16 February, 1979;

- Communiqué on the Special Ministerial Meeting of the Group of 77, New York, 11 – 14 March 1980;

- Report on the Ad Hoc Intergovernmental Group on Economic Cooperation among Developing Countries in Continuation of the Ministerial Meeting of the Group of 77, New York, March 1980, and Vienna, 3 – 7 June 1980;

- Communiqué on the Special Ministerial Meeting of the Group of 77, New York, 21 – 22 August 1980;

- The Caracas Programme of Action on Economic Cooperation among Developing Countries, Caracas, 13 – 19 May 1981;

- Ministerial Declaration on the Global System of Trade Preferences among Developing (GSTP), 8 October 1982;

- The Buenos Aires Platform, Buenos Aires, 5 – 9 April 1983;

- Declaration on the Global System of Trade Preferences (GSTP), New Delhi, July 1985;

- Brasilia Declaration on the Launching of the First Round of Negotiations within the Global System of Trade Preferences among Developing Countries, Brasilia, 22 – 23 May 1986;

- The Cairo Declaration on Economic Cooperation among Developing Countries (ECDC), Cairo, 18 – 23 August 1986;

- Havana Declaration, Havana, 20 – 25 April, 1987;

- Agreement on a Global System of Trade Preferences among Developing Countries (GSTP), Belgrade, 11 – 13 April 1988;

- Caracas Declaration on the ccasion of the Twenty-fifth Anniversary of the Group of 77, Caracas, 13 – 23 June 1989;

- Recommendations and conclusions of the Group of Experts on the Review and Evaluation of the Implementation of the Caracas Programme of Action (New York, 5 – 9 August 1991);

- Tehran Declaration, Tehran, 19 – 23 November 1991;

- Tehran Declaration on the Second Round of the Global System of Trade Preferences among Developing Countries (GSTP), Tehran, 21 November 1991;

- Ministerial Declaration adopted on the occasion of the Thirtieth Anniversary of the Group of 77, New York, 24 June 1994;

- Ministerial Statement on “An Agenda for Development”, New York, 24 June 1994;

- Conclusions and recommendations of the Sectoral Review Meeting of the Group of 77 on Energy (Jakarta, Indonesia, 5 – 7 September 1995);

- The Midrand Declaration, Midrand, South Africa, 28 April 1996;

- Conclusions and recommendations of the Sectoral Meeting on Food and Agriculture of the G-77 (Georgetown, Guyana, 15 – 19 January 1996);

- The San Jose Declaration and Plan of Action on South-South Trade, Investment and Finance, San Jose, Costa Rica,13 – 15 January 1997;

- The Bali Declaration and Plan of Action on High-level Meeting on Subregional and Regional Economic Integration, Bali, Indonesia, 2 – 5 December 1998;

- Recommendations and conclusions of the High-level Advisory Meeting on the South Summit (Jakarta, Indonesia, 10 – 11 August 1998);

- The Marrakech Declaration (Marrakech, Morocco,16 September 1999);

- Final Report on the Group of 77 Meeting of Eminent Personalities to advise on the preparations for the First South Summit (Georgetown, Guyana, 6 – 7 December 1999);

- Declaration and the Havana Programme of Action adopted by the First South Summit (Havana, 10 – 14 April 2000);

- Tehran Consensus adopted by IFCC-X (Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran,18 – 23 August 2001);

- Declaration by the Group of 77 and China on the Fourth WTO Ministerial Conference (Doha, Qatar 9 – 14 November 2001);

- Agreed conclusions and recommendations of the Meeting of the High-level Advisory Group of Eminent Personalities and Intellectuals on Globalization and its Impact on Developing Countries: (Geneva, Switzerland, 12 – 14 September 2001);

- The Dubai Declaration for the Promotion of Science and Technology in the South (Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 27 – 30 October 2002);

- Declaration by the Group of 77 and China on the Fifth WTO Ministerial Conference (Cancun, Mexico, 10 – 14 September 2003);

- The Marrakech Declaration on South-South Cooperation and the Marrakech Framework of the Implementation of South-South Cooperation (Marrakech, Morocco, 16 – 19 December 2003);

- The Sao Paulo Declaration (Sao Paulo, Brazil, 11 – 12 June 2004);

- Ministerial Declaration adopted on the occasion of the Fortieth Anniversary of the Group of 77 (Sao Paulo, Brazil, 11 – 12 June 2004);

- Conclusions and recommendations of the Ad-hoc Group on the Performance, Mandates and Operating Modalities of the G-77 Chamber of Commerce and Industry (G-77 CCI) (New York, 3 November and Doha, 3 – 4 December 2004);

- Conclusions and recommendation on the Group of 77 High-level Forum on Trade and Investment (Doha, Qatar, 5 – 6 December 2004);

- Conclusions and recommendations of the Open-ended Intergovernmental Study Group Workshop on the Trade and Development Bank (New York, 2 – 3 May 2005);

- Doha Declaration and Doha Plan of Action adopted by the Second G-77 South Summit (Doha, Qatar, 12 – 16 June 2005);

- Conclusions and recommendations of the Group of Experts Meeting on the Development Platform for the South (Kingston, Jamaica, 29 – 30 August 2005);

- Declaration by the Group of 77 and China in preparation of the Sixth WTO Ministerial Conference (Hong Kong, China, 13 – 18 December 2005).

- Conclusions and Recommendations on the Ministers of Science and Technology of the Members States of the Group of 77 (Angra dos Reis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3 September 2006);

- Yamoussoukro Consensus on South-South Cooperation adopted by the Twelfth Session of the Intergovernmental Follow-up and Coordination Committee on Economic Cooperation among Developing Countries (IFCC-XII) (Yamoussoukro, Côte d'Ivoire, 10 – 13 June 2008);

- Declaration on Water adopted by the First Ministerial Forum on Water of the Group of 77 (Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, 23 – 25 February 2009);

- Declaration "For a new world order for living well" adopted by the Summit of Heads of State and Government on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the Group of 77 (Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Plurinational State of Bolivia, 14-15 June 2014).

The Group of 77 also makes statements at various Main Committees of the General Assembly, ECOSOC and other subsidiary bodies, sponsors and negotiates resolutions and decisions at major conferences and other meetings held under the aegis of the United Nations dealing with international economic cooperation and development as well as the reform of the United Nations.

Furthermore, the Group of 77 sponsors projects on South-South cooperation through funding from the Perez-Guerrero Trust Fund (PGTF) and promotes South-South trade through the Global System of Trade Preferences (GSTP).

The 2015 G-20 Antalya summit will be the tenth annual meeting of the G-20 heads of government. It will be held in Antalya, a southwestern province of Turkey which is home to the country's biggest international sea resort, on 15-16 November 2015. The venue has yet to be determined or announced.

The 2015 G-20 Antalya summit will be the tenth annual meeting of the G-20 heads of government.[1] It will be held in Antalya, a southwestern province of Turkey which is home to the country’s biggest international sea resort, on 15-16 November 2015. The venue has yet to be determined or announced. Turkey officially took over the presidency of the G-20 from Australia in December 1, 2014 and China will preside over the organization in 2016. [2][3] Possible participating leaders Invited guests References

The G33 is a group of developing countries that coordinate on trade and economic issues. It was created in order to help a group of countries that were all facing similar problems.

