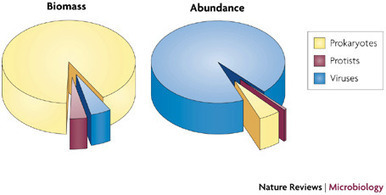

Viruses are by far the most abundant 'lifeforms' in the oceans and are the reservoir of most of the genetic diversity in the sea. The estimated 10^30 viruses in the ocean, if stretched end to end, would span farther than the nearest 60 galaxies. Every second, approximately 10^23 viral infections occur in the ocean. These infections are a major source of mortality, and cause disease in a range of organisms, from shrimp to whales.

As a result, viruses influence the composition of marine communities and are a major force behind biogeochemical cycles. Each infection has the potential to introduce new genetic information into an organism or progeny virus, thereby driving the evolution of both host and viral assemblages. Probing this vast reservoir of genetic and biological diversity continues to yield exciting discoveries.

Viruses can be found in every environment on the Earth, but their importance is perhaps most evident in the oceans, where they are known to be the reservoir of most of the genetic diversity. Viruses kill approximately 20% of the oceanic microbial biomass daily, which has a significant impact on nutrient and energy cycles. This Review highlights areas in which marine virology is advancing quickly or seems to be poised for paradigm-shifting discoveries.

Developing the necessary techniques to obtain accurate and reproducible estimates of the distribution and abundance of marine viruses has been a challenge for researchers. Sub-populations of both viruses and host cells can now be discriminated using flow cytometry. Viral abundance generally co-varies with prokaryotic abundance and productivity, but marked differences in this relationship have been reported in different marine environments.

Quantifying the effects of viruses on marine prokaryotic and eukaryotic heterotrophic and autotrophic communities is also a challenging area, and remains one of the biggest obstacles to incorporating viral-mediated processes into global models of nutrient and energy cycling.

Our knowledge of the diversity of viruses in marine environments has increased greatly with the development of metagenomic approaches. The interactions between viruses and the organisms they infect ultimately control the genetic diversity of viruses and potentially influence the composition of microbial communities. However, the experimental evidence that supports the hypothesis that viruses regulate microbial diversity in nature is ambiguous. This is perhaps not surprising as the effects of viruses on their host cells depend on transient associations, which might lead us to expect that the influences of viruses on host populations will also be spatially and temporally variable.

Viruses/bacteria video collection: http://tinyurl.com/7plkwe3

Your new post is loading...

Your new post is loading...