Deaf mice have been able to hear a tiny whisper after being given a "landmark" gene therapy by US scientists. They say restoring near-normal hearing in the animals paves the way for similar treatments for people "in the near future".

Studies, published in Nature Biotechnology, corrected errors that led to the sound-sensing hairs in the ear becoming defective. The researchers used a synthetic virus to nip in and correct the defect.

"It's unprecedented, this is the first time we've seen this level of hearing restoration," said researcher Dr Jeffrey Holt, from Boston Children's Hospital.

About half of all forms of deafness are due to an error in the instructions for life - DNA. In the experiments at Boston Children's Hospital, Massachusetts Eye and Ear and Harvard Medical School, the mice had a genetic disorder called Usher syndrome. It means there are inaccurate instructions for building microscopic hairs inside the ear.

In healthy ears, sets of outer hair cells magnify sound waves and inner hair cells then convert sounds to electrical signals that go to the brain. The hairs normally form these neat V-shaped rows.

Sound waves produce the sensation of hearing by vibrating hair-like structures on the inner ear’s sensory hair cells. But how this mechanical motion gets converted into electrical signals that go to our brains has long been a mystery.

Scientists have believed some undiscovered protein is involved. Such proteins have been identified for taste, smell and sight, but the protein required for hearing has been elusive. In part, that’s because it’s hard to get enough cells from the inner ear to study – they’re embedded deep in the cochlea.

“People have been looking for more than 30 years,” says Jeffrey Holt of the department of otolaryngology at Children’s Hospital Boston. “Five or six possibilities have come up, but didn’t pan out.”

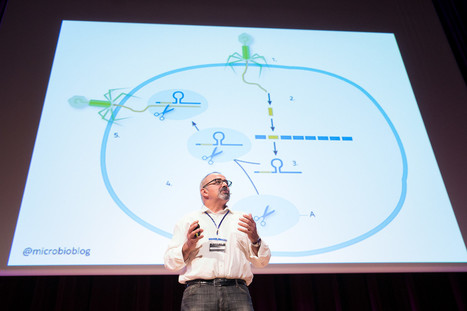

Recently, in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, team led by Holt and Andrew Griffith, of the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), demonstrated that two related proteins, TMC1 and TMC2, are essential for normal hearing – paving the way for a test of gene therapy to reverse a type of genetic deafness.

The two proteins make up gateways known as ion channels, which sit atop the hair-like structures (a.k.a. stereocilia) and let electrically charged molecules move in to the cell, generating an electrical signal that ultimately travels to the brain. When both the TMC1 and the TMC2 genes are mutated, sound waves can’t be converted to electrical signals – they literally fall on deaf ears.

Via

Dr. Stefan Gruenwald

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...