The G33 is a group of developing countries that coordinate on trade and economic issues. It was created in order to help a group of countries that were all facing similar problems. The G33 has proposed special rules for developing countries at WTO negotiations, like allowing them to continue to restrict access to their agricultural markets. Members

The cyber attack during the Paris G20 Summit refers to an event that took place shortly before the beginning of the G20 Summit held in Paris, France in February 2011.

The cyber attack during the Paris G20 Summit refers to an event that took place shortly before the beginning of the G20 Summit held in Paris, France in February 2011. This summit was a Group of 20 conference held at the level of governance of the finance ministers and central bank governors (as opposed to the 6th G20 summit later that year, held in Cannes and involving the heads of government). Unlike other well-known cyber attacks, such as the 2009 attacks affecting South Korean/American government, news media and financial websites, or the 2007 cyberattacks on Estonia, the attack that took place during the Paris G20 Summit was not a DDoS style attack. Instead, these attacks involved the proliferation of an email with a malware attachment, which permitted access to the infected computer. Cyber attacks in France generally include attacks on websites by DDoS attacks as well as malware. Attacks have so far been to the civil and private sectors instead of the military. Like the UK, Germany and many other European nations, France has been proactive in cyber defence and cyber security in recent years. The White Paper on Defence and National Security proclaimed cyber attacks as "one of the main threats to the national territory" and "made prevention and reaction to cyber attacks a major priority in the organisation of national security".[1] This led to the creation of the French Agency for National Security of Information Systems (ANSSI) in 2009. ANSSI's workforce will be increased to a workforce of 350 by the end of 2013. In comparison, the equivalent English and German departments boast between 500 and 700 people. Attacks in December 2010-January 2011The attacks began in December with an email sent around the French Ministry of Finance. The email's attachment was a 'Trojan Horse' type consisting of a pdf document with embedded malware. Once accessed, the virus infected the computers of some of the government's senior officials as well as forwarding the offensive email on to others. The attack infected approximately 150 of the finance ministry's 170,000 computers. While access to the computers at the highest levels of office of infiltrated departments was successfully blocked, most of the owners of infiltrated computers worked on the G20.[2] The attack was noticed when "strange movements were detected in the e-mail system". Following this, ANSSI monitored the situation for a further several weeks. [3] Reportedly, the intrusion only targeted the exfiltration of G20 documents. Tax and financial information and other sensitive information for individuals, which is also located in the Ministry of Finance's servers, was left alone as it circulates only on an intranet accessible only within the ministry. The attack was reported in news media only after the conclusion of the summit in February 2011, but was discovered a month prior in January. PerpetratorsWhile the nationalities of the hackers are unknown, the operation was "probably led by an Asian country". [4] The head of ANSSI, Patrick Pailloux, said the perpetrators were "determined professionals and organised" although no further identification of the hackers was made.[3] See alsoReferences

Young European Leadership (YEL) is an international non-profit and nonpartisan organization composed of as well as founded by young Europeans. Its core mission is to empower the young generation to shape the future of Europe. Through YEL, young Europeans are able to participate in key decision-making processes and speak-up.

Young European Leadership (YEL)[1] is an international non-profit and nonpartisan organization composed of as well as founded by young Europeans. Its core mission is to empower the young generation to shape the future of Europe. Through YEL, young Europeans are able to participate in key decision-making processes and speak-up. HistoryFollowing the Y8 and Y20 Summits in 2011 – previously called G8 & G20 Youth Summits- held in France, the organization YouthAEGIS has been founded. Its main goal was to recruit the delegates of the European Union for the next editions of the Y8 and Y20 Summits. AEGIS was renamed Young European Leadership in 2012. The new association was legally established in Brussels as an AISBL (international non-profit organization) the year after. ActivitiesYEL is a platform giving the possibility to young Europeans to influence decisions which concern young people in Europe and beyond. Aspiring leaders are brought into the position to speak up, address their concerns, and provide innovative solutions. This is why YEL trains young Europeans in leadership skills such as public speaking or negotiations skills. YEL is also a platform for networking. Young adults connect with each other but also with global decision-makers by participating to the Y8 and Y20 as well as other major European and international events. In this way, young people are ready to face positively and proactively the European crises and the challenges facing our world. Young European CouncilYoung European Leadership organised the Young European Council (YEC) from 20 to 23 October 2014 in Brussels. It gathered students and young professionals from all over Europe to address three challenges: education to employment, digital revolution and technologies, and sustainable development in cities; exchanging with policy-makers from the European institutions and think-tank experts. Youth 8/Youth 20The Y8 and Y20 Summits[2] – formerly G8 and G20 Youth Summits[3] – are international youth conferences gathering young leaders. These Summits are the official youth counterpart to the Group of Eight (G8) and the Group of Twenty (20). The goal of the summits is to allow the young generation to speak up. Young adults are indeed able to provide solutions to the global agenda, promote cross-cultural understanding and build global friendships. The conclusions of the Summits are then passed on to international policy-makers to make the young people heard. This is why the Youth Summits are always scheduled in parallel to the G8 and G20. Host countryCitiesSummitsYear GermanyTurkeyBerlin and IstanbulYouth Summit 7 and Youth Summit Y202015 AustraliaSydneyY202014 UKRussiaLondon and Saint PetersburgY8 [4] & Y20 [5]2013 USAMexico. [6]Washington and PueblaY8 & Y20 [7]2012 FranceParisY8 & Y202011 CanadaVancouverY8 & Y20 [8]2010 Italy[9]MilanoY8 [10]2009 JapanYokohamaY8 [11]2008 Germany[12]BerlinY8 [13][14]2007 RussiaSaint PetersburgY82006 European Council SimulationThe European Council Simulation[15][16] is a simulation[17] of the European Council for young people. The participants can get concrete insight into the European decision-making processes. The different national positions on various issues discussed at the European level such as energy, the question of the Euro or EU-bilateral relations, are covered. Through this exercise, the young adults have the chance to impersonate European leadership, gain extensive experience in negotiation, and have the ability to build strong and multicultural friendships with the other participants. The role of YEL is not only the practical organization of the Council, but also to support the participants to face this experience at the best of their abilities. The participants are also given the chance to discuss with key policy-makers: diplomats and experts and European and International Affairs. European Development DaysThe European Development Days is Europe's forum for international affairs and development cooperation. This initiative is sponsored by the European Commission and its premier goal is to consolidate the general view on development issues and create a unified approach to achieve a more effective international cooperation. During the forum, Heads of State, Nobel Laureates and YEL together with many other participants are present. The international delegation of YEL to the EDD 2013 blended in with 10 delegates, 6 young women, 4 young men, from Croatia, Denmark, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Turkey, and the United States. YEL SocietyThe YEL Society is a unique channel and platform for university students as well as young professionals, involved, or willing to be, in European and global politics. The Young European Leadership Society (YEL Society) believes that young people must be given the chance to design the world they are living in. Through this channel, young leaders can get involved in various projects through which they will acquire leadership skills. OrganisationBoardEuropean and International PartnersIn order to broaden its network and raise visibility on his work, YEL has several partners in Europe and worldwide. European Partners: International Partner: - United Nations Foundation

- The International Diplomatic Engagement Association (The IDEA) [24] YEL is the only supranational member of The International Diplomatic Engagement Association (The IDEA).

The following list of G-20 summits summarizes all Group of 20 conferences held at various different levels: heads of government, finance ministers and central bank governors , employment and labour ministers of the G-20 major economies, and others.

The following list of G-20 summits summarizes all Group of 20 conferences held at various different levels: heads of government, finance ministers and central bank governors , employment and labour ministers of the G-20 major economies, and others. Heads of governmentYear#DatesCountryCityHost leaderRef2008 1st14–15 November United StatesWashington, D.C.George W. Bush[1]2009 2nd2 April United KingdomLondonGordon Brown[1]3rd24–25 September United StatesPittsburghBarack Obama[1]2010 4th26–27 June CanadaTorontoStephen Harper[2]5th11–12 November South KoreaSeoulLee Myung-bak[3]2011 6th3–4 November FranceCannesNicolas Sarkozy[4]2012 7th18–19 June MexicoLos CabosFelipe Calderón[5]2013 8th5–6 September RussiaStrelna, Saint PetersburgVladimir Putin[6][7][8]2014 9th15–16 November AustraliaBrisbaneTony Abbott[6][9]2015 10th15—16 November TurkeyAntalyaAhmet Davutoğlu[6][10]2016 11thNovember ChinaHangzhouXi Jinping[6][10][11]Ministerial-level summitsFinance ministers and central bank governorsLocations in bold text indicate the meeting was concurrent with a G-20 summit. YearLocationDatesNotes1999 Berlin, Germany2000 Montreal, Canada2001 Ottawa, Canada2002 New Delhi, India2003 Morelia, Mexico2004 Berlin, Germany2005 Beijing, China2006 Melbourne, Australia2007 Cape Town, South Africa2008 São Paulo, Brazil2009 Horsham, United KingdomMarch London, United KingdomSeptember St Andrews, United KingdomNovember2010 Incheon, South KoreaFebruary Toronto, CanadaJune Seoul, South KoreaNovember2011 Paris, FranceFebruary Washington, D.C., United StatesApril Washington, D.C., United StatesSeptemberAs part of the annual meeting of the IMF and World Bank [12] Paris, FranceOctober Cannes, FranceNovember2012 Mexico City, MexicoFebruary Washington, D.C., United StatesApril Mexico City, MexicoNovember [13]2013 Moscow, RussiaFebruary [14] Washington, D.C., United StatesAprilPart of the annual meeting of the IMF and World Bank [15] Washington, D.C., United StatesOctoberContinuation of the meeting mentioned above [16]2014 Sydney, AustraliaFebruary Washington, D.C., United StatesApril Cairns, AustraliaSeptember2015 Istanbul, TurkeyFebruary 9-10 [17]Labour and employment ministersB-20 SummitsB-20 summits are summits of business leaders from the G-20 countries. C-20 SummitsC-20 summits are summits of civil society delegates from the G-20 countries. T-20 SummitsT20 Summits are summits of the think tanks from the G-20 countries. Trade and Investment Promotion SummitsSee also

The 2014 G20 Brisbane summit was the ninth meeting of the G20 heads of government. It was held in Brisbane, the capital city of Queensland, Australia, on 15-16 November 2014. The hosting venue was the Brisbane Convention & Exhibition Centre at South Brisbane. The event was the largest ever peacetime police operation in Australia.

The 2014 G20 Brisbane summit was the ninth meeting of the G20 heads of government.[1] It was held in Brisbane, the capital city of Queensland, Australia, on 15–16 November 2014. The hosting venue was the Brisbane Convention & Exhibition Centre at South Brisbane.[2] The event was the largest ever peacetime police operation in Australia.[3] On 1 December 2013 Brisbane became the official host city for the G20.[4] The City of Brisbane had a public holiday on 14 November 2014.[5] Up to 4,000 delegates were expected to attend with around 2,500 media representatives.[6] The leaders of Mauritania, Myanmar, New Zealand, Senegal, Singapore, and Spain were also invited to this summit.[7] 1. Agenda European leaders expressed their desire to support the recovery as the global economy moves beyond the global financial crisis. European Commission President Barroso and European Council President Van Rompuy stressed the importance of coordinated growth strategies as well as finalising agreements on core financial reforms, and actions on tax and anti-corruption. According to Waheguru Pal Singh Sidhu the main objectives of the summit were to "provide strategic priority for growth, financial rebalancing and emerging economies, investment and infrastructure, and employment and labour mobility". Professor of international finance law at the University of New South Wales Ross Buckley suggested that the summit should have emphasised the implementation of existing strategies rather than seeking agreement towards reforms. Climate change was not included as a subject for discussion at the summit; Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott stated he did not want the agenda "cluttered" by subjects that would distract from economic growth. Officials from the European Union and United States of America were reported to be unhappy with this decision. At each of the previous summits climate change was included on the agenda. The Australian media stated that Australia will have had a significant effect on the agenda. Mike Callaghan, the director of the G20 Studies Centre at the Lowy Institute for International Policy has stated that if the G20 meeting was to attain significant outcomes it should focus on boosting infrastructure spending, multilateral trading systems and combating Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS).[13] The discussion on tax avoidance had been fueled by a disclosure of confidential tax agreements between more than 340 multinational corporations and Luxembourg (see also Luxembourg Leaks). 2. Preparations The G20 leaders wave on the final day of the forum The Prime Minister of Australia, at the time of the 2011 G20 Cannes summit, Julia Gillard, was asked to have Australia host the 2014 summit. Brisbane was selected over Sydney because the city was better equipped to cater for a significant increase in plane arrivals and the Sydney Convention and Exhibition Centre would be undertaking renovations at the time. The Parliament of Queensland passed the G20 (Safety and Security) Act 2013 on 29 October 2013. The event involved a complex security operation. Event organisers needed to ensure that appropriate security measures were in place to protect visitors, while minimising disruptions to inner-city residents and businesses. About 6,000 police from Queensland, wider Australia and New Zealand ensured security at the event, and more than 600 volunteers provided assistance at the summit. Roads between the central business district and the Brisbane Airport were temporarily closed. Around 1,500 security specialists including interstate and overseas personnel together with thousands of Queensland police made patrols. Public transport services were reduced in the central business district and surrounding suburbs. One wing in a major Brisbane hospital was reserved for the exclusive use of world leaders during the summit. A secure, government wireless network was required for public safety communications during the summit. Telstra established the network in Brisbane, the Gold Coast and Cairns before the event and later continued rolling it out across South East Queensland. The Australian Government rented 16 bombproof Mercedes Benz S-Guard limousines specially for the summit at a cost of AU$1.8 million. Some world leaders however, including Barack Obama and Vladimir Putin planned to bring their own vehicles. 800 people were involved in a security exercise, which tested responses to security issues, crowd management and transport for over 10 hours on 6 October 2014. Actors portraying delegates were used, which involved a mock world leader arriving from a Qantas Boeing 737-800 at Brisbane International Airport into a 13-vehicle motorcade consisting of police motorbikes, police cars, sedans, vans, an SUV and a ute, which travelled from the airport to a Brisbane hotel. The cost of hosting the event was estimated at around AU$400 million. 3. Associated meetings G20 finance ministers and central bank governors met several times in 2014. Sydney hosted a meeting on 21–23 February 2014 followed by a meeting in Cairns, Queensland in September 2014. At the September meeting participating countries agreed to automatically exchange tax information to reduce tax evasion.[26] Canberra hosted a meeting for G20 finance and central bank deputies in 2014.[27] The Youth 20 Summit was the official G20 youth event held in Sydney in July 2014.[28] A meeting of G20 trade ministers took place in Sydney during July, and the annual G20 Labour and Employment Ministerial Meeting was held in Melbourne during September. Officials-levels meetings of public servants took place throughout the year to prepare for the ministerial meetings.[29] 4. Security measures Police boats patrolling the Brisbane River on the day before the summit A declared area took effect from 8 November with several restricted areas which were to be fenced and guarded by police.[30] Freedom of movement for ordinary citizens was restricted. According to the G20 (Safety and Security) Regulation 2014[31] and article 12 of the G20 (Safety and Security) Act 2013,[32] the restricted areas could have been changed at the Police Commissioner's or the Minister's request at any time during the proceedings. Residents living in these areas had to have a security clearance performed, and their car given a security pass. Residents not receiving a security clearance were forced to leave the area, but were paid accommodation expenses. The G20 legislation suspended important civil liberties, including the absolute right to arrest without warrant, in addition to the Police Powers Act 2000, to detain people without charge, to predispose the courts into not giving arrested individuals bail, extensive searches of the person without warrant,[33] including strip searches, and the banning of common household items carried in public. Officers had the backing of increased penalties when lawful directions are not followed. The Peaceful Assembly Act of 1992 was suspended during the G20 meeting dates. Size of placards were strictly regulated, as was permission to protest, and the location of protests. Legal observers were in force to observe the use of police power during this time.[34] Heavy fines were enforceable due to the legislation. Most offenses carried between 50 and 100 penalty units worth of fines. A penalty unit in 2014 is $110.[35] 5. Attendance This meeting was the first time an Argentine President could not be in attendance; Cristina Fernández de Kirchner was ill, and so was represented by Economy Minister Axel Kicillof. 6. Issues involving Russia Opinion was divided both in Australia and elsewhere on whether Russian President Vladimir Putin should have been allowed to attend the G20 summit, following Russia's response to the crash of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 as well as pro-Russian actions in Ukraine earlier in the year.[36] Australia's foreign minister, Julie Bishop, approached other G20 countries about banning Putin from the meeting, and stated that this consultation found that there was not the necessary consensus to exclude him.[37] A poll taken in July 2014 found 49% of Australians did not think Putin should be allowed to attend.[38] It was confirmed in September that Putin would attend, with Abbott stating that "The G20 is an international gathering that operates by consensus – it's not Australia's right to say yes or no to individual members of the G20".[39] In November 2014, Russia sent a fleet of warships into international waters off the coast of Australia to accompany Putin's visit. The fleet consisted of Varyag, Marshal Shaposhnikov, a salvage and rescue tug, and a replenishment oiler. Australia responded by sending Stuart and Parramatta, as well as a P-3 Orion surveillance plane, to monitor the Russians.[40][41] Although Russia had previously sent warships to accompany presidential attendance at international summits, the size of fleet and the lack of official notification to the host country made this an unprecedented move.[42] At the private leaders' retreat, held shortly before the official opening of the summit, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper told Russian President Vladimir Putin "I guess I'll shake your hand but I have only one thing to say to you: You need to get out of Ukraine." The incident occurred as Putin approached Harper and a group of G20 leaders and extended his hand toward Harper. After the event was over, a spokesman for the Russian delegation said Putin's response was: "That's impossible because we are not there."[43] Participating leaders Invited guests Outcomes Following the summit, the G20 leaders released a joint communique summarising the points of agreement between them. This focused on economic concerns, highlighting plans to increase global economic growth, create jobs, increase trade and reduce poverty. The communique sets out a goal of increasing economic growth by an extra 2% through commitments made at the summit, and of increasing infrastructure investment through the creation of a four-year infrastructure hub, linking government, private sector, development banks and interested international organisations. The communique also addressed the stability of global systems, mentioning measures to reduce risk in financial systems, improve the stability of banks, make international taxation arrangements fairer, reduce corruption and strengthen global institutions. Although the communique largely focused on economic concerns, other topics such as energy supply, climate change and the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa were also discussed.[44]

The Group of Twenty (also known as the G-20 or G20) is an international forum for the governments and central bank governors from 20 major economies. The members, shown highlighted on the map at right, include 19 individual countries- Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States-along with the European Union (EU).

Invitees Typically, several participants that are not permanent members of the G20 are extended invitations to participate in the summits. Each year, the Chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations; the Chair of the African Union and a representative of the New Partnership for Africa's Development are invited in their capacities as leaders of their organisations and as heads of government of their home states.[46] Additionally, the leaders of the Financial Stability Board, the International Labour Organization, the International Monetary Fund, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the United Nations, the World Bank Group and the World Trade Organization are invited and participate in pre-summit planning within the policy purview of their respective organisation.[47] Spain is a permanent non-member invitee.[46] Other invitees are chosen by the host country, usually one or two countries from its own region.[46] For example, South Korea invited Singapore. International organisations which have been invited in the past include the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Eurasian Economic Community (EAEC), the European Central Bank (ECB), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the Global Governance Group (3G) and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Previously, the Netherlands had a similar status to Spain while the rotating presidency of the Council of the European Union would also receive an invitation, but only in that capacity and not as their own state's leader (such as the Czech premiers Mirek Topolánek and Jan Fischer during the 2009 summits). As of 2014, leaders from the following nations have been invited to the G20 summits: Benin, Brunei, Cambodia, Chile, Colombia, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Kazakhstan, Malawi, Mauritania, Myanmar, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Senegal, Singapore, Spain, Switzerland, Thailand, the United Arab Emirates and Vietnam.[46] Permanent guest invitationsInviteeOfficeholderStateOfficial titleAfrican Union (AU)Robert Mugabe ZimbabwePresidentAssociation of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)Najib Razak MalaysiaPrime MinisterLê Lương Minh VietnamSecretary-GeneralFinancial Stability Board (FSB)Mark Carney United Kingdom

CanadaChairpersonInternational Labour Organization (ILO)Guy Ryder United KingdomDirector GeneralInternational Monetary Fund (IMF)Christine Lagarde FranceManaging DirectorKingdom of Spain (ESP)Mariano Rajoy SpainPrime MinisterNew Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD)Macky Sall SenegalPresidentOrganisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)José Ángel Gurría MexicoSecretary-GeneralUnited Nations (UN)Ban Ki-moon South KoreaSecretary-GeneralWorld Bank Group (WBG)Jim Yong Kim United StatesPresidentWorld Trade Organization (WTO)Roberto Azevêdo BrazilDirector General

The Group of Twenty (also known as the G-20 or G20) is an international forum for the governments and central bank governors from 20 major economies. The members, shown highlighted on the map at right, include 19 individual countries- Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States-along with the European Union (EU).

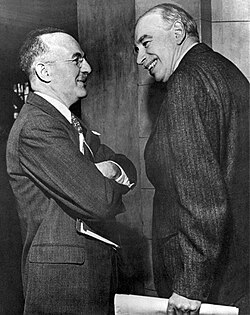

History The G-20 is the latest in a series of post-World War II initiatives aimed at international coordination of economic policy, which include institutions such as the "Bretton Woods twins", the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and what is now the World Trade Organization.[7] The G-20 superseded the G33 (which had itself superseded the G22), and was foreshadowed at the Cologne Summit of the G7 in June 1999, but was only formally established at the G7 Finance Ministers' meeting on 26 September 1999. The inaugural meeting took place on 15–16 December 1999 in Berlin. Canadian finance minister Paul Martin was chosen to be the first chairman and German finance minister Hans Eichel hosted the inaugural meeting.[8] According to researchers at the Brookings Institution, the group was founded primarily at the initiative of Eichel, who was also concurrently chair of the G7. However, some sources identify the G-20 as a joint creation of Germany and the United States.[9][10] According to University of Toronto professor John Kirton, the membership of the G-20 was decided by Eichel's deputy Caio Koch-Weser and then US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers' deputy Timothy Geithner. In Kirton's book G20 Governance for a Globalised World, he claims that: "Geithner and Koch-Weser went down the list of countries saying, Canada in, Spain out, South Africa in, Nigeria and Egypt out, and so on; they sent their list to the other G7 finance ministries; and the invitations to the first meeting went out."[11]

Though the G-20's primary focus is global economic governance, the themes of its summits vary from year to year. For example, the theme of the 2006 G-20 meeting was "Building and Sustaining Prosperity". The issues discussed included domestic reforms to achieve "sustained growth", global energy and resource commodity markets, reform of the World Bank and IMF, and the impact of demographic changes due to an aging world population. Trevor A. Manuel, the South African Minister of Finance, was the chairperson of the G-20 when South Africa hosted the Secretariat in 2007. Guido Mantega, Brazil's Minister of Finance, was the chairperson of the G-20 in 2008; Brazil proposed dialogue on competition in financial markets, clean energy and economic development and fiscal elements of growth and development. In a statement following a meeting of G7 finance ministers on 11 October 2008, US President George W. Bush stated that the next meeting of the G-20 would be important in finding solutions to the burgeoning economic crisis of 2008. An initiative by French President Nicolas Sarkozy and British Prime Minister Gordon Brown led to a special meeting of the G-20, a G-20 Leaders Summit on Financial Markets and the World Economy, on 15 November 2008.[12] Spain and the Netherlands were included in the summit by French invitation. Despite lacking any formal ability to enforce rules, the G-20's prominent membership gives it a strong input on global policy. However, there remain disputes over the legitimacy of the G-20,[13] and criticisms of its organisation and the efficacy of its declarations.[14]

Summits

The G-20 Summit was created as a response both to the financial crisis of 2007–2010 and to a growing recognition that key emerging countries were not adequately included in the core of global economic discussion and governance. The G-20 Summits of heads of state or government were held in addition to the G-20 Meetings of Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, who continued to meet to prepare the leaders' summit and implement their decisions. After the 2008 debut summit in Washington, D.C., G-20 leaders met twice a year in London and Pittsburgh in 2009, Toronto and Seoul in 2010.[15] Since 2011, when France chaired and hosted the G-20, the summits have been held only once a year.[16] Russia chaired and hosted the summit in 2013;[17] while the summit was held in Australia in 2014,[18] with Turkey hosting it in 2015.[19] A number of other ministerial-level G20 meetings have been held since 2010. Agriculture ministerial meetings were conducted in 2011 and 2012; meetings of foreign ministers were held in 2012 and 2013; trade ministers met in 2012 and 2014 and employment ministerial meetings have taken place annually since 2010.[20] Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop, as host of the then-upcoming G20 meeting, proposed on 19 March 2014 to ban Russia over its role in the 2014 Crimean crisis.[21] She was reminded on 24 March by a communique of the BRICS foreign ministers that "The Ministers noted with concern, the recent media statement on the forthcoming G20 Summit to be held in Brisbane in November 2014. The custodianship of the G20 belongs to all Member States equally and no one Member State can unilaterally determine its nature and character."[22

G-20 leaders' chair rotation

To decide which member nation gets to chair the G-20 leaders' meeting for a given year, all 19 sovereign nations are assigned to one of five different groupings. Each group holds a maximum of four nations. This system has been in place since 2010, when South Korea, which is in Group 5, held the G-20 chair. Australia, the host of the 2014 G-20 summit, is in Group 1. Turkey, which will host the 2015 summit, is in Group 2. The table below lists the nations' groupings:[32]

The Group of Seven (G7, formerly G8) is a governmental forum of leading advanced economies in the world. It was originally formed by six leading industrial countries and subsequently extended with two additional members, one of which, Russia, is suspended.[1][2][3][4] Since 2014, the G8 in effect comprises seven nations and the European Union as the eighth member. The forum originated with a 1975 summit hosted by France that brought together representatives of six governments: France, West Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, thus leading to the name Group of Six or G6. The summit became known as the Group of Seven or G7 in 1976 with the addition of Canada. The G7 is composed of the seven wealthiest developed countries on earth (by national net wealth or by GDP, and it remained active even during the period of the G8. Russia was added to the group from 1998 to 2014, which then became known as the G8. The European Union was represented within the G8 since the 1980s but could not host or chair summits. The 40th summit was the first time the European Union was able to host and chair a summit.

The first summit, with six countries participating (France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States), was prompted by concerns about the global economy and oil supplies. It was held in 1975 in Rambouillet, France. Summits have focused on the global economy, international security, social development and issues of the day.

Preparatory meetings The host country organizes several preparatory meetings before the summit. G7 leaders’ personal representatives, known as Sherpas, attend these meetings to discuss potential agenda items. The Sherpas, usually high-ranking government officials, communicate directly with each other throughout the year. In 2015, Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s Sherpa for the Elmau Summit is Peter M. Boehm, Associate Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs. What happens at the Summit? The Summit is a rare chance for the democratically elected Leaders of the G7 countries to meet, discuss common challenges, and decide on some common responses. Future Summits 2016 - Japan

2017 - Italy

2018 - Canada G7 Summit Locations and Dates1975-2014 4-5 June 2014 - Brussels (Belgium) 24 March 2014 – The Hague, The Netherlands Between 1997–2013, the G7 met in G8 format as Russia was invited to join the group in recognition of the economic and democratic reforms it had undertaken at that time. In 2014, Russia’s violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity led to suspension of participation in the G8, and a return to G7 format. 17-18 June 2013 - Lough Erne (United Kingdom)

18-19 May 2012 - Camp David (United States of America)

26-27 May 2011 - Deauville (France)

25-26 June 2010 - Muskoka (Canada)

8-10 July 2009 - L'Aquila (Italy)

7-9 July 2008 - Hokkaido Toyako (Japan)

6-8 June 2007 - Heiligendamm (Germany)

15-17 July 2006 - St Petersburg (Russia)

6-8 July 2005 - Gleneagles, Scotland (United Kingdom)

8-10 June 2004 - Sea Island, Georgia (United States of America)

1-3 June 2003 - Evian (France)

26-27 June 2002 - Kananaskis (Canada)

20-22 July 2001 - Genoa (Italy)

21-23 July 2000 - Okinawa (Japan)

18-20 June 1999 - Okinawa (Japan)

15-17 May 1998 - Birmingham (United Kingdom)

20-22 June 1997 - Denver (United States of America)

27-29 June 1996 - Lyon (France)

19-20 April 1996 - Moscow (Russia) - Nuclear Safety and Security Summit

15-17 June 1995 - Halifax (Canada)

8-10 July 1994 - Naples (Italy)

7-9 July 1993 - Tokyo (Japan)

6-8 July 1992 - Munich (Germany)

15-17 July 1991 - London (United Kingdom)

9-11 July 1990 - Houston (United States of America)

14-16 July 1989 - Paris (France)

19-21 June 1988 - Toronto (Canada)

8-10 June 1987 - Venice (Italy)

4-6 May 1986 - Tokyo (Japan)

2-4 May 1985 - Bonn (Germany)

7-9 June 1984 - London (United Kingdom)

28-30 May 1983 – Williamsburg (United States of America)

4-6 June 1982 – Versailles (France)

19-21 July 1981 - Ottawa (Canada)

22-23 June 1980 - Venice (Italy)

28-29 June 1979 - Tokyo (Japan)

16-17 July 1978 - Bonn (Germany)

6-8 May 1977 - London (United Kingdom)

27-28 June 1976 - Puerto Rico (United States of America)

15-17 November 1975 - Rambouillet (France) Membership One can access information about Canada's relations with G7 partners by selecting country from the list below: - Date Modified:

- 2015-01-13

The 39th G8 summit was held on 17-18 June 2013, at the Lough Erne Resort, a five-star hotel and golf resort on the shore of Lough Erne in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom. It was the sixth G8 summit to be held in the United Kingdom.

The 39th G8 summit was held on 17–18 June 2013, at the Lough Erne Resort, a five-star hotel and golf resort on the shore of Lough Erne in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom.[1] It was the sixth G8 summit to be held in the United Kingdom. The earlier G8 summits hosted by the United Kingdom were held at London (1977, 1984, 1991), Birmingham (1998) and Gleneagles (2005). The official theme of the summit was tax evasion and transparency. However, the Syrian civil war dominated the discussions. A seven-point plan on Syria was agreed after much debate. Other agreements included a way to automate the sharing of tax information, new rules for mining companies, and a pledge to end payments for kidnap victim releases. The United States and the European Union agreed to begin talks towards a broad trade agreement. OverviewThe Group of Six (G6), started in 1975, was an unofficial forum which brought together the heads of the richest industrialized countries: France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States. This select few became the Group of Seven (G7) starting in 1976 when Canada joined. The Group of Eight was formed with the addition of Russia in 1997.[2] In addition, the President of the European Commission has been formally included in summits since 1981.[3] The summits were not meant to be linked formally with wider international institutions; and in fact, a mild rebellion against the stiff formality of other international meetings was a part of the genesis of cooperation between France's President Giscard d'Estaing and Germany's Chancellor Helmut Schmidt as they conceived the initial summit of the Group of Six in 1975.[4] The G8 summits during the twenty-first century have inspired widespread debates, protests and demonstrations; and the two- or three-day event becomes more than the sum of its parts, elevating the participants, the issues and the venue as focal points for activist pressure.[5] The current form of the G8 is being evaluated. Some reports attribute resistance to the relatively smaller powers such as the UK, Canada and Japan, who are said to perceive a dilution of their global stature. Alternately, a larger forum for global governance may be more reflective of the present multi-polar world.[6] The forum is in a process of transformation by expanded membership and by other changes.[7] Location and local dangersThe date and location of the summit was announced by British Prime Minister David Cameron in November 2012.[1][8] According to Mark Simpson, the BBC's Ireland Correspondent, the British Government chose Fermanagh for two main reasons: history and geography.[1] Since the formation of Northern Ireland in 1921, there has been tension and violence between its two main communities. The unionist/loyalist community (who are mostly Protestant) generally want Northern Ireland to remain within the United Kingdom, while the Irish nationalist/republican community (who are mostly Catholic) generally want it to leave the United Kingdom and join a united Ireland. From the late 1960s until the late 1990s, these two communities and the British state were involved in an ethno-nationalist conflict known as the Troubles, in which over 3,500 people were killed. A peace process led to the Belfast Agreement and ceasefires by the paramilitary groups involved (such as the republican Provisional IRA, the loyalist Ulster Volunteer Force). The Conservative Party government of David Cameron is a unionist one. By holding it in Northern Ireland, Cameron "will hope it sends the message to the rest of the world that the peace process has worked and normality has returned".[1] The second reason is geography. G8 summits have always drawn large demonstrations, but Fermanagh's geography will make it hard for protesters. Much of the Lough Erne Resort is surrounded by water and almost all of the roads within 30 miles are single carriageway.[1] Lodges at Lough Erne Resort Some have criticized the decision to hold the summit in Northern Ireland, due to ongoing protests and small-scale violence by both republicans and loyalists.[9] Since the Provisional IRA called a ceasefire at the end of the Troubles, dissident republican splinter groups have continued its paramilitary campaign. The main groups involved in this low-intensity campaign are the Real IRA, Continuity IRA and Óglaigh na hÉireann. Security sources expected that these groups would try to launch an attack during the summit, which "would hijack global headlines".[10] On 23 March 2013, a car bomb was defused 16 miles (26 km) from the Lough Erne Resort. Republican group Óglaigh na hÉireann said it had planned to detonate it at the hotel but had to abort the attack.[11] There was also the possibility of disruption and violence involving loyalists. The summit took place during the marching season, when Protestant and loyalist groups (such as the Orange Order) hold parades throughout Northern Ireland.[12] This is a tense time in Northern Ireland and it often results in clashes between the two main communities. Since December 2012, loyalists have been holding daily street protests. They have been protesting against the decision to lessen the number of days the Union Jack flies from Belfast City Hall. Some of these protests have sparked rioting. Protesters discussed holding a Union Jack protest at the G8 summit.[13] Security preparationsPolice Service of Northern Ireland armoured Land Rovers (in 2011). The Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) mounted a huge security operation in County Fermanagh, at Belfast International Airport (where many of the G8 leaders arrived) and in Belfast. The police operation involved about 8,000 officers: 4,500 from the PSNI and 3,500 who were drafted in from other parts of the UK. They were also trained in PSNI riot tactics and to drive its armoured vehicles.[14] The Lough Erne Resort was surrounded by a four-mile long metal fence and razor wire.[15] Lower Lough Erne was made off-limits to the general public[16] and an air corridor between Belfast and the Resort was made a no-fly zone during the summit. British Army Chinook and Merlin helicopters were used to escort political leaders and their entourages to and from the Resort.[17] The PSNI also bought surveillance drones to help police the summit, while in Belfast, landmark buildings were guarded round-the-clock.[18] The PSNI said it would "uphold the right to peaceful protest" but that there were to be "consequences" for any protesters who broke the law. More than 100 cells at Northern Ireland's high-security prison, Maghaberry, were set aside for any violent protesters[14] and a temporary cell block was built in Omagh.[19] Anyone arrested during protests at or near the resort were taken to the Omagh holding centre to be questioned and held before going to court.[19] Sixteen judges were put on standby to preside over special court sittings.[19] PSNI superintendent Paula Hilman said "We will be able to have a detained person processed, interviewed if required, charged, and appear before the court in a very short time, in a matter of hours".[19] Some protest groups feared that the PSNI would use the dissident republican threat as an excuse for repressive measures against protesters.[14] The Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) planned to send human rights observers to monitor the PSNI. CAJ deputy director Daniel Holder said his organization was "firmly and absolutely opposed to the use of plastic bullets", which he said had been fired on 12 occasions in Northern Ireland over the past year.[14] In the Republic of Ireland, almost 1,000 officers from the Garda Síochána mounted a security operation along the border.[20] Eight temporary border checkpoints were manned by Garda units backed up by the Irish Army.[21] The Garda's elite tactical team, the Emergency Response Unit (ERU), and the special operations forces from the Defence Forces, the Army Ranger Wing (ARW), were deployed on land and water to secure the border from unauthorised crossings.[22] Some of the delegations attending the summit stayed in the Republic,[21] and protesters announced their intention to hold demonstrations in Dublin. Like in Northern Ireland, a special court had also been set up in the Republic to deal with protesters who were arrested there. The court operated day and night at Cloverhill Prison in Dublin. Suspects remanded in custody would then be moved through a tunnel from the courthouse to the adjoining jail.[23] Meanwhile, American warships were deployed off the coast of County Donegal and in the Irish Sea as security measures.[24] The cost of the summit is expected to be about £60 million. The Northern Ireland Government will pay £6 million and the British Government will pay for the rest.[25] ParticipantsG8 leaders (left to right): Herman Van Rompuy, Enrico Letta, Stephen Harper, François Hollande, Barack Obama, David Cameron, Vladimir Putin, Angela Merkel, José Manuel Barroso and Shinzō Abe. Barack Obama with Vladimir Putin at the summit. The attendees included the leaders of the eight G8 member states, as well as representatives of the European Union. A number of national leaders, and heads of international organizations, are traditionally invited to attend the summit and to participate in some, but not all, G8 summit activities. The 39th G8 summit was the first and only summit for Italian Prime Minister Enrico Letta. Core G8 participantsCore G8 members Host state and leader are shown in bold text.MemberRepresented byTitle CanadaStephen HarperPrime MinisterFranceFrançois HollandePresidentGermanyAngela MerkelChancellorItalyEnrico LettaPrime MinisterJapanShinzō AbePrime MinisterRussiaVladimir PutinPresidentUnited KingdomDavid CameronPrime MinisterUnited StatesBarack ObamaPresidentEuropean UnionJosé Manuel BarrosoCommission PresidentHerman Van RompuyCouncil President- Invited leaders

AgendaTransatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership meeting at the G8 summit on 17 June 2013. Officially, tax evasion and transparency were the themes of the summit. However, the Syrian civil war dominated the agenda. According to Cameron, it was also the most difficult issue addressed. A declaration signed by the eight nations outlines a seven-point plan for Syria. It calls for more humanitarian aid, "[maximizing] diplomatic pressure" aiming for peace talks, backing a transitional government, "[learning] the lessons of Iraq" by maintaining Syria public institutions, ridding the country of terrorists, condemning the use of chemical weapons "by anyone", and instilling a new non-sectarian government.[29] They called for UN investigations into the use of chemical weapons with the promise that whoever had used them would be punished. Although Syrian President Bashar al-Assad was not mentioned by name in the declaration, Cameron said it was "unthinkable" that he would remain in power.[29] Agreements were also reached on global tax evasion and data sharing. The G8 nations agreed to tight rules on corporate tax that sometimes allow companies to shift income from one nation to another to avoid taxes.[29] They agreed that shell companies should have to disclose their true owners, and that it should be easy for any G8 nation to obtain this information. Going forward, corporate and individual tax information will be shared automatically to help detect tax fraud and evasion.[30] The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development was assigned to gather data on how multinationals evade taxes.[29] The G8 nations agreed that oil, gas, and mining companies should report payments from the government, and likewise that the government should report the resources they obtain.[29] The measure was aimed at helping developing countries collect taxes from first-world companies operating in their territories.[30] A declaration to stop paying ransom demands for kidnap victims was also signed.[29] During the summit the United States and the European Union (EU) announced they would enter into trade deal negotiations. Canadian PM Stephen Harper said the EU and Canada were close to wrapping up a similar deal after years of negotiations which should not be affected by the US-EU announcement.[29] Harper and Obama also had an informal meeting to discuss border relations during the summit. Harper said they discussed "a range of Canada-US issues that you would expect, obviously the Keystone pipeline."[29]

The Group of Seven ( G7, formerly G8) is a governmental forum of leading advanced economies in the world. It was originally formed by six leading industrial countries and subsequently extended with two additional members, one of which, Russia, is suspended. Since 2014, the G8 in effect comprises seven nations and the European Union as the eighth member.

Youth 8 Summit

The Y8 Summit or simply Y8, formerly known as the G8 Youth Summit[106] is the youth counterpart to the G8 summit.[107] The first summit to use the name Y8 took place in May 2012 in Puebla, Mexico, alongside the Youth G8 that took place in Washington, D.C. the same year. The Y8 Summit brings together young leaders from G8 nations and the European Union to facilitate discussions of international affairs, promote cross-cultural understanding, and build global friendships. The conference closely follows the formal negotiation procedures of the G8 Summit.[108] The Y8 Summit represents the innovative voice of young adults between the age of 18 and 35. The delegates jointly come up with a consensus-based[109] written statement in the end, the Final Communiqué.[110] This document is subsequently presented to G8 leaders in order to inspire positive change.[111] The Y8 Summit is organised annually by a global network of youth-led organisations called The IDEA (The International Diplomatic Engagement Association).[112] The organisations undertake the selection processes for their respective national delegations, while the hosting country is responsible for organising the summit. Now, several youth associations are supporting and getting involved in the project. For instance, every year, the Young European Leadership association is recruiting and sending EU Delegates. The goal of the Y8 Summit is to bring together young people from around the world to allow the voices and opinions of young generations to be heard and to encourage them to take part in global decision-making processes.[113][114] - The Y8 Summit 2014 in Moscow was suspended due to the suspension of Russia from the G8.

See also

|

The group was founded on June 15, 1964, by the "Joint Declaration of the Seventy-Seven Countries" issued at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). The first major meeting was in Algiers in 1967, where the Charter of Algiers was adopted and the basis for permanent institutional structures was begun.

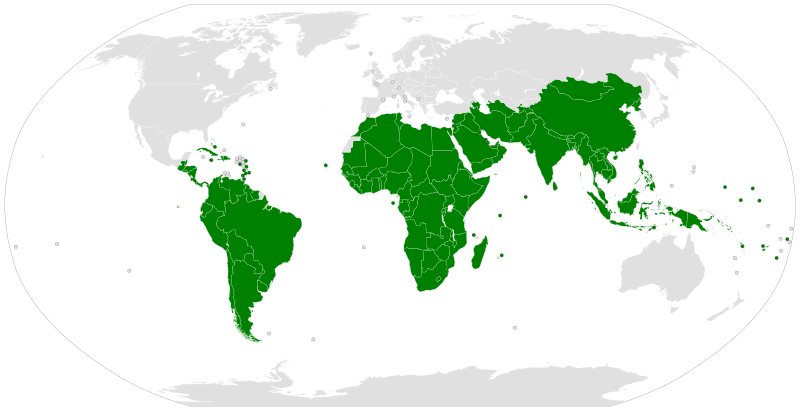

The Group of 77 at the United Nations is a loose coalition of developing nations, designed to promote its members' collective economic interests and create an enhanced joint negotiating capacity in the United Nations.[1] There were 77 founding members of the organization, but by November 2013 the organization had since expanded to 134 member countries.[2] South Africa holds the Chairmanship for 2015. The group was founded on June 15, 1964, by the "Joint Declaration of the Seventy-Seven Countries" issued at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).[3] The first major meeting was in Algiers in 1967, where the Charter of Algiers was adopted and the basis for permanent institutional structures was begun. There are Chapters of the Group of 77 in Rome (FAO), Vienna (UNIDO), Paris (UNESCO), Nairobi (UNEP) and the Group of 24 in Washington, D.C. (International Monetary Fund and World Bank). MembersAs of 2014, the group comprises all of UN members (along with the Palestinian Authority) – excluding the following: - All Council of Europe members (with the exception of Bosnia and Herzegovina);

- All Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development members (with the exception of Chile);

- All Commonwealth of Independent States (full) members (with the exception of Tajikistan);

- Two Pacific microstates: Palau and Tuvalu.

On the map, founding and currently participating members (as of 2008) are shown in dark green, while founding members that have since left the organization are shown in light green. Currently participating members that joined after the foundation of the Group are shown in medium green. Group of 77 countries as of 2008 Member nations are listed below. The years in parenthesis represent the year/s a country has presided. Countries listed in bold are also members of the G-24. See the official list of G-77 members. Current founding members- Afghanistan

- Algeria (1981–1982, 1994, 2009, 2012)

- Argentina (2011)

- Benin

- Bolivia (1990)

- Brazil

- Burkina Faso

- Cambodia

- Cameroon

- Central African Republic

- Chad

- Chile

- Colombia (1992)

- Democratic Republic of the Congo (Kinshasa)

- Congo (Brazzaville)

- Costa Rica (1996)

- Cuba

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt (1972–1973, 1984–1985)

- El Salvador

- Ethiopia

- Gabon

- Ghana (1991)

- Guatemala (1987)

- Guinea

- Haiti

- Honduras

- India (1970–1971, 1979–1980)

- Indonesia (1998)

- Iran (1973–1974, 2001)

- Iraq

- Jamaica (1977–1978, 2005)

- Jordan

- Kenya

- Kuwait

- Laos

- Lebanon

- Liberia

- Libya

- Madagascar (1975–1976)

- Malaysia (1989)

- Mali

- Mauritania

- Morocco (2003)

- Myanmar

- Nepal

- Nicaragua

- Niger

- Nigeria (2000)

- Pakistan (1976–1977, 1992, 2007)

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru (1971–1972)

- Philippines (1995)

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Senegal

- Sierra Leone

- Somalia

- Sri Lanka

- Sudan (2009)

- Syria

- Tanzania (1997)

- Thailand

- Togo

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Tunisia (1978–1979, 1988)

- Uganda

- Uruguay

- Venezuela (1980–1981, 2002)

- Vietnam

- Yemen (2010)

Other current members- Angola

- Antigua and Barbuda (2008)

- Bahamas

- Bahrain

- Bangladesh (1982–1983)

- Barbados

- Belize

- Bhutan

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Botswana

- Brunei

- Burundi

- Cape Verde

- China

- Comoros

- Ivory Coast

- Djibouti

- Dominica

- Equatorial Guinea

- Eritrea

- Fiji

- Gambia

- Grenada

- Guinea-Bissau

- Guyana (1999)

- Kiribati

- Lesotho

- Malawi

- Maldives

- Marshall Islands

- Mauritius

- Micronesia

- Mongolia

- Mozambique

- Namibia

- North Korea

- Nauru

- Oman

- Palestine

- Papua New Guinea

- Qatar

- Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Samoa

- São Tomé and Príncipe

- Seychelles

- Singapore

- Solomon Islands

- South Africa (2006)

- South Sudan

- Suriname

- Swaziland

- Tajikistan

- Timor-Leste

- Tonga

- Turkmenistan

- United Arab Emirates

- Vanuatu

- Zambia

- Zimbabwe

Former membersPresiding countries of the G-77 since 1970. Colors show the number of times a country has held the position. Yellow = once; orange = twice; red = thrice. Countries in grey are yet to hold the position. - New Zealand signed the original "Joint Declaration of the Developing Countries" in October 1963, but pulled out of the group before the formation of the G-77 in 1964 (it joined the OECD in 1973).

- Mexico was a founding member, but left the Group after joining the OECD in 1994. It had presided over the group in 1973–1974, 1983–1984; however, it is still a member of G-24.

- South Korea was a founding member, but left the Group after joining the OECD in 1996.

- South Vietnam was a founding member, but left the Group in 1975 when the North Vietnamese captured Saigon.

- Yugoslavia was a founding member; by the late 1990s it was still listed on the membership list, but it was noted that it "cannot participate in the activities of G-77." It was removed from the list in late 2003.[citation needed] It had presided over the group in 1985–1986. Bosnia and Herzegovina is the only part of former Yugoslavia that is currently in G-77.

- Cyprus was a founding member, but was no longer listed on the official membership list after its accession to the EU in 2004.

- Malta was admitted to the Group in 1976, but was no longer listed on the official membership list after its accession to the EU in 2004.

- Palau joined the Group in 2002, but withdrew in 2004, having decided that it could best pursue its environmental interests through the Alliance of Small Island States.

- Romania was admitted to the Group in 1976, but was no longer listed on the official membership list after its accession to the EU in 2007.

Group of 24G-24 countries. Member nations Observer nations The Group of 24 (G-24) is a chapter of the G-77 that was established in 1971 to coordinate the positions of developing countries on international monetary and development finance issues and to ensure that their interests were adequately represented in negotiations on international monetary matters. The Group of 24, which is officially called the Intergovernmental Group of Twenty-Four on International Monetary Affairs and Development, is not an organ of the International Monetary Fund, but the IMF provides secretariat services for the Group. Its meetings usually take place twice a year, prior to the IMFC and Development Committee meetings, to enable developing country members to discuss agenda items beforehand. Although membership in the G-24 is strictly limited to 24 countries, any member of the G-77 can join discussions (Mexico is the only G-24 member that is not a G-77 member, when it left the G-77 without resigning its G-24 membership). China has been a "special invitee" since the Gabon meetings of 1981. Naglaa El-Ehwany, Minister of International Cooperation, Egypt, is the current chairman of the G-24. See alsoReferencesExternal linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Group of 77.

The examples and perspective in this article Please deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. improve this article and discuss the issue on the talk page.

International monetary systems are sets of internationally agreed rules, conventions and supporting institutions, that facilitate international trade, cross border investment and generally the reallocation of capital between nation states. They provide means of payment acceptable between buyers and sellers of different nationality, including deferred payment. To operate successfully, they need to inspire confidence, to provide sufficient liquidity for fluctuating levels of trade and to provide means by which global imbalances can be corrected. The systems can grow organically as the collective result of numerous individual agreements between international economic factors spread over several decades. Alternatively, they can arise from a single architectural vision as happened at Bretton Woods in 1944.

Historical overview

Throughout history, precious metals such as gold and silver have been used for trade, termed bullion, and since early history the coins of various issuers – generally kingdoms and empires – have been traded. The earliest known records of pre - coinage use of bullion for monetary exchange are from Mesopotamia and Egypt, dating from the third millennium BC.[1] Early money took many forms, apart from bullion; for instance bronze Spade money which became common in Zhou dynasty China in the late 7th century BC. At this time, forms of money were also developed in Lydia, Asia minor, from where its use spread to nearby Greek cities and later to the rest of the world.[1] Sometimes formal monetary systems have been imposed by regional rulers. For example scholars have tentatively suggested that the ruler Servius Tullius created a primitive monetary system in the archaic period of what was to become the Roman Republic. Tullius reigned in the sixth century BC - several centuries before Rome is believed to have developed a formal coinage system.[2]